Author: Xin Su

Translator: Rosie Zhou

ABSTRACT

On May 19, 1975, New York City’s Chinatown witnessed the largest demonstration in its history – a protest against the beating of Peter Yew, a 27-year-old engineer from Brooklyn, by police officers of the Fifth Precinct in Chinatown. After several weeks of protesting, all charges made against Peter Yew were dropped.

Introduction

Being a police officer is a dangerous profession. Police constantly live on the edge in order to maintain public order. When people gain a sense of security from a stable order, they feel a sense of respect and gratitude towards the police – especially the Chinese! The traditional values that Chinese people possess originate from Confucianism, which has existed for thousands of years. They believe in respect and self-discipline, and use personal moral constraints to maintain social order. The United States is a country under the rule of law, and its essential cultural values include democracy, equality and freedom. The Constitution guarantees citizens the right to challenge the old order and allows citizens to express their ideas, hopes and concerns to the government through advanced democratic methods – petitioning and protesting. Through the course of over 150 years since the first Chinese immigrants arrived, the original ideologies of the Chinese have clashed with the new American culture, leaving emotional and psychological impacts. They have had hesitations and confusions, but also new understandings and insights. Historically, Chinese Americans in the United States have spurred demonstrations of differing scales to defend their rights, including protesting against police brutality towards them.

Picture 1: The “First Amendment” monument built on December 15, 1791. Photo by Robin klein. The First Amendment of the United States Constitution prohibits the U.S. Congress from making any law that establishes a state religion, obstructs religious freedom, deprives freedom of speech, violates freedom of the press and assembly, and interferes with or prohibits the right to petition the government. Passed on December 15, 1791, the amendment was part of the U.S. Bill of Rights, making the U.S. the first country to have no state religion in its constitution and guarantee freedom of religion and speech.

- The Chinese Community Protests Against Police Brutality

For hundreds of years, New York City’s Chinatown has always been a place of constant hustle and bustle. Here, hard-working Chinese ran their small businesses. Their businesses relied on accumulation year by year, day by day. Thus, they viewed time as money; a clerk’s income was often calculated by the hour, and an owner’s profit was also accumulated by the hour. Over the years, storefronts rarely closed outside of regular closing times – even for a few hours. Especially for stores that were pretty popular and the cost of not doing business could reach thousands of dollars – no one could bear losing out on profits. Over time, a common narrative formed – this group of Chinese people only knew how to make money and were somewhat isolated from the outside world, while also being complacent and indifferent to politics. Because of this, the Chinese were vividly described to have “collective aphasia.”

In this light, conflicts were bound to arise. On Monday, May 19, 1975, there was an unprecedented scene in Chinatown. Shopkeepers hung handwritten signs on their doors and windows: “Closed today to protest police brutality!” Thousands of tailors , waiters, businessmen, chefs and students stopped working, challenging their stereotypical image as silent and complacent, and gathered together to protest the brutal beating of a Chinese American boy named Peter Yew by the local police [1 ,2】.

The incident was caused by a small traffic accident. On April 26, 1975, at the junction of two narrow and crowded one-way streets in Manhattan’s Chinatown, a motorcycle owned by a Chinese man blocked a motorcycle owned by a white man. The white man was very angry, so he started his engine and hit the Chinese man’s motorcycle twice. Onlookers began to encourage the Chinese man to fight back, so he returned the aggression and hit the white man’s motorcycle twice. Seeing that the outcries around him were full of hostility, the white man tried to run away, but the bystanders refused to give up and escorted him to the Fifth Jurisdiction Police Station not far away. The white man was about to seek protection and rushed to the police station to report the incident. Then, a police officer on duty came over and violently pushed through the crowd, knocking down a 15-year-old child. At this time, Yao Yangxun (Peter Yew), a 27-year-old Chinese American student majoring in construction engineering in Brooklyn, stood up. He stopped the police’s rude law enforcement, but was violently beaten by the police on the spot and taken into the police station. In the station, he was again searched and beaten, and arrested for resisting arrest and assaulting the police officer. Finally, after Man Bun Lee, the chairman of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) in New York, and “New York China Mayor” came forward to negotiate, Peter Yew was released on bail and sent to Beekman Hospital for treatment of trauma to his forehead and other injuries, such as a sprained right wrist.

This incident of police brutality against the innocent Chinese American student aroused the indignation of the Chinese, spurring them to launch a fundraiser to seek justice for him. Legal funds donated from various sources exceeded $20,000 within a few days, and the May 19 demonstrations fueled this growing anger to its peak [2, 3].

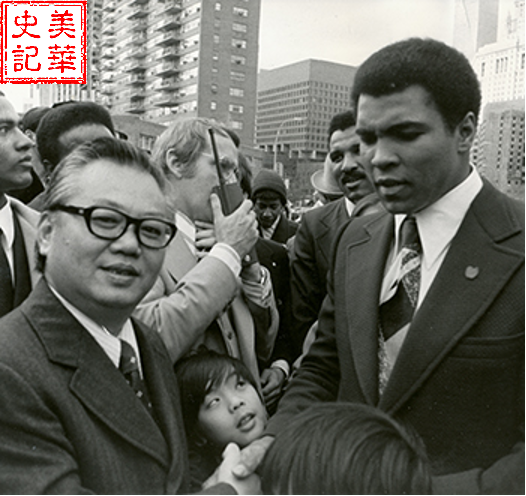

Picture 2: Li Wenbin and boxing champion Mohammed Ali. Li Wenbin was a native of Taishan. He graduated from Guangzhou University and then came to the United States. After that, he obtained a master’s degree in financial management from Tennessee State University. He was the proprietor of the Chinatown Hotel. He used to serve as the chairman of Ningyang Guild Hall, the chairman of the main branch of Lee’s office, director and honorary chairman of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, and the chairman of Chinatown Human Resources Center. Source: http://chineseamerican.nyhistory.org/man-bun-lee/

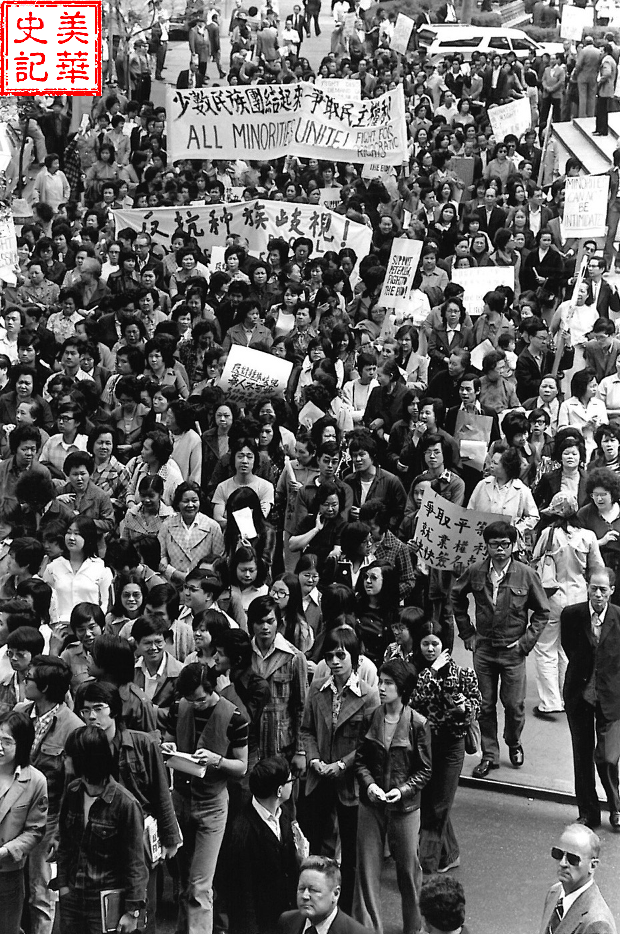

The demonstration was held under the joint leadership of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in New York and Asian Americans for Equal Employment (AAFEE). It was attended by both the elderly and the young, and even mothers with children in their arms participated. It was one of the most united and radical actions ever held by residents of New York’s Chinatown, and one of the largest protests in Asian American history – with a size of 10,000 to 20,000 people.

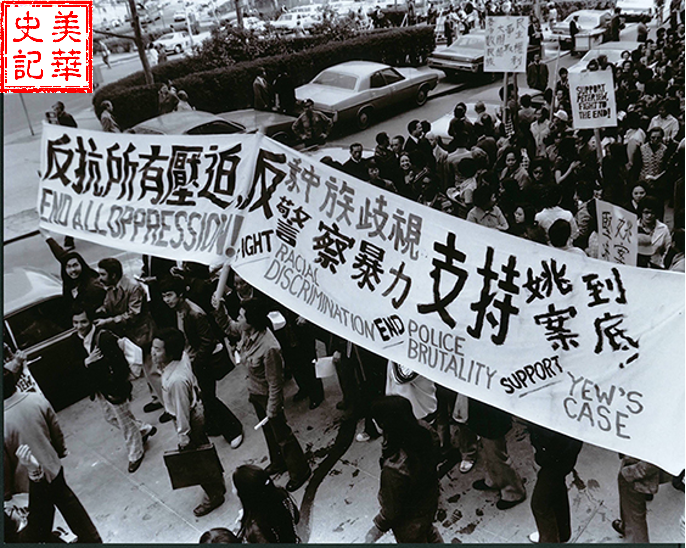

At 9 AM that day, a large number of people began to walk from Mott Street to the City Hall in a civilized and orderly manner. They picked up the garbage on the road, shouted slogans in both Chinese and English, and strictly followed the rules. “It was no ordinary family outing, people knew they were facing the police, and they were so nervous!” recalled those who participated in the march. These “silent people” who had always been timid, obedient, and lived quietly also made the calmest, yet bravest roars against police brutality [2].

Picture 3 (1): Photo by Corky Lee. Source: https://www.aafe.org/who-we-are/our-history

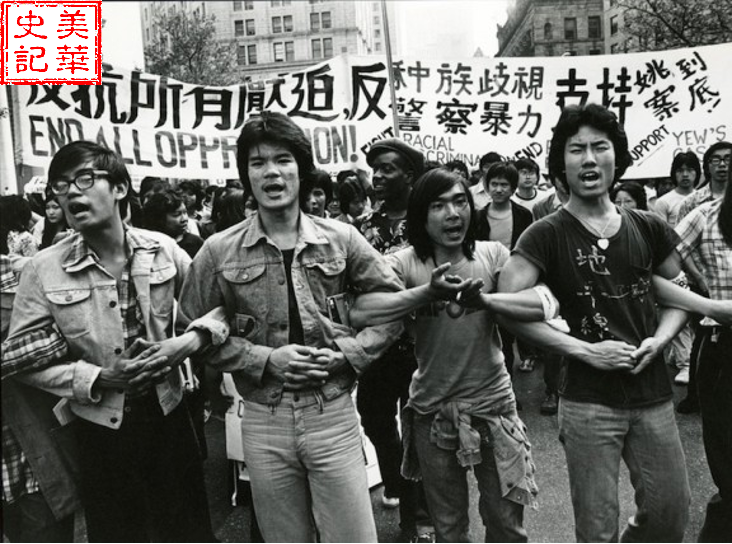

Picture 3 (2): Photo by Corky Lee. Source: Corky Lee/Interference Archives 1975

From Corky: “I know that all the guys in the front row were students from Brooklyn Tech High School. Yet the most important aspect of my photo is the Black youth in the 2nd row. He can’t believe Chinese people are protesting police brutality & that he’s in NYC Chinatown.”

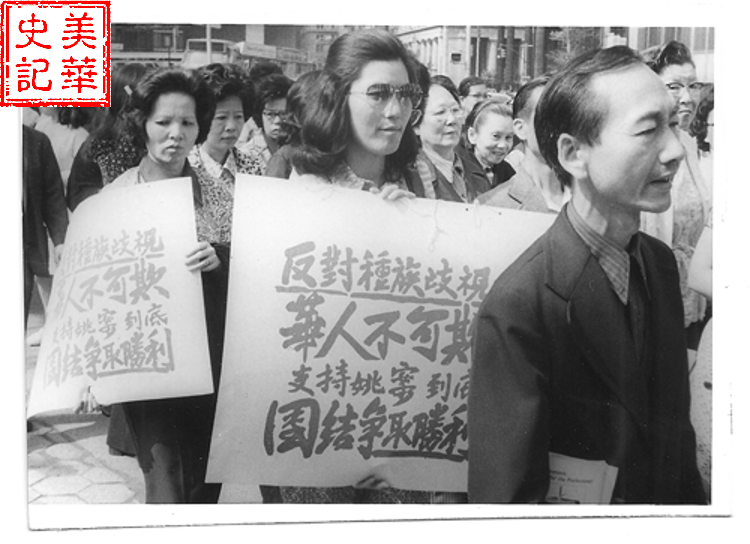

Picture 3 (3): Source: http://archivesspace.mocanyc.org:8081/repositories/2/digital_objects/158

Figure 3 (4): Protesters march with banners. The banners read “Minority Unity,” “Fight for Democratic Rights,” “End All Oppression,” “Fight Racial Discrimination,” “End Police Brutalism,” and “Support Peter Yew!” Source: https: https://www.aaldef.org/about/history/

After the parade reached City Hall, Li Wenbin, chairman of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, delivered a brief speech in which he reiterated the significance of the parade. City Hall sent Deputy Mayor James A. Cavanagh and Police Commissioner Michael J. Codd to meet with Chinese representatives who made demands to the police department – including dropping the indictment against Yew, stopping police violence against the Chinese community, expelling Fifth Jurisdiction Police Chief Edward M. McCabe, publicly apologizing for police brutality, firing the officer in Yew’s case, and more. At the same time, the Chinese also raised demands against discrimination, such as repealing funding cuts for Chinatown and calling for more Chinese to be employed in municipal jobs. After negotiations, city representatives agreed to consider the conditions and pledged to respond by May 23. Li Wenbin briefly conveyed to the people the process of negotiating the demands, which was approved by the majority. He announced that the three-hour demonstration was over [2].

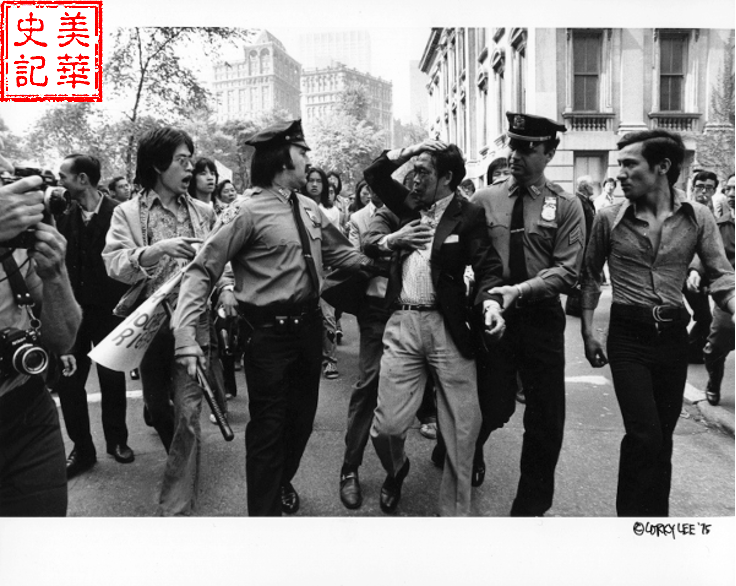

However, due to the young people of the Asian American Equal Employment Association not being allowed to participate in the dialogue between the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce and the New York City government, they were extremely dissatisfied and decided to continue the protest. As a result, a thousand people then participated in acts of civil disobedience. The rally, which had originally been peaceful, transitioned to chaos and violence by the evening. Angry demonstrators blocked the busy traffic on Broadway, clashed with the police, and some were injured in the clashes. Some protesters stayed until ten o’clock that night before withdrawing [1].

Figure 4: A bloody middle-aged Chinese man was dragged from the scene during the conflict. Photo by Corky Lee.

Source: https://hyphenmagazine.com/blog/2017/01/closed-protest-police-brutality.

In the months following this massive rally in 1975, most of the protesters’ demands were gradually met with satisfactory responses. On May 27th, Fifth Precinct Police Chief Edward McCabe was dismissed and replaced by John Ferriola. It is worth mentioning that John Ferriola visited the New York Chinese Chamber of Commerce on the first day after taking office. On July 1, a grand jury dismissed the charges against Peter Yew. The next day, a grand jury formally indicted the two police officers who beat Yew [2]. The New York Times reported the outcome of the trial on July 2 [4].

This protest by Chinese Americans not only reflected opposition against brutality of the police towards them, but more importantly, a victory against racial discrimination.

- How Protesting Against Police Brutality Developed Into a Movement Against Racial Discrimination

In the 1970s, New York was in the midst of a recessionary slump, with industries such as the garment and restaurant industries caught in a brutal price competition. The Chinese community had always been discriminated against in terms of employment, housing, education, health and other social services. Peter Yew getting beaten by the police was the last straw; after being subjected to continued racial discrimination over the past century, Chinese Americans were finally able to find an outlet to voice their economic and political grievances.

Before the Yew case, Manhattan’s Chinatown had always been in a state of self-governance. The Chinese could not enjoy justice from the law. When looking for relief or personal safety protection, instead of going to the government, they turned to gangs for help. There were sensational court battles that caused sensations in the press, but most Chinese had always been quiet and peaceful. In July 1974, the New York Police Department appointed 5th Precinct Sheriff McCabe to specialize in fighting crime in Chinatown. In his second year in office, McCabe authorized the police to conduct 11 raids on suspected gambling establishments, in which police stopped Chinese people on the road for no reason, asked them to show their ID cards, and searched their bodies. Most of the Chinese people searched were innocent.

At 1:40 am on December 3, 1974, two police officers (Heineman and Cupo) followed a group of gang members known as the Ghost Shadows into the Jade Chalet restaurant (199 Worth Street). After entering, eight Chinese youths had disputes with the police officers, and the teasing gradually escalated. The police officer (Joseph Heineman) raised his gun and fired twice [5], killing 31-year-old innocent Chinese man Tsu Yi Wu on the spot. 29-year-old James Leeong, was shot in the chest and taken to Bellevue Hospital. The two, dead and wounded, were never even involved in any gang activity. Of the eight suspected gang members, four were tried in criminal court and four were tried in family court because they were under the age of 16. The attorney for the trial, David Gotlin, accused the officer of shooting while intoxicated. The incident worsened the relationship between the Chinese and the police and triggered some small-scale protests [1, 5].

Sheriff McCabe took no responsibility for the law and order of Chinatown – he had never even visited Chinatown before the Yew case. Sheriff McCabe brushed off the Chung Wah Association’s suggestion to establish vigilance in Chinatown. Not only that, police officers had been harassing local residents [2]. The relationship between the police and the residents of Chinatown was extremely tense, and on top of that, the Chinese had endured dissatisfaction with security, housing, employment and social mobility for too long. Peter Yew’s beating finally ignited flames of anger in the Chinese community. The protest was not only against police brutality, but also detonated long lasting resentments about racial discrimination.

- Diverse Chinese Political Groups Promote the Progress of Ethnic Civil Rights

The Chinese Chamber of Commerce in New York, an alliance of more than 60 conservative enterprise groups, was the absolute leader of Chinatown at that time. In this protest against police brutality, the younger generation broke the hegemony of the old system and formed a diverse political group of Chinese Americans.

At the beginning of Peter Yew’s incident, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in New York was worried that such brutal protests would lead to friction with the city government, so they did not plan a large-scale demonstration and protest. They did nothing more than notify the city’s Human Rights Committee about the incident, raise the issue with the municipal government, apply for the dismissal of the police officer involved in the case, etc. [2].

The Asian American Equal Employment Association was established in 1973 by Japanese and Chinese Americans with a “martial” spirit. The association aggressively promoted equal employment opportunities, and even hoped that by taking actions and inciting conflicts, they could attract the attention of society and raise awareness about problems facing the Asian American community. They opposed all injustices against Asian. Previously, they fought tirelessly against DeMatteis Company for employment opportunities for Asians in the Confucius Building project. The Confucius Building Project was a federally funded housing project that provided low and middle-income apartments in Chinatown and the Lower East Side [6], but DeMatteis, the company that undertook the work, did not employ any Asian workers. Members of the Asian American Equal Employment Association jumped over the fence at the construction site to interfere with construction and held a rally at the site to protest discrimination against Chinese employment.

Picture 5: There is a precious historical video on Youtube that shows Chinese youth and company personnel fighting at the construction site of Confucius Square. The two sides are clearly emotional and quarreling fiercely (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j5EB6uewb6Q).

Their aggressive approach proved to win concessions from the company – the contractor employed 27 minority workers, most of them Asian [1].

Picture 6: The Confucius Building is a magnificent building in the center of Chinatown and a cultural center for Chinese Americans, providing residents with amenities such as day care and elderly care. Source: http://wikimapia.org/3736621/Confucius-Plaza-Apartments

Peter Yew, a well-educated young man with no criminal record or gang ties, was caught, beaten, and strip-searched by the police just for expressing objections to police behavior. The Yew case gave the Asian American Equal Employment Association another opportunity to fight for justice.

Shortly after the Yew case, the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce convened a planning meeting for the incident. Young people from the Asian American Equal Employment Association participated in the May 6 meeting of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, where they proposed a May 12 demonstration. The Chamber of Commerce did not expect the public to pay so much attention to the Yew case, and more than 600 people came all at once. There was unanimous approval for the Asian American Equal Employment Association’s march proposal. Because it was too hasty to apply for a meeting permit from the municipality, Li Wenbin, chairman of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, convened an emergency meeting again on May 7 and decided to postpone the demonstration to May 16 [2].

However, the Asian American Equal Employment Association refused to postpone the rally, and organized the protest on its own without the participation of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce. On May 12, a rally organized by the Asian American Equal Employment Association, which unexpectedly drew around 2,500-5,000 people, was widely reported in the New York Times. Municipal representatives met with young association representatives. The unified leadership of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce had been challenged by the younger generation and was in jeopardy.

On May 14, the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce held another meeting and officially announced that it would launch a larger-scale protest [1, 2]. There is no doubt that the Asian American Equal Employment Association had injected a stimulant in the Chinese struggle for justice and rights in Chinatown, and the May 12 march fostered public opinion for the May 19 march, accumulating even greater force and power. From the incident of the Chinese community’s resistance to police brutality in New York City, we can see that the two distinct groups – conservatives who abided by the rules of the game and radical youth who bravely broke through and challenged the status quo, were able to collaborate with and support each other, leading to an ideal end result.

There was a lot of debate in the Chinese community about radical young people. Some said, “Don’t make trouble…it could hurt our future.” Others even said, “This is not our country.” However, a new generation took a different view, saying, “This is our country. We have equal rights. We are going to fight for equal rights.”

Conclusion

Freedom is the basic guarantee of civil rights, and the American people cherish freedom. There will always be differences of ideas, political demands, and even fights, among the Chinese American community. However, diverse and inclusive Chinese political groups use their rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution to actively participate in civic politics and jointly promote the advancement of civil rights. They are constantly exploring ways to promote social justice in this new order and new era.

References:

1. Ryan Lee Wong. Closed to Protest Police Brutality. Mobilizing Early Asian America. January 8, 2017. https://hyphenmagazine.com/blog/2017/01/closed-protest-police-brutality

2. Yawsoon Sim. A Chinaman’s Chance in Civil Rights Demonstration: A Case Study. April 23-26, 1980. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED190684.pdf

3. May 19, 1975: Peter Yew/Police Brutality Protests. Zinn Education Project. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/chinatown-police-brutality-protests/

4. Deirdre Carmody. The Case That Stirred Chinatown is Dropped, New York Times. July 2, 1975. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/07/02/archives/the-case-that-stirred-chinatown-is-dropped.html

5. Edith Evans Asbury. Police Officer Kills a Bystander in Chinatown Melee. New York Times. Dec. 4, 1974. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/04/archives/police-officer-kills-a-bystander-in-chinatown-melee.html

6. Ground Is Broken For Huge Project Serving Chinatown. New York Times. Sept. 12, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/09/12/archives/ground-is-broken-for-huge-project-serving-chinatown.html