Author:Xin Su

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

While the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 closed the legal door for immigration, many Chinese switched their tactics by entering the country illegally and they probably became US’ first illegal immigrants. Moreover, these illegal Chinese immigrants who had sneaked into the US through Canada, Mexico, or unguarded shores might have set a precedent for future unlawful immigrants. To prevent the breach of its border by illicit immigrants, the US government hence began to extend its border security to its neighbors such as border diplomacy in Canada and border policing near the border with Mexico. Despite the effective border security in both northern and southern sides, some Chinese managed to take advantage of legal loopholes to acquire admission to the country as legal immigrants or even citizens. In addition, during the third decade after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, many Chinese Americans had begun to embrace international politics. Led by the Protect the Emperor Society (Bao Huang Hui) and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (Zhong Hua Hui Guan), they called for and donated money to support the boycott of American goods across seas in 1905-06. They also contributed funds to the anti-Manchu revolution and some of them even returned to China to join the uprisings. In 1912, when the Chinese Exclusion Act entered its fourth decade, the last dynasty of the Qing Empire, which lasted thousands of years, finally came to an end.

~~~~~~

Anti-Chinese Immigration Walls Built on the North and South Borders

The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed by the US Congress in 1882, closed the door to legal immigration for the Chinese, but there was no wall behind the door [1]. The closed door did not prevent the Chinese from entering the US. They endured many hardships, hid in any possible means of transportation or cargo, bribed officials and intermediaries, risked their lives to break through barriers, and lived shameful lives because of their illegal identities, just to seek the American Dream.

This made the Chinese, a group of people from the prosperous but declining Qing Empire, the first and largest number of illegal immigrants in the US at the time [2].

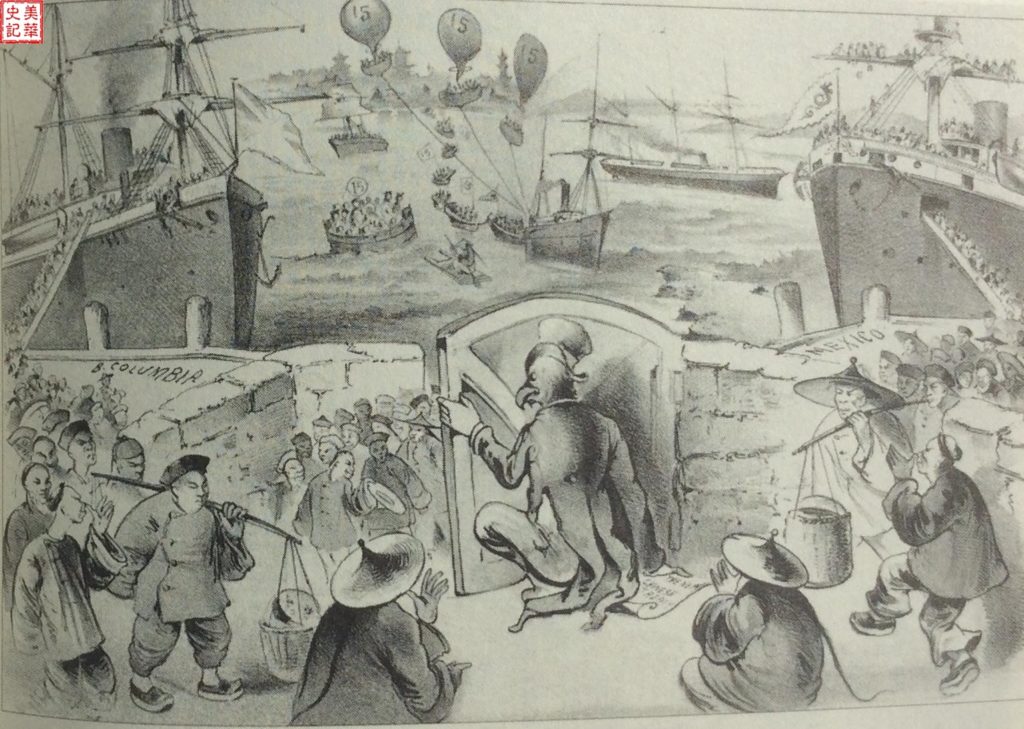

Picture 1, “And Still They Come!” This is the cartoon by The Wasp on December 4, 1880. The image depicts the irony that Americans were busy protecting the gates, while Chinese illegal immigrants still entered from Canada and Mexico. Picture courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, also Erika Lee, At America’s Gates. P167.

In fact, since the signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, illegal immigrants were no longer a myth: beginning from the Atlantic Gulf in the east, to the Pacific Port in the west, Canada in the north, and Mexico in the south, illegal Chinese immigrants flooded into the country. The huge profits made by officials who allowed illegal immigrants to enter caused immigration to be repeatedly banned from the Chinese [3].

For example, the immigrant Chen Ke did not bribe the translator when he entered customs in Boston, and the translator told the immigration officer that his document was forged. As a result, Chen Ke was sent home. In desperation, he paid $6,500 to get smuggled back in. He had borrowed the money, and it took 20 years of work to pay it off [4].

There were both European and Asian illegal immigrants, but Europeans were eagerly welcomed by the United States, whereas Asian immigrants were looked down upon, thus the Chinese had to smuggle themselves in [2].

The United States wanted to work with its neighbors in the north and south to deal with the illegal immigrants. However, the north and south borders operated differently. In the north, US efforts centered on border diplomacy based on a historically amicable diplomatic relationship and a shared antipathy for Chinese immigration. In contrast, US control over the southern border relies less upon cooperation with Mexico and more upon border policing, a system of surveillance, patrols, apprehension, and deportation [5,6].

There were two types of illegal immigrants from Canada. The first type was the Chinese who came to the US and had to cross the border to work in Canada. After the Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted, it would be difficult for them to return to the United States. The second type were those who went directly to Canada from China in order to reach the US. The border between the United States and Canada was wide and unattended to, so it was very easy for Chinese Canadians to cross the border to the United States [5]. An American journalist estimated that 99% of the Chinese arriving in Canada intended to “smuggle themselves over our border” [5].

Early on, Canada allowed Chinese people to pay head tax to enter. For example, in 1900, it cost each person 100 US dollars to enter, but in 1903, the fee grew to 500 US dollars per person. An Oregon magazine editor complained: “Canada gets the money, and we get the Chinamen.” It was true that Canada’s northern border had generated a steady stream of wealth. So at the beginning, the Canadian government was unwilling to actively cooperate [7,8].

Under constant pressure from the United States and the threat of closing the border, the United States and the Canadian Pacific Railway Transportation Company reached an agreement in 1903. All Chinese visitors must be checked to see if they meet the requirements for entering the United States. After the inspection, the qualified persons were sent to the designated U.S. border post for inspection. Those who passed the inspection would get a passport to enter the United States, and those who failed the inspection would return to Canada [8].

At the same time, the U.S. government realized that the acceptance of the Chinese from Canada would bring potential pressure for illegal immigration to the U.S. In 1908, the United States put further pressure on Canada, hoping for them to enact a Chinese Exclusion Act, similar to the one the US had in place. In 1912, Canada finally agreed to reject the Chinese who had been barred from entry by the United States. Under the dual pressure of the anti-Chinese sentiment by the US government and its private sector, Canada overhauled its Chinese immigration policies altogether to more closely mirror U.S. law. In 1923, Canada abolished the head-tax system and implemented the Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act [9].

Compared to Canada, the border situation in Mexico was very different. The boundary between the United States and Mexico was very vague, and it was difficult to tell if one was standing in Mexico or on the territory of the United States. Since the entry of a large number of Chinese promoted local economic development and provided products and services, Mexico’s President Diaz believed that if Chinese immigration were controlled like the United States, Mexico would lose a lot of valuable labor, so they were willing to accept Chinese labor. Mexican officials not only did not cooperate with the request of the United States, but also openly resisted it [10,11].

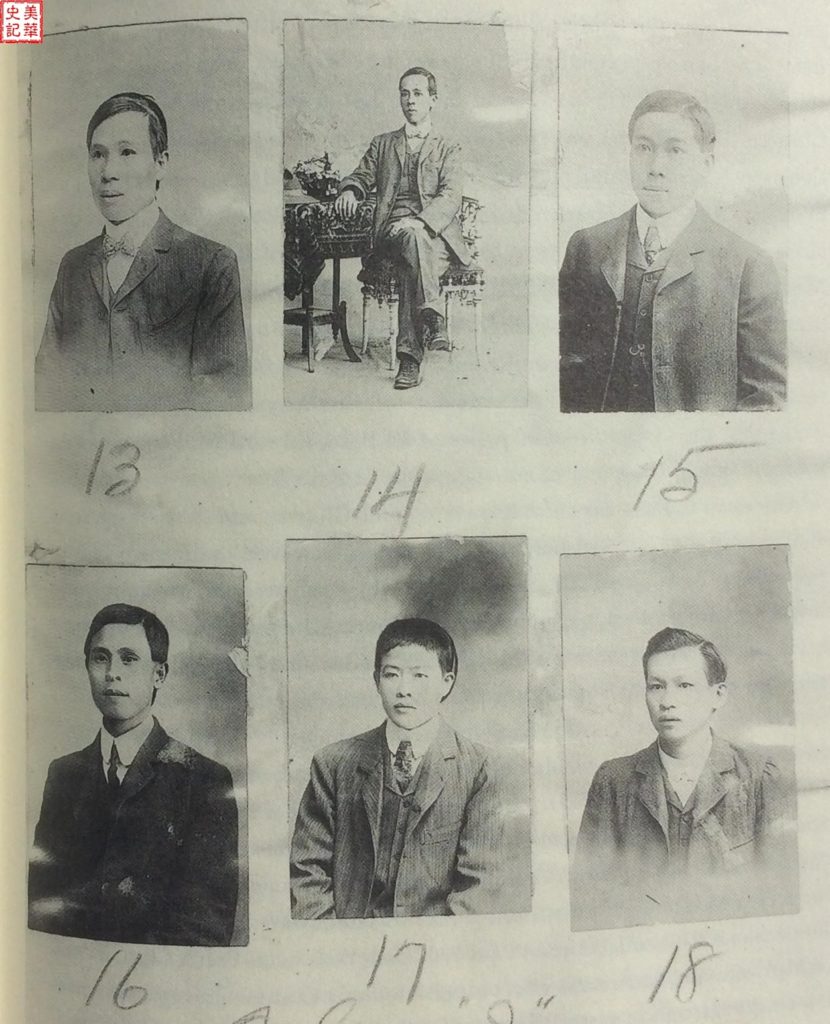

Picture 2,The Chinese used these photos to fraudulent Mexican citizenship papers as they smuggled across the southern border. Picture taken from Erika Lee, At America’s Gates. P163. National Archives, Washington, DC.

Some Mexican citizens and gangs helped the Chinese cross the border illegally and made a lot of money. One proudly said, “I have just brought seven yellow boys over and got $225 for that so you can see I am doing very well here.” [12] It is estimated that 80% of Chinese arriving Mexican seaports would eventually cross the border [12]. Some Chinese people disguised themselves as Indians or Mexicans and crossed the border [13].

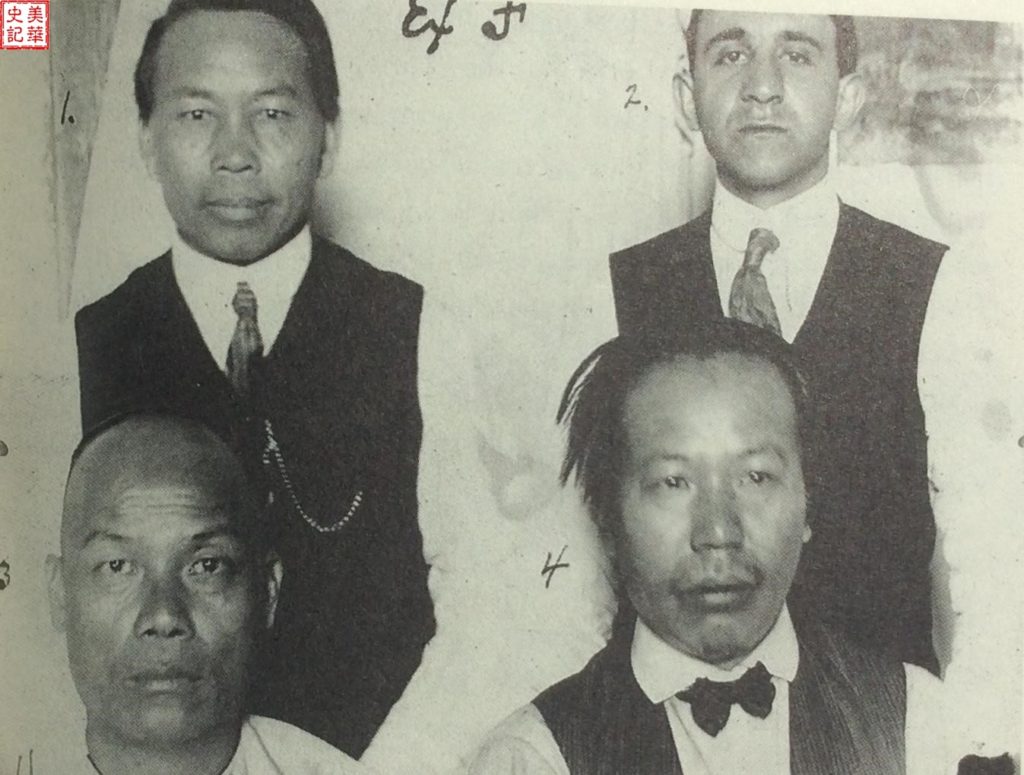

However, there were also Mexicans who helped the US Immigration Service catch smuggling. The US government offered rewards to those who provided intelligence on both sides of the US-Mexico border or helped catch illegal immigrants. These spies took photos of suspicious-looking immigrants and then sent them to boarder patrol. The clever spies were able to observe all sorts of suspicious people. Patrolling the border included all possible passages, pedestrian routes, car and train routes. In 1909, a comprehensive and systematic defense network was established. If the illegals were caught, they would face the fate of being brutally repatriated [14]. At the same time, anti-Chinese sentiment and anti-Chinese incidents began to grow in Mexico.

Figure 3, US immigration inspector Frank Stone posted a photo of himself and other “smugglers” who were caught in 1910. He went undercover in El Paso, Texas, to investigate Chinese “smuggling” activities. Picture taken from Erika Lee, At America’s Gates. P183. National Archives, Washington, D. C.

Immigration statistics showed that boarder surveillance, policing and deportation were very successful in preventing illegal immigrants from entering Mexico. The Chinese deported in 1898 accounted for 4% of those who entered Mexico, and in 1904 this percentage rose to 61%. In 1911, US border guard officials proudly declared that it was “no longer acting upon the defensive.” [15].

Border diplomacy with Canada and strengthened supervision of the US-Mexico border had been implemented, and the United States had effectively built a “wall” to prevent illegal immigration in both the north and south, which greatly reduced the problem of illegal immigration.

The gateway to legal immigration: Angel Immigration Island

Because the Immigration Bureau restricted the entry of Chinese labors, many Chinese people began to change strategies to enter the country as merchants or directly as citizens. Because children and grandchildren of citizens can stay, even someone who could have immigrated as a businessman was willing to fake and “become” an American citizen[16]. In this way, immigration became a mind game.

Chinese men who were already in the United States claimed that they were born in the United States and that their citizenship had not been registered yet [17]. Many Chinese claimed that the fire caused by the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 burned their birth certificates [18]. Chinese men who wished to enter the United States said they were the sons of their mothers who were pregnant and gave birth to their American fathers when they returned to China to visit relatives. In both cases, you can justifiably become a US citizen. After becoming a U.S. citizen, many people created more of these “paper sons” for their families or sold the slots to friends, neighbors, and strangers. [19] Some people often acted as middlemen in this scheme to make money. [20, 21]

Duncan E. McKinley, the Assistant U.S. Attorney, gave a speech at a Chinese exclusion conference in 1901, which reflected the problem of Chinese immigration fraud. He said, “Almost every morning there is a lawyer who claims that a Chinese man in his 20s was born in the United States. Witnesses who are also Chinese appear in court to testify, claiming that they had known the applicant twenty or twenty-five years ago. And that he was born in room 13 on the third floor of 710 Dupont Street. And that when the boy was 2 years old, he was taken by his mother to China for education. Now both parents are dead and relatives in the United States need him to take care of the business. And the uncle or cousin will also be there to swear to prove the truth of the matter. This story is too common, the evidence is solid, and the plan is well planned.” In 1901, a federal judge noted, “If all the stories told in the court were true, every Chinese woman who was in the United States 25 years ago must have had at least 500 children.” [22]

This kind of Chinese “cunning” bewildered immigration officials. For the Chinese, building relationships was more important than the law. According to the Chinese way of thinking, there was nothing immoral about wanting rights to live in a country. These human rights were innate. Since God did not say that the Chinese should not come to the United States, helping innocent Chinese gain entry should also be regarded as a good act. The moral bottom line is that the kin should support and aid one another. In this way, loopholes in the law have allowed populations of ethnic groups to grow [23].

The fire after the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 destroyed all public birth certificates. If there was no document, then the proof of citizenship could only be based on words. In the following years, a large number of “paper sons” appeared in San Francisco. The issue of “paper sons” greatly troubled the Immigration Bureau.

In order to identify the authenticity of these claims and truly implement the Chinese Exclusion Act, local governments in the United States believe it necessary to establish an interrogation process to ensure the truth of these oral claims. Most European immigrants entered the country from the East Bank, while the Chinese mostly entered the country from the West Bank. At first, the newly arrived Chinese in San Francisco were confined in a windowless two-story building on the side of the Pacific Cruise Line’s dock, which was very dirty and full of the smell of sewage [24]. The government wanted to establish immigration station that could prevent escape and that was isolated to the outside world, so Angel Island was an ideal location.

The island had a beautiful name, because in 1775, a Spanish warship entered the San Francisco Bay for the first time under the command of officer Juan de Ayala. Ayala’s warship docked on the island and gave it a more modern name (Ángeles) [25]. Angel Island used to be a military fortress, a public health service quarantine station, and an immigration office. The immigration station in the northeast corner detained and inspected immigrants from 84 different countries, about 175,000 of which were from China [26]. In 1940, a fire destroyed the island’s administrative building, and the immigration process was moved to San Francisco.

The United States Congress approved the construction of an immigration station on Angel Island in 1905. The immigration station was completed in 1908 and officially opened in 1910. [27] The bay where the island is located is commonly known as China Cove, because it was mainly used to control the entry of the Chinese into the United States. [28] One of the immigration inspections conducted by the Angel Island customs was routine sanitation and health inspections. Very few Europeans and American citizens were required to be checked and when they were, the doctors fairly abided by the hygiene regulations. [29] However, with the inspection of Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian immigrants, they were harsh and brutal in their inspection. In addition to standard inspections, Chinese immigrants also needed to take stool samples for intestinal parasite testing [29]. The Chinese who were diagnosed with the disease would be sent to the hospital on the island until they could pass the medical examination and immigration hearing. [30] The length of Chinese immigrants’ detention at the Island varied from two weeks to two years.

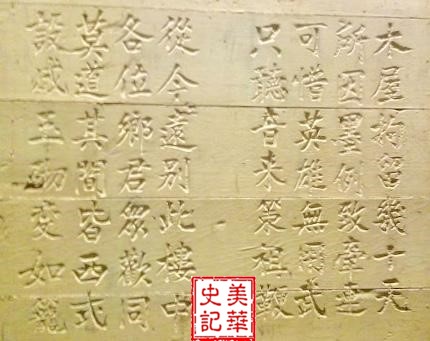

The interrogation process took an average of 2-3 weeks, but the review of certain immigrants could take up to several months. Each immigrant was interrogated individually by two immigration inspectors and a translator. The immigration officer asked hundreds of questions, including the details of the immigrant’s family and village and the specific circumstances of his or her ancestors, such as “Which direction does the door of your house face?” and “How old is your grandmother?” Their witnesses and other family members living in the United States would be asked the same questions for verification. Any deviation from the testimony would lead to prolonged questioning, and when customs officials suspected anything wrong, the applicant faced the risk of deportation. How did the Chinese overcome this obstacle? They prepared and memorized these details months in advance to make sure every word was perfect.

Picture 4, A note hidden in the peanut skin, which records the “correct answers” to the questions by the immigration officer. Picture taken from Erika Lee, At America’s Gates.P214. National Archives, Washington, D. C.

Picture 5, A note hidden in a banana peel, which records the “correct answers” to the questions by the immigration officer. Picture taken from Erika Lee, At America’s Gates.P215. National Archives, Washington, D. C.

The detention center on Angel Island was like a prison. The door of the barracks was locked all day long, the windows and the walls outside the courtyard were covered with barbed wire, and guards with loaded guns stood guard. Detainees had only a limited number of hours a day to breathe fresh air in the yard. As soon as the detention center was built, the detainees began to carve poems on the walls of the barracks to express their emotions. Three months later, the director of the Island claimed the poems to be graffiti, so he covered it with paint, but the poems were engraved once more. Some of the verses are as follows:

Picture 6, “Trapped in the wooden house for many days, because of regulations. If only heroes could realize their power, but they only have music to stay alive.” The next poem painted on the walls of the Angel Island immigration detention center. The photo is from Angel Island Immigration Station.

“When I came to America, I was arrested in a wooden building and turned into a prisoner. Americans do not approve of us and turn us back. Upon hearing this news, I am worried about how to return home. China is weak and the Chinese are not allowed here.”

“Trapped in the wooden house, worried and depressed. I wonder how my hometown is. My family wants to know how I am, but who will tell them if I am safe?”

These slightly clumsy, unrhythmic poems have eroded over time, but have not disappeared, expressing the infinite sadness, uncertainty, confusion and indignation of the detainees. These poems were published by well-known Chinese historians Him Mark Lai, Judy Yung, and Genny Lim in 1980. They were compiled, collated, and translated into a Chinese-English Collection of Poems [31] .

“My father came to the United States in 1921 and was detained on Angel Island for two months,” Professor Yang Yuefang said in an interview. “But then he never mentioned this experience to me, mostly because he was a ‘paper son,’ and that memory was not pleasant to him.”[32]

“If you suddenly find out that your last name is fake, how would you feel?” This is what happened to many Chinese-American families who came to the United States before World War II. Though Chinese workers entered the country legally, and tens of thousands of illegal Chinese forged documents to enter the United States. Today, the descendants of “paper son” are uncovering the truth, restoring the truth of their predecessors and allowing future generations to live without this shame.

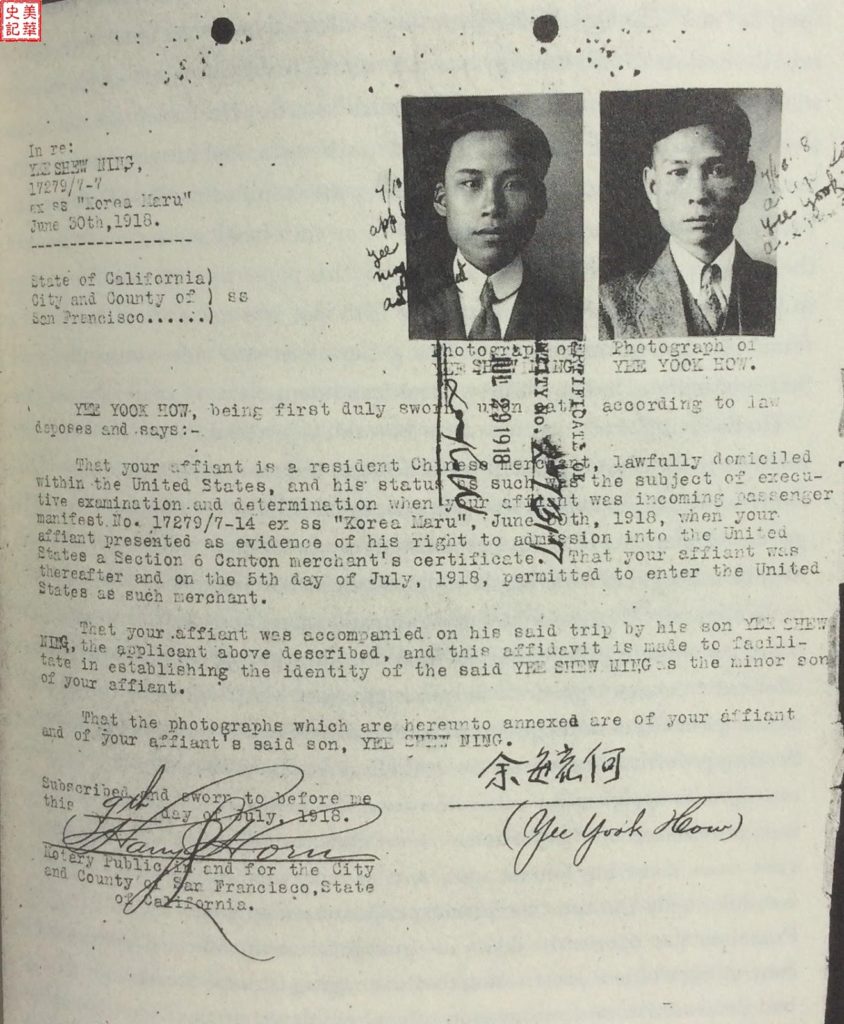

Picture 7, The documents purchased by the laborer Lee Chi Yet (paper name: Yee Shew Ning) to prove that he was the son of a businessman Yee Hook Haw. Picture taken from Erika Lee, At America’s Gates.P205. National Archives, Pacific Region, San Bruno, California.

Steve Kwok (Guo) was a descendant of ordinary immigrants. He once wrote an article called “My Dad is a Paper Son.” His father, like thousands of others, bought a paper identity. After careful inspection and review by the immigration officer, as well as a comparison of his appearance with his paper father and paper brothers, the officials believed they looked similar. Judging by the evidence provided, his claim seemed true, so his immigration application was approved. “Our family also thinks that Dad looks more like his paper brother than his real brother,” Steve added. When his father set foot in San Francisco, he had nobody to count on. He worked hard as a fruit picker, restaurant dishwasher, assistant chef, cashier, and restaurant manager. Many years later, when he repaid the cost of his paper identity and ferry tickets, he helped his real brother immigrate to the United States through the “paper son” method. It was not until the 1960s when the Chinese were granted immigration amnesty that they did not have to hide behind these fake identities. The family finally changed the “paper surname” back to the family surname. Later, Steve visited his hometown in Guangdong Province, China, and truly understood why a “paper son” had such courage and tenacity to immigrate to the United States to pursue a happy life. He said, “When we saw the primitive living conditions, we were both grateful that our Dad, a “Paper Son”, had the courage, fortitude and endurance to seek a better life in America. ” [33]

The Chinese Exclusion Act was accompanied by corresponding countermeasures and even crimes that occurred among the Chinese, causing generations of Chinese immigrants to live in fear, self-pity, shame, and anxiety.

The Chinese boycott of American goods to oppose the Chinese Exclusion Act

In the two decades since the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed, many Chinese immigrants in the United States had been subjected to endless killing, robbery, deportation, and discrimination. Around 1890, there was a plague epidemic in parts of the world, including Hong Kong, and the Chinese could not migrate to the American mainland via Honolulu. During this time, San Francisco closed Chinese companies and ordered all migrating Chinese to be vaccinated. [34] A group of medical experts pointed out that the advanced civilization of the United States would do everything to prevent being contaminated by foreign diseases. The plague was an “Oriental disease” and was produced by contaminated Asian soil [35]. On October 11, 1903, the immigration officials raided Boston’s Chinatown and arrested 234 Chinese because they were unable to produce their documents in time. In fact, only 45 people were illegal immigrants, and the rest were caught by mistake. [36] In May 1905, Ju Toy, a Chinese person born in the United States, was denied landing (Ju Toy v. United States) after visiting China and was deported by immigration officials [37].

In response to all kinds of discrimination, the Chinese turned to their home country for help. The Protect the Emperor Society established by Kang Youwei, who was in exile after the failure of the Hundred Days’ Reform (or Wuxu Reform), and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association called on the Chinese people overseas to boycott American products to pressure the United States, demanding that the United States treat Chinese immigrants better [38, 39].

The Protect the Emperor Society was the initiator of the boycott of American goods. The Protect the Emperor Society widely promoted the concept of boycotting as early as 1903. They mobilized Shanghai businessmen to put pressure on Qing government officials to support the boycott, and to spread the boycott through newspapers. At the end of April and early May, Kang Youwei sent a telegram from Los Angeles to the leaders of the Protect the Emperor Society in various places, asking everyone to put pressure on the government. Kang Youwei said that it was a question of life or death [38, 39].

Picture 8, Kang Youwei, president of the Protect the Emperor Society. The Protect the Emperor Society was a political group founded by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao in the late Qing Dynasty in China, with the main purpose of advocating a constitutional monarchy. In 1906, the Qing government adopted the policy of establishing a constitutional monarchy by 1911, and Kang Youwei declared that the mission of the Protect the Emperor Society was complete. In 1907, the Protect the Emperor Society was reorganized into the Empire Constitutionalist Association. It included 70,000 members from several countries. It is said that one-third of Chinese Americans were members of the Protect the Emperor Society and paid dues. Photo taken

Liang Qichao, a disciple of Kang Youwei and vice president of the Protect the Emperor Society, also advocated boycotting American products that were a part of the private corporations. He believed that if citizens oppose the government, the government may be too weak to succeed. Indeed, although the Qing court opposed the US’s immigration policy to China, the government was too weak to compete with the US government.

Picture 9, Liang Qichao, vice president of the Protect the Emperor Society. Picture taken

If the large-scale resistance of 110,000 Chinese in the United States rejecting to carry a resident permit in 1892 enabled the Chinese Americans to achieve unprecedented unity (http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/GA-EKEe8l4HCgf7DabhMew), then the 1905 boycott of American goods once again witnessed the unrivaled determination of Chinese people around the world to collectively resist discrimination. Businessmen, laborers, journalists, Christians, and all Chinese immigrants across the United States put aside their differences and united for a common goal of defending their rights.

The Chinese Americans indirectly participate in the domestic boycott of American goods through generous donations. The funds donated by the Chinese were sent to Shanghai, Guangdong, Hong Kong and other places through various channels. The Chinese vividly described to the Manchu and Qing people the adverse effects and harm caused by the Chinese Exclusion Act to the Chinese in the United States. Some Chinese Americans even returned to mainland China to share their experiences in the United States. The people of the Qing Dynasty were angry at the abuse their compatriots suffered in the United States, and were ready to take action to support the immigrants [40, 41].

In May 1905, when the U.S. plenipotentiary William W. Rockhill arrived in Beijing to negotiate a Sino-U.S. treaty, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and the U.S. Protect the Emperor Society sent telegrams to various departments of the Chinese government urging them not to sign anything that could restrict Chinese immigration.

On May 10, the board of directors of the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce agreed to respond to the call and boycott American products. Subsequently, the leader of the Chamber of Commerce Zeng Shaoqing sent a telegram requesting the business associations of 21 cities across the country to jointly take action. This call received a positive and enthusiastic response, and anti-American sentiment boiled across the country.

Immediately afterwards, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce proposed to the United States a condition in regards to the reassessment of its immigration policy towards China within a two-month period. If this requirement was not met, the United States would face large-scale economic resistance.

On July 16, 1905, four days before the deadline, a Chinese named Feng Xiawei committed suicide in front of the US Consulate in Shanghai. He was mistakenly arrested and deported by Boston immigration officials. The little-known man used his death to protest the unfair treatment he suffered in the United States. He became a hero overnight. This incident led to a large-scale boycott of American products that began on July 20. [38]

This was a nationwide peaceful boycott. Held in most Chinese cities including Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, Sichuan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Jilin, Zhejiang, Shanxi, Shandong and Hebei, involving all sorts of people–businesspeople, scholars, students, laborers, women, and children from all walks of life. Merchants stopped ordering or selling American products, such as cotton textiles, oil, matches, cigarettes, flour, and other daily-use items like soap, candles, cosmetics, hardware, and stationery. U.S. ships were not allowed to unload at the docks, and newspapers refused to publish advertisements for U.S. goods. Students and artists created artwork or literary works to describe the suffering of Chinese in the United States to oppose the Chinese Exclusion Act. [40, 41]

The boycott not only existed within China, but also extended to Chinese groups in other countries and regions such as the Philippines, Singapore, Japan, and Hawaii. Between July and September 1905, China’s boycott movement reached its climax. The United States lost about 30-40 million dollars. [41, 42, 43, 44]

The US government had to intervene and put pressure on the Qing government. The attitude of the Qing government changed from sympathy to suspicion and even to hostility. Because such resistance could quickly turn into an anti-government movement. At the beginning of the movement, public opinion pointed out that the Qing government was weak and could not protect its overseas people. After the peak of the boycott, businessmen, especially those who had business dealings with the United States, gradually faded out of the boycott movement. Boycotting U.S. goods was detrimental to the economic interests of Chinese businessmen. [38, 42]

At that time, the U.S. policy toward China was open to trade and closed to immigration. This was very contradictory, as China noted. Open trade had great economic benefits for China. This is when China lost control of the situation. The Qing government could only hope to satisfy these greedy economic benefits. [38, 42]

The Qing government did not mind the fate of Chinese Americans in the United States.

The vigorous boycott movement ended hastily at the end of 1905 and early 1906. Although this anti-American boycott did not shake the Chinese Exclusion Act, US Secretary of Commerce Metcalf and President Roosevelt recognized the US’s discrimination of the Chinese. President Roosevelt issued a presidential decree, ordering the Immigration Bureau to stop injustice against Chinese, and emphasized that the Chinese Exclusion Act was only for labor and should not be expanded to other domains [41, 45,46].

The anti-American economic boycott of 1905-1906 had quite an impact:

- For Chinese Americans, it prevented some people from attacking the Chinese in Chinatown. [47] Also, it reversed some discriminatory practices against Chinese. For example, the method of judging criminals based on physical conditions (Bertillon) was no longer weaponized against the Chinese [45,46].

- For the Protect the Emperor Society, this movement demonstrated the potential of Chinese citizens to participate in the cause of nationalism. It also tested the action of the Protect the Emperor Society and the influence of their newspapers.

- In mainland China, this kind of rebellious spirit inspired Chinese officials, literati and local businessmen. It marked the beginning of popular politics and modern nationalism in China.

- This movement was indeed an act of solidarity between Chinese across the border. When the Qing government was weak at that time, overseas activists tried to help and guide democracy and politics in the home country.

The Unprecedented Anti-Imperial Campaign of Chinese Americans

The year before the “Chinese Exclusion Act” entered its third decade, on September 9, 1901, the Qing government signed the Xin Chou Treaty again after a series of rather humiliating treaties. The once prosperous Qing empire had three hundred years worth of history, and it was just as unpopular as the rule of other dynasties and empires. The anti-Qing flames sparked from its citizens and spread to the overseas Chinese.

In 1903, 37-year-old revolutionary Sun Yat-sen traveled to Europe and the United States to preach revolution, and arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii on October 5. Although Sun Yat-sen was an offender of the imperial court, Honolulu and the Qing court had no diplomatic relations, so Sun Yat-sen had no security issues. However, at that time, most of the Chinese immigrants in the US supported the Protect the Emperor Society, so Sun Yat-sen experienced some difficulties [48].

The early Chinese immigrants had a system of clans or patriarchs. You could join a clan group or gang in exchange for protection. This was an extremely important concept throughout the history of the immigrant Chinese.

Hongmen was an anti-Qing gang organization. Hongmen was introduced to San Francisco as Zhi Gong Tong, which was later renamed Jinshan Zhi Gong Tong. A hundred years ago, seven out of the ten Chinese communities in the major cities of North and South America were Hongmen members. Hongmen members included people from all walks of life. The membership was first introduced by its old members, approved by the higher-ups, and then it was open for recruits [49].

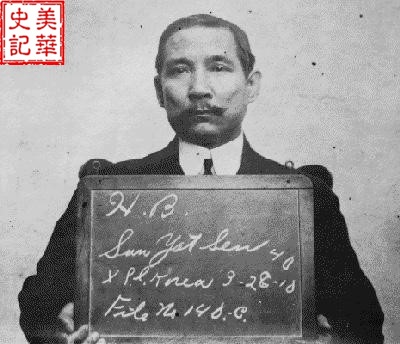

The leader of the Zhi Gong Tong, Huang Sande, and Sun Yat-sen’s brother Sun Mei were friends. In 1903, Huang Sande went to Honolulu to meet with Sun Yat-sen (to be verified for recruitment), and he revised his book to all the brothers in the Honolulu Guoan Guild Hall. The following year, on March 31, 1904, Sun Yat-sen was funded by the Guoan Guild Hall and took the Koryo ship to San Francisco [48,49]. Sun Yat-sen took the trip to the American continent for the purpose of propagating the revolution and soliciting donations.

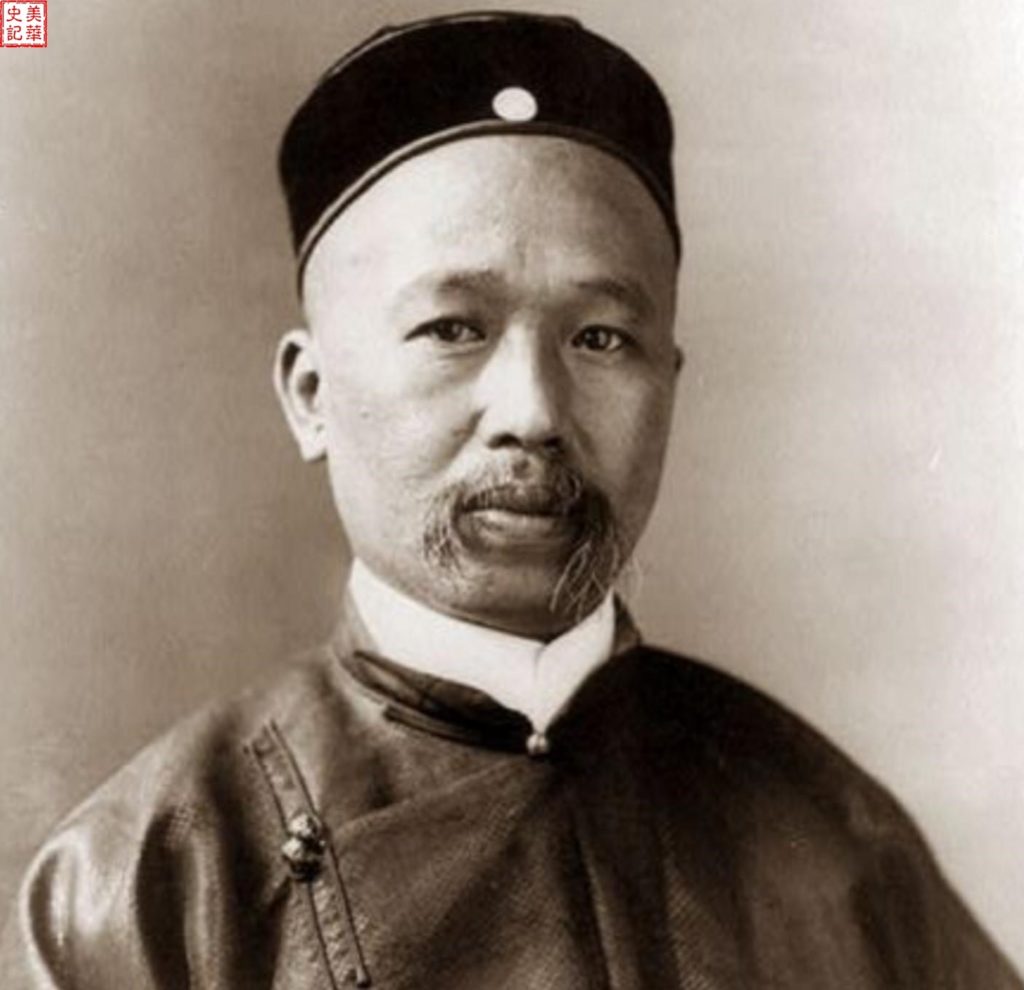

Picture 10, Sun Yat-sen was arrested when he entered the United States in 1904. It is said that Sun Yat-sen used the U.S. passport obtained by his “paper son” when he entered the country. People from the Protect the Emperor Society reported that there was a problem with his passport [50, 51]. Huang Sande spent $500 to bail him out of jail, and then spent $5,000 to ask a lawyer to bring him out of danger [52]. Picture taken

The Hongmen Zhi Gong Tang combined the revolution’s idea with Hongmen’s “anti-Qing and restoration of Han,” and called on overseas Chinese living in foreign countries to donate money to support the revolution. Overseas Chinese themselves also lived in the lower classes of American society with limited income, so their donations only amounted to a few cents each. However, these meager donations raised huge sums for the military. By the widespread fundraising, it is clear to tell that the cause had many donors [49].

The leaders of the league and the branch associates were the “rulers”–they exercised power in the name of the gang, and everyone had to obey. Knowing this, it’s easy to understand the politics and history of gangs as well as their appeal. It was Huang Sande, the leader of Hongmen Zhi Gong Tang, who supported the revolution and set off this campaign to raise funds. In 1904, he traveled to more than 30 cities to raise funds, which lasted half a year.

Picture 11, Huang Sande, a native of Dongtou Village, Jitan Township, Sijiu Town, Taishan County, Guangdong Province, was born in a poor peasant family in 1863. He had only three years of private school education. In 1878, Huang Sande was 15 years old. He borrowed money from relatives to go abroad to explore the “Golden Mountain” (San Francisco). He worked as a miner, a laundry worker, and also trained in martial arts. In December 1883, Huang Sande joined Hongmen. In 1897, at the age of 34, he was elected as the leader of the Hongmen Zhi Gong Tang and the premier of the Zhi Gong Tang. He was deemed the “Hongmen Gangster.” On October 14, 1946, Huang Sande passed away in Los Angeles. Ten thousand people attended his funeral [52, 53]. Picture taken

Situ Meitang was an overseas Chinese leader of Anliang Tang under the jurisdiction of Hongmen Zhi Gong Tang in the United States, and the prime minister of Zhi Gong Tang in Boston. When Huang Sande wanted to raise money in 1904, he introduced him to Sun Yat-sen. Since then, Situ Meitang also become one of the leaders of the overseas Chinese who faithfully followed Sun Yat-sen. He organized many events to support domestic revolutionary activities in terms of human and financial resources. That year, Huang Sande was 41 years old, Sun Yat-sen was 38 years old, and Situ Meitang was 36 years old.

Picture 12, Situ Meitang, from Kaiping, Guangdong. Because of childhood poverty, he boarded a ship sailing to the other side of the ocean in March 1882 to seek prosperity in the New World of America. At the age of 17, he joined the Hongmen Zhi Tong Tang. Situ Meitang died in Beijing in 1955. Picture is taken

In order to support Sun Yat-sen’s revolution in the Americas, Huang Sande reorganized the Datong Daily, the official newspaper of the Zhi Gong Tang, and revised the articles of the association. The boundary between Zhi Gong Tang and Protect the Emperor Society had been clearly drawn [49].

After the great debate on the basic issues of the democratic revolution from 1906 to 1907, the overseas Chinese began to support the revolutionary party. The big debate was between the revolutionary “Min Bao” headed by Sun Yat-sen against the “Xin Min Cong Bao” of the constitutional reformists led by Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao. [54]

In 1907, Huang Sande raised more than 7,000 US dollars for the Nanguan Uprising led by Sun Yat-sen. In December of the same year, Huang Sande took the advice from the Hongmen and sold or mortgaged the branch buildings in Vancouver, Victoria, and Toronto, raising huge sums of hundreds of thousands of dollars to fund Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary activities. [53]

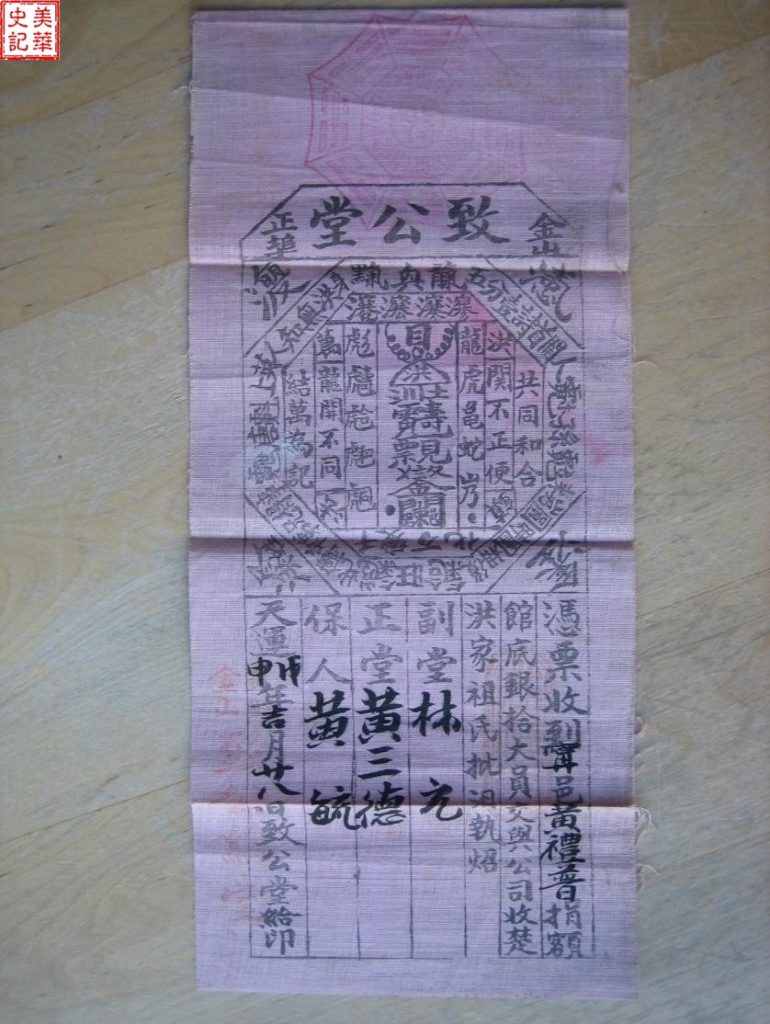

Picture 13, Huang Sande issued the Hongmen receipt for the newcomer Huang Lipu that received the “Top Ten Bankers” (“To Gongtang Jinshan Zhengbu”). The central part was a pattern composed of the Hongmen logo and the Hongmen secret language. The date was February 29, 1908 (the 28th day of auspicious month in the Wushen Year of Tianyun). The membership fee for newcomers was two yuan, and the amount of this vote was eight yuan more than the stipulation, which was an extra part of the charity donation. Picture taken

On March 29, 1911, Huang Sande went to Chicago to talk with Sun Yat-sen. During the conversation, Huang Xing, a revolutionary, called to inform them of the failure of the Guangzhou Uprising. In order to rescue the comrades who fled to Hong Kong, they needed 100,000 Hong Kong dollor. Huang Sande immediately returned to San Francisco and held a meeting with the leaders of the Zhi Gong Tang to raise sufficient funds [49].

Picture 14, Sun Yat-sen and the members of Zhi Gong Tang. Picture taken

In order to aid the revolution and provide timely financial assistance, in the summer of 1911, the Hongmen Finance Bureau was formally established and elected Zhu Sanjin as the chairman, Luo Yi as the vice chairman, and Huang Renxian, Guan Jiqing, and Liu Juke as the Chinese secretaries, and Tang Qiongchang and Huang Boyao as the English secretaries. Li Gongxia was the treasurer, and Huang Sande was the chief supervisor. The Hongmen Finance Bureau called on the overseas Chinese to actively donate funds and pledge donations from branches across the Americas. [55]

Even after Sun Yat-sen led many failed rebellions, Chinese Americans continued to donate and support him under the leadership of Hongmen Zhi Gong Tang. In addition to providing funds to support revolutionary activities, some people also returned to their hometowns to establish revolutionary organizations to contribute to the October Wuchang Uprising.

Huang Sande was a strong supporter of Sun Yat-sen. According to Huang Sande, after the Revolution of 1911, he “planned for several days and sent dozens of telegrams a day in the name of courts in various towns and various Chinese groups to support Sun Yat-sen as president. The cost of telegrams exceeded 1,000 dollars.” [53] On January 1, 1912 (November 13, Xinhai Year), the Nanjing Provisional Government was established, and Sun Yat-sen served as the Provisional President. At 10 pm, the inauguration ceremony of the Provisional President of the Republic of China was held at the Presidential Palace in Nanjing.

Figure 15, Donations by the Finance Bureau in the Americas [55]

After the compromise between Beiyang commander Yuan Shikai and the Southern Revolutionary Army, the last emperor Puyi was forced to issue an abdication edict on February 12, 1912 (fourth year of Xuantong). The Qing Dynasty, which had ruled China for 268 years, came to an end. Since then, the Chinese nation entered a deep and fierce war of warlords.

~~~~~~

The relationship between overseas Chinese and their home country have changed along the course of history. Initially, in the Qing government’s eyes, emigrating overseas was a violation of laws and ethics. At that time, the Qing court believed that humble merchants and laborers were not worthy of the protection of the Qing empire. The massacres of Chinese in foreign countries received no aid from China, as they did not establish any relationship with their home country’s government. This indifferent government attitude caused tens of thousands of overseas workers to be humiliated and hurt to varying degrees on the land of other countries. [56]

However, in the 1870s, when the Qing government encountered economic difficulties, some officials realized that they could raise donations from overseas Chinese to help the country. At this time, the Qing government began to pay attention to overseas Chinese. However, at the peak of the anti-China movement in the United States, the Qing government was in a dilemma of internal and external troubles and had no time to protect itself. China’s national power was too weak, and the United States could completely ignore any official Chinese protests[56]; not only that, in 1892, the protest of Chinese Americans wearing “dog tags” and the failure of China’s boycott of American goods in 1905 proved that the Qing government was sacrificing the interests of overseas Chinese in exchange for the home country’s temporary economic benefits.

The history of the third decade of the Chinese Exclusion Act demonstrated how overseas Chinese survived tenaciously in the harsh political environment of hate and discrimination. When the home country needed it, they still made every effort to support.

Reference:

1. Erika Lee, “At America’s gates : Chinese immigration during the exclusion era, 1882-1943”. (University of North Carolina Press, 2007): P173

2. Lee, 2007: P169-172

3.Lee, 2007: P148

4.Iris Chang, “The Chinese in America: A Narrative History” (Penguin, 2003): P156.

5.Lee, 2007: P152-153

6.Lee, 2007: P174

7. Lee, 2007: P153-154

8. Lee, 2007: P176-178

9. Lee, 2007: P178-179

10. Lee, 2007: P157-158

11. Lee, 2007: P179-181

12. Lee, 2007: P159

13. Lee, 2007: P161

14. Lee, 2007: P182-186

15. Lee, 2007: P186-187

16. Lee, 2007: P112

17. Lee, 2007: P106

18. Chang, 2003: P145-146

19. Lisa See, “‘Paper sons,’ hidden pasts”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

20. Chin, Thomas. “Paper Sons”. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

21. Lee, 2007: P1204

22. Duncan E. McKinlay, “Legal Aspects of the Chinese Question”. San Francisco Call. (23 November 1901), Retrieved 6 March 2018.

23. Lee, 2007: P192

24. The National Register of Historic Places (16 August 2007). “Celebrating Asian Heritage”. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

25. William Bright; Erwin Gustav Gudde (30 November 1998). 1500 California place names: their origin and meaning. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-520-21271-8. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

26. Chang, 2003: P148

27. Lee, 2007: P127

28. “United States Immigration Station (USIS) « Angel Island Conservancy”. angelisland.org. Archived from the original on 2014-09-16.

29. Howard Markel, Alexandra Stern. “Which face? Whose nation?: Immigration, public health, and the construction of disease at America’s ports and borders, 1891-1928”. The American Behavioral Scientist. 42 (9): 1314–1331.

30. Luigi Lucaccini. “The Public Health Service on Angel Island”. Public Health Reports. 111 (January/February 1996): 92–94.

31. Him Mark Lai and Genny Lim. “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940” (Naomi B. Pascal Editor’s Endowment) Nov 11, 2014

32. “美国天使岛上的华裔移民梦魇 经历奇耻大辱”中国新闻网. 2009. http://news.sohu.com/20090315/n262799197.shtml

33. Steve Kwok, “ My Father Was a Paper Son” https://www.aiisf.org/immigrant-voices/stories-by-author/737-my-father-was-a-paper-son/

34. Bruce Low, (1899). “Report upon the Progress and Diffusion of Bubonic Plague from 1879 to 1898”. Reports of the Medical Officer of the Privy Council and Local Government Board, Annual Report, 1898-99. London: Darling & Son, Ltd. on behalf of His Majesty’s Stationery Office: 199–258. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

35. Guenter B. Risse, (2012). Plague, fear, and politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 1421405539. OCLC 809317536.

36. Elliott Robert Barkan, (2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598842197. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

37. Lee, 2007: P125

38. Yunqiu Zhang “Chinese boycott of 1905” http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/421-chinese-boycott-of-1905.html

39. SIN-KIONG WONG “Die for the Boycott and Nation: Martyrdom and the 1905 Anti-American Movement in China”.Modern Asian Study. Volume 35, Issue 3 July 2001:P565-588

40. Chinese boycott of 1905 http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/421-chinese-boycott-of-1905.html

41. Chang, 2003: P142-144

42. Michael Hunt, The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and China to 1914 (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1983):234-41.

43. Guanhua Wang, “In Search of Justice: The 1905-1906 Chinese Anti-American Boycott” (Harvard East Asian Monographs)

44. Shih-Shan H Tsai, (1976). “Reaction to Exclusion: The Boycott of 1905 and the Chinese National Awakening”. Wiley.com.

45. Lee, 2007: P85

46. Lee, 2007: P126

47. B Tong, (2000). The Chinese Americans. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, P52-53.

48. 金开城主编,“孙中山与中国同盟会的建立”(吉林文史出版社)

49. 五洲洪门致公总堂 http://www.gheekungtong.org/about.html

50. 陈艳群。 孙中山先后六次赴檀岛累计七年。 世界新闻网北美华文新闻,华商资讯。 2011年6月8日上午06:00。

51. 陈艳群。 孙中山出生证件非伪造。 世界新闻网北美华文新闻,华商资讯。 2011年6月8日

52. 王起鹍:中国致公党卓越的创始人--黄三德。写在中国致公党成立90周年之际。http://www.hmyzg.com/2015-wqk/2015-qkw/2015-hsd.htm

53. 陈素敏:“洪门大佬”黄三德:一生写就《洪门革命史》

54. “革命派与改良派的大论战” 2009-12-22 13:28. http://t.m.youth.cn/transfer/index/url/agzy.youth.cn/xzzh/llzs/200912/t20091222_1118095.htm

55. 邹佩丛, ‘美洲中华革命军筹饷局 筹款情况研究” 一一以《美洲金山国民救济局 革命军筹饷征信录》为中心 http://jds.cssn.cn/webpic/web/jdsww/UploadFiles/ztsjk/2010/11/201011041428068204.pdf

56. Peter Kwong, Kusanka Miscevic. “Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Commiunity.”(the New Press, New York, London, 2005): P100-101.

Pingback: White Paper: National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – 美华史记