Sui Sin Far, a Biracial Chinese-English Female Writer in North America

Yuan Zhuang

Ancient sister, I reach backward to take your hand

— Author unknown

Edith Maude Eaton, whose pseudonym is Sui Sin Far (Cantonese transliteration of Narcissus), was a Chinese-English biracial female writer. Sui Sin Far’s career included the publication of numerous short stories, countless pieces of journalism, and one book. She may have been the earliest writer of American fiction to have Chinese ancestry.

Born in England in 1865 to a Chinese mother and British father, Sui Sin Far immigrated to eastern Canada as a child in 1873. She lived and worked in Montreal until she was nearly thirty-two years old, at which point she began a life of travel that intertwined with her work and writing. In 1897, she spent a brief interval in Jamaica, and in 1898, she began her travels in the United States, residing in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Boston over the next fifteen years. Her journeys were marked by intermittent crossings of the continent and the border back into Canada, culminating in her illness and death in Montreal in 1914.

Sui Sin Far was caught between warring cultures in an arena of racism, poverty, and sexual inequality. Writing from the Chinese American woman’s perspective as early as the 1890s, she committed to portraying the figure of the Chinese North American woman visibly and vocally. On Sui Sin Far’s printed page, Chinese American women were given a voice, allowing readers to hear them speak for themselves for the first time in North American literature. This occurred during what was, for Asians, an era of exclusion—a time during which Chinese and other Asian populations in North America occupied the lowest rungs of the ethnocultural pyramid, holding a legal status lower than that of African Americans or African Canadians. Sui Sin Far’s voice was not a militant one. She painted Chinese North Americans not as exotics, but as ordinary human beings trying to live normal lives. Her fiction sought not to exploit, but to record, explain, and give meaning to the experience of the Chinese in America. She forced readers to consider American literature and sentimentality from a place outside the white western consciousness. The tradition of North American writers of Asian descent began with Sui Sin Far; more specifically, she was the founder of the Chinese North American woman writer’s tradition. Sui Sin Far planted the seeds for major themes that have recurred in Chinese North American literature over the following centuries: exile and identity conflict, the oppression of Chinese by white society and of woman by man, etc.

In 1975, An Anthology of Asian American Writers recognized Sui Sin Far’s pioneering role in the development of Asian American literature. The phrase “Chinese American” may have originated with Sui Sin Far, when she wrote that her concern was with “those Chinese who came to live in this land, to make their home in America……Chinese Americans I call them”; Sui Sin Far is also credited as “one of the first to speak for an Asian-American sensibility that was neither Asian nor white American.” Sui Sin Far demonstrated what it meant to be the child of a biracial union in a racist society: rejected by both Asia and white America, the “Asian-American” held the ambivalent position of being a North American exile. Her aesthetic beliefs centered on a worldview of “one-family vision”, which posited “race” as a social construction—artificial, contrived, and divisive—and advanced a communitarian vision that respected cultural differences but dissolved social barriers based on race. This worldview insisted that nationality was no bar to friendship with those whose friendship was worthwhile, and that humans and other living beings must exist in harmony to survive. In other words, Sui Sin Far promoted an ultimate sense of human community transcending all contrived groupings. In this sense, Sui Sin Far’s aesthetic vision was far ahead of her time and has startling contemporary significance.

Only when the whole world becomes as one family will human beings be able to see clearly and hear distinctly.

——Sui Sin Far, “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian”

Her mother, Lotus Blossom (recorded in the United Kingdom and Canada as Grace A. Eaton), was born in China in 1846, four years after the Treaty of Nanking granted merchants, Christian missionaries, and military forces from Europe and North America a right to move into China at key ports—most importantly, Shanghai. Family legend holds that her home province was Guangdong. Her given name at birth is unknown, as she was stolen from her home—she was found in a circus somewhere in China after her adoptive parents, circus performers, had died. Lotus Blossom had been a tightrope dancer in her early youth. She was then taken from China to England as the protegée of Sir Hugh Matheson, who brought her up and gave her an English education.

In England, Lotus Blossom was educated at the Home and Colonial school, a training college for schoolmistresses. She trained to become a missionary. Upon returning to China, she may have lived in a mission station, a core element of the British cultural communities that, by the 1860s, had infiltrated China’s landscape.

Sui Sin Far’s father, Edward Eaton, was born in Macclesfield, England, in 1839—the same year England’s first war with China, commonly known as the Opium War, was launched in Hong Kong harbor. His father’s family held mercantile interests in the silk center of Macclesfield. Edward had inclinations toward art and studied in France, taking first prize at the Paris Salon. His “master” advised his father to encourage Edward’s growth as an artist, but his father instead sent Edward to the Port of Shanghai at the age of 22, where he set him up in business.

Sometime in the early 1860s, Lotus Blossom and Edward Eaton met and married. They were married by the British Consul and returned to England the following year.

Her father overturned family expectations and traditions, first by pursuing a career in art and then by marrying a Chinese woman—but it was his marriage that ultimately cut him off from his kindred. Sui Sin Far’s mother, a Chinese woman who would have remained home-bound while awaiting an arranged marriage if she had followed convention, was independent enough to travel and choose her own husband. The two stayed together all their lives and had 14 children. The decision made by these two people at this historical juncture profoundly affected their futures and those of their children to come, thereby altering the course of North American literary history. In this sense, they were mavericks, whose children had to decipher their own racial identities in the context of the European-dominated societies in which they found themselves.

The first of these children was Edward Charles, born in China in 1864. Sui Sin Far was next, the first child Lotus Blossom would give birth to in England: Edith Maude Eaton was born on March 15, 1865 in Upton Cottage, Parish of Prestbury, County of Chester, Macclesfield, England, a site she later described as “the birthplace of my father, grandfather, great-grandfather and … and …” In 1865 there was, statistically speaking, no Chinese population living in England.

Sui Sin Far would live in three countries for significant periods—England, Canada, and the United States. Sui Sin Far and her siblings were Christians and appeared European, but their experience points to the reality beneath the illusion: mere knowledge of their Chinese mother was sufficient to incite racist attacks wherever they lived. The stigma against the children was magnified because they symbolized their parents’ violation of cultural mores; furthermore, the Eatons’ very existence as a family offered a vision of cultural pluralism that none of the countries in which they lived was willing to accept.

She describes her mother as “English bred, with British ways and manners of dress.” A photo from this period portrays Lotus Blossom in a Victorian gown, with a bustle. Because her mother had been raised in England from an early age, this “costume” was not false but reflected who she was – or, at least, a part of who she was – as an Anglicized Chinese woman married to a British citizen. However, the Victorian bonnet did not mask her Chinese face. Due to the social construction of the divisive categories of race from such physical features as skin color, hair texture, and eyes, race remains identifiable across cultural and national changes.

“The day on which I first learned I was something different and apart from other children” is clearly articulated by the adult author through a particular incident during which she was “scarcely four years of age, walking in front of my nurse, in a green English lane, and listening to her tell another of her kind that my mother is Chinese.” “Oh, Lord!” the second nurse answered, turning the small Sui Sin Far around and examining her “curiously from head to foot”. In another episode, Sui Sin Far was playing with a girlfriend when a third girl, passing by, called: “I wouldn’t speak to Sui if I were you. Her mamma is Chinese.” Again, at a children’s party, she was “called from my play by the hostess for purposes of inspection” by “a white-haired old man” who “adjusts his eyeglasses” and exclaimed — “Ah, indeed! … now I see the difference between her and other children … very interesting little creature. What a peculiar coloring! Her mother’s eyes and hair and her father’s features, I presume.” Seeking to avoid the old man at the party, Sui Sin Far “[hid] myself behind a hall door, and refuse[d] to show myself until it is time to go home.” “The greatest temptation was in the thought of getting away, to where no mocking cries of ‘Chinese! Chinese!’ could reach,” She admitted years later. “Why? Why?” she would ask over a lifetime of inquiry, scrutinizing her mother and father: “Is she not every bit as good and dear as he?”

Through the eyes of childhood there is no difference in race, until society implants the division.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel “Pat and Pan”

Lotus Blossom and Edward migrated from England to settle permanently in Montreal, in eastern Canada, around 1872. To a family that had violated social taboos, perhaps North America’s size and heterogeneous population seemed more appealing than a small English village.

Though the Eatons would eventually settle in Montreal, Sui Sin Far recalls being in the United States first: “My parents have come to America. We are in Hudson City, New York, and we are very poor.” Here, she encountered Chinese people for the first time outside of her own family, when she and her brother Edward Charles passed a Chinese store — a long, low room with the door open. The children peeked in and saw two men: “uncouth specimens of their race, dressed in working blouses and pantaloons with queues hanging down their backs.” The little girl recoiled in shock. “Oh, Charlie … Are we like that?” she asked. “Well, we’re Chinese, and they’re Chinese, too, so we must be!” Charlie retorted with an eight-year-old’s logic.

Of course, these men differed from the Eaton children in many ways, including the ocean they had sailed across to arrive in North America, but they shared a common status as objects of the racist attitudes and actions of a European-dominated society. In North America, treatment went beyond the “curiosity” she had suffered in England to include physical violence. Attacks on the Eaton children by boys and girls on the streets of New York reflected the attitudes of adults in the country: “Chinky, Chinky, Chinaman, yellow-face, pig-tail, rat-eater,” a boy once taunted. “Better than you,” retorted her brother. “I’d rather be Chinese than anything else in the world,” Sui Sin Far shouted. And battles ensued. “They pull my hair, they tear my clothes, they scratch my face and all but lame my brother; but the white blood in our veins fights valiantly for the Chinese half of us,” she recollected.

The gold rushes and construction of railroads in the United States and Canada first brought Chinese immigrants to the western regions of these nations in the mid-nineteenth century. In 1885, completion of the transcontinental railroad in Canada led to the formation of a legitimate Chinese community in eastern Canada. The question of whether to import Chinese labor, and to what extent, had been an ongoing issue of national debate.

Upon their arrival in Montreal, the family took a sleigh from the train station to a little French-Canadian hotel, where Sui Sin Far’s father helped her mother out, and then, one-by-one, the little black-haired heads of the children emerged from beneath a buffalo robe. The sleigh was surrounded by villagers, whose curiosity, she writes, “is tempered with kindness as they murmur, ‘Chinoise, Chinoise.’ While older persons pause and gaze upon us, very much in the same way that I have seen people gaze upon strange animals in a menagerie.” Their new Canadian neighbors, both French and English, were alert to the family’s Chinese race.

The abuse the Eaton children suffered in Montreal more or less echoed their experience in New York. Other children refused to sit next to them at school, and when they went out, Sui Sin Far recalled, “our footsteps are dogged by a number of young French and English Canadians, who amuse themselves with speculations as to whether, we being Chinese, are susceptible to pinches and hairpulling.” Pitched battles again ensued, and the children would “seldom leave the house without being armed for conflict.”

Why are we what we are? I and my brothers and sisters. Why did God make us to be hooted and stared at?

——Sui Sin Far, “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian”

As Sui Sin Far reflected as an adult, her mother could not understand “the depths of the troubled waters through which her little children wade,” for Lotus Blossom was “Chinese,” as Edward was “English” – that is, “they know who they are.” In her painful struggle toward self-definition, she strove for a place in both worlds, but felt severed from both. “My mother’s people are as prejudiced as my father’s. I do not confide in my father and mother,” she wrote in her adult years. “They do not understand. How could they? He is English, she is Chinese, I am different to both of them —— a stranger, though their own child”.

At age 8, inspired by a particular teacher, Sui Sin Far “conceived the ambition to write a book about the half-Chinese.” Her years in England had taught her to assume an English identity, as any deviance from the norm was perceived as strange and unacceptably different. However, internally, she sought to define her own story. “Whenever I have the opportunity, I steal away to the library and read everything I can find on China and the Chinese”. But as the eldest daughter of a poor family with many children, she was obligated to take on the role of a second mother and assume responsibility for her siblings’ upbringing and care. Thus, Sui Sin Far was not free to pursue a life of her own until she was past thirty.

At one point, the Eaton children were homeschooled by their parents. As Sui Sin Far wrote in her diary at age 11: “I, now in my 11th year, entered into two lives, one devoted entirely to family concerns; the other, a withdrawn life of thought and musing. This withdrawn life of thought probably took the place of ordinary education with me. I had six keys to it; one, a great capacity for feelings; another, the key of imagination; third, the key of physical pain; fourth, the key of sympathy; fifth, the sense of being differentiated from the ordinary by the fact that I was an Eurasian; sixth, the impulse to create.”

By 1883, Sui Sin Far’s duties as the family’s eldest daughter had changed from “carrying out babies” at home and selling paintings and lace on the streets to joining the wave of women entering the traditionally male world of office work. In the mid-1880s, the introduction of typewriters, among other developments, opened the door to new careers for thousands of women. At age 18, she went to work at the Montreal Daily Star as a typesetter and taught herself shorthand in order to enter the occupation of stenography. She then obtained a position as a stenographer for a law firm in Montreal’s original riverfront business district.

Somewhere between the demands of family and employment, she somehow found time and space to write. In the mid-1880s, her first publications appeared – “humorous articles” in the radical U.S. newspapers Peck’s Sun, Texas Liftings, and the Detroit Free Press.

Sui Sin Far said “I intended to form all my characters upon the model of myself.”

Sui Sin Far’s work at this time indicates that her family and friends were actively pressuring her to look for a husband. In 1888-89, 6 short stories and 2 essays were published in a new periodical devoted to the promotion of Canada, the Dominion Illustrated; most emphasized the romantic adventures of European-Canadian women and contained the humorous, satirical barbs at romantic love and marriage that would become her hallmark. Each was signed, “Edith Eaton”.

Sometime in the early 1890s, a clergyman visited Lotus Blossom with the request that she call upon a young Chinese woman who had recently arrived from China as the bride of one of local merchants. Sui Sin Far accompanied her mother, thus initiating her transition from “outsider” to “insider” among the small but growing Chinese population in Eastern Canada. Several factors contributed to the rapid growth of the Montreal Chinese community in the last fifteen years of the century: the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, the U.S. passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, and Montreal’s assumption of the “entrepot” position in the distribution of Chinese labor to Europe and the Americas. For her, the clergyman’s call marked a new juncture in her life: “From that time I began to go among my mother’s people, and it did me a world of good to discover how akin I was to them.”

Once over that threshold, Sui Sin Far did not turn back. She opened “an office of my own” as a stenographer and typewriter in the center of Montreal’s financial district in 1894-95. Her career independence grew with and because of her deepening involvement with the Montreal Chinese.

As a freelance journalist, Sui Sin Far received “most of the local Chinese reporting” from local papers, and her dormant self-conception of “Eurasian-ness” began to stir. Publicly, she moved beyond her status as a sympathetic outsider by vocally championing the Chinese Canadians against a new onslaught of racist laws and practices. On September 21, 1896, a letter entitled “A plea for the Chinaman,” addressed “To the Editor of the Star” and signed “E.E.”, spoke out against a national petition to raise the head tax placed on Chinese immigrants. Many who marched in protest carried Sui Sin Far’s letter in their pockets. The letter was translated into Chinese and included Sui Sin Far’s picture. her pride in her new role as a defender of the Chinese Canadian population was evident: “I meet many Chinese persons, and when they get into trouble am often called upon to fight their battles in the papers. This I enjoy”. Just as in childhood, Sui Sin Far was fighting the battles of Chinese North American immigrants—but now, the site of the conflict was not in the streets, but in the papers. Through her “Chinese reporting”, Sui Sin Far entered a new arena, one in which she would later locate her fiction’s primary subject matter as she established her literary voice.

One does not gain happiness by making others unhappy; moreover, those who are well off have an obligation to help those who are not.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel “The Peacock Lantern”

By the mid-1890s, at approximately thirty years old, Sui Sin Far had already made the pivotal choice to adopt the pseudonym “Sui Sin Far,” highlighting her Chinese heritage. “Sui Sin Far” was likely not a pseudonym, but a term of address her mother had used from early childhood. As a child, Sui Sin Far’s Chinese heritage could be relegated to the world of imagination and tucked out of sight, but as an adult, her identity was necessarily confronted in action. Her commitment to the cause of the North American Chinese transcended national borders, as was indicated by the fact that her September 21, 1896 letter addressed both New York and Montreal; she also spoke of a Chinese man from New York who visited her Montreal office. In 1896, she visited New York’s Chinatown for 2 weeks, and her first “Chinese stories” appeared during that year—the first in the New York journal Fly Leaf, the next two in the Lotus, a Kansas City journal, and the other two in the Los Angeles Land of Sunshine. All were signed from Montreal by “Sui Seen Far.”

This passage from “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian” provides a clue about how Sui Sin Far’s family, the Eatons, reacted to her new visibility:

“You were walking with a Chinaman yesterday,” accuses an acquaintance.

“Yes, what of it?”

“You ought not to. It isn’t right.”

“Not right to walk with one of my own mother’s people? Oh, indeed!”

This may have been a real conversation between Sui Sin Far and a sibling; more likely, it was a composite of many discussions around Sui Sin Far’s choice to “walk” ideologically apart from her family. This was a choice at direct odds with those her siblings were making as, one by one during the 1890s, they married into and became absorbed by the white community. Sui Sin Far was the sole member of the Eaton progeny to acknowledge and seek out the Chinese roots they all shared.

In 1897, Sui Sin Far gave up her office in Montreal and accepted a position as a reporter for a newspaper in Jamaica.

Before departing for Jamaica, Sui Sin Far took a trip, presumably for temporary work, to “a little town away off on the north shore of a big lake,” situated generally in the “Middle West.” With “a transcontinental railway” running through the town, and a “population … in the main made up of working folks with strong prejudices against my mother’s countryman,” the setting became a microcosm of the dynamics between white and Chinese North America. There, she worked as a stenographer, and while she was dining one day with her employer and other business acquaintances, the conversation turned to the “cars full of Chinamen that past that morning by train.” Listening to her dinner companions remark, “I wouldn’t have one in my house,” and “I cannot reconcile myself to the thought that the Chinese are human like ourselves,” Sui Sin Far recalled that a “miserable, cowardly feeling” kept her “silent,” for she realized that if she spoke, “every person in the place will hear about it the next day.” Then, she lifted her eyes and addressed her employer: “The Chinese may have no souls, no expression on their faces, be altogether beyond the pale of civilization, but whatever they are, I want you to understand that I am – I am a Chinese.” Her employer apologized to her: “I know nothing whatever about the Chinese. It was pure prejudice.” Sui Sin Far “admired” his “moral courage,” yet she did not remain much longer in the little town. Living for what was probably the first time in a community that did not know her family, she marks this as a turning point in her lifelong struggle to integrate “Sui Sin Far” and “Miss Edith Eaton.” “Sui Sin Far” came to express her Chinese identity, as “Edith Eaton” expressed her English one. The writer’s growth at this stage was toward her mother’s culture, but not necessarily away from her father’s—she saw both names as integral parts of her identity. At this dinner table, she announced – and thus learned for herself – that in each was the other. Appropriately, then, the underlying theme we see from her first work to her last is that people are multi-faceted, and human experience and relationships turn on ambiguity.

Life is generally ambiguous, and those who believe in simple answers to its complexities are the real “strays”.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel “Who’s game”

How did a young Canadian woman find the opportunity to travel to Kingston, Jamaica—a six-day trip by railroad and steamship? Canada, a British dominion, supplied an ongoing stream of women workers to Jamaica, a British colony.

In British colonies like Jamaica, the racist attitudes of the dominant white population toward people with skin darker than the Anglos’ were similar to those Sui Sin Far knew as a child in Montreal. Anglo ethnocentrism was approaching new heights in the period leading up to the Boer War. She knew that the “colored” categorization, which was used in Jamaica to segregate mixed-race people of varying shades of “black-ness” from the privileged whites, could apply equally to Eurasians. She also recognized that she had to place herself in the “white” category in order to travel and work. If she were to be identified as the daughter of Lotus Blossom, she may not have been able to travel at all.

By 1898, Sui Sin Far was back in Montreal, recuperating from malaria. The same year, she began traveling on an advertising contract with a railway company, receiving train fare in return for writing railway ads, a common outlet for writers at the turn of the century. Her first destination was San Francisco. The editor of the San Francisco Bulletin assigned her no writing, but sent her to canvass Chinatown for potential new subscribers. There, she developed new contacts with the local Chinese community.

Though the “battles” fought by Chinese Americans in San Francisco paralleled those fought by Chinese Canadians in Montreal, Sui Sin Far found an older, larger, and more unified Chinatown community in San Francisco. The community had begun its process of growth 40 years earlier, serving as a rendezvous point for immigrants across the Pacific and throughout the United States, and contained a population ranging from 10,000 to 30,000, depending on the season. Here, she confronted prejudice against the Anglo side of her heritage, an ironic mirror image of the “invisible minority” status granted by her appearance. “Chinese merchants and people generally are inclined to regard me with suspicion,” she recollected, and “the Americanized Chinamen actually laugh in my face when I tell them that I am of their race”. Due to her own experiences, Sui Sin Far understood their reasons: “They have been imposed upon so many times by unscrupulous white people.” She also saw herself through Chinese American eyes as a pretender to their culture: “How … can I expect these people to accept me as their own countrywoman” when “save for a few phrases, I am unacquainted with my mother tongue?” But just as a Chinese immigrant woman had initiated her entrance into the Montreal Chinese community, Chinese American women served as Sui Sin Far’s guides to San Francisco’s Chinatown: “Some little women discover that I have Chinese hair, color of eyes and complexion, also I love rice and tea. This settles the matter for them – and for their husbands”. Sui Sin Far – at age 33 and on the opposite side of the continent from her Montreal family – appears to have acknowledged her Chinese ancestry openly, ceasing to see Chinese North Americans as an “other” in relation to whites. Her retrospective measure of this progress in “Leaves” implies a newfound affinity for Chinese North Americans as individuals, including the “Chinaman” inside herself: “My Chinese instincts develop. I am no longer the little girl who shrunk against my brother at the first sight of a Chinaman. Many and many a time, when alone in a strange place, has the appearance of even a humble laundryman given me a sense of protection and made me feel quite at home.”

Sui Sin Far moved back and forth across the border between Canada and the United States many times during an era in which the Geary Act of 1892 (which extended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 for 10 years) made it illegal for her, as a person of Chinese descent, to enter the United States. That she was able to manage border crossings without any difficulty suggests her English name and appearance masked her Chinese heritage, a fact she was forced to exploit whenever she crossed national borders. Her experience was that of a woman persecuted because of her race, forced by society into assuming a chameleonic identity, and compelled to play roles to survive under the perpetual tension of the threat of exposure.

The very fact that she had to hide her true identity indicates the depths of the racism of the time. Being caught in this dilemma herself presumably reinforced Sui Sin Far’s empathy with people of color and helped her identify with the plight of Chinese immigrants on America’s West Coast. Crossing national borders undoubtedly developed her awareness of the conditions of exile and betrayal, disguise and deceit, that she would address thematically in her short stories.

What is considered “right” by those in authority at every social level can often be wrong. Complete obedience to authority is absurd, and one must always temper it with individual judgment.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel “The Inferior Man” and “Ku Yum and the Butterflies”

The condition of being an exile in a strange land was a central idea for Sui Sin Far. She might have felt like an exile in her own family on multiple levels: as the only daughter who chose not to marry, and as the only sibling who directly sought out her Chinese heritage. In Canada, she was an exile from England, and in the United States she was an exile from Canada. The question of which place to call home certainly posed a dilemma.

Like many Canadian writers at the turn of the century, Sui Sin Far came to the United States to earn a living and find publishing outlets. The irrelevance of nationalism to Sui Sin Far herself, as a child of two races and four countries, was clearly articulated: “I have no nationality, and am not anxious to claim any.”

The humanistic vision later repeated throughout Sui Sin Far’s short fiction was as follows: “What does it matter whether a man be a Chinaman, an Irishman, an Englishman or an American. Individualism is more than nationality……”

Love is stronger than hate and artificially contrived social borders.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel ” The Banishment of Ming and Mai “

The question of race assumed additional importance in the lives of Sui Sin Far and her sisters in their choices regarding marriage. Her own parentage was no doubt a root cause of her choice not to wed and have children. Making this choice meant defying the expectations society laid down for her in the nineteenth century and accepting the consequences of social disapproval. (Sui Sin Far might not have been the only Eaton sister seeking alternative options to marriage—her two sisters both entered Catholic nunneries briefly, but later married white men.)

In 1880 the California state legislature had expanded its previous anti-miscegenation law, which prohibited marriage between white and “Negroes or mulattoes,” to include the category deemed “Mongolian.” In 1905, the state declared such marriages illegal and void. The racist environment marked by such laws provided the context for a story in “Leaves” about an Eurasian who “allowed herself to become engaged to a white man after refusing him nine times. She had discouraged him in every way possible, had warned him that she was half Chinese; that her people were poor, that … she sent home a certain amount of her earnings, and that the man she married would have to do so much … that she did not love him and never would.” Because the young man swore none of this mattered (“he loved her”) and “because the young woman had a married mother and married sisters, who were always picking at her and gossiping over her independent manner of living, she finally consented to marry him, recording … in her diary thus: ‘I have promised to become the wife … because the world is so cruel and sneering to a single woman – and for no other reason’”. Provoking her fiancé about her Chineseness, the woman tells him that when they are married, she will give constant parties, filling their house with Chinese “laundrymen and vegetable farmers”; in response, the young man suggests that when they are married, it would be nice if “we allowed it to be presumed that you were – er – Japanese?” The young woman breaks the engagement and that evening, writes in her diary—words that reflect the pulse of Sui Sin Far’s own strike toward liberation— “Joy, oh, joy! I’m free once more. Never again shall I be untrue to my own heart. Never again will I allow anyone to ‘hound’ or ‘sneer’ me into matrimony”.

To quote S.E. Solberg, a writer and scholar of Asian American literature, “The Chinese were commonly perceived as mysterious, evil, nearby, and threatening, while the Japanese were exotic, quaint, delicate … and distant … the general fascination with the exotic (Japanese) was able to transcend racist ideas so long as distance was a part of the formula.”

Sui Sin Far’s younger sister Winfred, also an author, chose to mask her Chinese identity by writing under the alias “Onoto Watanna” and feigning a Japanese heritage. Her first book was published earlier than her older sister, and her career was ostensibly more successful, but she privately hinted that Sui Sin Far possessed more talent, a judgment corroborated explicitly by Sui Sin Far’s editor.

Passages in Sui Sin Far’s prose illustrate the fact that she considered marriage with men from either side of her heritage and elucidate her decision to become a ‘serious and soberminded spinster”. From her experiences with Chinese Canadian and Chinese American men, she concluded that full-blooded Chinese people carried a prejudice against the half-white. The short story “Sweet Sin” follows an Eurasian protagonist who cries out against the double-bind in which Sui Sin Far was caught: “But, Father, though I cannot marry a Chinaman, who would despise me for being an American, I will not marry as American, for the Americans have made me feel so I will save the children of the man I love from being called ‘Chinese! Chinese!’”

In 1898, she published two more stories in Land of Sunshine, then another two in the same publication in 1899, plus one in the Overland Monthly. She recalled that “latent ambition aroused itself. I recommenced writing Chinese stories.” Land of Sunshine remained the main outlet for her work.

The summer of 1899 marked her first trip to southern California. She visited many sites, such as Los Angeles and San Diego. Her bonds with her family nevertheless remained intensely close. “I have to come home and see them all because I got so lonesome. I am always coming home and going away.” From the end of July until mid-October of 1900, Sui Sin Far stayed in Montreal. During this stay, she had two more stories published in the Chicago Evening Post.

By the fall of 1900, Sui Sin Far had left Montreal for Seattle, where she worked in a lawyer’s office as a legal stenographer. Among all of Sui Sin Far’s various landing points in her search to find work, Seattle was the closest to permanent, a city where she would live on and off for the first decade of the twentieth century. The Chinese American community in Seattle was close in size to Montreal’s, numbering 438 in 1900, the year after Sui Sin Far arrived, and grew to 924 by 1910. She reminisced: “I taught in a Chinese mission school … and learned more from my scholars than ever I could impart to them”; “I managed to hold up my head and worked intermittently and happily at my Chinese stories”. In a series for the Westerner, published in Earlington, Washington, in the summer of 1909, she portrayed the experiences of West Coast Chinese Americans with an intimacy of voice that implied that she mingled freely among them. During this period, she gradually formed her worldview of “one-family vision,” which would become the central ideal advanced in her fiction. She clearly expressed the purpose of her “Chinese” fiction in 1904: “to depict as well as I can what I know and see about the Chinese people in America.” She pointed out that differences in manners do not belie differences in human substance: “Chinese Americans hide the passions of their hearts under quiet and peaceful demeanors; but because a man is indisposed to show his feelings is no proof that he has none.” It was an approach that boldly distinguished her from her contemporaries: “I have read many clever and interesting Chinese stories written by American writers, but they all seem to me to stand afar off from the Chinaman – in most cases treating him as a joke.” The mainstream writers not only treated Chinese and Chinese American characters as “jokes” but also used literature to legitimize racism, segregation, exclusion, and imperialism. Sui’s editors recognized that she was doing something different. In 1900, they observed: “to others the alien Celestial is at best mere literary material; in Sui’s stories he or she is a human being.”

I speak from experience, because I know the Chinaman in all characters, merchants, laundrymen, laborers, servants, smugglers and smuggled, also as Sunday School scholars and gamblers. They have faults, but they also have virtues. They think and act just as the white man does, according to the impulses that control them…… and are kind, affectionate, cruel or selfish, as the case may be.

——Sui Sin Far, “A Plea for the Chinaman”, “The Chinese in America”

During October and November of 1903, the Los Angeles Express printed a series of articles with Sui Sin Far’s byline. Bearing titles such as “Chinatown Needs a School” and “Chinese Laundry Checking”, the articles focused on Los Angeles’s Chinatown community of more than 5 thousand people. Sui Sin Far’s frank and detailed efforts “to depict … what I know and see” were successful, and these pieces were among the few by Sui Sin Far to be found in the markets. In 1900 she had 4 stories published, then 3 more between 1903 and 1905, in addition to her newspaper work.

On January 21, 1909, with the appearance of “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian” in the Independent, the author began to work biographically, revealing the painful past that shaped the stance and voice of the writer who now signed her name, “Sui Sin Far”. Her voice came bursting forth – publicly, nationally – bringing her unprecedented recognition and galvanizing a fresh wave of writing and publishing. Though the autobiographical essay was published in New York, Sui Sin Far was likely in Seattle at the time, as evidenced by a series of articles on “The Chinese in America” for a northwest paper called the Westerner which ran from May through August 1909. The series dealt with the ambiguities of “Americanization” faced by Chinese Americans and the problems of Chinese immigrants in their confrontation with whites. Such themes would dominate the last stage of her fiction.

Shortly after the last piece in this series, she moved from the West to Boston. In 1910, she published 9 pieces of short fiction in publications ranging from the Independent to Good Housekeeping containing Chinese American content and themes, which revealed a command of literary irony and signaled her artistic maturity. A composure and confidence emerged in the writer’s voice that had never before been present. In a Boston Globe article, Sui Sin Far stated that she moved to Boston “with the intention of publishing a book and planting a few Eurasian thoughts in Western literature.”

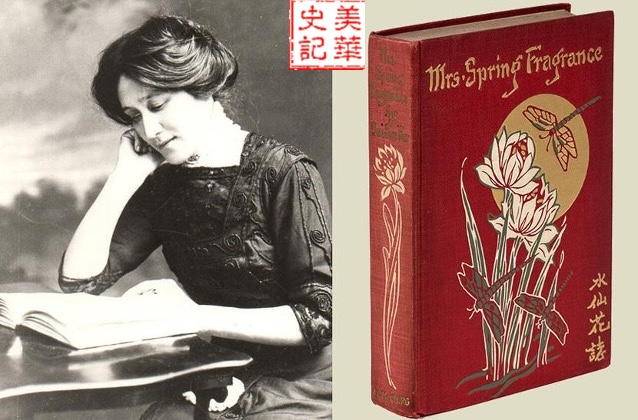

In June of 1912, two months after Sui’s 47th birthday, A. C. McClurg of Chicago published twenty-five hundred copies of Mrs. Spring Fragrance – a collection of Sui Sin Far’s short stories. Conceived in early childhood but completed nearly half a century later, the book contains 37 short stories, some of which had been previously published in magazines. Mrs. Spring Fragrance was recognized in reviews on both sides of the Canadian-U.S. border. The first appeared in the Montreal Daily Witness on June 22, 1912: “One of the charming gift books of the season comes from the pen of a Canadian Chinese, or half Chinese, woman, whose sympathies range her on the side of the Chinese mother rather than of the British father.” The second review, on June 29, 1912 in the Boston Globe, stated, “The tales are told with a sympathy that strikes straight to one’s heart; to say they are convincing is weak praise, and they show the Chinese with feelings absolutely indistinguishable from those of white people—-only the Chinese seen to have more delicate sensibilities, and more acute methods of handling their problems.” On July 7, 1912, the New York Times Book Review devoted one long, substantial paragraph to the book. The Times review was most astute in observing the unique interracial dialogue opened up by Sui Sin Far’s work and its broader significance to literature: “Miss Eaton has struck a new note in American fiction. The thing she has tried to do is to portray for readers of the white race the lives, feelings, sentiments of the Americanized Chinese of the pacific Coast, of those who have intermarried with them and of the children who have spring from such unions.” The Independent, August 15, 1912, commented, “the conflict between occidental and oriental ideals and the hardships of the American immigration laws furnish the theme for most of the tales and the reader is not only interested but has his mind widened by becoming acquainted with novel points of view.”

My stories and articles accomplish more the object of my life, which is not so much to put a Chinese name into American literature, as to break down prejudice, and to cause the American heart to soften and the American mind to broaden towards the Chinese people now living in America——the humble, kindly moral, unassuming Chinese people of America.

——Sui Sin Far, letter to the editor of the “Westerner”, November 1909

Between 1910 and 1912, New England Magazine printed 5 stories signed, “Sui Sin Far”. In terms of craft and maturity of vision, the New England Magazine stories are among Sui’s very best work. In 1913, the Independent published Sui Sin Far’s “Chinese Workmen in America”, an interesting counterpoint to “The Chinese Woman in America” published in 1897. Sui Sin Far’s aesthetic position in her career’s final phase is marked by her reaction to the dominant culture’s monolithic voice: a North American mainstream that claimed to speak for all of its people, but in reality spoke only for those of a European-based culture. Sui Sin Far created an environment, through the printed word, where various cultural voices could speak together and replace a uniform vision of social reality with a climate of pluralism. That multitudinous cultural voice speaking without privilege—in contrast to one voice dominating all others—is the goal toward which the world’s peoples must strive.

No one has the right to define a single “correct” perspective. Moreover, both show the dire results, cultural and individual, when a particular society decides to set itself up with only one perspective.

——The Moral of Sui Sin Far’s Novel “In the Land of the Free” and “The Sugar Cane Baby”

Years prior, Sui Sin Far had suffered from inflammatory rheumatism, leading to permanent heart trouble. She decided to leave Boston to reside once again in Montreal, where she sought treatment at the Royal Victoria Hospital and died suddenly at dawn on April 7th, 1914. She was in the midst of work on a long novel, and planning and writing shorter stories to meet the demand…

Words from “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian” connecting her ill health with her lifelong fight against racism seem to foreshadow her passing: “I had no organic disease, but the strength of my feelings seems to take from me the strength of my body … The doctor says that my heart is unusually large; but in the light of the present (1909) I know that the cross of the Eurasian bore too heavily upon my childish shoulders”.

Sui Sin Far was buried in the Eaton family plot in the “English” section of Montreal’s Mont Royal Cemetery. A monument marks her grave in commemoration of the work she did for her mother’s people. There are four large Chinese characters on the top of the monument that roughly translate ——“It is right and good that we should remember China”. Below is a line of small English characters —— ” Erected by her Chinese friends in grateful memory of… ” Then, English letters spell out both of her names—— “Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton” … There is no clear answer concerning when and by whom the monument, 4 feet in height and 18 inches across, was erected. Standing conspicuously above shorter stones, this simple gray granite monument is engraved in a white so bright it looks as if it were painted just yesterday.

References:

Annette White-Parks, Sui Sin Far/Edith Maude Eaton: A Literary Biography, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1995.