Author: Xi Luo

Translator: Ella Wu

ABSTRACT

Paper son: one man’s story is a memoir by Tung Pok Chin. In this book the author casts light on the largely hidden experience of those Chinese who immigrated to America with false documents during the Exclusion Act era. Also, the author’s personal story under the shadow of McCarthyism may resonate with those who have been caught in the middle.

From the beginning of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and all throughout McCarthy’s reign of terror (1954), Chinese immigrants were subject to fabricating their identities to seek refuge and opportunity in the unwelcoming arms of United States. Among these huddled masses of persecuted migrants was Tung Pok Chin.

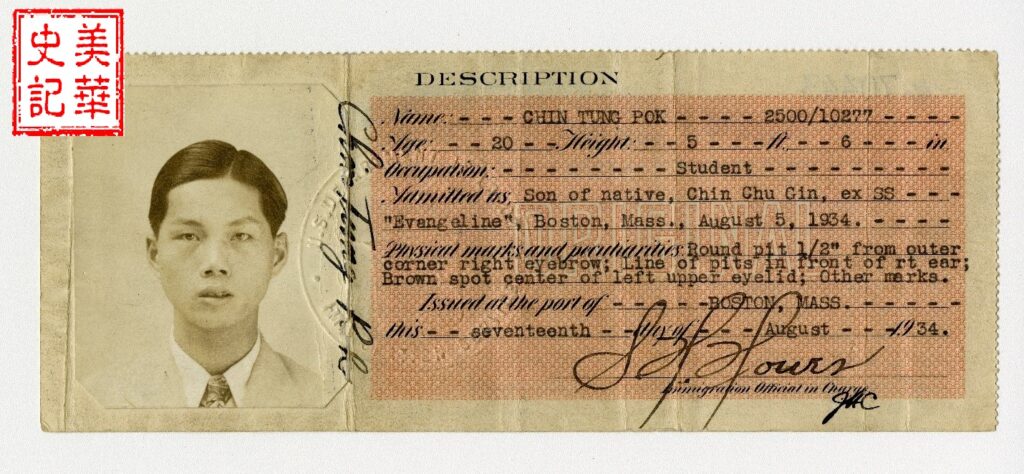

In his memoir Paper Son: One Man’s Story, Chin gives a voice to his real identity and life experience living through the Chinese Exclusion and McCarthy era. Lai Bing Chan, was born in Sha Tou Village in Tai Shan, China shortly after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. However, from the start, Chin’s identity was somewhat of a mystery. His real name and date of birth were lost when he was kidnapped by warlords and sold to a childless couple. He was raised by the Chan family as a child. In 1943, around the age of nineteen, Chin purchased a new identity in the form of a forged immigration document stating that his name was Tung Pok Chin and the son of a Chinese-American. Just like that, Chin became a paper son with a ticket into America. To pay off the debts that it cost to immigrate, Chin toiled away in the laundry industry in cities from Boston to New York. During rare breaks and restless nights, Chin taught himself English. It was his lifelong dream to go to college in the US despite never having completed high school.

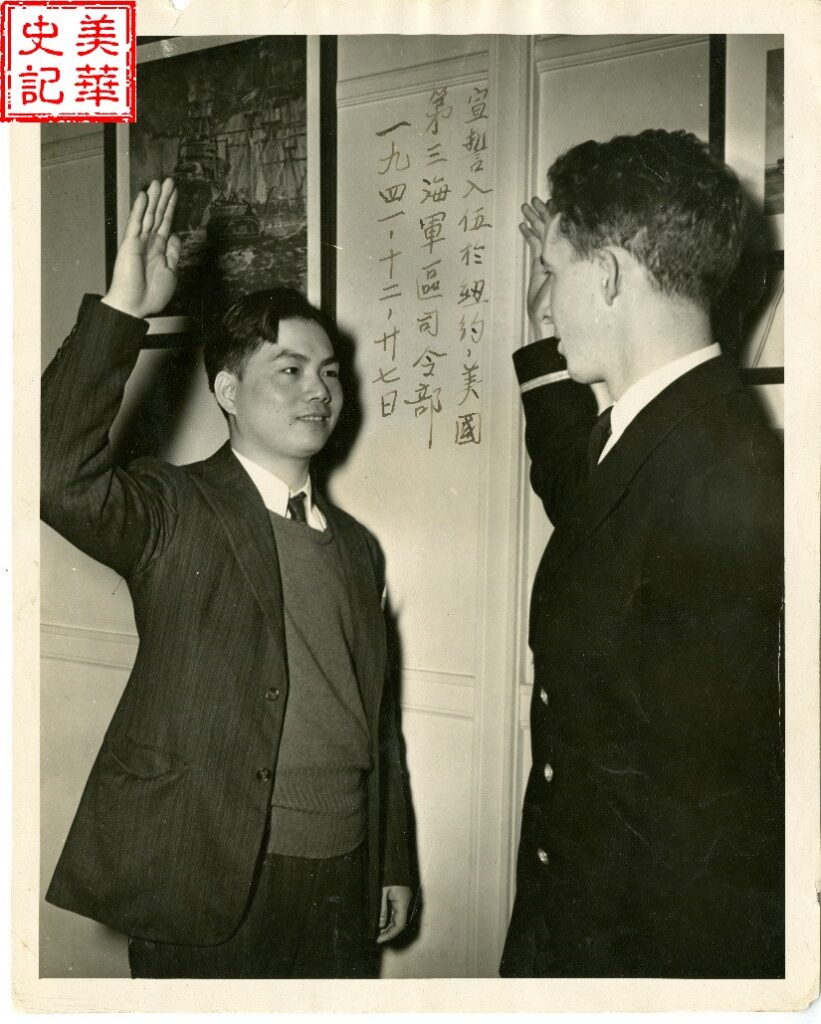

However, in 1945, Chin set off for a different course and joined the Navy. During his service, dean of education at NYU Ralph Pickett (whom Chin had been in correspondence with all year) frequently sent him grammar books and reading materials to encourage his studies. Though Chin never ended up going to college, the experience serving in the Army and Navy equipped him with countless valuable stories to write about. The discovery of this new passion sparked his works of poetry written in the style of prominent Chinese poets.

Unfortunately once again, Chin was forced to give up his dream. During the violently anti-communist era of the 1950s led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, Chinese-Americans became walking targets under fire for being suspected of supporting communism. FBI raids, blacklists, and unjust interrogations plagued Chinatown. This era of terror sparked Chin to write his memoir. Published in 2001 by the Temple University Press, this memoir illuminates the story of one little-known Chinese-American with the goal of speaking for the many other nameless, faceless paper sons and daughters and the dangers they survived in this new land.

Speaking of paper daughters, Chin’s own daughter Winifred Chin-Hing Chin co-authored the Paper Son memoir. Born and raised in the city of New York, Chin-Hing Chin mastered two languages. She learned Chinese, poetry, philosophy and history at home with her father and English at public school. Chin thought that if McCarthy’s forces would force him to be deported back to China, then at least his daughter would understand its language and culture. Fortunately, America came to its senses and the tables turned: McCarthy faced interrogation and was condemned by all.

And then it seemed that Winifred Chin was able to secure her American dream after all; she attended Brooklyn College, Seton Hall University, and New York University to study philosophy and religion. After she graduated, she taught world religions at St. Francis College. Later she taught East Asian culture and history at NYU. As the editor of her father’s memoir, the world owes her thanks for her contributions in giving a voice to Chinese-American history. Today Winifred Chin is retired in Brooklyn, New York where she is still an active member in the promotion of Asian-American studies.

Winifred Chin being interviewed for PBS Documentary Asian-Americans.

America, the so-called home of immigrants, was less than welcoming towards Chinese immigrants for most of its history. Most notably, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited Chinese workers from immigrating to the US for ten consecutive years. In fact, the Exclusion Act was the singular piece of legislation in United States history to deny naturalization to a group of people on the basis of ethnicity or country of birth. It was only sixty-one years later that the infamous act was repealed, and the United States created an annual quota allowing Chinese people to immigrate.

What exactly is a paper son?

It must be noted, however, that before the Exclusion Act was repealed, Chinese immigrants were still entering the country, albeit illegally. After all, every road leads to Rome–or the US, in this case.

This is where the term paper sons and daughters becomes relevant. Chinese immigrants would illegally enter the US with fraudulent documentation stating their relation to some Chinese person already living there. It was extremely difficult for authorities to verify the authenticity of these immigrants’ claims, so just like that, they were able to forge new identities onto these slips of paper.

Once these initial groups of immigrants moved to and settled into the States, they would take visits back to China, marrying locals and reporting to American authorities that they had children. Using these tactics, more paper identities were forged and then sold on the black market to any Chinese people that wanted to immigrate. As long as you had the money (about $3,500 according to today’s rate of inflation), you could purchase a slip of paper with a corresponding age and sail for the New World. Most immigrants, however, would pay off their debts through employment upon arrival in the States, because none besides the very wealthy could afford to pay off the debts right away.

The “paper son” practice entered an especially widespread period of use when the San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed thousands of Chinese immigrants’ birth records. This was not all bad news; like all wildfires, the destruction brought something new: thousands of Chinese immigrants were able to claim newly fabricated identities in order to create more potential “paper sons.”

In 1910 when the practice had reached new heights, the US government cracked down and built an immigration station in San Francisco misleadingly named Angel Island. Consequently, Chinese immigrants who arrived in the US from 1910 to 1940 faced severe interrogation and quarantine in Angel Island for months or even years before they could step foot into the rest of the country. Immigrants were forced to memorize years’ worth of minute made-up details with the risk that any errors or inconsistencies in their stories could lead to deportation.

In Chin’s memoir, he recalls the last time he was investigated by the FBI in 1959 in which he not only had to recall these fabricated details but also had to continue living his life like he really was the paper son that the slips documented.

Chin writes:

“I arrived in the United States in Boston, 1934, at the age of nineteen. I had purchased my “paper” in the Chinese black market that designated me as the “son of native.” As the son of a native, I was automatically a United States citizen upon verification of all the facts. In order to get all the facts straight, I studied for months while still back home: my paper name, my paper father’s name, my paper mother’s name, my age, their ages, my place of birth, their places of birth, their occupations, etc.…”

Tung Pok Chin is sworn into the US Navy, 1941.

Paper Son: One Man’s Story was and still is a rare gift for literature and history. Before this memoir, there were close to no publications about Chinese-American history written by Chinese-Americans. For example, readers are able to explore the raw and gritty, usually hidden truths about toiling away in the American laundry industry where Chinese immigrants were subject to on the East Coast. This book truly expresses the good, bad, and ugly of the Chinese immigrant experience.

The Impact of Systemic Chinese Exclusion

Chinese immigrants of the past and present aspired to travel to America for its opportunities (among other reasons). At the time, the Chinese economy was in a decline, and employment was scarce. On the other hand, the United States was developing its Western frontier and in need of workers. As Chin recounts in his memoir:

“My village was and probably still is the size of a football field, located singly in the open field, having less than fifty families. Sha-tou Ch’uen, the poorest of the poor, literally means, ‘Sand Head Village.’…Tai-shan County was unique to Guangdong Province.Before World War II more than half the heads of households in Tai-shan villages made their livings either in the United States or Cuba. My village was no exception.”

Thus it was rumored that America was the land to “get rich quick.” Chinese immigrants brought with them their history, culture, and customs to this new foreign land which to this day shape the

Chinese immigrant experience. However, nothing more profoundly impacted those

Chinese-Americans’ experiences more than US immigration policy that banned the Chinese from entering the country from 1882 to 1943. Only after the United States and China allied during World War II did the US lift the policy. Even then, the quota for Chinese immigrants was a mere 105 per year.

Among the Chinese immigrants that entered the country during the time of Exclusion, the men outnumbered women for a few reasons. First, it was the traditional belief that the men should venture overseas to work while the women managed the household back home. Second, Chinese laborers were not allowed to bring their wives to the country because of the US’s agenda to prohibit the growth of Chinese families in America. To further this agenda, the US prohibited interracial marriage so that Chinese men could not marry or have children with white American women, either.

But that’s not all in terms of the anti-Chinese legislation that plagued the US. Laws prohibited Chinese immigrants from working in certain occupations, leaving them positions for only the most menial, dehumanizing jobs. Chinese immigrants were also denied citizenship according to the Exclusion Act, unable to fulfill their fundamental rights of life, liberty, and happiness. The US was violently exclusionary, doing whatever it could to prevent the Chinese from assimilating into America. One cannot help but wonder once again if the words carved onto the Statue of Liberty were empty promises.

Life during the McCarthy Era (1950s)

Paper Son: One Man’s Story also records Chin’s life experience surviving through the McCarthy era. McCarthyism was the name of the movement used to describe the violently anti-communist era during the 1950s, led by Senator McCarthy in which every citizen, immigrant, and alien faced groundless accusations, unfair investigations, and ruthless persecution if found “guilty of supporting communism.” The FBI kept an especially close watch on the Chinese community living in America. For the paper sons and daughters especially, Chinese immigrants felt the danger and tension whenever the FBI came barging into their homes and workplaces. Chin was also worried that the poetry he published in China Daily would be perceived as supporting communism because it was allegedly left-leaning.

Despicably enough, the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) began encouraging illegal Chinese immigrants to confess their illegal statuses and expose other paper sons and daughters in exchange for a legal immigration status. Now, there was not only tension and mistrust with the United States government, but the Chinese immigrants were becoming mistrustful of one another as well.

Chin and his wife chose not to confess their forged identities, a source of anxiety that kept him and many other Chinese immigrants feeling unsafe and in danger at all times.

Chin working alone in his laundry shop

Chin wrote for China Daily News and worked with its former editor-in-chief (Tang Mingzhao, member of China’s first delegation to the United Nations whose daughter was former President Nixon’s translator on his official visit to China). Tang Mingzhao was suspected of having ties to the Communist Party, so Chin’s proximity to him was dangerous. Even though Chin himself served in the US Navy and converted to Christianity and worked as a translator at his church, the FBI still found a “reason” to investigate his laundry shop. The FBI even went to Chin’s son’s elementary school to force his child to confess. Fortunately the school’s principal and teachers protected Chin’s son, rendering the FBI’s attempts unsuccessful.

China Daily was accused of violating the “Trading with the Enemy” Act because the newspaper published advertisements encouraging Chinese-Americans to send remittances home through certain Chinese banks. Eugene Moy, succeeding editor of China Daily Newswas at the time, was sent to prison.

Chin went to further lengths to appear more “American.” He subscribed to the New York Times, burned all the Chinese poetry he wrote and published, and wrapped his Chinese newspapers around American newspapers before discarding them forever.

Merchandise in stores was not safe, either. People were afraid of selling products that had the label “Made in China” for fear that even the association with the word “China” would cause suspicion within the US government.

To avoid being “guilty by association,” Chin also stopped correspondence with his American mentor Dr. Ralph Pickett.

During this age of mass paranoia, Chin compared the Chinese living in America during the

McCarthy era to the Japanese living in America during World War II. He writes in his memoir:

“I compared my situation with that of the Japanese during World War II. The United States not only declared war on Japan, but also on Germany and Italy, yet no Germans or Italians were rounded up and routed to internment camps. To add insult to injury, many of the elderly Japanese men who were detained during the Second World War had fought for the United States during the First World War! Now, only a few years after the war, I feared McCarthyism would similarly strike out against the Chinese people on account of China; for although the Japanese were not our only enemy, they looked different and could be easily set apart. So it was that after the

Second World War many nations in Eastern Europe had turned to communism too, but we Chinese could be set apart by our appearances and by our names, and so, as the theory went, one had to be wary of all Chinese.”

As his anxiety continued to grow, Chin sought the advice of his pastor. His pastor told him to stay cooperative with authorities, stop writing, and to maintain a low profile–in other words, to remain complacent and unnoticed.

In Chin’s memoir, he recounts the experience of another laundry shop owner that he knew, Mr. Wong, who also entered the US as a paper son in the 1930s. Wong’s shop was savagely searched and his life was uprooted. Chin writes:

“But now, everything was all over the floor, all mixed up. Every corner of every shelf, every corner of the floor under the boards, and anything that could be moved was cleared out as possible hiding places.”

Chin recounts Wong’s words to him:

“‘ I’ve done nothing wrong. I was so proud, you know, when our first daughter was born here right here on Gold Mountain soil!’ His eyes filled with tears as he looked back at those precious moments and then looked up again at his present surroundings. ‘What do they think a poor laundry man can do? Do they really think I run a spy network out of this little storefront?’”

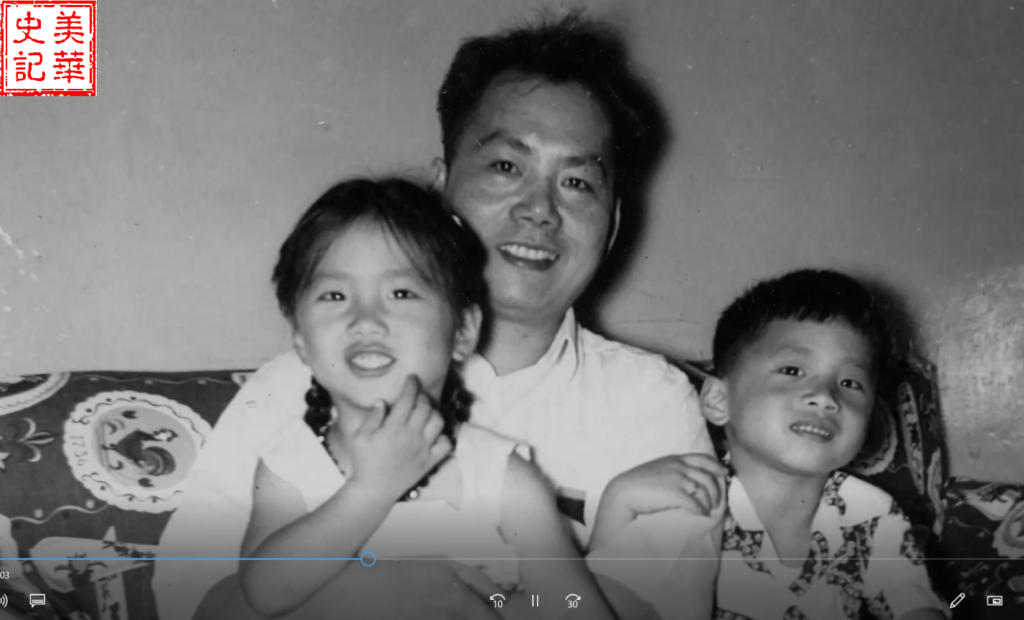

For fear of deportation, Chin taught his children the Chinese language and Chinese culture so that in case they were banned from the US, his kids could assimilate more easily in China. Fortunately, this turbulent era of mass hysteria and ruthless persecution ended. Chin’s last FBI visit was in 1959. He writes in the last line of his memoir:

“That was the last time I was questioned by the FBI. Perhaps they finally realized that I was just a harmless poet trying to make a living for my wife and family here in Gold Mountain.”

Chin and his children.

References:

1. Paper Son: One Man’s Story by Tung Pok Chin and Winifred Chin

2.A Life on Paper by K. Scott Wong

Tung Pok Chin was kidnapped as a child by the Lai Family, not Chan — a minor error early in this synopsis. All else is accurate and well-written.