Lead Author: Fan Jiao

Contributing Authors: Xin Su, Phil Tajitsu Nash, Jianping Xu

Editors: Pingbo Zhou, Steven Chen, Ji Su

Summary of Proposal for National Museum of AAPI

We are the “Friends of the National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (Friends of the National AAPI Museum)”, and we are about to start conversations on the establishment of a National Museum of Asian American and Pacific Islander History and Culture (NMAAPIHC) with all communities.

When the Smithsonian Institution held the 44th annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in June 2010 to celebrate the AAPI community, which consists of approximately 30 Asian American and 24 Pacific Islander American groups in the United States, the more than 350,000 AAPIs who live in the DC area and many more online represented a microcosm of cultural and history diversity.

Recently, national museums have been developing visions to be reflective of broader racial and ethnic communities and to engage with more diverse audiences, including minority groups such as African American and Hispanic communities. As a result, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) was created in 2016 and has been a success with 3.6 million visitors since its opening. The legislation for establishing the National Museum of the American Latino was passed into law early this year, and the museum is about to be constructed.

On May 25, 2021, Congresswoman Grace Meng (D-NY-6) introduced bill H.R. 3525 – Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Museum of Asian Pacific American History and Culture Act (117th Congress), calling on the Smithsonian to consider opening a National Museum of Asian Pacific American History and Culture. This bill followed several bills previously proposed by Meng since December 18, 2015.

“We need to weave the narrative of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities into the greater American story,” said Meng in one legislative session. “I firmly believe the story of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders is sorely misunderstood and creating a national museum would ensure that our experiences—both good and bad—are recognized by all Americans.”

“Museums are gateways for Americans and the world to see the United States’ rich history, challenges it overcame, and potential for greatness. Establishing this commission is the first step toward the creation of a national AAPI museum. I urge my colleagues to support this legislation.”

Given rising racial and ethnic diversity with Asians & Pacific Islanders as the fastest-growing racial group, our strong support of local AAPI museums, and the AAPI’s love for their own heritage and culture, we respectfully request that Congress pass legislation related to the National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to start working with the Smithsonian Institution, in partnership with the private sector, to build a National Museum of Asian American and Pacific Islander History and Culture (NMAAPIHC) that is comparable to the Smithsonian museums rightly celebrating Americans with roots in Africa and Latin America. Using the last remaining lot on the National Mall, the U.S. Congress together with the Smithsonian will send a strong message that AAPIs belong, and are a welcome part of the multi-racial, multicultural American family; their stories are America’s stories and this museum is for all Americans.

This document contains

- Proposal for National Museum of Asian American and Pacific Islanders History and Culture

- Calls for Action

- A Brief Glimpse of AAPI

- Appendices

- Appendix A. Relevant House Bills

- Appendix B. Current Status of Local AAPI Museums

Proposal for National Museum of AAPI History and Culture

The National Museum of Asian American and Pacific Islander Museum will display American history and culture through the lens of AAPIs, but people of all backgrounds will be able to make meaningful connections with this history, while reflecting on the “more perfect union” that each of us is striving to build on these shores.

The National Museum of Asian American and Pacific Islander History and Culture (NMAAPIHC) will stand on the following four cornerstones:

- It provides an opportunity for people to explore and reveal the history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs), as an essential part of American history and learn their history & culture, successes, barriers and fought back through interactive exhibits and online presence.

- It explores what it means to be an American and shares how American values like diligence, emphasis on education, family responsibility, optimism, resiliency, and spirituality are reflected in AAPI history, culture, and contribution to American history.

- It provides all Americans an AAPI perspective through which to view their stories, their histories, and their cultures and shows how they have been shaped and informed by global influences, especially in this museum, by the successes and impact of AAPIs.

- It serves as a center of collaboration that reaches beyond Washington, D.C. to engage new audiences and to work with all local AAPI history and culture museums and educational institutions well before this museum is created.

As one of twenty libraries in the Smithsonian Libraries system, the NMAAPIHC Library will be devoted to collecting and providing access to resources that support research in AAPI history and culture, as well as the Asian & Pacific Islander Diaspora including topics in the arts, humanities, and social sciences.

The library also would support research in genealogy and family history.

The library’s primary mission is to provide support for the research, exhibition, and programmatic endeavors of the NMAAPIHC. It accomplishes this by collecting, preserving, and providing access to resources and scholarship in the subjects of AAPI history and culture. The broader mission is to assist in supporting the scholarly needs of the Smithsonian Institution as a whole, as well as the independent research community who will also utilize the library’s resources and services.

The collection will include books, journals, and electronic resources. The library will also collect media and microfilm in modest amounts.

English is the prevailing language collected by the library; however, other languages that dominate in the AAPI diaspora such as Vietnamese, Urdu, Thai, Tagalog, Malay, Lao, Korean, Khmer, Japanese, Indonesian, Hindi, Chinese, and Burmese may also be collected on a limited basis.

Shown below is the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), with some fun facts that is an excellent example of how we envision the National Museum of Asia American and Pacific Islander History and Culture (NMAAPIHC) to be.

- H.R.5305 National African-American Heritage Museum and Memorial Act – 100th Congress (1987-1988), was proposed by Rep. John Lewis.

- S.1959 National African-American Heritage Memorial Museum Act – 101st Congress (1989-1990), was proposed by Sen. Paul Simon.

- President George W. Bush signed legislation for the museum in 2003.

- The current site was selected in 2006, and groundbreaking on the 5-acre site took place in February 2012.

- The museum was opened on Sept. 24, 2016, in a ceremony led by President Barack Obama, and George W. Bush.

- The building’s total cost of construction and exhibition installations was $540 million. This total was funded by both federal, the Smithsonian, and private funds.

- The museum has about 85,000 square feet of exhibition space with 12 exhibitions, 13 different interactives with 17 stations, and 183 videos housed on five floors.

- The admission for the museum is free.

- 3.5 million visitors since the opening day

- About 100,000 people joined the museum as members.

- 613,308 social media fans

- 5 million interactions per month

- 60,000 mobile app downloaded

- 50,000 active users

Calls for Action

Without improved education and awareness of the role AAPIs have played in America’s history, the prevalent negative impacts of stereotypes and discrimanation towards AAPI communities will continue to pervade our society, and contributions from AAPIs will continue to be largely ignored in K-12 history curriculums and public awareness. The lack of societal knowledge about AAPI communities also makes people unaware of the differences and inequalities among AAPI communities themselves, which often differ significantly in terms of income and educational attainment, among other factors. It is the time for society to correct its negative perceptions towards AAPIs and acknowledge the contributions that AAPI communities have made to the United States. This is the first step to allowing AAPIs to reclaim their true identity in this nation.

A nation-wide AAPI museum like NMAAPIHC will enable generations of all Americans to honor the history, accomplishments, and culture of AAPI Americans, understand that AAPI communities have contributed to this country just as much as any other ethnic groups, and recognize that the history of AAPIs is a vital part of American history and achievement. People of all backgrounds should be able to see American history through a variety of perspectives in order to help them reflect on their own experiences and make meaningful connections between themselves and others by developing a more well-rounded understanding of other cultures. The museum would also provide them a powerful tool to understand and prevent prejudice, discrimination, and hate.

All my fellow Americans, please support this important cause in whichever way you can, including but not limited to the following:

- Spread the word around your community to become Friends of the Museum

- Continue helping and / or visiting your local AAPI museums

- Ask your Congresswoman / Congressman to co-sponsor Congresswoman Meng’s bills

- Ask your Senators to issue Senate bills for the National Museum of AAPI History and Culture

Friends of the National APPI Museum

Email address: friendsofaapim@gmail.com

A Brief Glimpse of AAPI

What You Will See at the National AAPI Museum

This brief overview of AAPI history is to show where we AAPIs come from, the successes we have enjoyed and the barriers we have faced, and the struggles we have endured to overcome those barriers. The AAPI Museum will provide details of the histories mentioned here and many more. However, by thematically focusing on successes and barriers, Americans of all backgrounds will be inspired to preserve the best of their own histories and to build a world of justice, peace, and understanding for all people in the future.

1. Coming to America

It is important for the AAPI Museum to show where and how the first generation of AAPI immigrants got to the U.S. initially to help AAPI learn about the hardships overcome, and the successes achieved by past generations.

Chinese, then Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Indian immigrants came to the West Coast to work to build America in the 1800s. The Chinese were first banned by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Later, the Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited virtually ALL Asians from entering the United States.

1.1 Chinese Immigrants

Beginning in the 1850s when young single men were recruited as contract laborers from Southern China, Asian immigrants have played a vital role in the development of this country. Working as miners, railroad builders, farmers, factory workers, and fishermen, the Chinese represented 20% of California’s labor force by 1870, even though they constituted less than 0.2% of the entire United States population. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act—the only United States Law to prevent immigration and naturalization on the basis of race—which restricted Chinese immigration for the next sixty years. The “Chinese Must Go” movement was so strong that Chinese immigration to the United States declined from 39,500 in 1882 to only 10 in 1887. The subsequent Immigration Act of 1924 effectively banned all immigration from Asiaand set a total immigration quota of 165,000 for countries outside the Western Hemisphere,

With the outbreak of WWII causing the United States and China to fight together as allies against Japan, Congress passed a measure in 1943 to repeal the discriminatory exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants. Since then, more and more Chinese immigrants have come to the U.S. to work and study, especially since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the People’s Republic of China in 1979.

According to the 2020 census, there were 5.4 million Chinese Americans. The states with the top five largest estimated Chinese American populations, were California, New York, Texas, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. The State of Hawaii has the highest concentration of Chinese Americans at 4.0%, or 55,000 people.

1.2 Filipino Immigrants

In the final years of the 19th century, the U.S. went to war with Spain, ultimately annexing the Philippine Islands from Spain. As the result, the history of the Philippines merged with that of the U.S., beginning with the three-year-long Philippine–American War (1899-1902), which resulted in the defeat of the First Philippine Republic.

By 1924, because of the Barred Zone Act, all Asian immigrants with the exception of Filipino “nationals”, including Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and Indians were fully excluded by law, denied citizenship and naturalization, and prevented from marrying Caucasians or owning land.

Thousands of young, single Filipino men began migrating in large numbers to the West Coast during the 1920s to work in farms and canneries, filling the continual need for cheap labor. However, racism and economic competition, intensified by the depression of 1929, led to severe anti-Filipino violence and passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1935, which placed an annual quota of fifty on Filipino migration—effectively excluding their entry as well.

As of 2020, there were 4.2 million Filipinos, or Americans with Filipino ancestry, in the United States with large communities in California, Hawaii, Illinois, Texas, and the New York metropolitan area.

1.3 Japanese Immigrants

By 1885, following the Chinese Exclusion Act, large numbers of young Japanese laborers, together with smaller numbers of Koreans and Indians, began arriving on the West Coast where they replaced the Chinese as cheap labor in building railroads, farming, and fishing. Anti-Japanese agitation soon took hold, especially in California, where the state government routinely petitioned Congress for wholesale Japanese exclusion.Despite a short period of goodwill after Japan gave San Francisco a substantial donation to recover from a massive earthquake, anti-Japanese policies soon re-emerged.In the fall of 1906, the San Francisco board of education announced that all Japanese children would attend segregated schools.Growing anti-Japanese legislation and violence soon followed. In 1907, Japanese immigration was restricted by the “Gentleman’s Agreement” between the United States and Japan.

According to the 2020 census, Japanese Americans constitute the sixth largest Asian American group at around 1.5 million, including those of partial ancestry.

1.4 Korean Immigrants

Small numbers of Korean immigrants came to Hawaii and then the mainland United States following the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War and Japan’s occupation of Korea. Serving as strike-breakers, railroad builders, and agricultural workers, Korean immigrants faced not only racist exclusion in the United States but Japanese colonization at home.

Taking refuge from Japanese imperialism and growing poverty and famine in Korea, and encouraged by Christian missionaries, thousands of Koreans migrated to Hawaii in the early 1900s. Some Korean patriots also settled in the United States as political exiles and organized for Korean independence.

According to the 2020 Census, there were approximately 1.9 million people of Korean descent residing in the United States, making it the country with the second-largest Korean population living outside Korea (after the People’s Republic of China). The five states with the largest estimated Korean American populations were California, New York, New Jersey, Virginia, and Texas. Hawaii was the state with the highest concentration of Korean Americans, at 1.8%, or 23,200 people.

1.5 South Asian Indian Immigrants

Recruited initially by Canadian-Pacific railroad companies, a few thousand Sikh immigrants from the Punjabi region immigrated to Canada which, like India, was part of the British empire. Later, many migrated to the Pacific Northwest and California and became farm laborers. Ironically decried as a “Hindu invasion” by exclusionists and Caucasian labor, the “tide of the Turbans” was outlawed in 1917 when Congress declared that India was part of the Pacific-Barred Zone of excluded Asian countries to prohibit the entry of migrants from India.

While the Luce-Celler Act of 1946 established a yearly quota of 100 Indian immigrants, it was the Immigration and Nationality Act 1965 that removed national-origin quotas altogether, paving the way for non-European arrivals. From 1980 to 2019, the Indian immigrant population in the United States increased 13-fold.

With a population of 4.6 millions in 2020, Indian Americans make up 1.2% of the U.S. population and are the largest group of South Asian Americans and the second largest groupof Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders after Chinese Americans. The New York metropolitan area comprises the largest population of Indian Americans among U.S. metropolitan areas.

1.6 Southeast Asian Immigrants

The majority of Southeast Asian Americans share a common immigration history, which is the legacy of U.S. involvement in the Indochina Conflict (1954–1975), also known as the Vietnam War. Beginning in 1975, Southeast Asian refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos have entered the United States after escaping from war, social chaos, discrimination, and economic hardship. Roughly one million Southeast Asians, including about 30,000 Amerasian children of American servicemen and their families, have entered the United States since then through a variety of refugee resettlement and immigration programs.

Refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos each have distinct cultures, languages, and contexts of historical development. Although each country shares certain influences from their common history as French colonial territories for nearly a century until 1954, Vietnam is much more culturally influenced by China while Cambodia and Laos have been more influenced by India. Within each country, there are Chinese and other ethnic minority populations such as the Hmong, Mien, and Khmer from Laos.

The 2020 Census enumerates 1.2 million Vietnamese; 169,428 Hmong; 168,707 Lao; 171,937 Cambodian; and 112,989 Thai Americans living in the United States (refer to Southeast Asian Americans).

2. AAPI Successes

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have contributed to this country in many ways, including Nobel Prizes, building the transcontinental railroad, serving in the military, contributing to science and technology, social sciences, architecture and design, fashion, sports, entertainment, music, writing, and business.

2.1 AAPI Nobel Laureates

Given that AAPIs have always been a small fraction of the United States population, they have made outsized contributions to knowledge and brought tremendous honor to this country through the following Nobel Prize awards:

- Abhijit Banerjee (2019 Economics): Indian American who developed experimental approach to alleviating global poverty

- Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (1983 Physics): Indian American who worked on the physical processes important to the structure and evolution of stars

- Steven Chu (1997 Physics): Chinese American who developed methods to cool and trap atoms with laser light

- Charles K. Kao (2009 Chemistry): Chinese American who made groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibers for optical communication

- Shuji Nakamura (2014 Physics): Japanese American inventor of efficient blue light-emitting diodes, which enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources

- Yoichiro Nambu (2008 Physics): Japanese American who discovered (in 1960) the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in subatomic physics

- Yang Chen-Ning (1957 Physics): Chinese American who investigated so-called parity laws, which has led to important discoveries regarding elementary particles

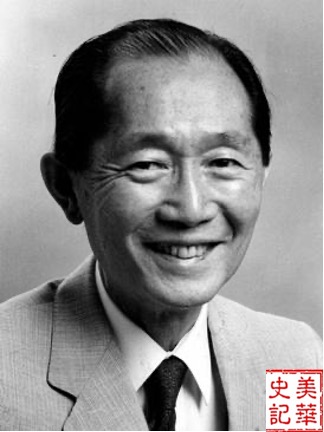

- Tsung-Dao Lee (1957 Physics): Chinese American who worked on the violation of the parity law in weak interactions, which Chien-Shiung Wu experimentally proved from 1956 to 1957, with her legendary Wu experiment.

- Har Gobind Khorana (1968 Physiology/Medicine): Indian American who showed the order of nucleotides in nucleic acids

- Yuan T. Lee (1986 Chemistry): Taiwanese American who made contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes

- Charles J. Pedersen (1987 Chemistry): Korean American discoverer of crown of ethers

- Venki Ramakrishnan (2009 Chemistry): Indian American who studied the structure and function of the ribosome

- Aziz Sancar (2015 Chemistry): Turkish American who performed mechanistic studies of DNA repair

- Samuel C. C. Ting (1946 Physics): Taiwanese American who did pioneering work in the discovery of a heavy elementary particle of a new kind

- Roger Y. Tsien (2008 Chemistry): Chinese American who discovered and developed the green fluorescent protein GFP

- Daniel C. Tsui (1998 Physics): Chinese American who discovered a new form of quantum fluid with fractionally charged excitations

2.2 Building the Transcontinental Railroad

On May 10, 1869, Leland Stanford tapped the ceremonial Gold Spike into a pre-drilled hole to link the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, creating the First Transcontinental Railroad. The first Transcontinental Railroad in America was built from 1865 to 1869, which connected the east and west coasts of the American Continent for the first time in history. Chinese railroad workers played an integral role in the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad (SeeHistorical Record of Chinese Americans | Following the Footprint of Transcontinental Railroad Builders by Zhida Song-James).

As early as 1858, Chinese workers had begun to build railways in California. According to a report by the Sacramento Union, the California Central Railroad once hired fifty Chinese workers to build the Sacramento-Marysville railway. It didn’t take long for their reputation of hard work, perseverance, and reliability to spread in the engineering world. By the time the railway climbed along the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada to Colfax in the fall of 1865, the number of Chinese workers had increased to more than 3,000. When no more Chinese workers could be hired in California, the Central Pacific Railway Company turned to Chinese labor intermediaries and directly advertised to recruit laborers out of China. Among 15,000 workers who worked on constructing the most dangerous segment of this railroad, more than 13,000 were Chinese.

Some Chinese workers continued to build railways in the western states. The Southern Pacific Railway Company hired a group of Chinese workers to extend the northern California railroad to southern California, which brought rapid development and prosperity in the 1880s for southern California. In 1870, the Northern Pacific Railroad established a base where is now Kalama, Washington. It planned to build a railroad from there northward to connect to the Northern Pacific Railroad, which was advancing westward from Minnesota. The project managers recruited a large number of Chinese workers. Kalama even had a Chinatown called China Garden. The Chinese workers had left their footprint in the Montana portion of the Northern Pacific Railway, the Alabama and Chattanooga Railway from Alabama to Tennessee, and the Houston and Texas Railway from the Lone Star state.

On April 29, 1999, Congressman John T. Doolittle (R, CA-4) thanked “the entire Chinese-American community for its ancestors’ contribution to the building of this great Nation” in the House of Representatives (See CREC-1999-04-29-pt1-PgE822-4.pdf)

2.3 Military Services

Civil War

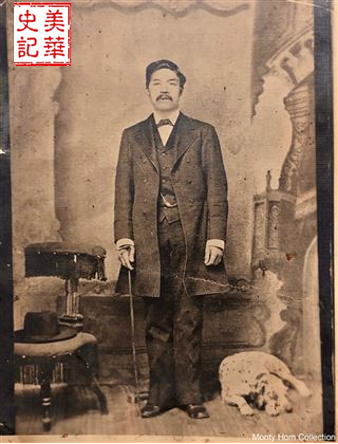

AAPI immigrants have always been heroic fighters/protectors for their adopted country (see Since the Civil War, Asian Americans have served in the military with distinction ).

Edward Day Cohota was born in Shanghai, China, and was “adopted” by the captain of the merchant ship Cohota, Sargent S. Day. He served in the 23rd Massachusetts Infantry during the American Civil War.

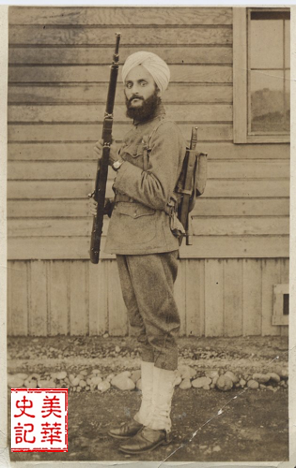

During WWI, Indian American Bhagat Singh Thind, who served in the U.S. Army, was promoted to sergeant. He was the first U.S. serviceman to be allowed for religious reasons to wear a turban as part of their military uniform.

The U.S. Navy’s Arctic Expedition

Human explorers to the Arctic have long considered it an extraordinary journey of courage and endurance. In the 20-year period between 1860 to 1880, an Arctic expedition set off virtually every year. Charles Tong Sing and Ah Sam were part of the 1879 U.S. Navy Arctic Expedition on the USS Jeanette. In December 1892, Tong Sing formally received his medal. For the details of the Expedition please see Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The First Chinese Americans In The Arctic: Charles Tong Sing And Ah Sam by Qian Huang.

Lau Sing Kee (1896-1967) served in 77th Division of the U.S. Army, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the French Croix de Guerre. He served in the 77th Division of the U.S. Expeditionary Force, No. 306 Infantry Regiment, and G Company. He was the first Chinese American to be decorated for bravery. To see how Lau Sing Kee had been immortalized by Stevie Wonder in his song “Black Man” please refer to Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Lau Sing Kee, Chinese-American Hero Of The First World War by Qian Huang.

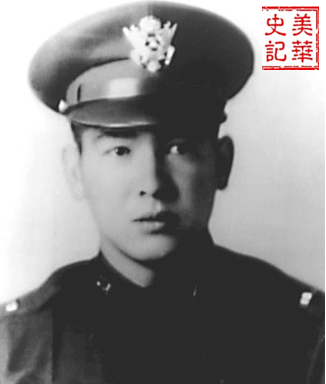

In WWII, the 442nd Regiment composed almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) was the most decorated unit for its size in U.S. military history, activated on February 1, 1943. The unit quickly grew to its fighting complement of 4,000 men by April 1943, and an eventual number of about 14,000 men served in total. The unit, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, earned more than 18,000 awards in less than two years, including more than 4,000 Purple Hearts and 4,000 Bronze Star Medals.

At that time, there were 78,000 native Chinese in the mainland of the United States and another 29,000 living in Hawaii, for a total of 107,000 Chinese in the U.S. Among them, 20,000 young men and women signed up for the U.S. military, accounting for one-fifth of the total number of Chinese. These Chinese soldiers were assigned to various branches of the U.S. military. About 25% of Chinese soldiers served in the Air Force and were sent to the China-Myanmar-India theater (Historical Record of Chinese Americans |The Chinese American “Flying Tigers” In World War II by Ann Lee). Another 70 percent went on to serve in the U.S. Army in various units, including the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 32nd and 77th Infantry Divisions (Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Honoring the Chinese American Veterans of WWII by Annette Chan). Chinese American women were accepted into the Women’s Army Corps in the Military Intelligence Service. They were also recruited for service in the Army Air Force, Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Chinese American Servicewomen In World War II by William Tang.

Among many Chinese WWII heroes, Francis Brown Wai (April 14, 1917 – October 20, 1944) was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for extraordinary heroism in action in Leyte, Philippines. He was a United States Army captain who was killed in action during the U.S. assault and liberation of the Philippine Islands from Japan in 1944, during WWII.

In April 1942, Filipinos together with some Chinese Filipinos were on the front line fighting against Japanese invaders in Philipin, and suffered some great losses (among them was Brigadier General Vicente Lim). In the U.S., many enlisted Filipino soldiers were subjected to discrimination during their time training at Camp Beale and Fort Ord, sometimes being mistaken for Japanese Americans when off base. By the end of the war, a total of 50,000 decorations, awards, medals, ribbons, certificates, commendations and citations had been awarded to personnel assigned to these two Filipino regiments for their service in the New Guinea and Philippines campaigns.

U.S. Army Brigadier General Vicente Lim, was the first Filipino graduate from West Point, and Filipino American officer who served under Generals Douglas MacArthur and Jonathan Wainwright in the Philippines during WWII. During the Battle of Bataan, Lim was the Commanding General of the 41st Infantry Division, Philippine Army. He was executed in late 1944 after being captured.

By the time Japan annexed Korea in 1910, many Koreans had been fighting Japanese rule for decades. As a result, about a few hundred Korean Americans enlisted in the U.S. over the course of the war. Some of them joined the 442nd Regiment, and a few of them became fighter aces or warship gunners.

Ahn family portrait: Korean Americans who served in WWII

In 2018, as a result of Congress passing and the President signing Public Law 115-337, the Congressional Gold Medal, our nation’s highest honor, was presented to these individuals of Chinese ancestry who served honorably at any time during the period December 7, 1941, and ending December 31, 1946.

Korean War

Of the 36,572 Americans who died during the Korean War, 241 were Asian Americans.

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, 35,000 Asian Americans served as part of the more than eight million U.S. service personnel that were deployed to South Vietnam, in fully integrated units, including Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Laotians, and Vietnamese Americans.

By 1989, Asian Americans made up approximately 2.3 percent of the total armed services, slightly greater than their proportion of the total U.S. population at that time (1.6 percent).

Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Wars

During the Persian Gulf War, many Asian Americans served in the U.S. military, with some filling senior officer positions, including Major General John Fugh who was promoted to the position of Army Judge Advocate General during the conflict.

As of April 2017, out of the 2,346 deaths that have occurred in Operation Enduring Freedom, 62 have been Asian Americans (47 Soldiers, 8 Marines, 6 Sailors, and 1 Airman).As of September 2018, an additional 390 Asian American service-members have been wounded (307 Soldiers, 58 Marines, 18 Sailors, and 7 Airmen).

Asian American Marines were part of the first conventional units to enter into Afghanistan in late 2001, including Pakistani American marine Lieutenant Colonel Asad A. Khan.Khan would return to Afghanistan in command of 1st Battalion 6th Marines in 2004.

Hundreds of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have deployed to Iraq out of the 59,000 plus that were serving in active duty as of May 2009.

In recent years, Asian Americans & Pacific Islanders have been represented well at the military academies compared to their share of the national population. Although Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are 3.49% of the national population aged 18–24,they are about 9–10% of the classes of 2014 at West Point,the Naval Academy, and the Air Force Academy. For a story of 3-generation Chinese American servicemen/women family, please refer to Historical Record of Chinese Americans | From Transcontinental Railroad Worker, Wwii Hero, Major General, To Black Hawk Pilot – The Contributions From A Four-generation Chinese American Family by Fan Jiao).

2.4 Political Trailblazers

Led by the Vice President Kamala Harris, the first African and Asian American vice president of the U.S, currently there are some outstanding APPI congress persons including Senators Tammy Duckworth, Mazie Hirono, Representatives Judy Chu, Ro Khanna, Andy Kim, Young Kim, Grace Meng and Bobby Scott. Here are some political pioneers of our very own:

- Dalip Singh Saund (1899 – 1973) was the first Indian American, and first Sikh American Congressman from California. In 1930, he wrote a book called “My Mother India” addressing India’s caste system as one of those questions and pleaded for the civil rights of the downtrodden in India as he compared caste in India to racism in America.

- S. I. Hayakawa (1906 – 1992) was a Canadian-born American academic and politician of Japanese ancestry. A professor of English, he served as president of San Francisco State University and then as a Republican Senator from California from 1977 to 1983. In 1978 he helped win Senate approval of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, which transferred control of the zone and canal to Panama.He also supported a bill that led to the creation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which examined the causes and effects of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII.

- Hiram Fong (1906 – 2004) was a Chinese American Senator from Hawaii serving as a Major in the United States Army Air Forces during WWII. From 1948 to 1954, he was one of the foremost leaders in making Hawaii a state. He voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960, 1964, and 1968,as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- Spark Matsunaga (1916 – 1990) was a Japanese American Congressman and Senator from Hawaii. He served the renowned 442nd Regiment as a Captain in WWII. He was instrumental in the passage of a reparation bill for people of Japanese descent who were incarcerated in the United States during the war.

- Daniel Inouye (1924 – 2012) was a Japanese American Congressman and Senator from Hawaii who served in 442nd Regiment. He lost his right arm and once was wounded 5 times in a day in WWII. In 1984 he introduced the National Museum of the American Indian Act which led to the inauguration of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. In 2000, President Clinton presented the Medal of Honor to the Senator.

- Daniel Akaka (1924 – 2018) was a Hawaiian/Chinese American Congressman and Senator from Hawaii after serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in WWII. During his Senate tenure, he served as the Chair of the United States Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and the United States Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. In 1996, he successfully sponsored legislation that led to nearly two-dozen Medals of Honor being belatedly awarded to Asian American soldiers in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion. He also successfully passed legislation compensating Philippine Scouts who were refused veterans benefits in WWII.

- Patsy Mink (1927 – 2002) was the first woman of color, the first Asian and Japanese American woman elected to Congress. In the late 1960s, she introduced the first comprehensive initiatives under the Early Childhood Education Act, which included the first federal child care bill and bills establishing bilingual education, Head Start, school lunch programs, and special education. She also co-authored and advocated for the passage of Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act, prohibiting gender discrimination in federally funded institutions. She was also the first Asian American woman to run for president entering the race in 1971 to become the Democratic Party’s nominee.

2.5. Science and Technology

Aside from the Nobel Laureates mentioned above, AAPIs have been pioneers in many aspects of science and technology for many decades.

Astronauts

Lieutenant Jonny Kim was a U.S. Navy SEAL who completed more than 100 combat operations and is the recipient of the Silver Star and Bronze Star with Combat “V”. Dr. Kim was commissioned as a naval officer through an enlisted-to-officer program and earned his degree in mathematics at the University of San Diego and a MD at Harvard Medical School. In April 2021, Kim was selected to serve as the International Space Station’s Increment Lead for Expedition 65.

Colonel Ellison Shoji Onizuka (1946 – January 28, 1986) was a distinguished U.S. Air Force pilot before becoming part of NASA’s Astronaut Class of 1978. He became the first Asian American astronaut in space when he completed a mission on Space Shuttle Discovery in 1985. Unfortunately, his life was cut short in 1986 as part of the team aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger. He was the first Asian American and the first person of Japanese origin to reach space.

Engineering

Dr. Ajay V. Bhatt is an Indian-born American computer architect who defined and developed several widely used technologies, including USB and various chipset improvements.

Medical Research

Dr. David Da-i Ho is a Taiwanese American AIDS researcher, physician, and virologist who has made a number of scientific contributions to the understanding and treatment of HIV infection. Characteristically modest and quick to share credit with his associates, Dr. David Ho continues to lay forth clearly and succinctly some of the boldest yet most cogent hypotheses in the epic campaign against HIV.

Technology Education

Reshma Saujani (born November 18, 1975) is an American lawyer, civil servant, and the founder of the nonprofit organization Girls Who Code, which aims to increase the number of women in computer science and close the gender gap in that field. She worked in city government as a deputy public advocate at the New York City Public Advocate’s office. In 2009, Saujani ran against Carolyn Maloney for the U.S. House of Representativesseat from New York’s 14th congressional district, becoming the first Indian American woman to run for Congress in NY history.

Climatology

Dr. Tetsuya Theodore Fujita (October 23, 1920 – November 19, 1998) was a Japanese American meteorologist whose research primarily focused on severe weather. His research at the University of Chicago included work on severe thunderstorms, tornadoes, hurricanes, and typhoons. He was best known for creating the Fujita scale of tornado intensity and damage. He was also an instrumental figure in advancing modern understanding of many severe weather phenomena and how they affect people and communities, especially through his work exploring the relationship between wind speed and damage.

Internet Technology Leaders

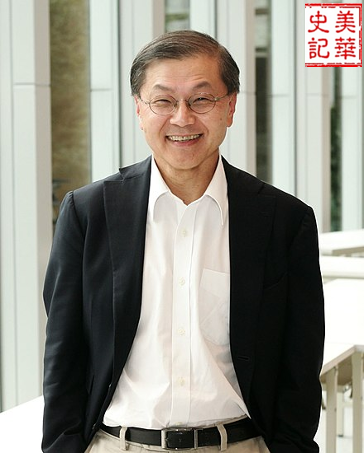

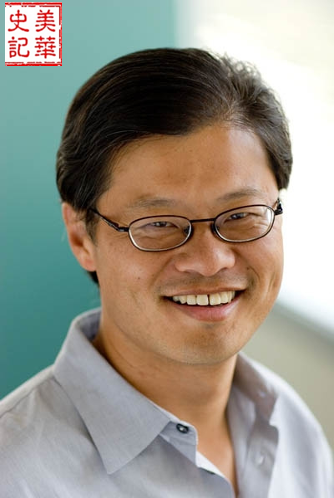

Jerry Chih-Yuan Yang (born November 6, 1968) is a Tainwaness American, internet entrepreneur, and venture capitalist. He is the co-founder and former CEO of Yahoo! Inc.

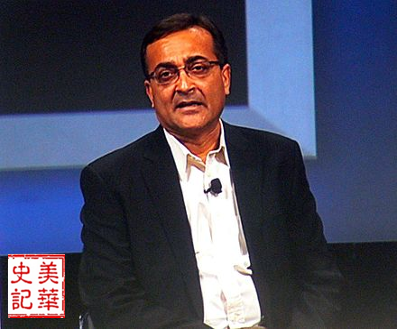

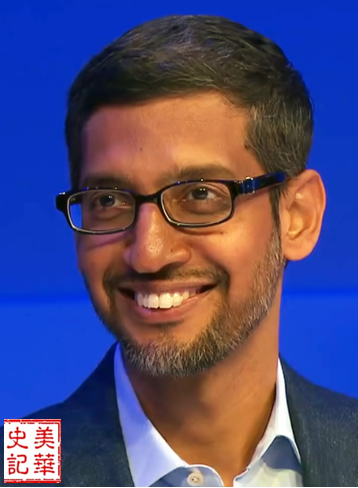

Pichai Sundararajan began his career as a materials engineer. He joined Google in 2004,where he led the product management and innovation efforts for a suite of Google’s client software products, including Google Chrome and Chrome OS.

Pichai was selected to become the next CEO of Google on August 10, 2015. On October 24, 2015, he stepped into the new position at the completion of the formation of Alphabet Inc., the new holding company for the Google company family. He was appointed to the Alphabet Board of Directors in 2017.

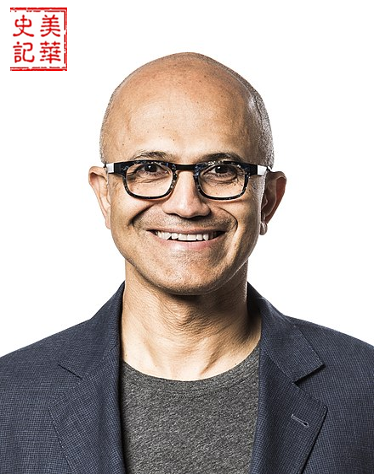

Satya Nadella worked at Sun Microsystems as a Member of Technical Staff before joining Microsoft in 1992. At Microsoft, Nadella has led major projects that included the company’s move to cloud computing and the development of one of the largest cloud infrastructures in the world.Nadella worked as the senior vice-president of R&D for the Online Services Division and vice-president of the Microsoft Business Division under the leadership of Lu Qi. On 4 February 2014, Nadella became the new CEO of Microsoft, the third CEO in the company’s history, following Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer.

Aside from those AAPI leaders, since the 1960s, Chinese immigrants have arrived in the Bay Area/Silicon Valley; many more have come from the mainland since the eighties. In the last four decades, many of them have become high tech entrepreneurs and engineers who have contributed a great deal to Silicon Valley and the U.S. economy (see Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Silicon Valley Chinese American Leaders by Fan Jiao).

Physics

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu (1912-1997) was an experimental physicist who was best known for her work on the Manhattan Project in WWII. Wu’s research focused on identifying a process to separate uranium metal through gaseous infusion, which was critical to transforming a dumb bomb into an atomic bomb. She was the only Chinese descendant to work in the war department and one of the few women among its senior researchers. She later helped two colleagues win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957 based on the Wu Experiment. Her awards include the National Medal of Science by President Ford in 1975 (see Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The Queen of Nuclear Research and TheChinese MadameCurie, Dr。 Chien-Shiung Wu by Fan Jiao).

2.6 Social Sciences

Dr. Wei-Jen Huang is a clinical psychologist and a faculty member at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. His mission in life is to serve the underserved Asians who are struggling with emotional pain but normally shy away from mental health services due to cultural stigma, financial difficulty, or the lack of trained Asian therapists in their communities. Dr. Huang was the 2004 United Nation International Family Conference Keynote Speaker, the 2014 Rotary International Assembly Keynote Speaker, and Plenary Speaker for the 2016 American Psychological Association Annual Convention. He was recognized as a national leader and invited to meet President George W. Bush at the White House.

Dr. Shefali Tsabary received her Ph.D in clinical psychology at Columbia. A New York Times best-selling author of Conscious Parenting and Oprah Winfrey’s favorite parenting expert, Shefali has been invited to speak and give presentations at prestigious institutions including Wisdom 2.0, TEDx, Kellogg Business School, and The Dalai Lama Center for Peace and Education.

2.7 Architecture and Design

Maya Yin Lin (born October 5, 1959) is an American designer and sculptor. In 1981, she achieved national recognition when she won a national design competition for the planned Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. while doing her undergraduate at Yale. As a second generation Chinese American, Maya has designed numerous memorials, public and private buildings, landscapes, and sculptures including the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. In 2016, Maya Lin was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC

I.M. Pei (26 April 1917 – 16 May 2019) was a Chinese American architect. He had been chief architect for many impressive buildings including the John F. Kennedy Library in Massachusetts and a glass-and-steel pyramid for the Louvre in Paris.

Pei won a wide variety of prizes and awards in the field of architecture, including the AIA Gold Medal in 1979, the first Praemium Imperiale for Architecture in 1989, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in 2003. In 1983, he won the Pritzker Prize, which is sometimes referred to as the Nobel Prize of architecture.

Louvre, Paris

Minoru Yamasaki (December 1, 1912 to Feb 6, 1986) was a second generation Japanese American, born in Seattle, Washington. He got a job with the architecture firm Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, designers of the Empire State Building. The firm helped Yamasaki avoid internment as a Japanese American during WWII, and he himself sheltered his parents in New York City. Among many buildings he created, the innovative design of the 1,360 ft (410 m) towers of the World Trade Center in 1964 was an architectural masterpiece, which began construction March 21, 1966. The first of the towers was finished in 1970.

Meejin Yoon is a Korean American educator, designer and architect who is the first woman to helm M.I.T. ‘s Department of Architecture. Currently, she is the Gale and Ira Drukier Dean at the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP) at Cornell and cofounder of Höweler + Yoon, an award-winning design studio engaged in projects across the U.S. and around the world.

Yoon’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, the Guggenheim Museum and the National Art Center in Tokyo.

The Collier Memorial, on MIT’s campus, honors Officer Sean Collier who was killed in April 2013. The memorial is composed of 32 blocks of granite that form a five-way stone vault.

2.8 Fashion

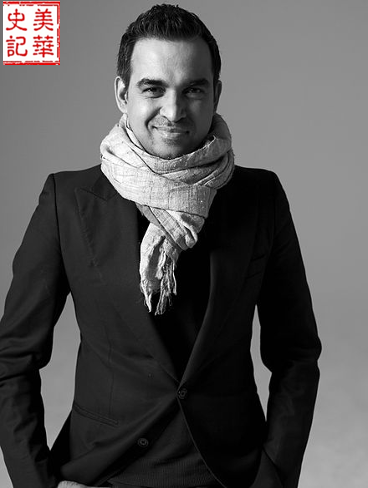

Phillip Lim (born September 16, 1973 as Pheng Lim) is an American fashion designer of Chinese descent whose parents immigrated to America from Thailand during the Cambodian genocide.

“3.1 Phillip Lim” is Lim’s fashion label. It was projected to have sales of $60 million in 2011. On September 15, 2013, Lim’s collaboration with retail chain Target debuted to select Target stores in the United States of America, and Canada.

Bibhu Mohapatra (born 7 June 1972 in Rourkela, Odisha, India) is a New York-based fashion and costume designer. In 2008 Mohapatra established his label, Bibhu Mohapatra -Purple Label. Since then, he has presented many collections of luxury women’s ready to wear, couture and fur under his name in New York, Mumbai, Frankfurt, Beijing, and New Delhi. His collections are sold by many boutiques around the world, including Bergdorf Goodman in New York, Neiman Marcus, SAKS, and Nordstrom in the United States, Lane Crawford in China, and other boutiques around the world.His creations have been featured in many fashion magazines including Time, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, and Vogue.

One of his most popular clients is the former First Lady Michelle Obama.

Vera Wang (born June 27, 1949) is an American fashion designer. Her parents were born in China and came to the United States in the mid-1940s.

Wang has made wedding gowns for public figures such as Hayley Williams, Ariana Grande, Chelsea Clinton, Karenna Gore, Ivanka Trump,Alicia Keys, Mariah Carey, and Victoria Beckham. Wang’s evening wear has also been worn by Michelle Obama.

She has designed costumes for figure skaters, including Nancy Kerrigan, Michelle Kwan, and Nathan Chen. Kerrigan wore a Wang piece for the 1992 and 1994 Winter Olympics, Kwan for the 1998 and 2002 Winter Olympics, and Chen for the 2018 Winter Olympics.Wang was inducted into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 2009 for her contribution to the sport as a costume designer.

Forbes placed her the 34th in the list America’s Richest Self-Made Women 2018, her revenues rising to $630 million in that year.

2.9 Sports

Michael Chang (born February 22, 1972) is an American businessman and retired professional tennis player. He is the youngest male player in history to win a Grand Slam tournament, winning the 1989 French Open at 17 years old. Chang won a total of 34 top-level professional singles titles, and reached a career-best ranking of world No. 2 in 1996.

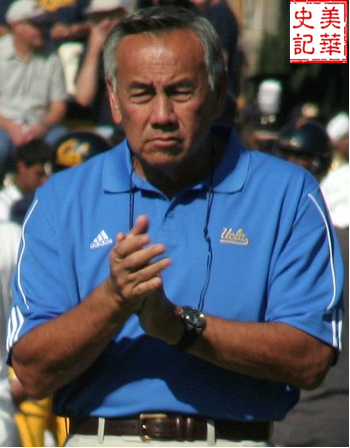

Norman Chow (born May 3, 1946) is an American football coach and former player. He was most recently the offensive coordinator for the Los Angeles Wildcats of the XFL. He was the head football coach at the University of Hawaii at Manoa (2011-2015) and previously held the offensive coordinator position for various division I schools including the UCLA Bruins, USC Trojans, NC State Wolfpack, and BYU Cougars, as well as the NFL‘s Tennessee Titans.

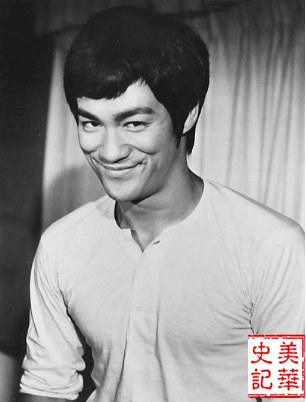

Bruce Lee (November 27, 1940 – July 20, 1973), was a Hong Kong American martial artist, actor, and director. Having initially learnt Wing Chun, tai chi, boxing, and street fighting, he combined them with other influences from various sources into the spirit of his personal martial arts philosophy, which he dubbed Jeet Kune Do (The Way of the Intercepting Fist). Over time, he has become an iconic figure known throughout the world, especially among the Chinese community for his portrayal of Chinese nationalism in his films. He is also renowned among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders for defying stereotypes associated with the emasculated Asian male.

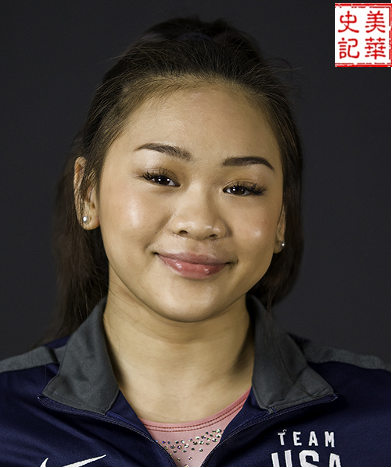

Sunisa “Suni” Lee (born March 9, 2003) is an American artistic gymnast. Lee is of Hmong descent, and her mother, a refugee, immigrated to the United States from Laos as a child. She is the 2020 Olympic all-around champion and uneven bars bronze medalist.

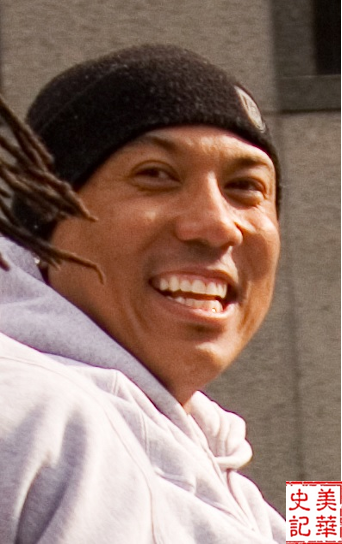

Apolo Ohno was born in Seattle, Washington on May 22, 1982, to a Japanese-born father, Yuki Ohno. Apolo is an American retired short track speed skating competitor and an eight-time medalist (two gold, two silver, four bronze) in the Olympics. Apolo is the most decorated American Olympian at the Winter Olympics and was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 2019.

Hines Edward Ward Jr. (born March 8, 1976) is born in Seoul, South Korea, to a Korean mother and African American father. Hines grew up in the Atlanta area. He has become an advocate for the social acceptance of foreigners in Korea, especially blended or mixed race youth.

He played college football at the University of Georgia and was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in the third round of the 1998 NFL Draft. Hines played his entire professional career for the Steelers and became the team’s all-time leader in receptions, receiving yardage and touchdown receptions. Hines Ward was voted MVP of Super Bowl XL and upon retirement was one of eleven NFL players to have at least 1,000 career receptions.

Eldrick Tont “Tiger” Woods was born December 30, 1975 Earl and Kultida Woods. Kultida is originally from Thailand, of mixed Thai, Chinese, and Dutch ancestry. Tiger is tied for first in PGA Tour wins, ranks second in men’s major championships, and holds numerous golf records.

Kristine Tsuya Yamaguchi (born July 12, 1971) is an American former figure skater, the 1992 Olympic champion, a two-time World champion (1991 and 1992), and the 1992 U.S. champion. In 1992, she became the first Asian American woman to win a gold medal in a Winter Olympic competition. Yamaguchi is Sansei (a third generation descendant of Japanese emigrants).

2.10 Entertainment

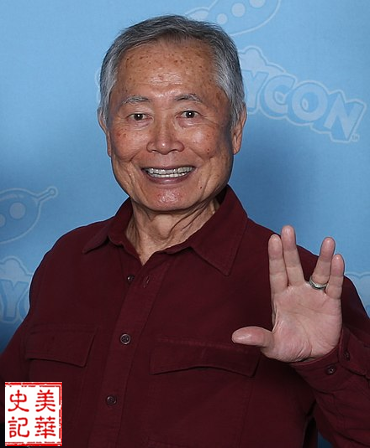

Actor George Takei (born in 1937) is a Japanese American and internationally known for his role as Hikaru Sulu, helmsman of the fictional starship USS Enterprise in the television series Star Trek and subsequent films. He is openly gay.

Margaret Cho (born in 1968) is a Korean American actress, musician, stand-up comedian, fashion designer, and author. She rose to prominence after creating and starring in the ABC sitcom All-American Girl(1994–95), and has become an established stand-up comic.

Mindy Kaling (born in 1979) is a second generation Indian American actress, comedian, writer, producer and director. She has been producer and director of The Office, The Mindy Project, The 40-Year-Old Virgin, and Ocean’s 8.

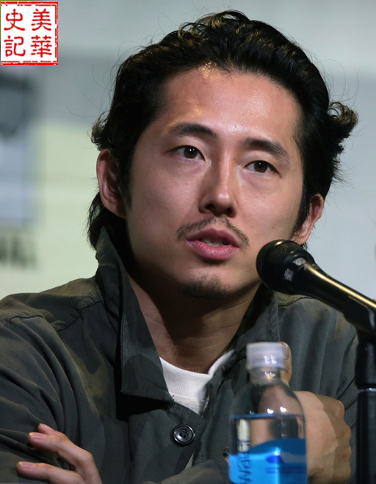

Steven Yeun (born Yeun Sang-yeop; December 21, 1983) is a first generation South Korean American who has starred in and served as an executive producer for Lee Isaac Chung‘s A24 immigrant drama Minari.

Haing Ngor (March 22, 1940 – February 25, 1996) was Cambodian American gynecologist, obstetrician, actor and author. He won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor For The Killing Fields (1984).

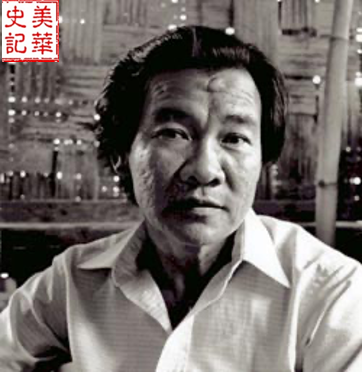

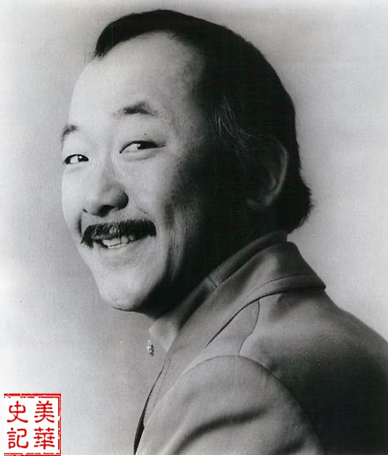

Pat Morita (June 28, 1932 – November 24, 2005)was a Japanese American actor and comedian. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for the film The Karate Kid (1984).

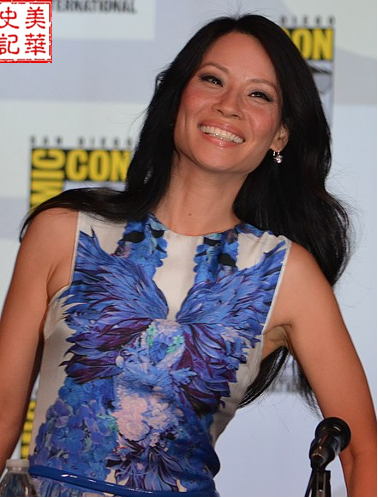

Lucy Alexis Liu (born Lucy Liu; December 2, 1968) is a Chinese American actress, producer and artist who has worked in both television and film. Liu’s parents originally came from Beijing and Shanghai and immigrated to Taiwan as adults before meeting in New York. She starred in “Charlie’s Angels”, Kill Bill: Volume 1, Lucky Number Slevin, and voices for all Kung Fu Panda movies.

M. Night Shyamalan is a first generation Indian American filmmaker and actor. His most well-received films include the supernatural thriller The Sixth Sense (1999), which got him nominated for Best Screenplay of 1999’s Golden Globe Awards and $650 million in ticket sales, the superhero thriller Unbreakable (2000), and the science fiction thriller Signs (2002).

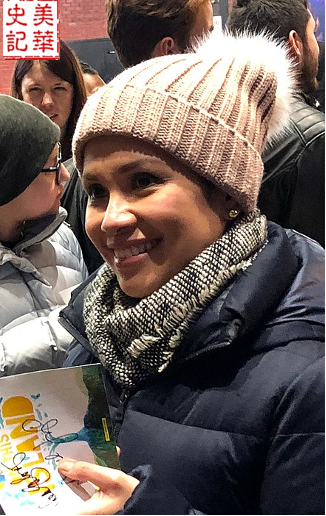

Sandra Oh was born in Nepean, Ontario, on July 20, 1971. She is the daughter of middle-class South Korean immigrants, Asian-Canadian-American, a television and film actor. She has been the face of Grey’s Anatomy and Killing Eve. On March 22, 2021, Oh gave a speech at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in response to the Atlanta spa shootings.

Singer and actress Lea Salonga (born February 22, 1971) is a Filipina singer and actress, who broke out in the lead role in the musical Miss Saigon, was also the first Asian to play the roles of Éponine and Fantine in the musical Les Misérables on Broadway, and is still active on Broadway

2.11 Musicians

Yo-Yo Ma (born October 7, 1955) is a Chinese American cellist. He graduated from the Juilliard School and Harvard University, and has performed as a soloist with orchestras around the world. He has recorded more than 90 albums and received 18 Grammy Awards. Ma was named Peace Ambassador by then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in January 2006.He is a founding member of the influential Chinese-American Committee of 100.In February 2011, President Obama presented him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Sarah Chang (born Young Joo Chang; born December 10, 1980) is a Korean American classical violinist. Chang has performed with all leading orchestras in the world including the New York Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony, the Boston Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Vienna Philharmonic.

Midori Gotō (born October 25, 1971) is a first generation Japanese American violinist. In addition to being named Artist of the Year by the Japanese government (1988) and the recipient of the 25th Suntory Music Award (1993), Midori has won the Avery Fisher Prize (2001), Musical America’s Instrumentalist of the Year award (2002), the Deutscher Schallplattenpreis (2002, 2003), the Kennedy Center Gold Medal in the Arts (2010), and the Mellon Mentoring Award (2012). In 2012, she received the prestigious Crystal Award by the World Economic Forum in Davos for “20-year devotion to community engagement work worldwide”. In May 2021 she was an honoree of the 43rd Kennedy Center Honors.

Tan Dun (born 18 August 1957) is a first generation Chinese American contemporary classical composer, pianist, and conductor for New York Philharmonic Orchestra, most widely known for his scores for the movies Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero, as well as composing music for the medal ceremonies at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

2.12 Writing

Iris Chang (March 28, 1968 – November 9, 2004) was a second-generation Chinese American author of historical books. She is best known for her best-selling 1997 account of the Nanking Massacre, The Rape of Nanking, and in 2003, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History.

Atul Gawande (born November 5, 1965) is a second-generation Indian American surgeon, writer, and public health policy researcher. He has written extensively on medicine and public health for The New Yorker and Slate, and is the author of the books Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science; Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance; The Checklist Manifesto; and Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End.

Khaled Hosseini (born 4 March 1965) is an Afghan American novelist and UNHCR goodwill ambassador.His novel The Kite Runner (2003) was a critical and commercial success.

Chang-rae Lee (born July 29, 1965) is a Korean American novelist and a professor of creative writing at Stanford University. Lee’s first novel, Native Speaker (1995), won numerous awards including the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. He was also a 2011 Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for The Surrendered.

Nilanjana Sudeshna “Jhumpa” Lahiri (born July 11, 1967) is an Indian American author. Her debut collection of short-stories Interpreter of Maladies (1999) won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the PEN/Hemingway Award, and her first novel, The Namesake (2003), was adapted into the popular film of the same name. In 2014, Lahiri was awarded the National Humanities Medal. She has been a professor of creative writing at Princeton University since 2015.

Anthony Veasna So (February 20, 1992 – December 8, 2020) was a Cambodian American writer known for short stories, which were described by The New York Times as “crackling, kinetic and darkly comedic” and often drew from his upbringing as a child of Cambodian immigrants. So died from a drug overdose in 2020, and his debut book, a short story collection entitled Afterparties, was published in August 2021.

Amy Ruth Tan (born February 19, 1952) is a Chinese American author known for the novel The Joy Luck Club, which was adapted into a film of the same name in 1993.

Tan has written several other novels, including The Hundred Secret Senses, The Bonesetter’s Daughter, and The Valley of Amazement. Tan’s latest book is a memoir entitled Where The Past Begins: A Writer’s Memoir(2017). In addition to these, Tan has written two children’s books: The Moon Lady (1992) and Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese Cat (1994), which was turned into an animated series that aired on PBS.

2.13 AAPI Outsized Impact on the U.S. Economy

Population

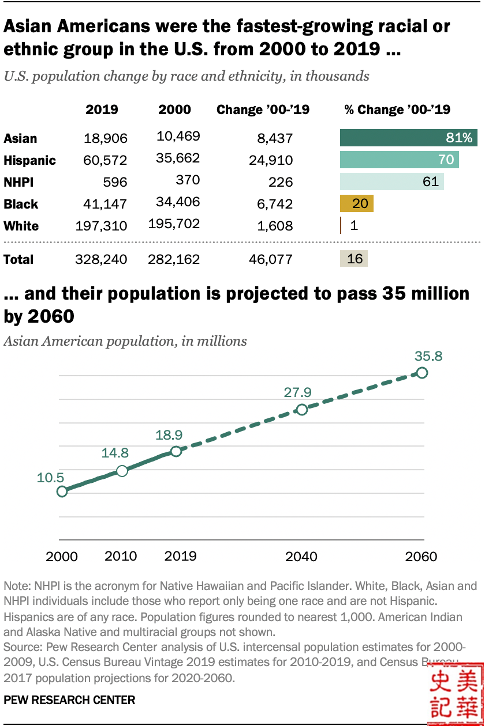

In the 21st century, people of South and East Asia have become one of the largest immigrant groups. Approximately 20 million AAPIs reside in the U.S. (Approximately 6% of the U.S. population according to the 2020 Census). By 2060, AAPIs would make up 9.7% of the total United States population — over 35 million people.

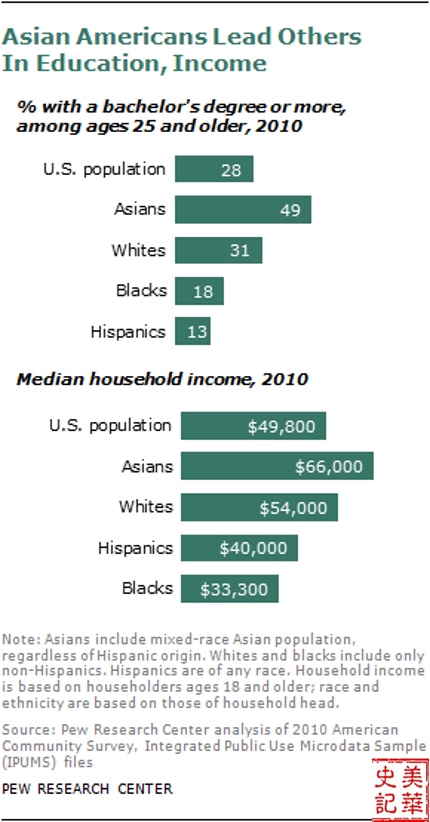

Education and Income

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders lead the nation in terms of average education and income.

Overall, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders continue to make outsized contributions to the U.S. economy. While Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders make up 5.8 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 7.0 percent of all household income earned and 6.8 percent of total spending power in the United States. This reflects the critical roles that they fill across the country as workers, consumers, and taxpayers.

3. Barriers and Discrimination

Showcasing AAPI history at the new AAPI Museum will help AAPIs learn about the hardships overcome by past generations, which gives them hope, pride, and an awareness that they have a generational mission to address.

3.1 Anti-AAPI Discrimination and Hate

From the historical gold rush to the modern COVID-19 pandemic, AAPI communities have long faced the critical issue of anti-AAPI hate and discrimination. There are widespread reports of Asian adults experiencing discrimination, regardless of their occupations.

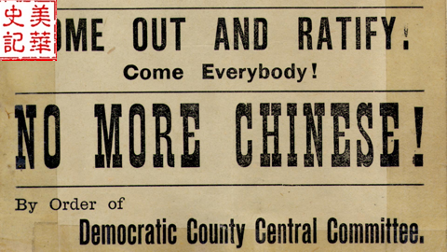

19th century media and politicians portrayed the Chinese as a threat to America and a “Yellow Peril”. They engaged in an extensive smear campaign to tarnish the reputations of the Chinese and stir up xenophobic sentiment and even allowed private civilians to attack and kill Chinese people.

The year 2021 marks the 150th anniversary of one of the largest mass lynchings in American history. The carnage erupted in Los Angeles on October 24, 1871, when a frenzied mob of 500 people stormed into the city’s Chinese quarter. Some victims were shot and stabbed; others were hanged from makeshift gallows. By the end of the night, 19 mangled bodies lay in the streets of Los Angeles. Ten percent of the Chinese population had been killed.

The Page Act, which was passed in 1875, masqueraded under the guise of maintaining morality and prohibited the immigration of Chinese women, making it nearly impossible for Chinese men in America to start families. By restricting the immigration of women, the federal government successfully limited the growth of the Chinese population (Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Chinese Woman in the 19th Century and the Page Act by Xin Su).

A few years later, “An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to the Chinese”, also called the Chinese Exclusion Act, was a discriminatory law signed in 1882 targeting Chinese Americans. In the beginning (from roughly 1882-1888), the law only intended to impose restrictions on Chinese immigrants. This would quickly change, as between 1885 and 1886 the United States experienced an explosion in violence against Chinese Americans. The change in public opinion was enough to steer the United States off the course of simply “controlling immigration” and down the path of complete exclusion (1888-1943; Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The First Decade of The Chinese Exclusion Act by Xin Su).

By 1892, measures such as the Geary Act required all Chinese residents in the United States to carry “certificates of residence” or “dog tags,” as the Chinese community tended to call them. Many Chinese immigrants began organizing to resist the enforcement of the law (Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The Second Decade of The Chinese Exclusion Act by Xin Su). The brave efforts of average Chinese Americans turned out to be one of the largest mass civil disobedience movements in U.S. history. With no allies anywhere, Chinese Americans were left with one choice: abide or else. In 1902, the complete exclusion of Chinese immigrants became a permanent law and the legal channel for Chinese immigrants would remain shut for another 40 years (Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The Third Decade of The Chinese Exclusion Act by Xin Su).

The Immigration Act of 1917 (Barred Zone Act) created a “barred zone” extending from the Middle East to Southeast Asia from which no persons were allowed to enter the United States and the Immigration Act of 1924 effectively banned all Asians coming to the U.S.

WWII closely linked China and the United States together in the international anti-fascist alliance, and many Chinese Americans actively participated in the anti-Japanese propaganda and war effort. Not only did they overcome the harsh domestic political environment of the exclusion period, their “popular” role in the war also won respect and sympathy.

With great love and deep sympathy for the Chinese people, Pearl Buck, alongside many other notable Americans, formed the “Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion”, whose political leverage was so influential that it successfully persuaded numerous organizations and members of the public to lobby Congress for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Finally, in 1943, Congress passed a new Immigration Act that ended the sixty-one-year old policy of Chinese exclusion.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/chinese-exclusion-act/ (PD)

February 2017 marked the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, a document that President Roosevelt signed in 1942, two months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The order resulted in the imprisonment of 75,000 Americans of Japanese descent and 45,000 Japanese nationals in prison camps across the country, with many being relocated far from home.

Among 60% of those interned, nearly 75,000 people in total, were American citizens. Many of the rest were long-time U.S. residents who had lived in this country for between 20 and 40 years. Many families had to sell their homes, their stores, their farms, and most of their assets immediately. Because of the mad rush to sell, properties and inventories were often sold at a fraction of their market value.

Japanese Americans were forced to relocate to ten concentration camps in remote areas of Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming. The living conditions of the camps were often poor, and the camps were fenced with barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers.

Despite being treated so unfairly, thousands of them joined the 442nd Infantry regiment in 1943, and fought bravely for their adopted country against Nazis. Some decorated soldiers later returned to visit their families in the camps, only to angrily find themselves being closely watched by armed soldiers who might have not fired a shot against their real enemy in the war.

Some 40 years later, the U.S. Congress finally formally recognized that the rights of the Japanese American community had been violated and President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided an apology and restitution to the living Japanese Americans who were

incarcerated during WWII.

AP Photo, AP Images Royalty Free

AP Photo, AP Images Royalty Free

On June 23, 1982, Vincent Chin was gruesomely murdered. His killers mistakenly believed he was Japanese (Chin was Chinese), who they blamed for a recent downturn in the American automobile industry. He was bludgeoned to death with a baseball bat. Despite their conviction and evidence, the killers never saw prison time and were only given light sentences.His killers, Ronald Ebens and his stepson Michael Nitz, were fined just $3,000 and given 3 years probation.

On March 16, 2021, we were all shocked to hear the news of the Atlanta spa shootings where six of the eight killed were Asian women – four Korean Americans, two Chinese Americans, and two Caucasians. This massacre is an example of a growing wave of violent anti-Asian sentiment in the US which has intensified in recent years, yet it was labeled as a result of the killer’s “sex addiction”. We can see from this that the reputation of Asian women remains tarnished by the discrimination of the past. Even in the 21st century, they are victims to the unfair stereotypes placed upon them.

In 2020, hate crimes overall increased last year by two percent, but hate crimes against AAPIs rose by 146 percent. Amid widespread reports of discrimination and violence against AAPIs during the pandemic, 32% of Asian adults say they have feared someone might threaten or physically attack them – a greater share than other racial or ethnic groups. The vast majority of AAPI adults (81%) also say violence against them is increasing, far surpassing the share of all U.S. adults (56%) who say the same, according to a new Pew Research Center survey (pewresearch.org, 21-Apr-2021).

The persistent and increasing Anti-AAPI hate crimes and incidents are tied to the fact that AAPI stories are missing from many U.S. classrooms. A National AAPI Museum can help address this significant lapse in our public education.

3.2 Mental Health Challenges

Recent data collected from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) found that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (2095 respondents) have a 17.30 percent overall lifetime rate of any psychiatric disorder and a 9.19 percent 12-month rate, yet AAPIs are three times less likely to seek mental health services than Caucasians.

According to the study there are three main causes for mental health issues among Asian American youth: parental pressure to succeed in academics, cultural stigma against discussing mental health issues which leads to tendencies to avoid approaching the subject or to neglect their symptoms, and discrimination/bullying due to racial or cultural background.

According to the study, many psychiatric disorders result from bullying in classrooms and the cyber world: over half of AAPI students who report being bullied say it occurs in the classroom, and 62 percent report being cyberbullied.

Among the types of bullying, more AAPI students (11 percent) reported being frequently targeted with race-related hate speech than was reported by Caucasian students (3 percent). Among AAPI students, immigrant and 2nd generation students were more likely to be victimized than 3rd or later generation students. Data on nearly 750 AAPI middle and high school students from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health suggest that 17 percent reported being violently victimized (e.g., had a gun/knife pulled on her/him, stabbed, cut or jumped) at least once in the past year (2019), according to American Psychological Association.

A nationwide AAPI museum would serve as an excellent platform to introduce different yet fascinating AAPI cultures to children of all backgrounds so that they can learn from each other and develop a more well-rounded understanding of other cultures. The museum would also provide them a powerful tool to prevent prejudice, discrimination and hate.

3.3 The Growing Income Inequality Within AAPIs

According to Pew Research Center, the median household income for AAPI households was $85,800 in 2019, slightly higher than the total U.S. median household income. Burmese Americans, however, bring in a household income of $44,400, about half of the median income for AAPIs.

This inequality is also related to the gaps in educational attainment within AAPI communities, as 2020 census data suggests that the amount of college education and income are positively correlated. AAPI communities should continue to advocate the idea that “it takes a village to raise a child” within communities to help our children do better in schools and prepare them to go into higher-earning occupations in society.

4. AAPIs Fought Back, and Everyone Benefited

Another crucial part of AAPI history is that AAPI’s fought back against unfairness, discrimination and overt violence; they have vindicated legal rights and remedies that have benefited everyone in the process. This notion of fighting back and winning is important because it shows AAPIs as actors in their own history, not defined solely as victims or people who were colonized, excluded or killed.

Immigration

After the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a group of Caucasian Americans in the Midwest launched a large-scale attack against the whole Chinese race. They were ruthless and unrelenting in their brutality, the details of which are included in our previous articles on the Chinese Exclusion Act. Some Chinese Americans quickly came to realize the value of fighting for their rights through litigation: it allowed for the atrocities committed to become recorded in the highest courts of law, and it also promoted lasting change. As a result, Chinese Americans began using the law as their weapon to fight the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act. In the first decade of the Chinese Exclusion Act alone, Chinese Americans fought more than 7,000 court cases, most of which they won. That is probably the single greatest contribution of the Chinese Americans: the power to expand upon and explore the possibilities of the law (refer to Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The Second Decade of The Chinese Exclusion Act by Xin Su).

Birthright Citizenship

The U.S. citizenship law is based on the two traditional principles of “jus soli” (born in American territory) and “jus sanguinis” (parental citizenship). Wong Kim Ark obtained his birthright citizenship by challenging the ruling of the U.S. law based on discrimination against Chinese (SeeHistorical Record of Chinese Americans | Wong Kim Ark And Citizenship: Right of the Soil and Right of the Blood by Fin Qi).

As a result of the new 14th Amendment, newly liberated slaves and all persons not subject to any foreign power were granted Birthright Citizenship as long as they were born in the United States. However, Birthright Citizenship did not apply to American Indians, since Indian tribes were considered to be outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. government (Note: Congress eventually granted full citizenship to American Indians via the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924). At that time, the proportion of the Chinese population was small and almost all of them were sojourners, so the Chinese were not under consideration for Birthright Citizenship.

Wong Kim Ark was not the first Chinese person to challenge how Birthright Citizenship was applied; a few others had acquired citizenship through legal actions, such as Look Tin Sing, a Chinese businessman who was barred from reentering the United States by immigration officers in 1884. Look’s case was heard in a federal circuit court in California by Judge Field. He won the case and was recognized as a U.S. citizen. But this case, like others pertaining to the question of Chinese citizenship, was not brought to the Supreme Court, resulting only in a low level of jurisdiction awareness about the situation.

Wong Kim Ark and his lawyers tried to link Chinese Birthright Citizenship to that of thousands of Caucasian immigrant children. On March 28, 1898, in a 6-2 decision, the majority concluded that “subject to the jurisdiction” meant all native-born children were citizens, excluding only those who were born to foreign rulers or diplomats, born on foreign public ships, or born to enemy forces engaged in hostile occupation of the country’s territory. Wong Kim Ark had finally acquired the citizenship that had long been denied to him.

Wong’s case set a precedent for the children of all immigrants and significantly affected the nation’s immigration history, redefining the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and “Birthright Citizenship”. Since then, everyone born in the United States, regardless of race, color, or parental status, is eligible to be a U.S. citizen.

Education

The California School Law promulgated in 1870 stipulated that only Caucasians qualified for public education, while African Americans and Indians could receive segregated education sponsored by the state. Unfortunately, the Chinese were the only ethnic group who were obligated to pay taxes, but had no right and no access to any education resources. During 1884-1885, a Chinese family, Joseph Tape and Mary Tape, hired a lawyer and sued the San Francisco Board of Education, California (Tape v. Hurley), starting the fight for equal rights in public education for Chinese Americans. Because of this lawsuit’s victory, the Chinese children obtained their right to receive public education in the United States (Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Seventy-year Struggle: Fighting Against School Segregation by Qian Huang).

Before 1950, many states in the United States practiced racial segregation in education: African Americans were not allowed to go to the same schools as Caucasians. In 1924, the Rosedale Consolidated School in Mississippi only accepted “Caucasian races” and did not accept Chinese children at all. A Chinese immigrant, Gong Lum, brought a lawsuit to the Supreme Court (Gong Lum, et al v. Rice et al, 275 US 78). Unfortunately, under the circumstances of that time, Lum lost the lawsuit and failed to change the situation of educational segregation. It was not until 1954 when the case of Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483, 1954) was won when the segregation situation finally started to change.

On May 17, 1954, the court ruled that segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This ruling also rejected the 1927 judgment in the case of Lum v. Rice based on the legal basis of segregation. From that time on, the descendants of Chinese immigrants in the southern United States finally saw the light of desegregation (refer toHistorical Record of Chinese Americans | Chinese American Figure: Katherine Lum And The Fight Against School Segregation In 1920s Mississippi by Zhida Song-James).

United Farm Workers

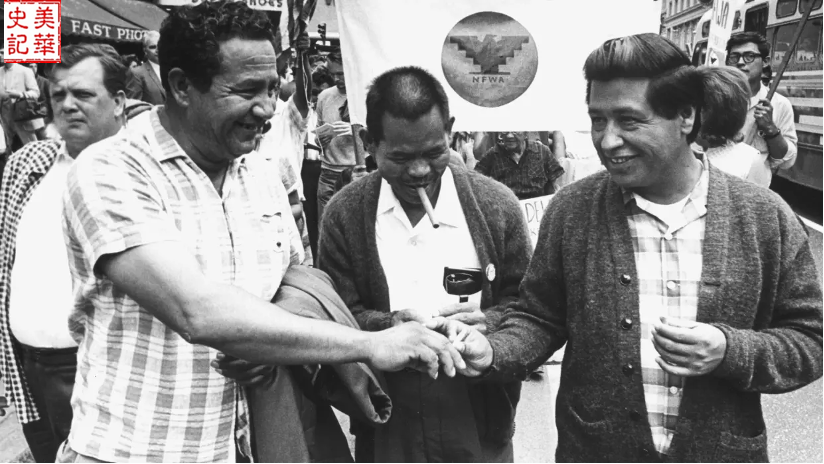

Photo by Gerald L French/Corbis via Getty Images, Getty Images Royalty Free)

On September 6, 1965, Filipino American grape workers organized a nonviolent strike (alongside Cesar Chavez and his Latino farmworkers union, the National Farm Workers Association) against table and wine grape growers in Delano, CA. It represented the first time a boycott was used in a major labor dispute. It also resulted in the merger of Cesar’s union and the Filipino workers’ Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, which together became known as the United Farm Workers. To date, the United Farm Workers has more than 10,000 members, making it the country’s largest farmworker union.

Senate Bill S. 2566 (114th): Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act

In 2013, Amanda Nguyen, the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, was raped while studying at Harvard University. At the time, Amanda still had to pay a significant amount of money every six months to make sure her rape kit wasn’t destroyed, even though rape kits in Massachusetts were supposed to be kept for 15 years, according to Money magazine. This challenge led Amanda to found Rise, a nonprofit organization that supports fellow sexual assault survivors, and to write the original draft of the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act. The bill, which was passed in 2016, gives survivors access to a forensic medical examination at no cost and allows them to preserve their rape kits without having to regularly request an extension. For her work, Amanda Nguyen was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.

This photo was taken of Amanda Nguyen in front of the Jefferson Memorial by Kate Warren.

American Citizens for Justice (ACJ)

Outraged by a judge’s lenient sentence on Vincent Chin’s killers, a group of Asian Pacific Americans formed the American Citizens for Justice on March 30, 1983, with the immediate goal of fighting for a retrial. Consisting of individuals of wide-ranging Asian descent including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino, this group represented for the first time, according to APA advocates and academics, that people who trace their ancestry to different countries in Asia and the Pacific Islands crossed ethnic and socioeconomic lines to fight as a united group of Asian Pacific Americans.

ACJ today works to combat xenophobia, hate in all its forms, and provides legal, social, and economic resources to victims of discrimination, and advocates for immigrants to gain full participation in the political process.

Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAJC)

Asian Americans Advancing Justice is a non-profit legal aid and civil rights organization dedicated to advocating for civil rights, providing legal services and education, and building coalitions on behalf of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (NHPI) communities.

AAJC has been working to increase the AAPI/NHPI community’s political power, and to promote equal protection by ensuring civil and human rights of all AAPI/HNPI are recognized and protected since 1983.

Appendices