– The Home of Hundreds Chinese Immigrants in 18xx

Fan Jiao

Antioch, once called Marsh’s Landing, situated as the gateway to the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, ranks as the fifty-fifth largest city in California, boasting a population of 115,277. It was on July 4, 1851, that the town new minister, Rev. William Smith, inspired from the ancient biblical city of Antioch as known as “Cradle of Christianity”, located in what is now modern-day Turkey, successfully convinced its residents to rename the town Antioch.

In approximately 1859, coal deposits were unearthed in multiple locations within the hills to the south of Antioch. This discovery led to the establishment of coal mining as the primary non-agricultural industry for the residents of this community, marking a significant economic development alongside traditional farming and dairy activities.

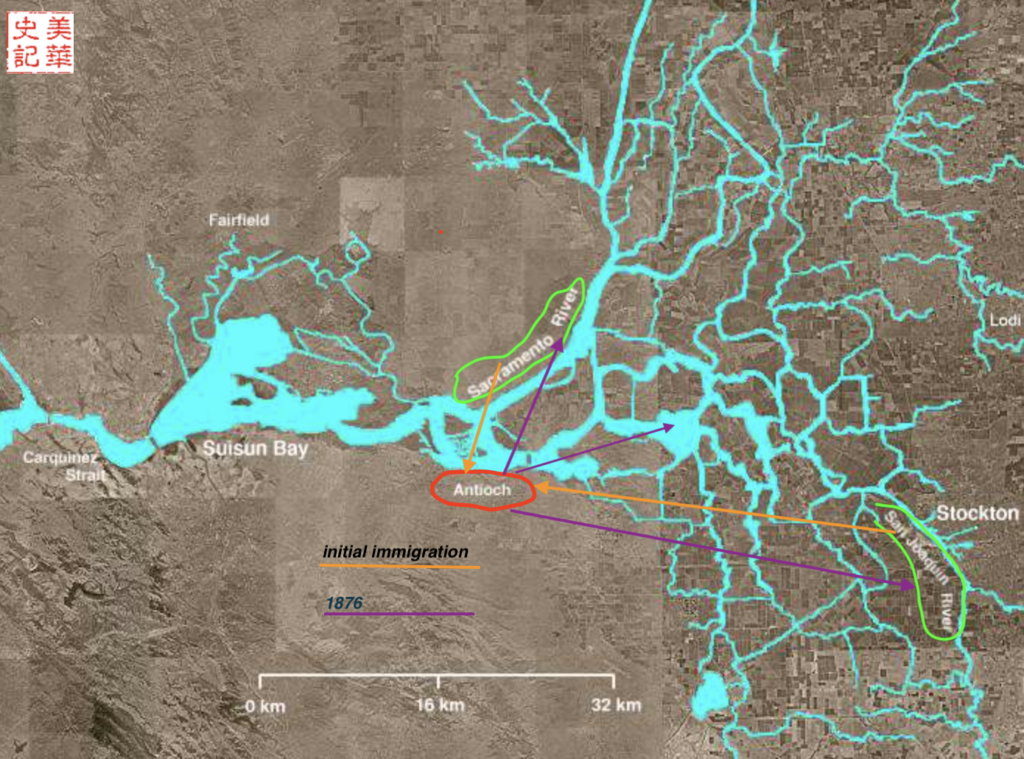

The earliest Chinese immigrants to Antioch were laborers recruited for various projects, including the construction of the transcontinental railway (1863-1869), levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta (1860-1880), coal mining, and canneries within the town. Between 1860 and 1890, an estimated 100 to 200 of these individuals resided in this pivotal city, facing forced segregation. Tragically, on April 30, 1876, a devastating fire set by white residents, destroyed Chinatown, prompting most of the Chinese population to depart Antioch by boat to Stockton, other Delta towns or San Francisco.

1. The Sundown town, Antioch

In the United States, before the mid-20th century, Sundown towns were predominantly white municipalities or neighborhoods that enforced racial segregation by excluding non-white individuals through various discriminatory local laws. Between 1851 and at least 1876, Antioch implemented a sundown ordinance, prohibiting Chinese residents from appearing in public after dark.[1]

In April 1876, escalating tensions between white residents and Chinese immigrants reached a boiling point. On 4/29, Newspaper reports from that period indicated that some young white men had contracted diseases from Chinese prostitutes. Fueled by anger, citizens demanded the departure of the Chinese from town by 3pm next day, leading to the immigrants leaving via boats bound for the Delta, Stockton, or San Francisco. However, this action did not satisfy the anger of the populace, as they proceeded to set fire to the entire Chinatown.

“Today the remaining houses have been removed and Antioch is now free from this degraded class,” the Los Angeles Evening Express said on May 2, 1876.

The sole notable dissent against the violence in Antioch came from San Francisco’s renowned Emperor Norton, although his objection was also influenced by economic considerations.

“The Antioch riot is a disgrace to Americans,” he wrote in an Oakland Tribune op-ed. “Now, therefore, We, Norton I., Dia Gracias Emperor, do hereby command the Grand Jury of Contra Costa County to indict the anti-Chinese leaders and have them brought to justice, and thereby protect the Americans and other foreigners and commerce in China.”[2]

2. Mayor Lamar A. Thorpe

Mayor Thorpe is of Black descent and was raised by a Mexican American family in East Los Angeles, making racial injustice deeply personal to him. Nearly ten years ago, during a city driving tour, former Mayor Don Freitas provided him with a history lesson about the Chinese residents of the past as they drove past Waldie Plaza, a downtown public square that once marked the boundaries of the old Chinatown. Thorpe, who often calls himself as “Blaxican,” pondered why the city, which boasts a racial diversity of about 110,000 residents—33% Latino, 28% white, 22% Black, and 12% Asian—did not openly discuss its past more.

Amidst ongoing attacks targeting Asian Americans and the tragic shooting incident that claimed the lives of six Asian women at spas in the Atlanta area and the killing of George Floyd in 2021, Thorpe concluded that it was imperative to confront Antioch’s history of violence and discrimination against Chinese immigrants.

On August 6, 2021, Mayor Lamar A. Thorpe issued a formal apology, 145 years after the burning of Antioch’s Chinatown by white residents, marking the city as the first in all of California to do so.[3]

A month later, on September 2`, 2021, the 3rd largest city in the state of California, City of San Jose, formerly apologized to Chinese descents for the burning down five Chinatowns by Whites in 1800s in San Jose.[4]

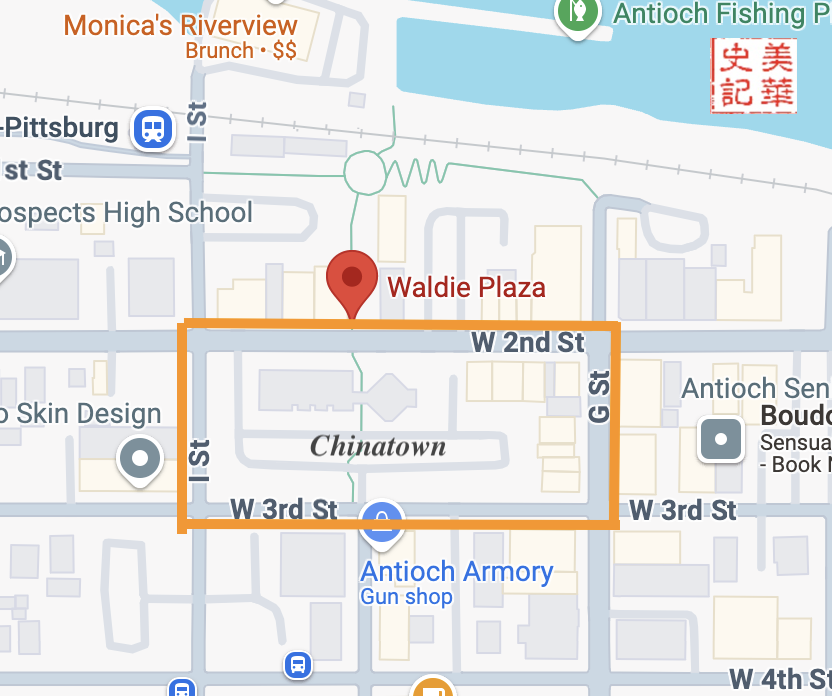

3. Antioch Chinatown

Chinese immigrants contributed to various sectors of Antioch’s economy, including local canneries, farms, levee construction, and coal mines. They played a vital role in building river levees and established a Chinatown in the area where the city’s downtown now exists.

The Chinatown was in 2nd and 3rd Street between G and I street. The main Chinese shops were in Waldie Plaza.

3.1 Antioch Chinese

Alfred Chan

Alongside his grandparents, Alfred Chan’s father was compelled to leave his hometown at that time. Chan was a veteran of World War II who served in the U.S. Navy and dedicated 38 years to working for the city of Oakland.

In 1939, after attending the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, Alfred Chan and his friends were on their way back home to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Feeling hungry during their journey, they decided to stop in Antioch, where Alfred once called home, for a meal. Recounted by his son Ron Chan, upon arrival, the waitress refused to serve the young men or even engage with them. An hour later, feeling both hungry and humiliated, they left the establishment.

Eighty-two years later, in November 2022, Alfred Chan received a heartfelt apology from Antioch Mayor Lamar Thorpe for the incident. Sadly, Alfred passed away at the age of 98, about three months after received the letter. Ron believed it brought closure to a painful moment in his father’s life. “An apology may only consist of words and may not fully resolve all past issues. However, without that initial step, there can be no progress,” remarked Ron Chan. [5]

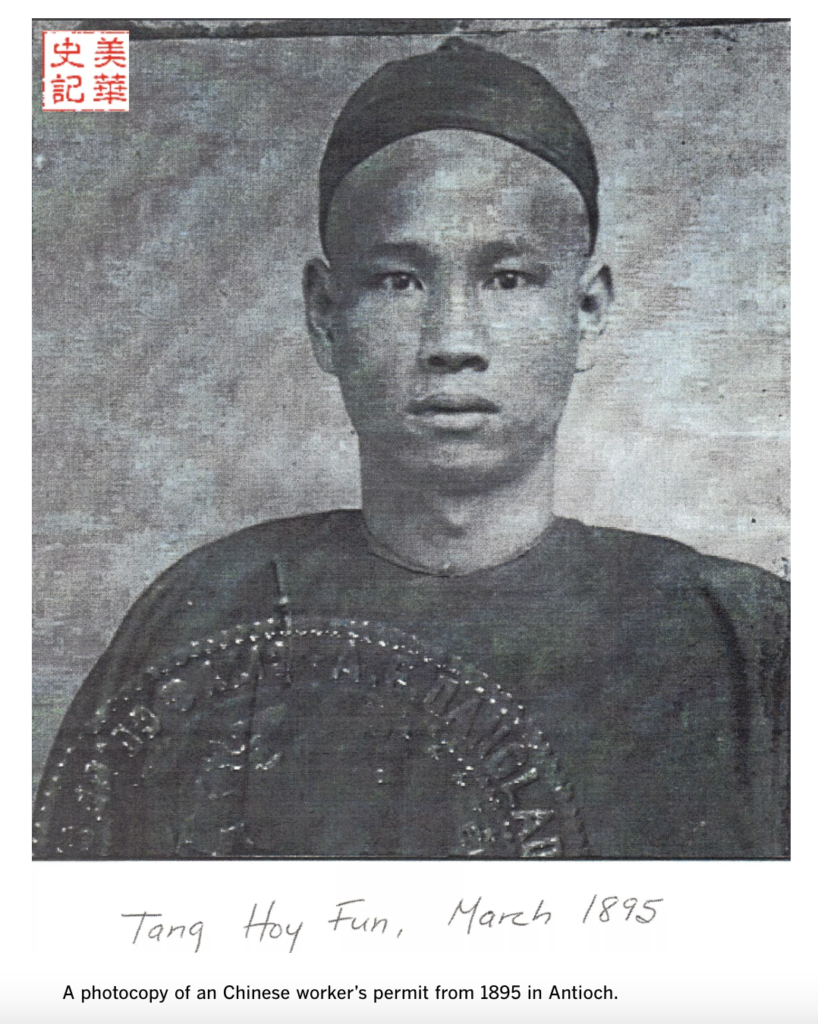

Tang Hoy Fun

Lew Hing, West Shore Canning Company

The West Shore Canning Company owned by Lew Hing operated in Antioch from 1920 to 1931 in cooperation with the American company The Robert Hickmott Company (with a 60/40 ownership split). Situated at the river’s end on “B” Street, the cannery primarily focused on fruit canning. After the Hickmott Company’s canning season concluded, the property was leased to independently produce fruit canned goods. [6]

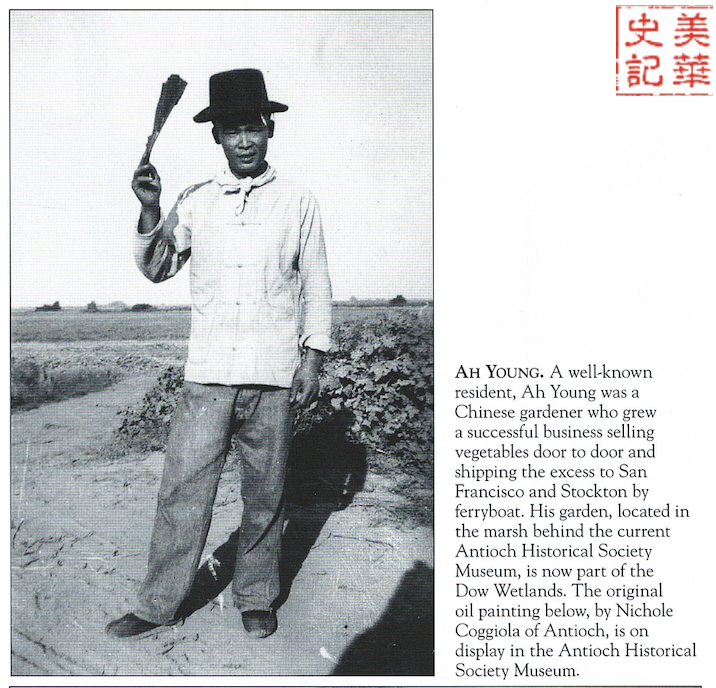

Ah Young

Residents of Antioch have warm memories of Ah Young, a Chinese farmer known as a “gardener,” who ran a thriving business during the 1920s by cultivating and selling vegetables directly to households. He also shipped surplus produce to San Francisco and Stockton via ferryboat. His vegetable “garden,” situated in the marsh behind the present-day Antioch Historical Society Museum, is now integrated into the Dow Wetlands Preserve.

4. Conclusion

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing and a surge in anti-Asian hate crimes amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Antioch takes the lead as the first city to issue a formal apology. Mayor Lamar Thorpe, who led the initiative, expressed, “Watching the news was agonizing, and I couldn’t help but feel that merely expressing solidarity with different groups isn’t sufficient.” He emphasized the need for tangible action alongside words. [3]

Absolutely.

It’s crucial that Asian Americans take concrete actions to ensure that any recurrence of discriminatory acts against our community is prevented for future generations.

Reference:

- Sundown towns in California, accessed on 4/10/2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Sundown_towns_in_California

- The Emperor Norton Trust, accessed on 4/10/2024, https://emperornortontrust.org/blog/2019/1/4/campaign-discovers-newspaper-record-of-emperor-nortons-famous-stand-off-with-an-anti-chinese-crowd

- Antioch Council officially apologizes for racism against Chinese immigrants in 1870’s, makes national news, PUBLISHER, MAY 22, 2021, accessed on 4/10/2024, https://contracostaherald.com/antioch-council-officially-apologizes-for-racism-against-chinese-immigrants-in-1870s-makes-national-news/

- 4. Historical Record of Chinese Americans | The Vicissitudes of Life in San Jose Chinatowns – Inheritance & Future, Fan Jiao, September 20, 2022, last accessed on 4/10/2024, https://usdandelion.com/archives/7679

- 5. A California city wrestles with its history of discrimination against early Chinese immigrants, Terry Tang and Deepa Bharath, AP, March 19, 2024, 8:05 AM ET, accessed on 4/10/2024, https://abcnews.go.com/amp/US/wireStory/antioch-city-complex-anti-asian-history-takes-meaningful-108269092

- The Antioch Herald, accessed on 4/10/2024, https://antiochherald.com/2021/05/antioch-historical-society-honors-may-as-asian-american-and-pacific-islander-heritage-month-with-history-lesson/