Author: William Tang

Translator: Joyce Zhao

ABSTRACT

Huie Kin, the first ordained Chinese pastor in Chinatown, New York, married Louise Van Arnam, the daughter of a Dutch-American manufacturer from Troy, New York, in 1887. They had three sons and six daughters. The three Huie sons married American women and worked in the U.S. in engineering or publishing. All six daughters married Chinese students and went to China in educational, religious or medical work.

The oldest, Harriet Louise (B. A. Hunter College) married Zhang Fuliang, a graduate of Yale School of Forest, who taught at Yale-in-China and directed rural rehabilitation programs. During the latter part of World War II Harriet was employed by the Christian Mission Board.

The second, Alice graduated from Teachers College, Columbia University and joined the Y. W. C. A. in Shanghai, where she taught Physical Education and Hygiene. In 1921 she married Yan Yangchu (James Y. C. Yen,M. A. Princeton), founder of the Mass Education Movement.

The third, Caroline who graduated from Teachers College, married Zu Yuyue (Y.Y. Tsu, Ph.D. Columbia), who became an Episcopal Bishop of southern China. She became Dean of Women at St. John’s University in Shanghai in 1935 and served as a chairman of the National Board of the Y.W.C.A. in 1938-39.

The fourth, Helen finished at Cornell Medical College and married Gui Zhiting (Paul Kwei, Ph.D. Princeton), who taught physics at Central China University in Wuhan. She taught English at Wuhan University until she retired.

The fifth, Ruth attended Wooster and married Zhou Xuezhang (Henry Chou, Ph.D. Columbia), who became Dean of the College and Professor of Education at Yanjing University. Ruth taught physical education at Yanjing and later served as the Official Hostess of the University.

The youngest, Dorothy (M.A. Columbia) married Wang Yihui, M. D. (Amos Wong, Johns Hopkins) and both taught at the Beijing Union Medical College. She later taught microbiology at St. John’s University in Shanghai from 1942-44.

~~~~

The founder of the First Chinese Presbyterian Church of New York City, the first Chinese pastor Huie Kin (1854-1934), was Sun Yat-sen’s bosom friend. Huie Kin strongly supported Sun’s leadership in the Chinese Democratic Revolution, and each time Sun came to New York, he would live in Pastor Huie’s church dormitory.

Figure 1. New York City’s first Chinese Christian elder. First Chinese Presbyterian Church, 61 Henry Street. Image source

In 1854, Huie Kin was born in Taishan, Guangdong, China, and in 1868, he came to America when he was 14. He then became a Christian, and he studied at a seminary to become a pastor. In 1887, Huie Kin was married to Louise Van Arnam (1864-1944), and they had three sons and six daughters.

Figure 2. Huie family portrait in around 1911. Front (left to right): Louise, Ruth, Huie Kin, Arthur, Louise Huie, Albert, Dorothy, Alice. Back (left to right): Caroline, Irving, Helen. Image source

When their three sons grew into adults, they all married wives of American descent. Their six daughters, who all received higher education, were all married to Christian Chinese international students.

After the six daughters got married, all of them accompanied their husbands back to China. The six couples had happy, fulfilling lives after marriage, giving birth to many children, living through the sweet and the bitter together, their relationships strong with love. Most lived to be old-aged, some living beyond 100 years old.

The six sons-in-law of Huie Kin were all extremely outstanding international students of their generation who contributed immensely to modern Chinese society. Thus, the family that Huie Kin’s children formed has a nickname of “Republic of China’s best academic family”.

Figure 3. Fu-liang Chang.

His eldest daughter, Harriet Louise Hai-li Huie (1893-1991), graduated from Hunter College, and she married Fu-liang Chang (1889-1984), who graduated from the Yale School of the Environment.

A student from Jiangsu, China, Fu-liang Chang was the first batch of Boxer Indemnity Scholars in 1909. He studied environmental studies at Yale. After he returned to China, he first taught at Yali Middle and High school in Changsha. In 1930, he threw himself into the rural construction movement, and in 1940, he participated in the industrial cooperative movement. As an agricultural expert, he worked hard at the grassroots level of the country, living up to a scholar’s core values of serving his country.

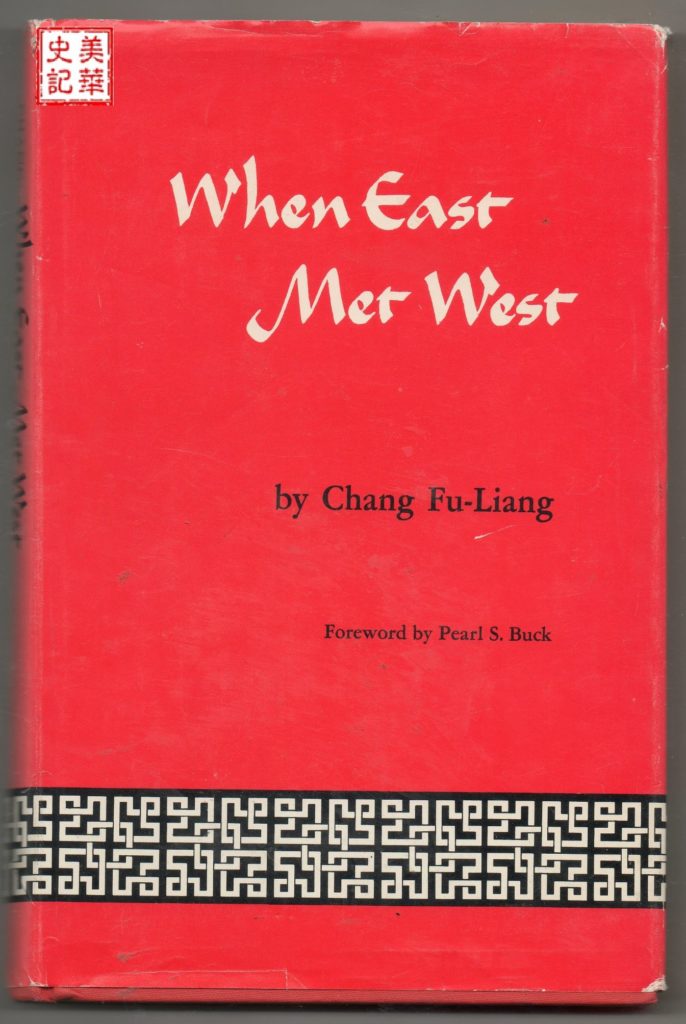

Fu-liang Chang’s book When East Met West: A Personal Story of Rural Reconstruction in China, foreword written by Pearl S. Buck, was a document of the Christian experimental movement in rural Jiangxi. It was published in 1972 by Yale-In-China Association.

Figure 4. Fu-liang Chang’s book When East Met West: A Personal Story of Rural Reconstruction in China.

Figure 5. James Y. C. Yen.

Huie Kin’s second eldest daughter, Alice Ordania Ya-li Huie (1895-1980), graduated from Columbia University’s Teachers College, and she married James Y. C. Yen (1890-1990).

James Y. C. Yen was born in a rural village of China’s Sichuan province, and under the encouragement and nurturing of Christian missionaries, he went to school in Hong Kong. Later, he studied abroad in America, earning a bachelor’s degree from Yale University and a master’s degree from Princeton University. During World War I, James Y. C. Yen went to France battlegrounds to help support the chemical work, where he realized the importance of literacy education for the common people.

In 1920, after James Y. C. Yen went back to China, he threw himself into the education of the common people and rural construction, carrying a wave of intellectuals to the countryside.

After returning to China, he first coordinated civilian education work in the intellectual department of the Shanghai Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) National Association, writing and publishing textbooks such as Civilians’ Thousand Characters Lesson. In 1922, James Y. C. Yen initiated a national literacy movement using the slogan “Eliminate illiteracy, become a new citizen”. In March of that year, he went to Changsha, Hunan to organize a civilian education conference, where he promoted his “City-wide Civilian Education Campaign Plan”. Not long after, his fundraising team built 200 civilian schools, the students adding up to over 2,500 in total. This national literacy movement’s experiment in Changsha was James’ first big scale experiment in civilian education, and it became hugely impactive. In fact, young Mao Zedong once volunteered as a teacher in James’ civilian education movement in Changsha.

In 1923, James Y. C. Yen went to Beijing, and under the support of many well-known names such as Zhang Boquan, Jiang Menglin, Tao Xingzhi, the then prime minister of the Beiyang government Xiong Xiling and his wife Zhu Qihui, on March 26, the Chinese Civilian Education Advancement Association was established, with James as the general director. After the organization was established, it successively opened volunteering literacy events in northern China, central China, eastern China, western China, southern China, etc.

James Y. C. Yen gradually realized that the importance of civilian education was on the education of the farmers, and his organization chose Dingxian county, Hebei province as the pilot of civilian education. He thought that the heart of the problem in Chinese farmers was “ignorance, poverty, cowardness, and selfishness”, and he suggested using the three aspects “school mode, society mode, and family mode” to solve the problem. “Use literature and art education to solve ignorance, use career education to solve poverty, use hygiene education to solve cowardness, and use civic education to solve selfishness.”

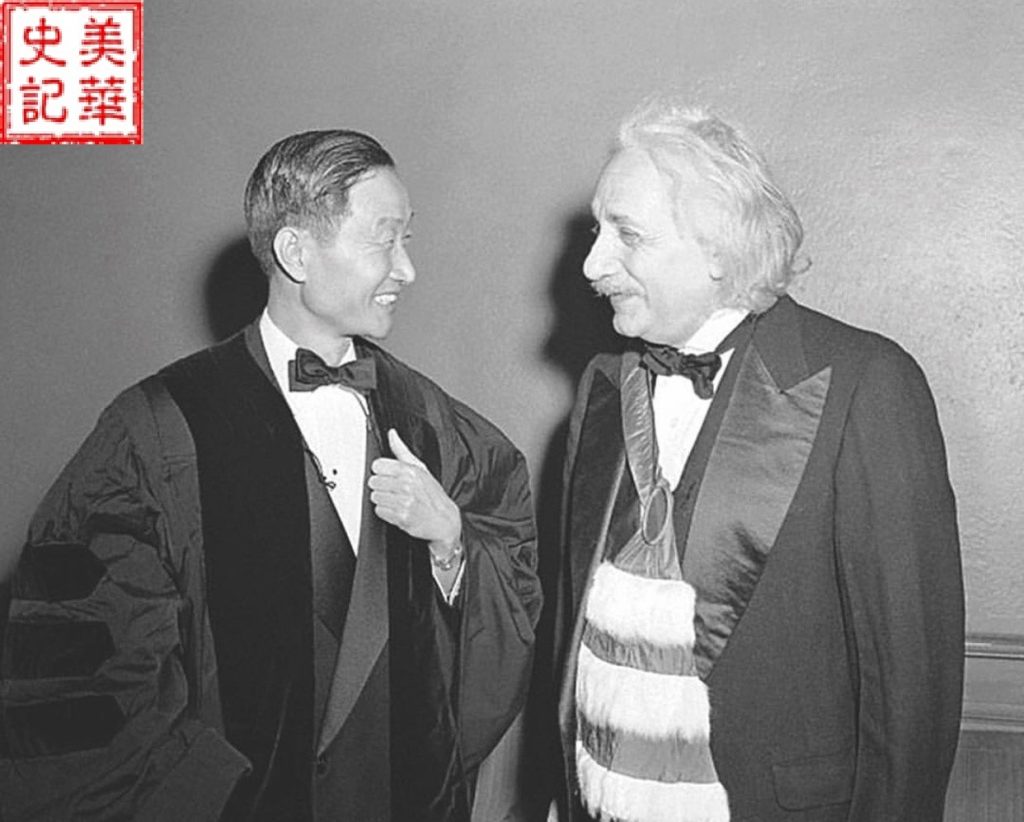

His work gained the attention of Nobel Prize for Literature’s winner Pearl, who published an interview with him titled “Tell the People”. James Y. C. Yen’s ideology received international recognition. In 1943, the 400th anniversary of the death of astronomer Copernicus, many higher academic institutions in America selected ten outstanding individuals of the generation with revolutionary contributions. James Y. C. Yen was the only Asian in the list, which included many well-known individuals such as Albert Einstein, Henry Ford, Walt Disney, and John Dewey, to step on the same stage and receive the award.

Figure 6. 1943, James Y. C. Yen and Albert Einstein before wave theory Navy work Iola Register KS June 1. Image source

October 20, 1949, James Y. C. Yen flew from Chongqing to Taipei to participate in a China rural rehabilitation joint committee meeting. The construction of rural Taiwan utilized much of James Y. C. Yen’s knowledge and experience working in rural Hebei, laying an important foundation for Taiwan’s economic take-off in the future. A week later, he went to Hong Kong, then America. In America, he supported South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia’s developing countries in advancing the civilian education movement.

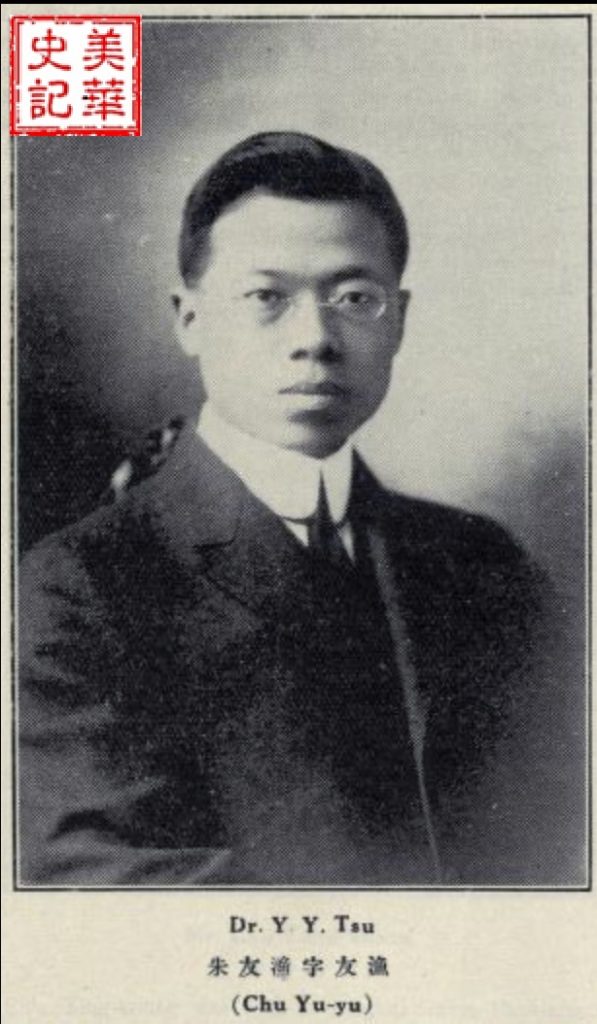

Figure 7. Andrew Yu-yue Tsu.

Huie Kin’s third eldest daughter, Carolina Alida Ling-yu Huie (1897-1970), graduated from Columbia University’s Teachers College, later becoming the first director of the women’s college at Shanghai St. John’s University. She married Andrew Yu-yue Tsu (1886-1986), who graduated with a PhD from Columbia University.

Andrew Yu-yue Tsu was from Shanghai, and he was one of the first four graduates of St. John’s University in 1907. After serving at a church in Wuxi, Jiangsu for two years, he went to America in 1909, enrolling in the General Theological Seminary in New York. After, he enrolled in Columbia University, receiving a master’s degree and a PhD degree in theology.

In 1912, Andrew Yu-yue Tsu went back to China, and he became a sociology professor at St. John’s University. In 1924, he became the pastor of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. In 1925, Sun Yat-sen fell ill and passed away in said hospital, and due to the requests of family members, a memorial service was held there. Liu Tingfang and Andrew Yu-yue Tsu co-directed the service. During World War II, Andrew Yu-yue Tsu served at the Yunnan-Burma Highway, thus gaining the nickname “Yunnan-Burma Highway Bishop”. In August of 1947, the Chinese Anglican General Assembly decided to establish a headquarters in 152 Minhang Road, Hongkou, Shanghai, with Andrew Yu-yue Tsu as the general director. In July of 1950, Andrew Yu-yue Tsu went to Toronto, Canada to participate in the central committee meeting of the World Council of Churches. After returning to China, he left Shanghai once again on December 7, 1950, heading for Hong Kong, then redirecting to Los Angeles, USA. In April of 1951, during the Chinese Christian persecution movement, Andrew Yu-yue Tsu was the first to be attacked among the four Chinese Christian leaders. In 1986, Andrew Yu-yue Tsu passed away at age 100.

Figure 8. The report of Andrew Yu-yue Tsu’s death. Image source from: The News-Journal Papers. Monday, April 14, 1986.

Figure 9. Paul Kwei.

Huie Kin’s fourth daughter, Helen Pierson Hai-lan Huie (1899-1995), graduated from Weill Cornell Medicine, and she married Paul Kwei (1895-1961), who held a PhD degree from Princeton University. She taught at Wuhan University, eventually becoming the director of the school of foreign languages.

Paul Kwei was from Shashi city, Jiangling county, Hubei province, and he was born into an Anglican pastoral family. His father was both the president of the Shashi city Anglican church and the principal of the elementary school. Paul Kwei was baptised at a young age, where he was named Paul.

In 1912, Paul Kwei entered Tsinghua University’s higher level liberal arts with outstanding marks. In 1914, he was guaranteed admission to Yale University, where he first went into the liberal arts, then changed paths to study STEM. In 1917, he received his bachelor’s degree, then entered the University of Chicago graduate school.

At the time, World War I was raging, and an international youth organization was recruiting Chinese people to France to support Chinese workers for trench warfare. Paul Kwei answered this call, and after arriving in May of 1918, he taught the Chinese workers how to read, write letters to home, and also took on other tasks to improve life welfare. After the war ended, in June of 1919, he returned to America to continue his education. This time, he enrolled in Cornell University, researching radio. He received his master’s degree in 1920, and he returned to China in the same year. In 1923, when Paul Kwei was teaching at Changsha Yali University, he received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation to continue his education at Princeton University. There, he conducted research on gas discharge and UV spectroscopy with famous physicist K.T. Compton, receiving his PhD in 1925. He returned to China afterwards, committing himself to research and teaching at many institutions of higher learning. For many years, he directed Huazhong University, Wuhan University’s physics department, and Wuhan University’s school of science, cultivating scholars of science for the country.

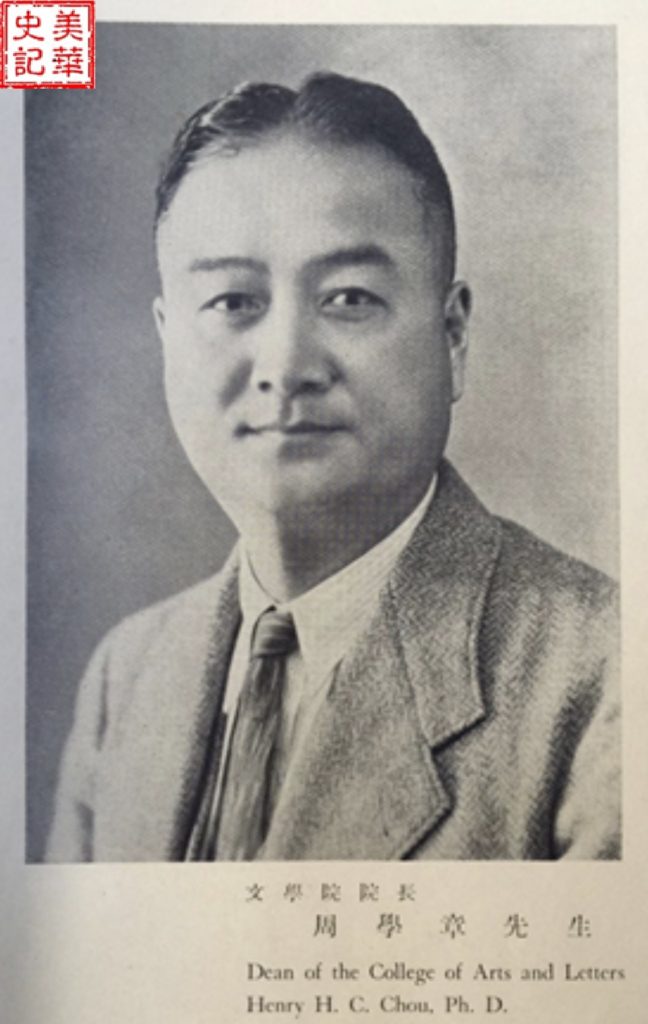

Figure 10. Henry Hsieh-chang Chou.

Huie Kin’s fifth daughter, Ruth Gorham Shu-wen Huie (1901-1990), graduated from Wooster College’s physical education department. Afterwards, she taught basketball, badminton, etc. at Yanjing University, and she married Henry Hsieh-chang Chou (1893-1945), who held a PhD degree from Columbia University.

Henry Hsieh-chang Chou was born in a suburb in today’s Tianjin, Xincheng county. Ever since he was young, he studied diligently, and his self studying abilities were strong. He studied at Tianjin Provincial Teachers College and Baoding Teachers College, and because of his academic excellence, he was awarded funding from the provincial government to study abroad in America. Later in 1919, he graduated from Oberlin College with a bachelor’s degree, enrolling in Columbia University after and receiving his PhD degree in 1923.

After completing his education, he returned to China and became the liberal arts school director and physical education department director of Yanjing University. In Henry Hsieh-chang Chou’s work in education administration, not only did he expand and advance the physical education department’s teaching curriculum and academic research, he also actively promoted rural education. He specially went to Europe to observe the educational situation in various countries, and he collected foreign textbooks. Henry Hsieh-chang Chou took initiative and actively promoted four main aspects of academic education, societal education, hygiene education, and career education to realize the goal of “eliminating poverty, creating wealth” in bettering the country through education. In 1937, he successively created the Chengfu Teachers College and the Rancun experimental district, making significant contributions to Chinese rural education.

During World War II, Henry Hsieh-chang Chou and many teachers at Yanjing University were imprisoned by the Japanese military, undergoing intense torment, but never bending to the Japanese power. Even after leaving prison, he refused to become a Japanese puppet despite threats and lures. He was steadfast in refusing to work for the Japanese government. Unfortunately, he passed away before the surrender of the Japanese. After the war, he was awarded a commendation from the Chinese government. His wife, Ruth Gorham Shu-wen Huie, continued to expand physical education at Yanjing University and Beijing University until retirement.

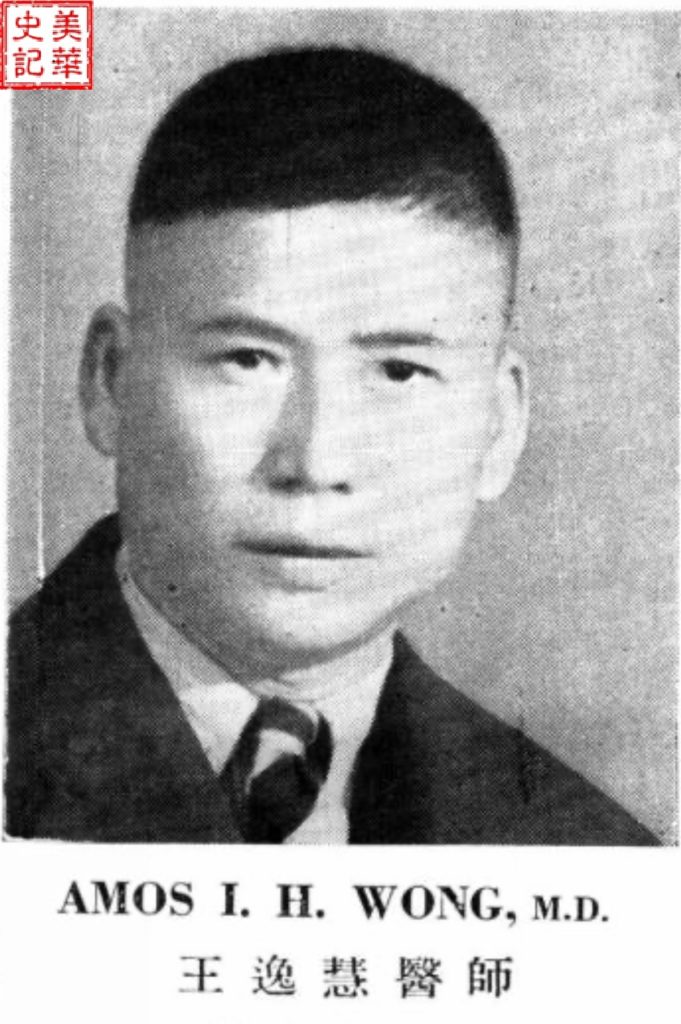

Figure 11. Amos Wong.

Huie Kin’s youngest daughter, Dorothy Esther Te-lan Huie (1902 – ?), held a master’s degree from Columbia University, and she married Amos Wong (1899 – 1958), who graduated from Johns Hopkins University.

Amos Wang was from Fuzhou, Fujian, and he was born into a poor family. From middle school to college, he worked diligently alongside studying. In 1923, he graduated from the medical school of St. John’s University with a medical PhD degree. In 1925, Sun Yat-sen was receiving his last medical treatment in the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, and the then surgeon Amos Wang was a part of the medical treatment team. In 1926, he was chosen to advance his surgical skills at the University of Cincinnati’s hospital. At the end of the same year, he transferred to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine to study obstetrics and gynecology for a year, also serving as a resident for four months at the New York State Hospital, building a solid foundation in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. Before and after studying abroad, his service at the Peking Union Medical College made significant contributions to the academic research and clinical treatment of obstetrics and gynecology.

In 1928, Amos Wang went back to China, once again returning to the Peking Union Medical College to become a teacher and resident doctor. Not long after, he was promoted to assistant professor, and he became the assistant director of obstetrics and gynecology. In 1935 he left Beijing to become the director and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at a Shanghai medical school. In 1937, he once again returned to his alma mater, St. John’s University Medical School, as a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, giving significant contributions to the construction and student cultivation of obstetrics and gynecology.

After World War II bursted into action, Amos Wang supported the anti-Japanese movement. In 1939, he collected funds to build a Shanghai wounded soldiers hospital and a Shanghai refugees hospital in the French Concession. In 1950, Amos Wang participated in the Chinese Medical Association, and he was selected as a member of the economics committee. In 1951, as a response to “support Northwestern construction”, he donated his private Shanghai union hospital to the country, and he brought a group of crucial and expensive medical treatment equipment to Xi’an. He was assigned to work in the obstetrics and gynecology department of the Second Northwest Army Hospital, and not long after, he was promoted as the hospital’s assistant director and department director. He also built a cervical cancer ward, and using the laser instruments he brought from Shanghai, he gave laser treatment to patients. In March of 1958, Amos Wang suddenly passed away due to a myocardial infarction during a teaching event.

Huie Kin’s Descendants Create a Big International Family

Pastor Huie Kin, his sons, and his daughters’ descendants branched volumously and numerously to the point where today, 400-500 of his family extends across the world. They have different skin colors of various ethnic groups, but they never forget their roots. Every few years, there will be a huge, happy family reunion. Huie Kin’s autobiography states, “Like many relatives before me, I came to the United States for gold, only to get immortal treasures and happiness that thieves could not steal”.

Figure 12. Huie Kin’s Descendants. Image source

References:

1, Huie Kin, bdcconline.net

2, 一个中西合璧大家族的源头 《文学城》

3, 东成西就的许芹家族 《海外宣教》