Author: Annette Chan, Ph.D.

Introduction

In December 2018, the Chinese American World War II Veteran Congressional Gold Medal Act was signed into law. This act awarded a medal to Chinese American veterans in recognition of their tremendous service to the United States during World War II when they and their families faced discrimination and institutional racism at home. The following is an account of how members of my family came to receive the highest civilian award given by Congress.

The Chinese Fishing Village

In the early 1850s, a thirty-foot long Chinese junk, braving the cold, rough waters of the Pacific, arrived on the shores of Monterey (Lydon 29). The boat was unusual because it contained whole families, not just men. Having fled civil unrest and economic problems in their native country, the people on the ship were seeking fortune in the new state of California–the Golden Mountain. Soon, they formed a fishing village at Point Alones to harvest the riches of the sea. The fishing village eventually became the largest and most significant Chinese village in the United States at that time (Lydon 179).

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, Chinese fishermen had increasing disputes with Italian fishermen and Portuguese whalers, who competed with them for fish. Portuguese whalers would run their boats into the Chinese fishermen’s nets and use knives to cut the nets into pieces (Lydon 54). It was difficult for the Chinese to take the vandals to court because the California Supreme Court had ruled in 1854 that Chinese people did not have the right to testify against white people (People v. Hall, Traynor 2). To counter this, in March 1880, the Chinese fishermen set a trap. They had a white American hide on the bottom of one of their boats. When Portuguese whalers came up to the boat and started cutting their nets, the white witness stood up and watched the vandalism as it was occurring. The Chinese filed a lawsuit against the Portuguese whaling company with the white witness testifying during the trial. However, the suit was thrown out when the whalers’ attorney convinced the court that the witness was biased. Although the Chinese did not win the case, the fact that they were willing to pursue their legal rights caused the Portuguese whalers to stop damaging their fishing nets (Lydon 53-54).

In order to avoid further confrontations with the Italians and Portuguese, the innovative Chinese changed to squid fishing. They had observed that some species of animals were attracted to light. At night, the Chinese burned pitch in lanterns and hung the lanterns off the sides of their boats. Squid would swim towards the light, and the fishermen would simply scoop up the squid that came to the surface. Because the Italians and Portuguese fished during the day, they no longer conflicted with the Chinese, who caught squid at night. In the 1880s to 1890s, the Chinese provided over 90% of California’s dried squid (Lydon 57).

Chinese fishing village in Point Alones. This photo is in the Hopkins Marine Station, which is located on the site of the former fishing village.

In 1880, the Pacific Improvement Company bought the Point Alones village site. The Chinese fishermen always paid their rent on time, and at first, they had no problems with their new landlords (Lydon 176). However, when the train came into the area, more people moved close to the fishing village and nearby Monterey. The newcomers complained about the bad smell from drying squid. In 1905, responding to public pressure, the Pacific Improvement Company notified the Chinese that they would not renew their leases after they expired, and they were told to leave the area by early 1906 (Lydon 357-358).

After the April 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, many Chinese people from San Francisco went to the fishing village for temporary housing. Two weeks later, possibly concerned that the Chinese from San Francisco would stay permanently in the fishing village, making it more difficult to evict the fishermen and their families, the Pacific Improvement Company resumed pressuring the Chinese to leave. Then on May 16th, a fire started in the village, burning much of it to the ground. Hundreds of white spectators cheered as the fire burned. Afterwards, they began looting the homes and stores in the fishing village. No one was arrested for the looting, and the source of the fire was never discovered; however, arson was suspected (Lydon 362-366). A year later, some of the Chinese fishermen relocated to McAbee Beach, about a quarter of a mile away from Point Alones, but many left the area (Lydon 374). In the 1920s, canneries took over the village at the beach (Lydon 384).

In 1882, May Mar, a third-generation American, was born on U.S. soil into the Chinese fishing village.

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

In the year that May was born, anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States was at an all-time high. Starting in the decade before her birth, there was a severe economic downturn in the country, making it much harder for people to find jobs. The Chinese were blamed for taking employment away from whites and for other societal problems, and they were routinely harassed (Low x). All of this led to Congress passing the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which was the first law in the United States to ban people of a particular ethnicity from entering the country (Low x). Only certain groups of people, such as students, merchants, and diplomats, were exempt. The act also prohibited all Chinese from becoming naturalized citizens (E. Lee 94).

When dealing with the Chinese, political and business leaders were faced with a conundrum: they wanted to exploit Chinese labor, but they did not want Chinese people to settle in the U.S. permanently. In 1886, Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, the ninth Chief Justice of California, described constraints to Chinese immigration that would be most helpful for businesses and for the development of this country.

If they [Chinese men] would never bring their women here and never multiply and we would never have more than we could make useful, their presence would always be an advantage to the State . . . so long as the Chinese don’t come here to stay . . . their labor is highly beneficial to the whole community . . . the difficulty is that they are beginning to get over the idea that they must go back. Then they will begin to multiply here and that is where the danger lies in my opinion. When the Chinaman comes here and don’t bring his wife here, sooner or later he dies like a worn out steam engine; he is simply a machine, and don’t leave two or three or half dozen children to fill his place.

Judge Sawyer’s viewpoints were similar to those of many others at that time. They believed that Chinese immigrants were important in developing this nation, but they did not want the Chinese to actually integrate into U.S. society (C. Lee 259).

In 1892, the Geary Act extended the Chinese Exclusion Act for ten more years. In addition, all Chinese in the United States were now required to obtain certificates of residence to prove that they were legally allowed to be in the country (E. Lee 94). The Chinese were required to carry this certificate at all times. Failure to do so was punishable by deportation or one year of hard labor. As soon as this act passed, all Chinese people in the United States were considered to be in the country illegally until they obtained their certificates of residence (Hsu 36). Today, several photos of people who lived in the Chinese fishing village, possibly taken for certificates of residence, can be seen at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History.

In 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed again, and in 1904, the act was made permanent (E. Lee 95).

Farming in Sacramento

In the early 1880s, Ching Lowe, a young man in his twenties, immigrated to the United States to make his fortune. He was a farmer, and he immediately set about trying to start his own farm. However, in 1879, the California Constitution had been revised so that land could only be owned by people “of the white race or of African descent” (California Constitution of 1879, Art.1, Sec. 17). Later, the California Alien Land Act of 1913 prohibited people who were ineligible for citizenship (such as Chinese from China) from owning property or leasing property for more than three years at a time. By preventing the Chinese from owning agricultural land or having long-term leases, the law discouraged Chinese people from immigrating to America, and it made the environment even more unwelcoming for immigrants who were already living in the country.

Undaunted, Ching leased 29 acres of land on a ranch in Sacramento. He grew peaches (which he sold to Del Monte Foods), apricots, and prunes. Ching could not speak English, but he knew the universal language of math. This allowed him to successfully do business with those around him, even the whites in the area.

However, it was difficult for Ching to find a Chinese woman to marry and start a family (at that time, California’s anti-miscegenation law prohibited interracial marriage, California Civil Code, Sections 60 and 69). The Page Act of 1875, as well as similar acts that were passed at that time, greatly discouraged Asian women from immigrating to the United States. On paper, many of these laws were meant to protect these women and to prevent prostitutes from entering the country. However, they often assumed that all Asian women who attempted to enter were prostitutes unless they proved otherwise (Lydon 118). Many women chose not to immigrate to the United States because they did not want to undergo humiliating questioning and invasive exams by immigration officials to determine if they were prostitutes. With very few women entering the United States, it was extremely difficult for Chinese men to start families.

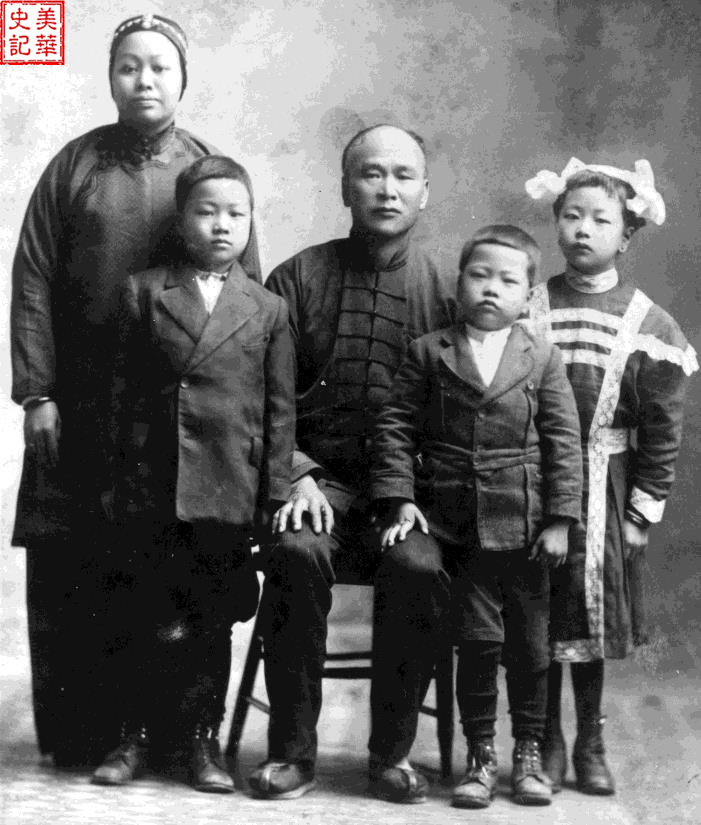

Fortunately, in his forties, Ching met and married May, possibly becoming the first man from China to marry an American-born Chinese woman. They settled in Sacramento and had six children together: Daisy, Herbert, Albert, Robert, Rose, and Gladys.

May Mar and Ching Lowe with three of their children, (left to right) Herbert, Albert, and Daisy

Education

In 1860, the California State Legislature passed a School Code that segregated certain minorities, such as Chinese, into separate schools. Then in 1870, the Legislature changed the code so that Chinese American children were not allowed to attend even separate schools. Because of this, from 1871 to 1885, Chinese children were not allowed to go to all-white or separate schools, making them the only race that was denied a public education (Kuo 193). This meant that Chinese in California paid taxes, but they did not have access to public schools. A Chinese family sued the San Francisco School District over this, and in Tape v. Hurley (1885), the California Supreme Court ruled that it was against the law to exclude Chinese American students from public schools based on their ancestry (Kuo 197). Shortly after this ruling, Andrew Moulder, the San Francisco School Superintendent, wrote, “I fear the decision of the Supreme Court admitting Chinese will demoralize our schools. But the one remedy is for the Legislature to declare urgent the passage of the bill . . . to establish separate Chinese classes. Without such action I have every reason to believe that some of our classes will be inundated by Mongolians. Trouble will follow” (Low 66). The California State Legislature amended the school laws so that Chinese American students would be segregated into “separate but equal” schools, similar to the effect of Plessy v. Ferguson over ten years later in 1896. If a separate public school were available, Chinese American students were required to attend that school (Kuo 198). In Lum v. Rice (1927), the United States Supreme Court affirmed this by ruling that excluding a Chinese child from white public schools because of race did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (Kuo 204).

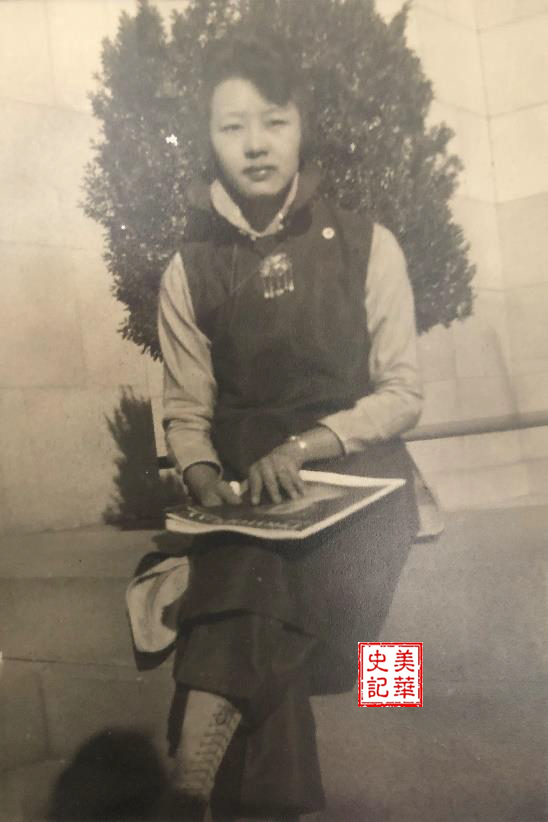

Possibly because of these onerous laws, May and many other Chinese people of her generation did not go to school and never learned to speak English, making it harder for them to assimilate into American society. However, May’s oldest daughter Daisy, who was born in 1901 in Sacramento, did attend school through the 8th grade, and she learned how to read, write, and speak English.

Daisy Lowe

Marrying Chinese

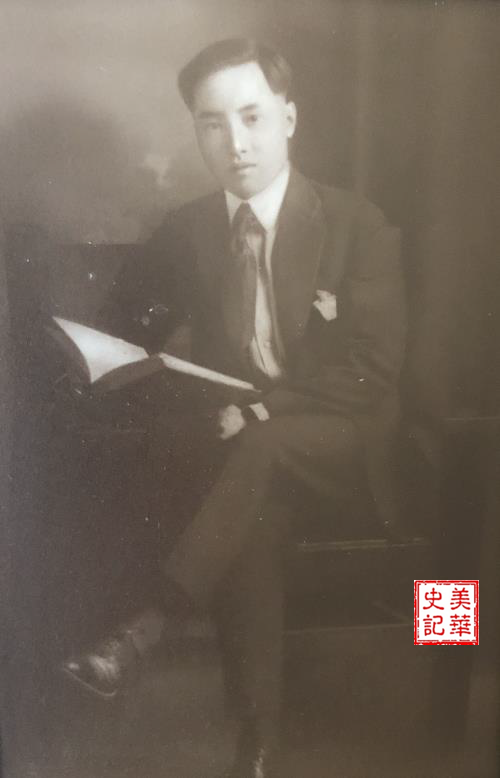

In 1926, Daisy married Chester Chan, a merchant from China, whose own father had come to California years earlier to work in Locke, one of the oldest rural Chinatowns in America. The Chinese in Locke built hundreds of miles of levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, converting it into one of the richest agricultural areas in the country (Gillenkirk and Motlow 18). After working in Locke for a period of time, Chester’s father returned to China, where Chester was born.

Because Chester was a merchant, he was in an exempt class, according to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and he was allowed to enter the country. Even so, whenever he returned to the United States, he had to pass through the Angel Island Immigration Station, where immigration officials actively discouraged Chinese people from entering, and he had to have two non-Chinese witnesses to testify on his behalf about his merchant status and business (E. Lee 98).

Chester Chan

The 1922 Cable Act took away the citizenship of women who married “aliens ineligible for citizenship” (E. Lee 87). Because Chester had been born in China and because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prevented him from becoming an American citizen, Daisy lost her citizenship when she married Chester and thus her rights to own property, travel about freely, and even vote.

Eventually, Daisy and Chester settled in Oakland Chinatown, where Chester opened a market. Because of the high levels of violence against the Chinese in the 1800s, the Chinese community in the area was segregated into Oakland Chinatown, which was an “exclusion zone” for the Chinese. If the Chinese left that zone, they were often physically assaulted.

Daisy and Chester had a son, David, born in Oakland in 1927, and twin daughters, Evelyn and Elsie, in 1929.

World War II

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Shortly afterwards, the United States declared war on Japan and entered World War II.

Despite the racism that Daisy had experienced all her life, she loved her country and wanted to contribute to the war effort. Daisy quickly went to work making parachutes for the military–a Chinese Rosie the Riveter. She also helped with wartime recruiting by assisting people from China to fill out their paperwork.

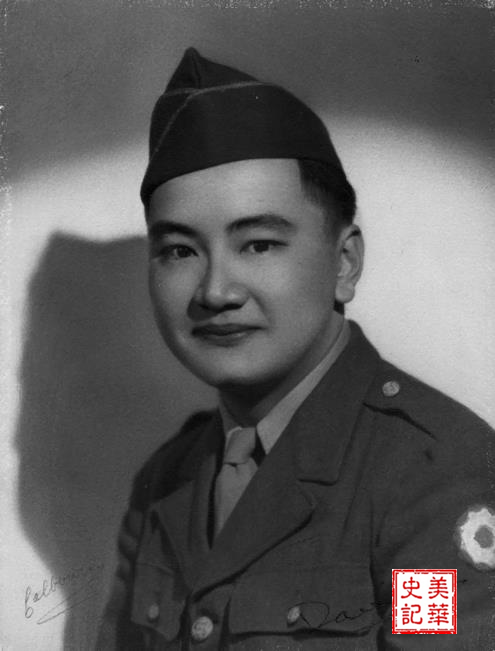

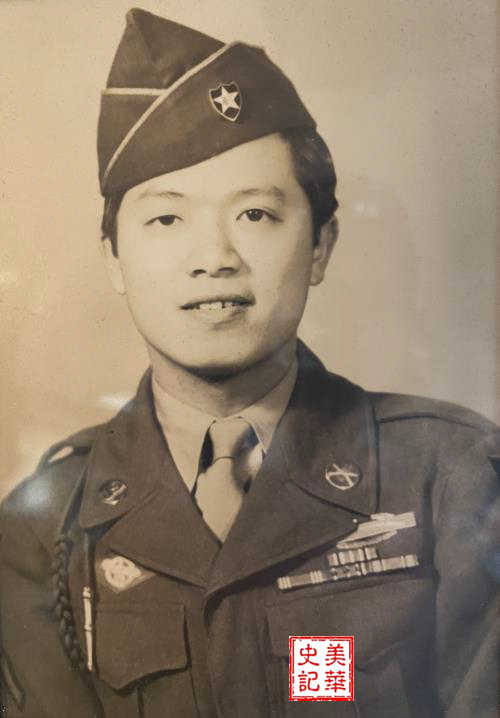

A few weeks after war was declared, David, who was 14 years old at the time, went to visit his Japanese American friend’s house in Oakland Chinatown. When he arrived at the house, he found that it was deserted. His friend had disappeared, taken away, along with his family, to an internment camp. Hatred against Asians increased rapidly. Many Chinese began wearing pins that said, “I am not a Jap,” in an attempt to keep themselves from getting beaten up by people who thought they were Japanese. When David turned 18, he received his draft papers. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and was immediately sent to basic training. During basic training, the Army discovered that David could type incredibly fast, so they decided to keep him stateside to work in their offices in Camp Beale near Marysville, California.

David Chan in the U.S. Army

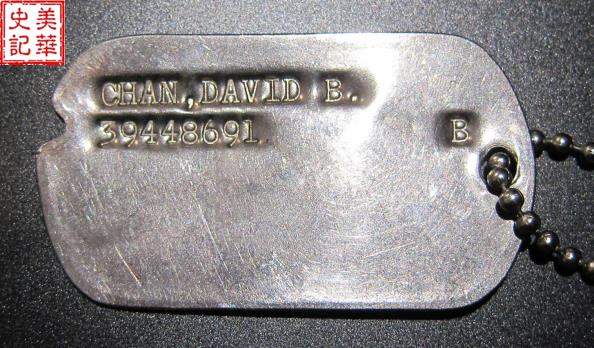

David Chan’s dog tag from WWII

Several of David’s cousins were also drafted. Shortly after graduating from high school in San Francisco, his cousin Theodore “Teddy” Wong, a great-nephew of Ching Lowe, was also drafted into the army. Teddy was sent to France and Germany, where he saw action in General George Patton’s 3rd army. Teddy’s older brother Henry Wong was also drafted and fought in Europe against the Germans.

David’s cousin Raymond Young, who was born in Sacramento and whose grandmother was May Mar’s sister, was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Force in 1943 and served in England with the Eighth Air Force–“The Mighty Eighth.” The goal of the Eighth Air Force was to gain control of the skies over Europe and allow the Allies to invade the land (Paridon). They were up against the German Luftwaffe, which had the best pilots in the world and were at the height of their strength in 1943 (Paridon). However, during World War II, the Eighth Air Force proved itself to be the greatest air armada in history (“Eighth Air Force History”). The valiant men of the Eighth earned 17 Medals of Honor, 220 Distinguished Service Crosses, and 442,000 Air Medals (“Eighth Air Force History”). However, they also suffered heavy losses. About half of the U.S. Army Air Force’s casualties were from the Eighth, including more than 26,000 dead.

Raymond Young in the U.S. Army Air Force

The Story of Kenneth Mar

In March 2021, I had the pleasure of speaking with my Uncle Ken (age 96) at length about his service in the U.S. Army during World War II. This is what he told me.

In the fall of 1939, Kenneth Mar, only 14 years old, immigrated by himself to the United States. Two years later, he was watching Gone with the Wind in a movie theater on K Street in Sacramento when it was announced that Pearl Harbor had been attacked (Wong). When he turned 18 and was in his second year of high school, he was drafted into the United States Army. It did not matter that he was not a U.S. citizen; the military needed personnel.

After basic training, Ken was sent to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, the embarkation point for those being sent overseas to Europe. The day that he arrived in Camp Kilmer was D-Day, June 6, 1944, when Allied forces invaded Normandy. He boarded a ship to England and then took another boat across The Channel into Omaha Beach in France. As he walked up a bluff on the beach, he could hear artillery and small arms fire in the distance, and he wondered what he had gotten himself into.

Kenneth Mar in the U.S. Army

Ken had been assigned as a replacement for the 2nd Infantry Division because it had suffered high casualties in the Battle of Normandy. As far as he could tell, he was the only Chinese person in the company. Their job was to liberate Brest, France, which was still in German hands. Because Brest was a vital port city, Adolf Hitler had ordered his men to defend Brest “to the last bullet” (Lengel). On a hill overlooking the city, they dug foxholes, preparing for the Germans to attack. As soon as Ken laid down in his hole, a mortar shell hit right next to him, showering him with dirt and nearly burying him. A fellow soldier standing near him was badly injured. The soldier was taken away to an aid station where he later died. The next day, the 2nd Infantry Division fought its way into Brest. After days of fighting and almost 10,000 American casualties (Lengel), the city of Brest was liberated, and Ken had survived his first combat mission.

Ken Mar’s journey across Europe: 1 – The English Channel (The Channel), 2 – Omaha Beach, 3 – Brest, France, 4 – Paris, France (Ken passed through Paris by train on his way to the border between Belgium and Germany), 5 – Verviers, Belgium, and 6 – Limburg, Germany.

After the Battle for Brest, Ken and his fellow soldiers were placed on a train and headed east to the border between Belgium and Germany. The Germans had sustained heavy losses, and the Allied forces felt confident that they would win the war, possibly as soon as Christmas (Huxen). By the time they reached the border, it was wintertime. There was a little snow, and it was getting colder. To sleep, they would simply dig a hole, lie down in it, and put something over the top. It was so cold that Ken became ill. After developing a fever, he was sent to a hospital in Verviers, Belgium.

Then on December 16, 1944, while Ken was at the hospital, the Germans launched a surprise attack against the Allied forces. Hitler wanted to use his forces to break through a weakly defended area of the Allied lines in the forests of the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg. They planned to capture Antwerp, which was an important port city that supplied the Allies with food and ammunition, split apart the British and American armies, and systematically destroy both of them (Huxen). This was the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, a massive, last ditch effort by a desperate enemy.

Ken had been in the hospital only two days when the battle started. He was told that they needed his help back at the front. As soon as he was better, he was placed on a truck with several other men and taken back to his division. When he arrived, he noticed that many of the people that he had fought with were gone. They had been either killed or captured.

The weather was now very bad with heavy snow and bitter cold. Some people died from the cold. If their feet got wet, their toes would freeze and lose circulation, leading to trench foot and sometimes amputation. Fortunately, Ken managed to keep his feet dry.

He and the other men in his division bravely fought the Germans, chasing them back into Germany, one town at a time, until they reached a thick forest near the border of Belgium and Germany. They could see several German dugouts at the edge of the forest. With a Sherman tank leading the way, they drove the Germans out of the forest. The next day, they planned to gain control of a highway that was just beyond the forest. It was getting dark. Ken and another man walked into a German dugout, which was still warm. The two of them were tired and cold. They sat down, and soon, they fell asleep.

Early in the morning, a soldier from a nearby foxhole jumped into their dugout and told them that they had to leave immediately. The Germans had returned to attack them. They followed the man to another dugout. A soldier was lying dead there. Ken saw that there were only four of them left, but they had to somehow stop the Germans. One of them raised his head out of the dugout to take a shot at the Germans, but a machine gun sent a bullet through his head, killing him instantly. Suddenly, Germans surrounded them, and they were captured.

The Germans walked them back to Germany. When they left the forest, more prisoners joined them. They were taken to a farmhouse that had been converted into a temporary prisoner of war camp, and they were held captive there for a month. The camp was so unsanitary that at least six people contracted diphtheria and died. The Germans then transported them to Stalag XIIA, a prisoner of war camp in Limburg, Germany. Ken could hear artillery fire in the distance, and he was hopeful that the Americans or perhaps the Russians would soon liberate them. Two weeks later, the German guards walked them out of the camp and took them to a small German town. Then the guards disappeared, leaving them alone with the townspeople. Soon after that, an American tank came rumbling down the street, and Ken was liberated.

The Battle of the Bulge lasted until January 25, 1945. There were over 80,000 U.S. casualties, including 19,246 dead and over 23,000 men captured. About 10% of all of the U.S. casualties of World War II occurred during the Battle of the Bulge (Huxen). But Ken Mar survived, later receiving a Bronze Star for his heroism and a European Campaign Medal.

After the War

After the war, David Chan received his undergraduate and doctoral degrees in history from UC Berkeley. He eventually taught American history and Chinese history at Cal State Hayward (now Cal State East Bay).

In 1946, Teddy Wong was honorably discharged from the Army with the rank of Sergeant. He became a prominent businessman and co-owner of Town & Country Market in Porterville, California, with his brother Henry Wong, employing more than a thousand people at their store over the years. He was a community leader and philanthropist, and he founded the Chinese Cultural Center in Visalia (Elkins).

Raymond Young worked 37 years for the U.S. Civil Service as an Aircraft Maintenance Supervisor at Mather Air Force Base. He was a Master Mason for 58 years, and he was honored with the prestigious Hiram Award.

Ken Mar returned to California after the war and later worked in government service for 33 years before retiring. He currently lives in Sacramento with his wife of over 70 years, coincidentally also named May Mar. Ken was one of the ten people who were featured during the online Chinese American World War II Veterans Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony on December 9, 2020.

The Chinese American World War II Veteran Congressional Gold Medal Act

In the decades before World War II, Chinese Americans and Chinese nationals faced institutional discrimination in the United States. Alien Land Laws prevented them from owning land, and major court decisions prohibited them from testifying against white people (People v. Hall) and forced their children to attend segregated public schools (Lum v. Rice). At the start of the war, the Chinese were still under the Chinese Exclusion Act, which for over 60 years limited the size of their population and prevented Chinese people who were not born in this country from obtaining citizenship. Chinese Americans were attacked and even killed because of their race.

Despite all of this, as many as 20,000 Chinese Americans, almost 20% of the entire U.S. population of Chinese Americans at that time, served in World War II, about 40% of them without U.S. citizenship. During the war, in addition to being awarded citations for valor and bravery, Chinese Americans earned Combat Infantry Badges, Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, Silver Stars, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and even the Medal of Honor, which is the highest military award given by the United States. These men and women demonstrated loyalty, dedication, and courage as they defended this country.

For these reasons, the Chinese American Citizens Alliance (C.A.C.A.) and the National Chinese American Citizens Alliance Community Involvement Fund worked together with members of Congress on the Chinese American WWII Veterans Recognition Project to honor the Chinese Americans who served in the military during World War II. Their work resulted in the signing into law of the Chinese American World War II Veteran Congressional Gold Medal Act (Public Law 115-337) on December 20, 2018. This act awarded a Congressional Gold Medal to Chinese American veterans to recognize their service to the United States during World War II.

Kenneth Mar receiving the Congressional Gold Medal during an online ceremony on December 9, 2020

Congressional Gold Medal for the Chinese American veterans of World War II

About the Author

Annette Chan is the director of the Cell and Molecular Imaging Center at San Francisco State University. Her grandparents were Daisy and Chester Chan, and her great-grandparents were May Mar and Ching Lowe. She is very proud of her father David Chan and all of her uncles, Raymond Young, Teddy Wong, Henry Wong, and Ken Mar, for their service to this country during World War II.

Works Cited

- “California Constitution of 1879.” California State Archives, www.sos.ca.gov/archives/collections/constitutions/1879. Accessed 18 April 2021.

- “Eighth Air Force History.” 8th Air Force/J-GSOC, Official United States Air Force Website, 11 September 2006, www.8af.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/333794/eighth-air-force-history/. Accessed 18 April 2021.

- Elkins, Rick. “Businessman Teddy Wong Dies.” The Porterville Recorder, 19 September 2015, www.recorderonline.com/news/businessman-teddy-wong-dies/article_8f2c4bae-5e96-11e5-b2ca-7b86a42560e1.html.

- Gillenkirk, Jeff, and Motlow, James. Bitter Melon: Inside America’s Last Rural Chinese Town. Heyday Books, 1997.

- Hsu, Madeline Y. Asian American History: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Huxen, Keith. “The Battle of the Bulge.” The National WWII Museum, 18 December 2019, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/battle-bulge.

- Kuo, Joyce. “Excluded, Segregated and Forgotten: A Historical View of the Discrimination of Chinese Americans in Public Schools.” Asian Law Journal, vol. 5, issue 1, 1998, pp. 181-212. Berkeley Law Online Library, doi: 10.15779/Z385G39.

- Lee, Catherine. “’Where the Danger Lies’: Race, Gender, and Chinese and Japanese Exclusion in the United States, 1870–1924.” Sociological Forum, vol. 25, no. 2, 2010, pp. 248-271. Wiley Online Library, doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2010.01175.x.

- Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. Simon and Schuster, 2015.

- Lengel, Ed. “Forgotten Fights: Assault on Brest, August-September 1944.” The National WWII Museum, 21 September 2020, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/fortress-brest-assualt-1944.

- Low, Victor. The Unimpressible Race: A Century of Educational Struggle by the Chinese in San Francisco. East/West Publishing Company, 1982.

- Lydon, Sandy. Chinese Gold: the Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. Capitola Book Company, 1985.

- Mar, Kenneth. Personal interview. 24 March 2021.

- Paridon, Seth. “The Eighth Air Force vs. The Luftwaffe.” The National WWII Museum, 18 October 2017, www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/eighth-air-force-vs-luftwaffe.

- Traynor, Michael. “The Infamous Case of People v. Hall (1854): An Odious Symbol of Its Time.” California Supreme Court Historical Society Newsletter, Spring/Summer 2017, www.cschs.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2017-Newsletter-Spring-People-v.-Hall.pdf.

- Wong, Ashley. “95-year-old Sacramento Chinese American Awarded Congressional Gold Medal for WWII.” The Sacramento Bee, 9 December 2020, www.sacbee.com/news/local/article247565350.html.

Hello Annette, this was a very informative, educational and heart warming read. Thank you for taking the time and mustering the courage to share an important part of your family history and our American history.

Oh, Annette, this was a fabulous story. I wish I could write like Shapoor, but know that I have great admiration and love for your family.

Hi Annette,

You did an excellent job in writing up this very personal historical account of your family. This is such an important piece of writing that it should be widely circulated. I will forward it to people I know. Since you are an alumnus of UC Berkeley, we should at least try to publish this essay in Cal Alumni Association.

Pingback: Promoting National Museum of AAPI – 美华史记