Author: Xin Su

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

San Francisco’s Chinatown was founded around 1850. Largely due to the 1849 gold rush, the Chinese population grew quickly in the city and soon the town became the largest Chinatown in the US. From the beginning, Chinatown had been under constant pressure to relocate. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, residents of San Francisco initially forbade Chinese people from rebuilding their town in an effort to force the Chinese to relocate to unlivable places. In spite of the immense racial tensions, the Chinatown community was able to unite and mobilize to solve the resettlement problem that helped prevent the forcible removal of the Chinese from their American homes.

Quote: The first private residence in San Francisco (called Yerba Buena by the Mexicans at the time) was an adobe house built by British sailor William Richardson around 1822. It was located in the modern-day Portsmouth square, which was the center of Chinatown. The second building, constructed in 1836, belonged to Jacob P. Lee, and it was located at the intersection of Dupont and Clay Street. It was built in 1836. At the time, Dupont Street was called the street of founding, and later it was renamed Grant Avenue. Soon after, Richardson built another house on Dupont Street West in 1838. On July 7, 1846, during the Mexican-American War, John D. Sloat declared California a US territory. Two days later, Captain John B. Montgomery led 70 soldiers and raised the American flag at Garden Corner Square. At that time, a few houses were built around the square, and it became the prototype of San Francisco [1, 2]. In 1849, news of the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill broke out, and a large number of gold prospectors flocked to San Francisco. San Francisco became the largest city on the West Coast at the time, a paradise for adventurers and a port of entry for the Chinese. From 1850 to 1900, San Francisco welcomed thousands of impoverished immigrants from southern China. During this period, Chinese merchants began to open shops and enterprises, and formed a Chinatown where Chinese people lived. Until the 1940s, most Chinese immigrants in San Francisco lived in Chinatown. The early days of Chinatown were full of loneliness, helplessness and pain.

California Earthquake

On Wednesday, April 18, 1906, at 5:12 in the morning, an unprecedented disaster struck a sleeping San Francisco. An 8.3 magnitude earthquake lasting 47 seconds caused the ground formation to move 10 feet horizontally and 3 feet up and down along the 300-mile section of the San Andreas fault [3]. The earthquake destroyed about 5,000 houses. Most of these collapsed houses were built on the dry marshes by the bay, and the construction quality was very poor. The earthquake caused serious damage, such as the collapse of chimneys, cracked windows, and damaged exterior walls and roofs. Subsequently, the surviving buildings were also destroyed by fires caused by the rupture of underground gas pipes [4,5].

The first fire after the earthquake resulted from a disastrous cooking incident on 395 Hayes Street. The earthquake had damaged the city’s water supply pipes, so there was no water to extinguish the fire, which went out of control and burned several streets at once [6, 7]. To make matters worse, the city’s firefighting chief (Dennis T. Sullivan, 1852-1906) had been seriously injured in the earthquake and died in the hospital four days later. Therefore, the firefighting operations lacked professional supervision. The mayor Eugene Schmitz and General Funston of San Francisco believed that in order to control the fire to the south of Market Street and to prevent it from spreading to Kearny Street, an isolated passage must be opened by blasting. At about 5 pm, General Funston ordered the house on the edge of Chinatown to be blown up. The blasting operation mistakenly used black powder (gunpowder) instead of dynamite. The first detonation ignited the wooden buildings in Chinatown at the end of Kearny Street, and the fire spread to Portsmouth square under the mountain and burned all the way to Montgomery Street. Before night fell, all of Chinatown was caught in a raging fire. [6, 7]

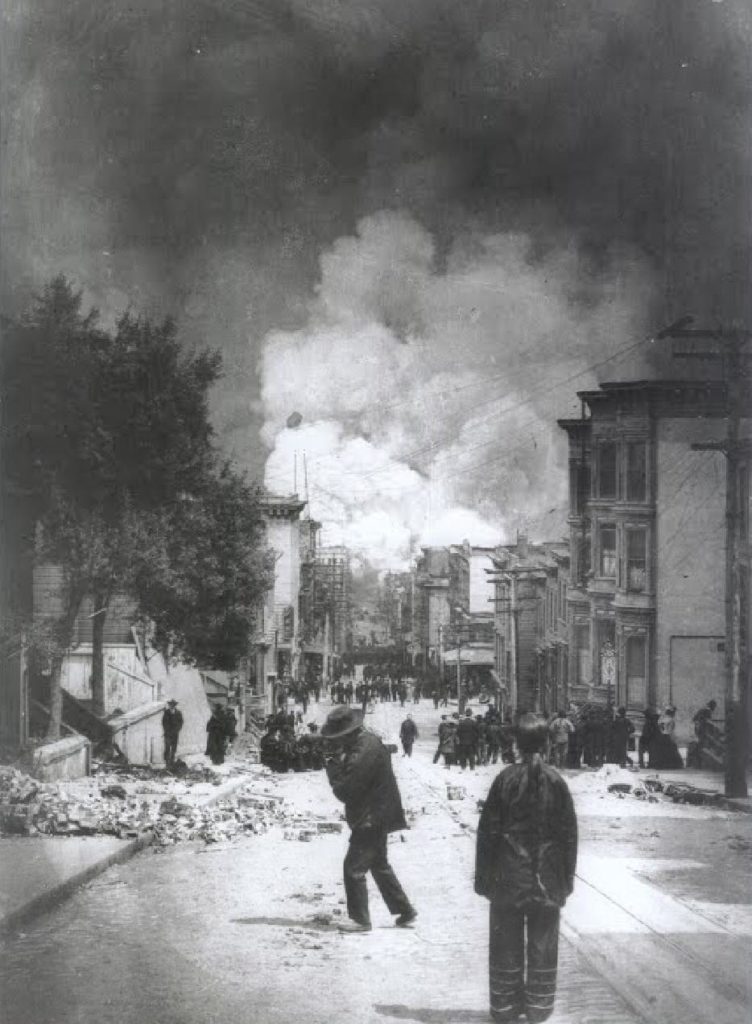

Picture 1: Chinatown in the fire after the earthquake. Photo taken

At the start of the fire, many residents refused to leave the city, including those living in Chinatown. After the fire spread, people began to flee for their lives, crowding the narrow streets of Chinatown like a colony of ants. On the day of the fire, more than 10,000 Chinese men carried their wives and ran for their lives in terror[6]. In the middle of the night, the fire in Chinatown grew larger and more terrifying, and the red flames illuminated the sky. Thick smoke covered the sky, which spanned thousands of feet. Packing only the necessities, people fled Chinatown, glancing back at their homes caught in the boundless fire as they ran. The fire raged all night [6].

The next day, the flames continued to roar through the city, straight through California Street (Sacramento Street), and returned to a decimated Chinatown, which had turned into rubble and ashes [6]. During this time, people began trying to rescue the western half of the city. For two days, San Francisco firefighters continued to fight without rest. The neighboring city of Oakland sent a fire brigade to help, pumping thousands of gallons of water from the bay to put out the fire. Three days later, the Navy joined the fire fighting, and the fleet sprayed water towards the burning city. Fortunately, a strong wind blew the fire in the direction of the ruins of the city, which somewhat improved the efficiency of fire fighting. At 7:15 in the morning on April 21, the 74-hour fire was finally extinguished. In the end, the fire destroyed 28,000 buildings and cost 500 million dollars in damages. [5, 6]

After the disaster, at least half of the San Francisco population became homeless and had to make shelters out of tents. The exact number of deaths is unclear. The official report mentions 478 deaths, but this number may be seriously underestimated. Gladys Hansen, an employee at the San Francisco Public Library, compiled a list of those who died, which listed more than 3,000 deaths [5, 8]. There is no doubt that there were quite a few Chinese among them. Some were trapped in houses and died in the fire. After the earthquake, 250,000 people were left homeless[6].

Within a few days after the fire broke out, the government set up 26 earthquake shelters and tent camps for the refugees to live in temporarily. Because the white did not want to live with the Chinese, the Chinese refugees moved from one temporary camp to another, rushing back and forth in the aftermath of disaster. Valuables were buried under the rubble of the burnt-down block of Chinatown, and the army that was sent to assist the displaced Chinese community did not sufficiently protect Chinese property. Not only that, but because “the Chinese smell bad”, they were forced to move three times to different makeshift shelters [9, 10].

Most of the survivors living in San Francisco’s Chinatown fled to the pier, crowded in lines to flee to the nearby Oakland Chinatown refuge [9]. Oakland was not equipped for the sudden influx of refugees. The situation became even worse for the Chinese who fled. They stayed in an open area on the shore of Lake Merritt, and when it started to rain after the fire, the shelterless refugees stood out in the open, drenched in the cold. Fortunately, merchant Lew Hing came to their rescue. He owned a two-block cannery in Oakland which was freed up as an asylum for Chinese refugees. There, they were given temporary housing and emergency supplies. His chefs prepared hot Cantonese dishes for the hungry. The exhausted Chinese were finally safe. [11]

Picture 2: Lew Hing was born in Guangzhou in 1858, and his brother moved to San Francisco and worked in a metal shop. One year after arriving in San Francisco, his brother died at age 13. When Lew Hing was 18, he opened a cannery with his business partner Lew Yu-Tang. In 1907, he served as President of the Bank of Guangdong. He invested in two hotels and other large and small enterprises in Chinatown, and rebuilt the cannery after the earthquake. In 1915, he served as chairman of the board of directors of the Sino-American Cruise Line. Photo taken from: [11]

The Chinese government protested against President Theodore Roosevelt after the discrimination faced by Chinese citizens during the San Francisco disaster and demanded that the United States implement the bilateral agreement to help the Chinese. Roosevelt agreed to implement strict anti-discrimination policies and relief measures for the Chinese [5, 12]. Later, a special building was built for the Chinese in Fort Winfield Scott, where most of the refugees settled. Chinese officials from Washington visited the refugee sites under the leadership of personnel from Six Companies, Inc. and expressed satisfaction with the care and assistance provided by the United States. Major General Adolphus Greeley stated in a special report on rescue operations to Washington that “there is no discrimination against the Chinese in the rescue of San Francisco and Oakland.” [6]

According to historical records, there was no distinction between the rich and the poor, business owners and laborers, and employers and employees during the earthquake relief. Everyone faced the danger together. Many Chinese servants living in Chinatown worked to help their white masters. Twenty years later, a white man named James W. Byrne recalled, “We did not have vehicles to transport mattresses and food. The Chinese walked away quietly and came back with their children’s four-wheel trucks to help us transport them. Mattresses, bedding, food and other necessities…”[6]

Arnold Genthe was a German photographer who was 26 years old when he came to the United States in 1895. He said he liked Chinatown very much and took many photos there. All the photos were damaged during the earthquake, but fortunately they were preserved and are now kept in the Library of Congress. [13]

Figure 3: the scene of Chinatown after the 1906 earthquake. On the left is the old St. Mary’s Cathedral. Picture taken

San Francisco’s Chinatown before the earthquake

In 1848, two Chinese men and a Chinese woman arrived in San Francisco on the American Eagle. They were the first Chinese immigrants to arrive in California. By December 1849, 325 Chinese immigrants moved there; by the end of 1850, there were 450 Chinese. Since then, the Chinese population in San Francisco grew rapidly from 2,176 in 1851 to 20,026 in 1852 [14]. For Chinese immigrants, the convenience of life in the Chinese community, coupled with the discrimination they faced in other parts of the city, Chinatown was the ideal location for new immigrants to stay together. The translator Ah Sing became the unofficial spokesperson for approximately 25,000 Chinese in San Francisco where he set up an office in Chinatown, between Kearny Street and Dupont Street[2]. The Chinese were concentrated on Dupont, Portsmouth Square and Sacramento Street, which gradually developed into San Francisco’s Chinatown [9]. Most of the Chinese’ houses in Chinatown were leased from the white. By the later part of 1873, 153 buildings occupied Chinatown, of which only ten were headed by Chinese. Of the 316 properties registered in 1904, only 25 were Chinese [6].

The establishment of Chinese organizations (clan associations, business associations, Chinese mutual aid associations, the tangs, etc.) were made to protect the interests of Chinese people, handle Chinese affairs, implement mutual assistance, help new immigrants solve problems, and set up courts to settle disputes. They were a government recognized by the Chinese that implemented Chinese autonomy. San Francisco’s Chinatown was mainly controlled and managed by the Six Companies and tangs. As part of the charity association, the Six Companies promoted community cooperation and protected ethnic identity in the face of discrimination and violence against first-generation Chinese immigrants in the Chinatown district of San Francisco. As a well-educated group of immigrants, wealthy merchants led the operation of the Six Companies. It played an important role in the entry and exit of Chinese immigrants in the United States. They issued documents to prove whether the immigrants had repaid all their debts and could go home. In the 19th century, they managed Chinatown successfully and efficiently. The Six Companies strived to cooperate with local governments in an attempt to quell mainstream society’s racial discrimination and persecution of Asians. [2]

Figure 4: The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in San Francisco (the Six Companies). The photo was taken in Chinatown, San Francisco by the author.

The tangs’ original intentions and goals were good to protect their countrymen from discrimination by others, as well as criminals in general. In 1854, there were three tangs in the San Francisco area: Chee Kung tong, Hip Sing tong and Kwong Duck tong. Regarding the founder of Chee Kung Tong, Hongmen believed that it was Lin Ying, and it was also said that Low Yet (1850-1864), a man of Chen Jingang of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, who fled to the United States before the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom movement was subdued.[15] According to the works of Liu Boji, an overseas Chinese historian, the order of the hall masters in the nineteenth century was as follows: Lin Ying, Ou Yingyun, Gao Jingju, Wu Guangming, and Huang Sande [16]. Chee Kung Tong was a prestigious tong.

Later, the tongs continued to increase, split, and merge, and no one knows exactly how many tongs were established. It is estimated that there were between nineteen and thirty. In 1887, the number of people attending these tongs ranged from 50 to 1,500 per tong. The tong did not have too many requirements for new members to join, and there was no restriction on how many tongs people could be members of. There was legal business as well as illegal activities operating in tongs. They competed for territory and forced Chinese merchants to pay “protection fees.” The tong also had several fluent English speakers who communicated to the outside world, even dealing with “foreign” lawyers and other Americans [15].

In the early 1850s, the crime rate in Chinatown was very low, and there were almost no major murders, rapes, armed robberies or assaults. However, lured by the profits from illegal activities, crimes in Chinatown increased dramatically in the late 1880s, especially prostitution (Bartlett Alley), drug use (Duncombe Alley), and gambling (Ross Lane, the Street of Gamblers). According to reports, before the earthquake, the door of the tong house was particularly strong, made of multi-layer wooden boards, in order to slow down the speed of police breaking the door and biding more time to hide evidence. In addition, there were tunnels connecting buildings underneath Chinatown, which were used during surprise police inspections [15]. However, the existence of these underground worlds have not been confirmed after the fire burned Chinatown to the ground. According to reports in some publications, Chinatown had a 30-foot-deep underground passage, which was actually a facility built for tourism purposes. [5]

The long-term anti-Chinese immigration policy had caused a serious imbalance in the ratio of men and women in the Chinese community. In 1850, only 8% of Chinese residents in San Francisco were women. The imbalance between men and women contributed to the demand for prostitutes. Evidently, prostitution was a lucrative commercial prospect. A large number of Chinese men could not build a family, have kids, and many died alone. Because they had no wives or children to accompany them, single Chinese men lived in terrible mental and physical conditions. Many suffered from depression that was only temporarily relieved by gambling and smoking opium. Opium was first introduced to the United States through the ocean pearl fleet in San Francisco in 1861. It is estimated that 16-40% of Chinese used opium and 10-20% of Chinese were addicted. [2, 17]

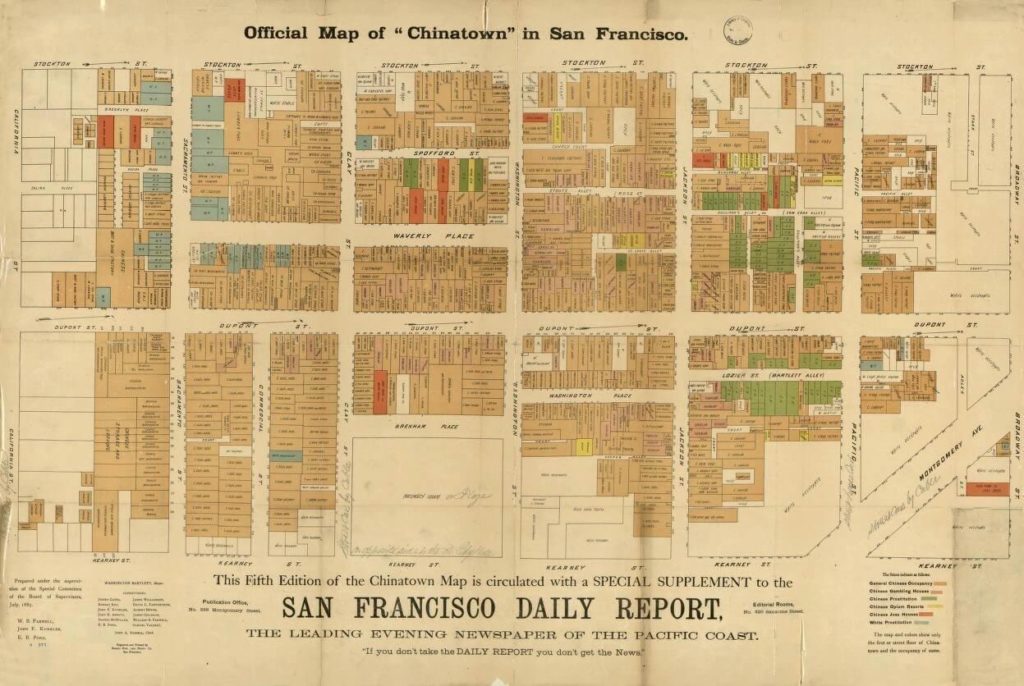

Figure 5: a map of the surviving Old Chinatown showing the layout of streets and alleys in 1885. Dupont Street is the main street in Chinatown and the first street in San Francisco. The brown parts of the map were locations occupied by the Chinese, and the red parts were the houses owned by the Chinese. The pink was a casino opened by the Chinese, the green building was a Chinese brothel, and the yellow part was the location of a Chinese opium house. The Brothel for whites is marked in blue. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Picture taken

There were full-time guards in tongs, who were responsible for security. It is estimated that they accounted for about 20% of the members of each tong. The thugs were loyal to their gang and fought fiercely. They usually used daggers or axes in close combat and Colt .45 revolvers at long distances [15]. However, the residents of San Francisco’s Chinatown were soon tired of crime and corruption. To fix this, the Six Companies tried to restrict the rise of tongs. In 1862, the Six Companies participated in the fight against illegal prostitution and sent rescued prostitutes back to their country. However, this effort was thwarted by American merchants with vested interests in the Red Light district. The Six Companies repeatedly facilitated the signing of an extradition treaty between the United States and China in an attempt to send convicted Chinese criminals back to China. [15]

In addition to organizations such as the Six Companies and tongs, the Chinese community also had religious groups, such as the earliest Chinese Christian churches and Chinese temples. The Tin Hou Temple is the oldest Chinese temple in the United States (Tin How Temple, or Tien Hou, Waverly Place). Because of the worship of the goddess Mazu, it is called the ancient temple of Tin Hou by its followers. Mazu is regarded as the protector of seafarers and was therefore worshipped by Chinese immigrants from San Francisco. The temple was built in 1852 and then rebuilt in 1911. Today, it is still a place of worship, open to the public [18].

Important dates [18]:

-The Tin Hou Temple was established in 1852.

-Construction of St. Mary’s Cathedral started in 1853.

-In 1873, the Chinese Congregational Church and the Chinese United Methodist Church were established.

-1874 Presbyterian Mission Home (later renamed Donaldina Cameron House) was established.

-In 1880, the first Chinese Baptist Church was established.

-The Salvation Army was established in 1886.

-The First China Baptist Church was completed in 1888.

-In 1894, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church was established.

-The Independent Baptist Church was established in 1905.

The Chinese had always suffered from education discrimination, and their children were not allowed to attend San Francisco’s public schools. In 1859, San Francisco established a “Chinese School” specifically for Chinese children, with the purpose of segregating education based on race. In 1885, the “Chinese School” was renamed the “Oriental School.” In addition to the Chinese, it also accepted Korean and Japanese students. In 1924, the “Oriental School” was renamed Commodore Stockton School. The first Chinese teacher hired by the school was Alice FongYu. To commemorate the late Chinese community leader, the first Chinese superintendent of the San Francisco City Department of Education, Commodore Stockton Elementary School was renamed as the Gordon J. Lau School [18].

In the 19th century, the California state government passed a series of measures aimed at Chinese residents, placing additional taxes on Chinese companies, and imposing other restrictions, such as prohibiting the Chinese from accessing public resources. In the end, Congress passed the “Chinese Exclusion Act” in 1882, suspending Chinese immigration, which was initially set to last ten years. The bill was renewed for another ten years in 1892. The Chinese population in San Francisco dropped from 25,833 to 13,954 between 1890 and 1900 [6,15]. Demographic data shows that Chinese were expelled in large numbers during this period. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1902 was again extended indefinitely. The anti-Chinese law not only prevented more Chinese from immigrating to the United States, but also sent a message to the public: the Chinese were not American citizens, and assimilation was impossible. This was an all-round suppression by the US government against the Chinese in social, political, cultural, and economic terms. [9]

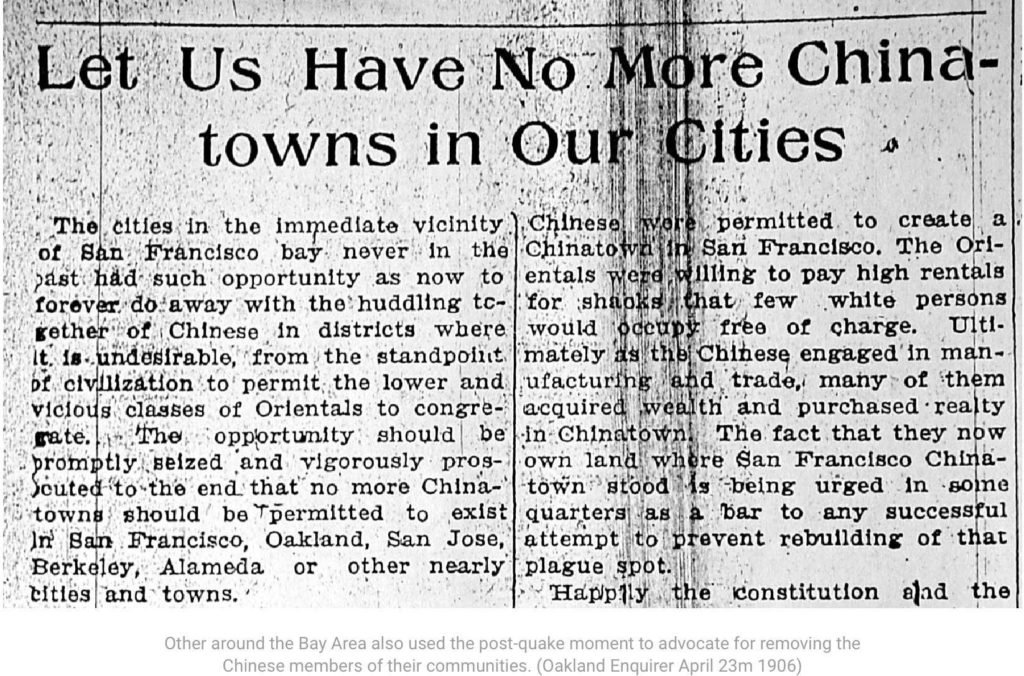

Driving the Chinese out of San Francisco

As early as the late nineteenth century, there were calls to drive the Chinese out of San Francisco. In early 1854, the San Francisco Herald published an editorial criticizing the sanitary conditions in Chinatown in hopes that the Chinese would move away [19]. In 1870, San Francisco health officials called the Chinese “moral lepers,” and spread worries that the Chinese living in the center of the city would cause the spread of infectious diseases. In the same year, the San Francisco Supervisory Board received a petition from an anti-Chinese organization claiming that “Asian cholera” spread through Chinatown, urging the board to “use some means to expel Chinese outside the city” [20, 21]. In July 1878, the radical Workingmen’s Party filed another petition to the board of directors for the order of a Chinese quarantine. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, the Chinese were lepers and Chinatown was the hotspot of leprosy [21, 22].

In 1879, California passed legislation to drive the Chinese out of San Francisco. On February 21, 1880, the San Francisco Health Board passed a resolution to formally declare Chinatown a “plagued place.” Three days later, on February 24, the board of directors issued a notice in Chinatown announcing the collective removal of residents of the area within 30 days. Faced with the terrifying situation, the Chinese panicked, afraid of large-scale raids by the health authorities. The Six Companies and other Chinese associations suggested that the Chinese should self-discipline and maintain good hygiene to avoid inciting hostility towards the Chinese. On the contrary, the Chinese Consulate in San Francisco, which was established a year before the order to remove the Chinese, adopted a more confident attitude to defend their rights. On February 26, 1880, after legal consultation, Consul Chen Lanbin warned in the newspaper that “individuals and owners of Chinatown have the right to use force to resist forced demolition.” [21]

Ten years later, on February 17, 1890, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed the Bingham Act (the Bingham Act was voted on March 3 and signed by the mayor on March 10) requiring all Chinese living in San Francisco to move to a designated area of the city within 60 days. Anyone who violated this regulation would be sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. This was the first American attempt to isolate residents on the grounds of race, which caused a shock in the Chinese community and eventually brought a lawsuit to the U.S. Circuit Court in Northern California. [21, 23]

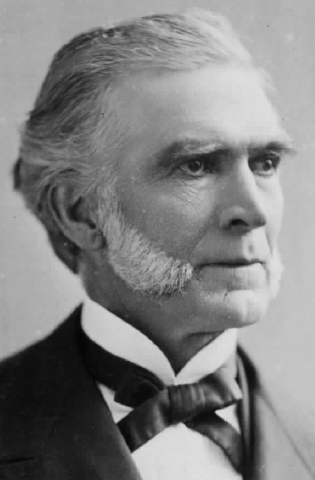

The Bingham Act went into effect on May 10, and then on May 12, the sheriff arrested a well-known Chinese merchant Lee Sing for violating the law. Chinese deputy Consul Frederick Bee went to court to deliver $2,000 to bail him out. The hearing was scheduled for July 14. On May 20, another twenty Chinese people were arrested, including the father of a sick child. They tied the Chinese together using their braids to prevent escape. The Chinese Consulate expressed indignation at the arrest. In the San Francisco consulate, a few hours after the arrest of the 20 Chinese, Frederick Bee submitted a habeas corpus application to the Federal Circuit Court in the Northern District of California, claiming that the arrest was unconstitutional [24]. On May 23, 1890, three days after the mass arrest, the Chinese Embassy in Washington wrote a letter of strong protest to Secretary of State James G. Blaine, demanding that the federal government directly intervene to stop it. But Blaine denied that the administration had an obligation to take any action. [21, 25]

Picture 6: Frederick Bee, Deputy Consul of China. Picture taken

The hearing of the Lee Sing case originally scheduled for July 14 was postponed for a few weeks, and the court debate was held on August 18. Finally, Circuit Judge Lorenzo Sawyer declared the Bingham Act unconstitutional on August 25, because the act was not aimed at preventing any vice or evil, but rather designed to forcibly expel more than 20,000 people from their homes. The Bingham Act was essentially depriving Chinese people the right to own property [21].

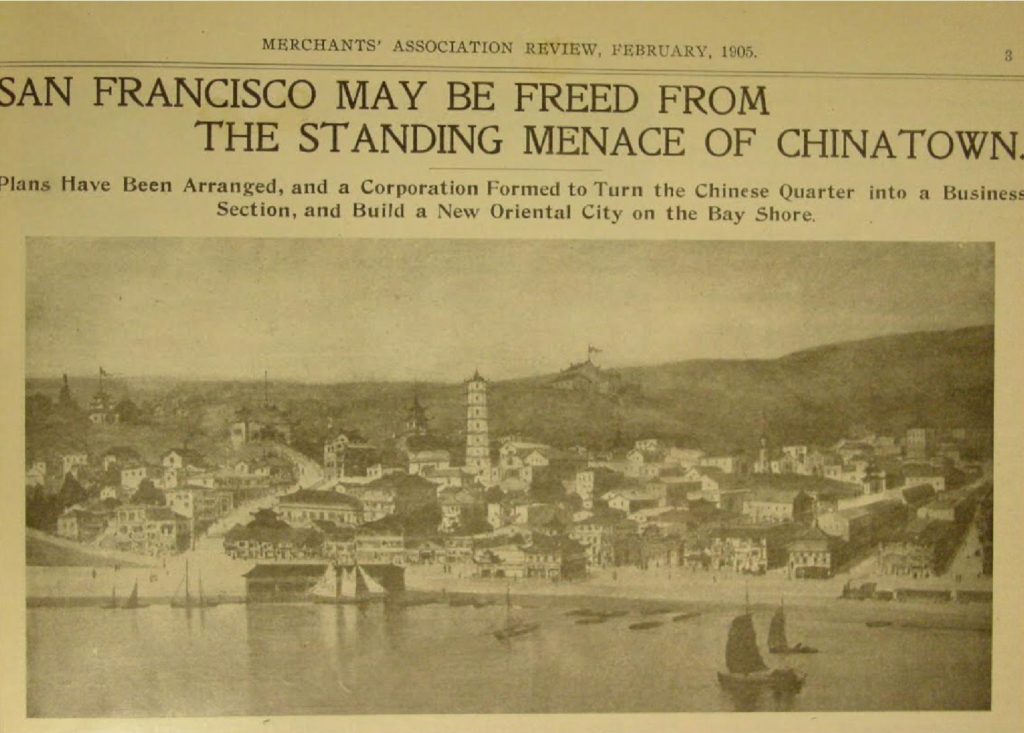

Chinatown was located in a prime location in the center of San Francisco and was a major commercial hot spot. This geographical advantage made the Chinese an enemy in the eyes of some white people, who wanted to force the Chinese to move away so they could own the real estate there. In order to achieve this goal, in 1904, a few white people registered and established a public company. Vice President and Spokesperson John Partridge vowed to acquire at least two-thirds of the real estate in Chinatown, and at the same time drive out all the Chinese to some remote area to live, which would then become places for tourism. This plan allowed the company to acquire several blocks of real estate. [26]

Picture 7: In February 1905, Menace of Chinatown article, Merchants Association Review, 1905. It announced plans have been arranged, and a corporation formed to turn the Chinese Quarter into a business section, and build a new oriental city on the bay shore. Picture taken

Relocation and reconstruction

The San Francisco residents had the most determined, optimistic spirit. After the earthquake, they displayed a strong sense of community and battled against many difficulties to rebuild their homes. The Chinese, like these San Francisco residents, were actively involved in community reconstruction. However, white people began to fight them to gain more profits, and were seriously lacking in aiding disadvantaged groups and caring about public interests. [4, 5, 26] In 1906, sixteen years after the overthrow of the Bingham Act, San Francisco was presented with the opportunity of post-earthquake reconstruction. However, the state government, city officials, and local residents began pointing fingers of blame, claiming that the Chinese occupied the precious resources in the center of the financial district. The white people scornfully called Chinatown the “Oriental Hell” and demanded that Chinatown be moved from the city center to Hunters Point in the southern suburbs. [5, 9]

A local newspaper by the name of The Overland Monthly boldly stated that, “fire has reclaimed to civilization and cleanliness the Chinese ghetto, and no Chinatown will be permitted in the borders of the city. ” Other media (such as the Independent, Britannia Blackwood’s Magazine) hailed the removal of Chinatown, “polluting the sewers, the evils of the past, crumbling houses, opium houses, gambling dens, brothels, and tongs in every corner of the city.” The white-dominated media unanimously called for the “cleansing” of San Francisco by removing Chinatown. [9, 27] The San Francisco examiner’s report mentioned: According to the people who manage the property in Chinatown, the land in Chinatown would be sold to wealthy white people to build high-end residences. Chinatown is located next to the business district, with a beautiful port and river, behind which holds a small hillside sheltered from the wind. Although Chinatown has been burned down, the real estate value is still high. Many people have begun to bargain for the land.

Picture 8: Only five days after the earthquake, a reporter from the Bay Area City News took the opportunity to suggest driving the Chinese away from their homes in Chinatown. Photo taken

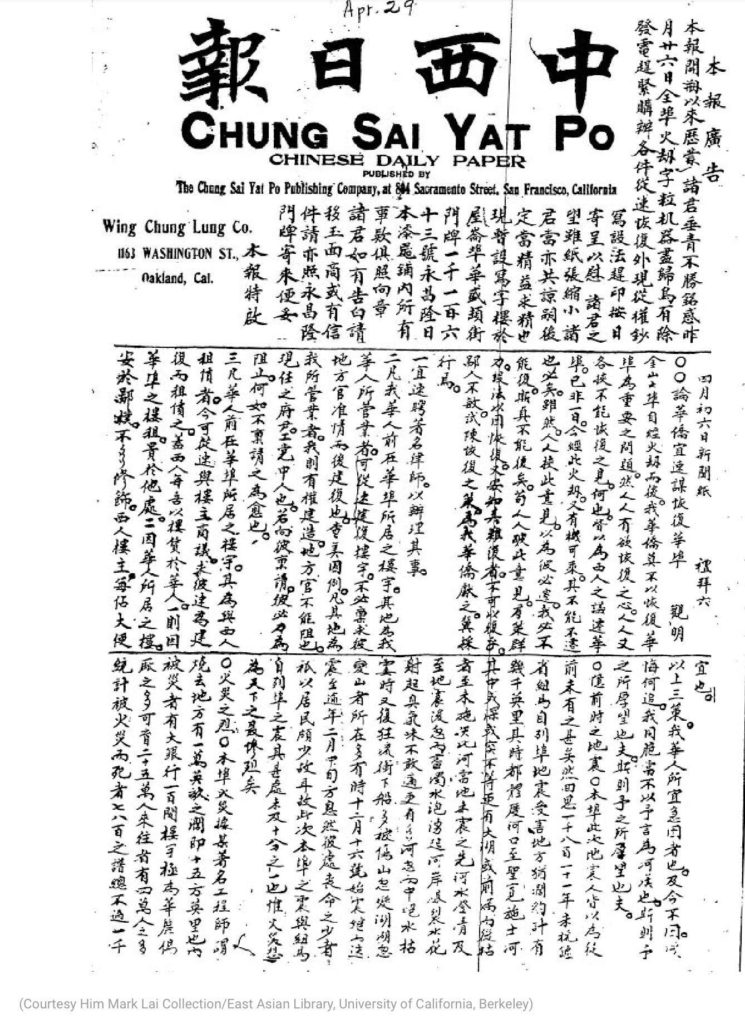

Chung Sai Yat Po, the first Chinese newspaper in Chinatown which resumed operations after the earthquake, helped the Chinese community to come up with solutions to the problem they faced. Editor Ng Poon Chew (March 14, 1866 – March 13, 1931) presented three suggestions for saving Chinatown: 1. Hire well-known lawyers as soon as possible to protect the interests of the Chinese. 2. The Chinese in Chinatown who own real estate should rebuild their buildings as soon as possible. According to US law, land belongs to the owner of the building, and the landlord has the right to rebuild on his land without notifying local officials. 3. The Chinese who have rented houses from white people should talk to their landlords as soon as possible, requesting that their housing be rebuilt and rented.

Picture 9:Chung Sai Yat Po called on the Chinese to unite and insist on rebuilding Chinatown in situ. Photo taken

In the face of possible relocation, the Chinese organized public demonstrations and protests through print media. They put economic pressure on the San Francisco government by boycotting American products and discussing moving to other cities to do business. [9, 28] For example, The Oakland Tribune reported on May 10, 1906 a protest by a Chinese organization against relocation, and published a protest speech by the pastor of the Berkeley First Chinese Congregation. The Chinese translator of the Alameda County Court, Gee Gam, asserted that “the Chinese will never accept this kind of exploitation.”[9]

The calls to remove the Chinese from their homes was undoubtedly an extreme act of racism. Chinatown community leaders, the Six Companies, several Chinese-American organizations, local Catholic and Protestant churches, the California education system, local politics, business elites and companies, Chinese diplomats, first and second generation Chinese immigrants, and both men and women mobilized to oppose the plan to remove the Chinese. The Chinese struggled and fought, exerting economic pressure and international political pressure from their home country, and finally pushed for the reconstruction of San Francisco’s Chinatown. [9]

The Six Companies began to communicate with the Chinese government to pressure the California government to rebuild Chinatown in the same location. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Chinese consulate officials met with Governor Pardee on April 30, 1906, and made a statement of opposition to forced eviction: “The United States is a free country, and everyone has the right to own property.” In early 1907, the Chinese government claimed that the Chinese had the right to rebuild Chinatown. Chinese officials threatened to suspend trade if the Chinese community was not allowed to rebuild.[5]

The first generation of Chinese immigrants had been defending their rights in the United States for decades and knew how to face injustice. They certainly did not stay silent about the protest for eviction. Instead, they used “true American values” to question why Chinese people should be singled out. They protested that the mayor had no right to discriminate against the Chinese, and that the Chinese had the right to live on the land they owned! Many Chinese representatives met with local officials and issued an open letter to the governor reiterating these rights. [9]

The second generation of Chinese Americans issued a strong debate against the relocation of Chinatown. These second-generation Chinese accepted “American” values and also held the same traditional values as their first-generation family members. As American citizens and land owners, they boycotted the government’s policies and legislation, demanded equal rights under the law, and opposed racial prejudice. Because allowing the Chinese to stay in Chinatown was beneficial for long-term leases, Chinese renters who did not own real estate also received the support of white landlords. [9] The irony is that San Francisco had a restrictive housing contract that prohibited the Chinese from settling in other places, so plans to relocate to Chinatown would have faced many more obstacles. [29]

It is worth mentioning that in considering the various factors of the reconstruction of San Francisco’s Chinatown, economy was an important factor, and because of this, American society had tolerated Chinese culture. At first, the Chinese were seen as a financial burden on the United States. However, the annual turnover of the Chinese in the US was 30,000,000 dollars. Chinatown and its Chinese residents benefited many merchants and promoted economic development. Indeed, some people in San Francisco worried that the discriminatory treatment of the Chinese there may negatively impact trade with Asia. Chinese merchants also warned that “China is one of the largest American commodities and markets in the world. Discriminating against the Chinese will cause huge losses to San Francisco’s economic interests.”

California State Senator James D. Phelan, a member of the San Francisco General Relief Committee, a committee to oversee the permanent relocation of the Chinese quarter,suggested that the Chinese should be moved to Hunter Point, but another committee member Gavin McNab disagreed. He pointed out that Hunter Point was just across from San Mateo County. San Francisco needed Chinese property taxes more than ever. The committee negotiated with the Chinese community and finally reached an agreement on July 8: Chinatown would be rebuilt in its original location from before the earthquake. [9]

The work of rebuilding homes after the earthquake was finally happening. In fact, before discussing the plan to relocate Chinatown, the Chinese had already begun to rebuild. The reconstruction plan needed sufficient financial support. After the earthquake, insurance companies paid about 80% of claims. Only Chinatown was caught in economic trouble without compensation. At that time, Chinese merchants could not obtain reconstruction loans because they did not have stocks or collateral. Until the beginning of 1907, they had to rely on the internal credit system and other activities to support the Chinese community. [5] Several Chinese entrepreneurs, along with the Six Companies, contributed to the reconstruction of Chinatown. In order to reduce the discriminatory rhetoric against the Chinese, the companies emphasized that the Chinese in San Francisco should become more “Americanized” to help fund reconstruction [9, 30].

In order to avoid the negative stereotypes of overcrowding and sordidness, Chinese merchants, including Look Tin Eli (1870-1919), and Tong Bong planned a new “Oriental” city, with a uniform layout of streets, hutongs, and apartments. The hotels were dense but bright, clean, and orderly, and the destroyed wooden buildings were replaced with masonry buildings. After reconstruction, the quality of the buildings were better than before, with an “Oriental” style, full of colors and decorations of the Chinese culture [5], which made Chinatown more attractive to tourists. A few months after being condemned as an economic and cultural burden, the public began to accept and even appreciate these Chinese cultural elements. [6, 9]

Picture 10: Look Tin Eli (left) and his brother Lee Eli (right). Look Tin Eli was a San Francisco merchant who founded the Guangzhou Bank. He returned to China from 1879 to 1884 to study language and culture. When he returned to San Francisco, he was barred from entering the United States. Look Tin Eli appealed to the Federal Court and eventually won his case. His brother Lee Eli was also a wealthy banker. Picture taken

The earthquake and fire destroyed the entirety of Chinatown– Old St. Mary’s Cathedral was the only surviving building. Old St. Mary’s Cathedral, built in 1853, was the first Asian church in North America. The two-story building was once the tallest building in San Francisco and one of the earliest non-brothel buildings in San Francisco. The restoration of the church started quickly, and the reconstruction was completed in 1909. After the restoration, the main style of the church was Victorian Gothic in style with added touches of Chinese cultural elements [18].

Picture 11: St. Mary’s Cathedral reconstructed after the disaster. Opposite to St. Mary’s Square, a 12-foot statue of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China, stands here. Picture taken

The reconstructed Chinatown was full of traditional Chinese culture, and many buildings were decorated with pagodas. Sing Fat leased an estate worth up to $135,000 at the junction of Grant Street (Dupont Street) and California Street. Charles M. Rousseau’s new Chinese-style Chee Kung Tong building was valued at US$25,000 and was located at 36 Spofford Alley. [6]

Picture 12: Sing Fat Building. Sing Fat Company is an import and export company (left) and Sing Chong Building (right) were the first constructed buildings in Chinatown after the earthquake, built in 1907. Photo taken

Since its establishment in the 1850s, San Francisco’s Chinatown had constantly been discriminated against, facing the danger of relocation many times. After the earthquake and fire in 1906, San Francisco’s Chinatown rebuilt itself from the ruins of disaster. As of 1910, the number of native-born Chinese in the United States reached 14,935, which was one thousand more people than in 1900. The second generation of Chinese immigrants invigorated a new force into Chinese society and its population became more diverse. [6] The ancestors of the Chinese utilized wisdom and perseverance to fight to preserve the oldest Chinatown outside Asia and the largest Chinese community in the United States.

References:

1,Peter Booth Wiley, National trust guide- San Francisco: America’s guide for architecture and history travelers. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2000): pp 4–5.

2,Richard Dillon, The Hatchet Men: The Story of the Tong Wars in San Francisco’s Chinatown. (New York: Coward-McCann, 1962): pp 3-67.

3, J. Eugene Haas, Robert W. Kates, Martyn J. Bowden, eds., Reconstruction Following Disaster. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977): pp 4.

4,Philip L. Fradkin, The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906. (University of California Press, 2006): pp 216-244.

5,Christoph Strupp, Dealing with Disaster: The San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. (UC Berkeley) https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gd2v192

6,Dillon, 1962: pp 252-266

7,Raymond Sullivan, Retracing the events of the 1906 earthquake and fire along the old bay margins in downtown san francisco. 2006 http://www.ncgeolsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2006-1_Retracing-Events-of-1906-Earthquake_MASTER.pdf

8, Gladys Hansen, “Who perished”: http://www.sfmuseum.org/perished/index.html.

9,Sarah Littman. Race, Immigration, and a Change of Heart: A History of the San Francisco Chinatown 2016.

https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1395&context=etd

10,Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, “New Chinatown Near Fort Point: Oriental Quarter Removed from Presidio Golf Links at Request of Property Owners” San Francisco Chronicle, April 28, 1906. Last modified July 16, 2004. Accessed March 7, 2016. http://www.sfmuseum.org/chin/4.28.html

11,Connie Young Yu. Lew Hing: A Kinsman to the Rescue. https://www.chsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Lee-Yoke-Suey.pdf

12,Howard K. Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987): pp 172-252.

13,Chris Preovolos. Before the fires: Arnold Genthe’s Chinatown, 2015. https://www.sfgate.com/art/article/Arnold-Genthe-s-Chinatown-6192523.php

14,Beth Lew-Williams. The Chinese Must Go. Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America. (Harvard University Press, 2018): pp 21.

15,Dillon, 1962: pp115-154.

16 http://news.sina.com/singtao/104-103-102-106/2006-08-19/09121226875.html

17,Dr. Weirde. Chinatown’s opium dens. http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Chinatown%27s_Opium_Dens

18, Michelle Chow. Tiger Business Development Inc. http://www.sanfranciscochinatown.com/history/index.html

19,San Francisco Herald, August 22, 1854.

20, Health Officer’s Report, Board of Supervisors, San Francisco Municipal Reports for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1870, Ibid. at 233.

21,Charles J. McClain, In Re Lee Sing: The First Residential-Segregation Case, 3 Western Leg. Hist. 1990: pp 179-196.

22, San Francisco Chronicle, July 26, 1878.

23, Ibid. In 1882 the then city and county attorney had informed the board that such action would in his view be unconstitutional. Daily Evening Post, May 2, 1882.

24,Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, Case File, In re Lee Sing et al., Case 10730, Record Group 21, Old Circuit Court Cases, National Archives, San Francisco Branch.

25, Pung to Blaine, May 23, 1890, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, H.R. Exec. Doc. I, pt. I, Slst Cong., 2d sess. (Washington, 1891) 219-20.

26,Anna Naruta, Chung Sai Yat Po; Danny Loong. (2006). Relocation. Earthquake: The Chinatown Story. Chinese Historical Society of America Museum exhibit

27,Alexander Saxton, The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and the Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975): pp 2.

28,Him Lai, Genny Lim, and Judy Yung, Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island 1910- 1940 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991): pp 1.

29,Victor Low, The Unimpressible Race: A Century of Educational Struggle by the Chinese in San Francisco. (San Francisco: East/West Publishing Company, Inc. 1982):pp 92.

30, Fredrick Wakeman, Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997): pp 62.

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing

this post plus the rest of the site is really good.