Author: Fan Jiao

Editor: Xin Su

San Jose, the tenth largest city in the U.S., has the largest Asian-American population and is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley, with a population of 1,013,240 in 2020 (Asian:37.2%, Latino:31%, white:25.1%)。 1

However, the so-called “Chinese problem” was a very controversial topic in San Jose society in the mid-19th century. The church burned down because a pastor organized Sunday schools for Chinese children. A German-immigrated landlord was verbally abused and physically threatened for signing contracts with Chinese businessmen. On February 4, 1886, the California Anti-Chinese Annual Conference, led by the former mayor of St. Jose, was held in St. Jose with the theme, “Chinese must get out!” “, what the hell is going on here?

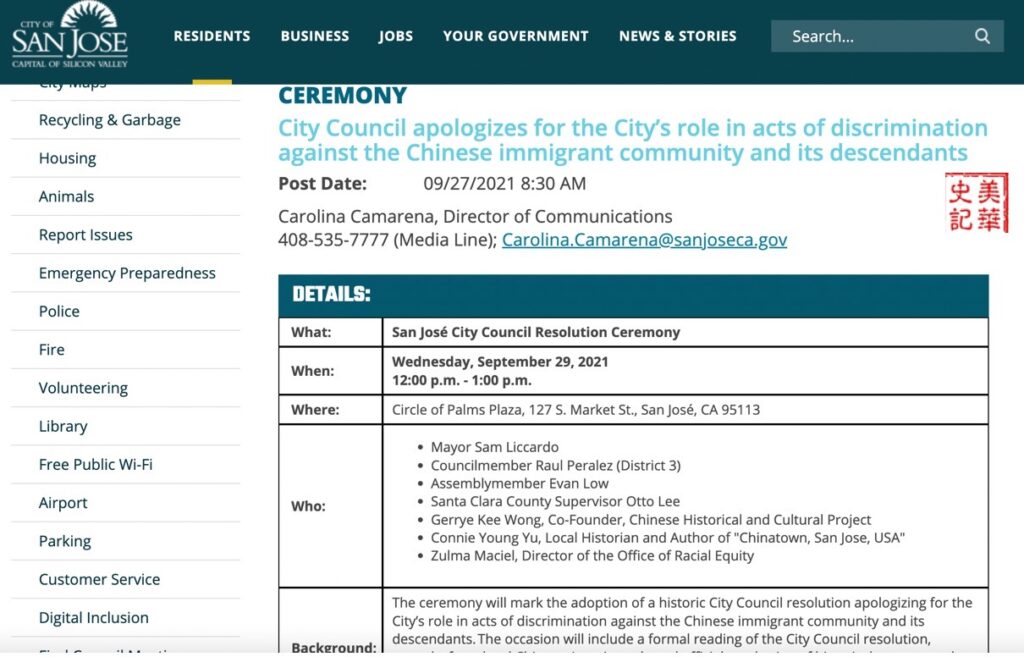

Finally, one hundred and thirty-five years later, on Tuesday, September 21, 2021, a cool and warm autumn day, the city of San Jose formally apologized to Chinese immigrants for its role in systemic racism. 2

Review of San Jose Chinatowns

More than 170 years ago, in the 1850s, the gold rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad drew thousands of people, including Chinese immigrants, to California. Many of them come to San Francisco, Sacramento, and Santa Clara, on farms Looking for work in industries such as orchards, fishing, mining, manufacturing, and laundromats. From 1850 to 1860, many people began to work on Market Street, Brokaw Road in San Jose. Settle down. 3

It is estimated that in 1880 32.8% of the entire county’s workforce in the Santa Clara Valley was Chinese immigrants.

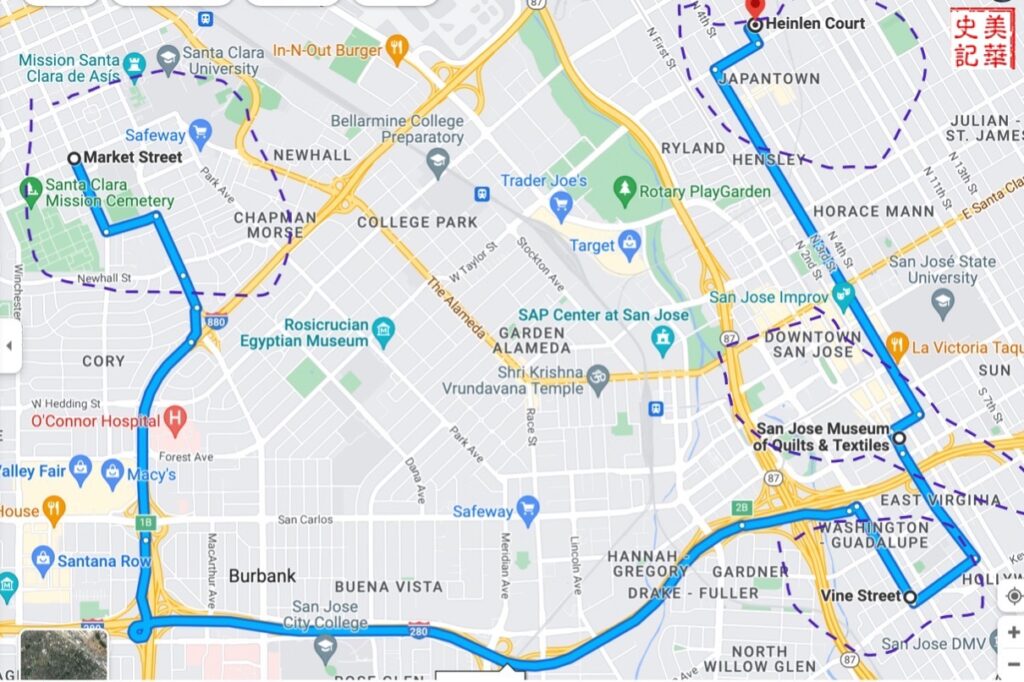

From 18666 to1931, San Jose had five thousand-seated Chinatowns 4:

1866-1870 Market Street Chinatown (burned down).

1870-1872 Vine Street Chinatown (burned down).

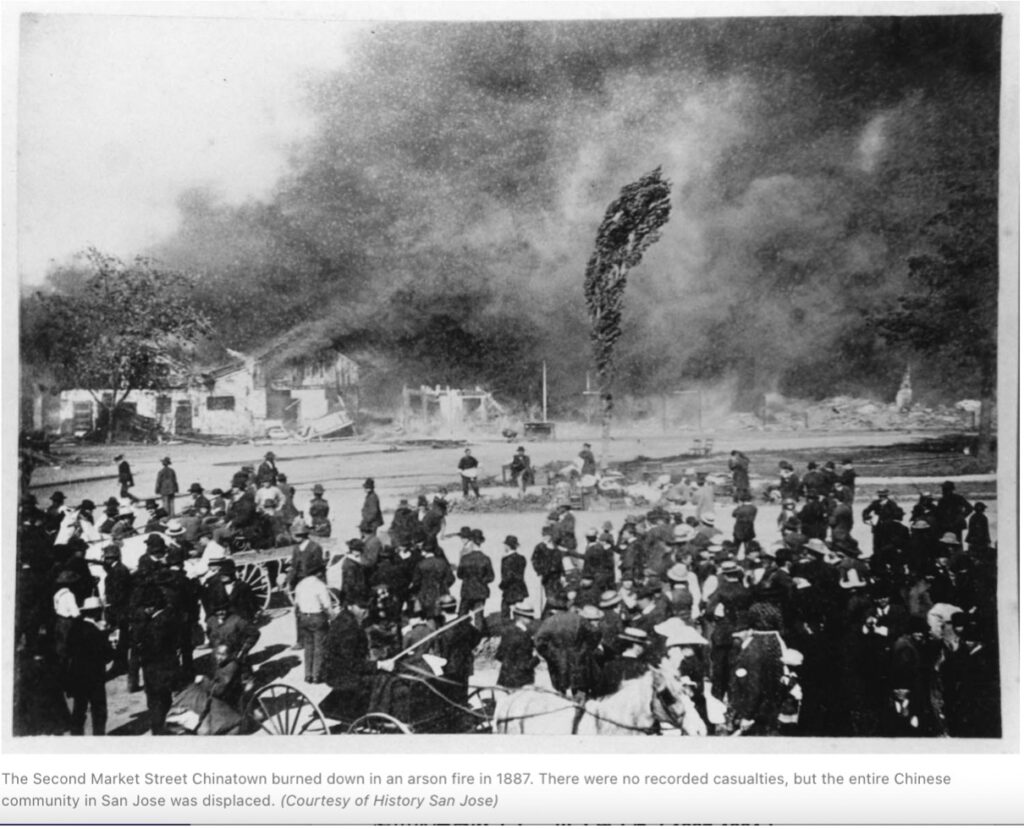

1871-1887 Second Market Street Chinatown (burned down).

1887-1902 Woolen factory Chinatown (burned down).

1887-1931 Heinlenville Chinatown (the government turned it flat because the owner could not pay taxes), and later became Japantown.

There was a lot of competition between the Chinese and the local population in industries such as agriculture, fishing, mining, manufacturing, and laundromats; in addition, due to the language barrier and different living habits of most Chinese, the relationship between Chinese and non-Chinese had always been tense since 1850s.

In 1870 and 1872 the arsonists burned down First Market Street and Vine Street Chinatown. The fire brigade did not come until the fire was largely extinguished, and the government investigation determined the fires were arson, but there were no suspects.

There were a lot of people who were happy to see every Chinatown burned down.

On May 6, 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act. Unfortunately, St. Jose had not been spared from the wave of anti-Chinese activity that had swept the West Coast since 1870. Chinatown residents were often verbally abused and being stone thrown at.

San Jose was also the birthplace of the “Buy White-Made Goods” movement, such as newspaper advertisements boycotting some fruit markets picked by the Chinese. Because of its ignorance of the Chinese and its stereotypes about them, the San Jose government at the time saw Chinatown as a “health hazard.” In March 1887, the San Jose government declared Second Market Street Chinatown a public nuisance; the measure was unanimously approved by the then Mayor Charles Breyfogle and the entire City Council; The plan would eliminate Chinatown altogether and replace it with a new town hall.

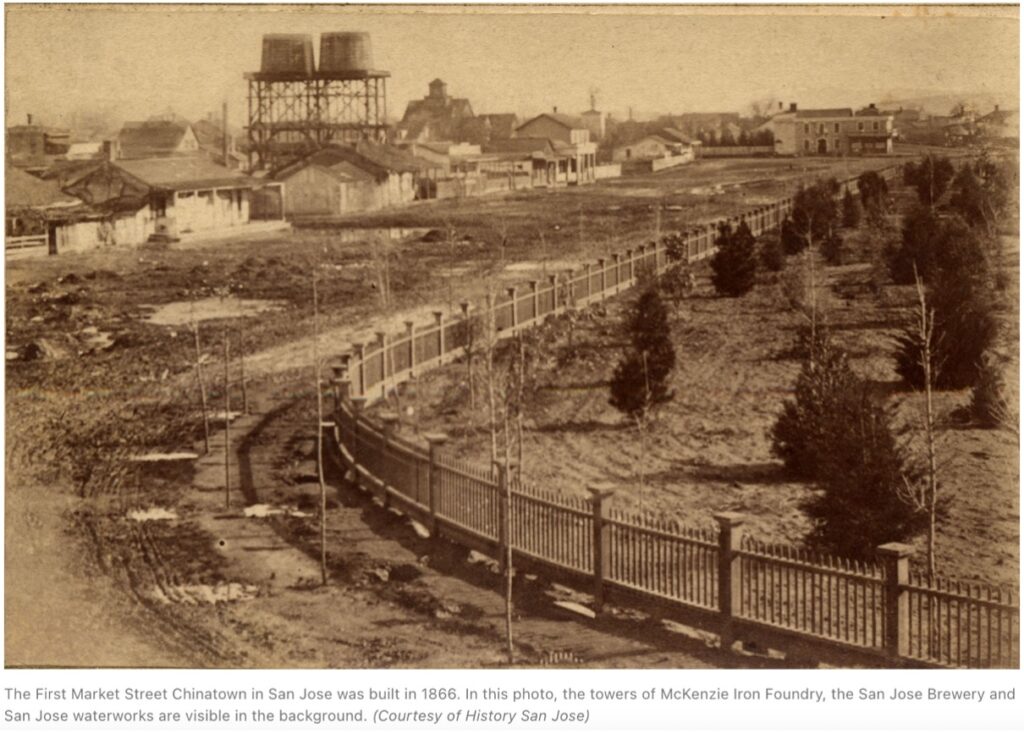

Market Street Chinatown(1866-1870)

The first Chinese settlement in St. Jose was Market Street Chinatown (1866-1870), with more than 1,000 inhabitants, making it one of largest Chinatowns in California at the time. This thriving neighborhood was located on Market Street , the corner of San Fernando Street, and consisted of about 20 apartment buildings, several restaurants, a grocery store, a laundromat, a temple, and a Chinese opera theater. 5

This Chinatown was burned down by arsonists in 1870.

Vine Street Chinatown(1870-1872)

People who survived the Market Street fires went to Vine Street and the banks of the Guadalupe River, and built several houses. This Chinatown only existed for two more years before being burned down again. 6

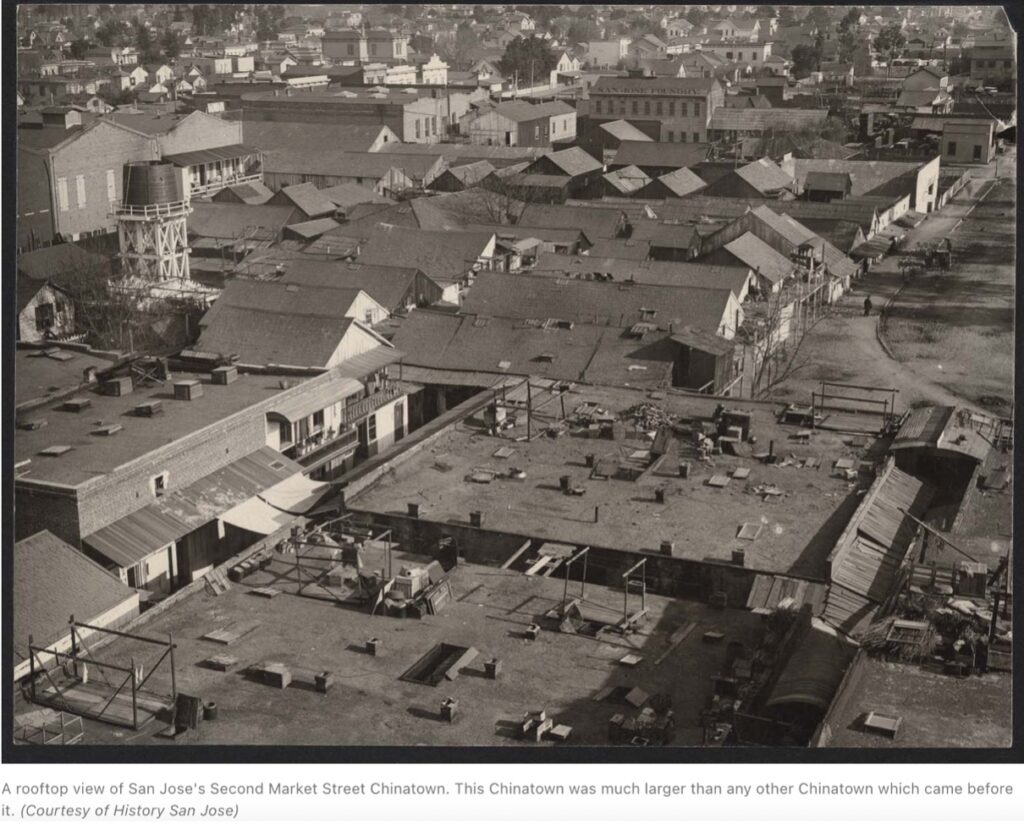

The 2nd Market Street Chinatown(1871-1887)

People who suffered from burning down of Vine Street Chinatown came here and established a new Chinatown, which by 1876 had surpassed more than 1,400 people. 7

On February 4, 1886, the California Anti-Chinese Coalition, in which Charles Breyfogle, the former mayor of San Jose, participated, held its annual meeting in Nine Counties More than a hundred delegates from Almeda, Nevada, Sacramento, San Francisco, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Mateo, Sonoma and Solano attended. In the convention’s opening statement, “whereas this Convention requires action in a nonpartisan capacity to free the people of California from the curse and suffering caused by the existence of Chinese.”

At the evening meeting, the following resolution was adopted:

“1. We see Chinese as spiritual, physical, moral, and economic evil.

2, Chinese must go!

3. Each city, town and community shall appoint a special committee in favor of the expulsion of the Chinese from all communities by all lawful means, all signatories must undertake not to patronize Chinese shops and not to purchase the products of their labor, and that the above-mentioned committees shall report to the National Executive Council the names, residences, and places of business of all non-signatories. ”8

Soon, a year later, on May 4, the Chinatown was set on fire by several fires that ignited almost simultaneously. The next day the San Jose “Daily Herald” gleefully declared, “Chinatown is dead.” It’s dead forever. ”9

A hundred years later, the flagship San Jose hotel, the Fairmont Hotel, was built on this ruin.

Woolen Mills Chinatown(1887-1902)

In the winter of 1876-1877, the U.S. Senate held hearings in San Francisco calling on “leading California citizens” to testify about Chinese immigration. The owner of this San Jose wool mill, Robert F. Peckham said he could not continue running his business without Chinese labor.

Woolen Mills was an organized planning community with a well-designed system of sewage and fire hydrants. In 1896, the plant was one of the largest in California, producing flannel, blankets, knitted underwear and men’s clothing. The plant’s success led to an increase in the number of employees from 43 in 1871 to nearly 200 in 1884, by its owner, Robert F. Kennedy Peckham provided housing for all workers. Located two blocks south of the factory, Wool Mill Chinatown was dominated by Chinese from Second Market Street. There are also some businessmen and at least one hairdresser, and some men are also employed in the Angolan glove factory and nearby farms. There is a Chinese theater, two restaurants, two temples, an office building, a laundromat, and a warehouse. 10

But a fire in 1902 destroyed this Chinatown and the woolen mill factory itself.

Heinlenville Chinatown(1887-1931)

John Heinlen was a German immigrant, a former farmer in Ohio and Indiana, who was discriminated against by anti-German prejudice and discriminations. So, he sympathized with the Chinese, hired Chinese, and leased his land in the Fresno estate to Chinese. He felt that the Chinese should have a community of their own so that their population could thrive, hence the 1887 After the Second Market Chinatown fire, he rented a piece of land for the Chinese and asked an architect to design a house and a wall separated from the outside world. This neighborhood has since been known as Heinlandville Chinatown. For this reason, he and his family had been subjected to many threats and abuses. 11

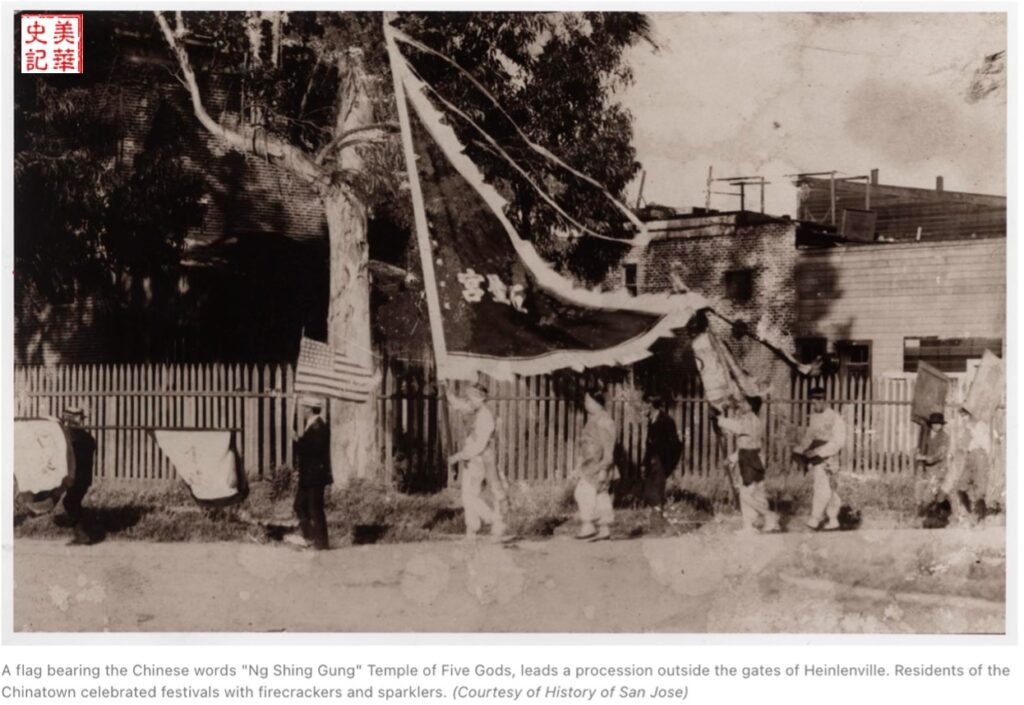

In the early 20th century, Heinlenville was a center of San Jose-Chinese business and cultural life. Despite their poverty, the people of Heinlenville donated the income they received from their humble jobs to their highly respected Ng Shing Guan, a community center and chapel.

Initially, the fence around Heinlenville was locked every night for the protection of residents. Eventually the community grew to about two thousand people. As the town prospered, the gates remained open.

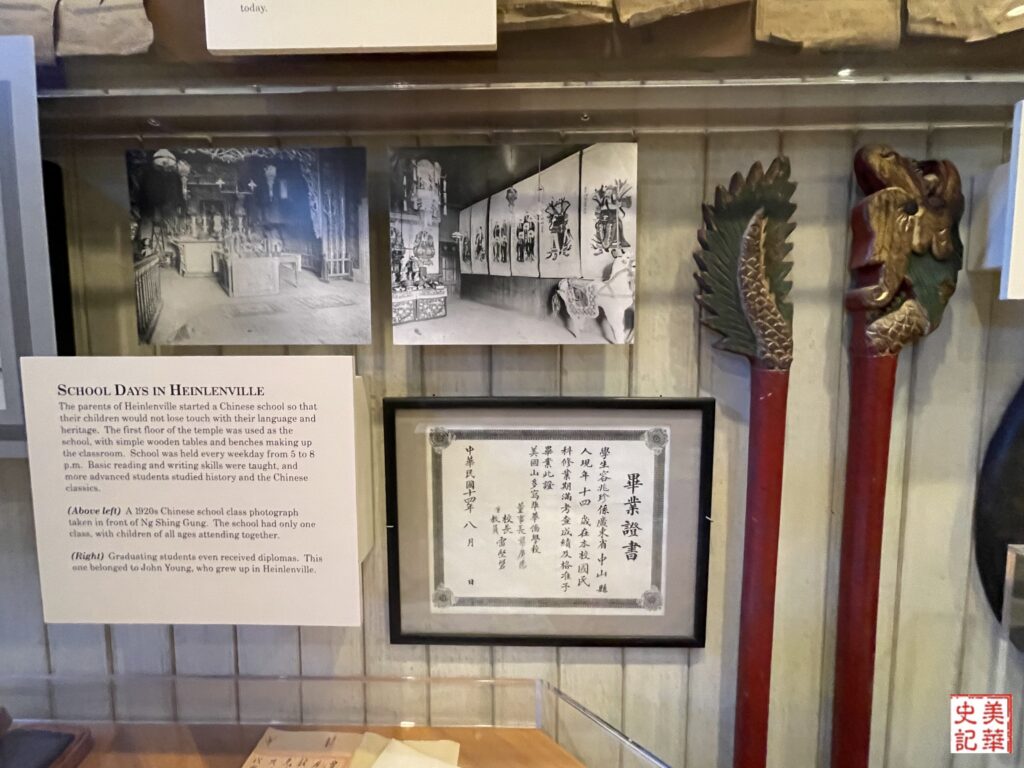

Heinlenville Chinatown survived the 1906 earthquake and prospered until the 1930s. It’s after school programs, shrines (Ng Shing Guan’s second floor), shops, etc. all allowing children (including girls) to be raised in the traditional Chinese way.

At the same time, Heinlandville Chinatown was gradually influenced by Western religion and culture. Some attended Christian churches, and women began to work, shouldering the burden of life with men. During World War I, many Chinese women participated in the volunteer work for the American Red Cross.

John Heinlen died in1903. His descendants went bankrupt during the Great Depression, could not pay rent, and Heinlenville Chinatown declined. In 1931, the estate went bankrupt and Heinlenville became the property of the city. All the buildings were eventually demolished.

In addition, in the 1890s, some Japanese immigrants settled near Heinlenville and built a Japanese settlement on its edge, which grew westward from Heinlenville. After World War II and after the unfortunate internment, those Japanese came back, and the area was officially known as Japantown.

Fairmont Hotel

In the mid-1980s, construction began on the San Jose flagship hotel, Fairmont hotels, and the Silicon Valley Financial Center. During the excavation of the foundations, some 18,000 old artifacts from Market Street Chinatown were unearthed and sent to warehouses.

In 2002, Stanford University’s Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project rediscovered the 18,000 artifacts, inspiring more research into these lost towns. 12

Ng Shing Guan, Chinese History & Culture Project, and History San Jose

The Ng Shing Guan (also known as the Five Temples) were built in 1888 and are in Tylor Street and Cleveland Streets, in Heinlenville, in St. Jose. The two-story brick building, about 23 x 42 feet, was built under the direction of Yee Fook. Funding for the construction came from a $2,000 donation from Heinlenville residents. 13

As a cultural center for Chinese community service, the first floor was used as a classroom to guide children in calligraphy and Chinese literature classics for after school program/Chinese School. It was also a hall for town meetings and is also used as a hotel for travelers who did not belong to any local family. The second floor was the seat of the temple and the five holy figures.

The building is named after five statues, namely Guanyin/观音, Guan Gong/关公, God of Wealth/财神, Tianhou/天后, and Huatuo/华陀, each contains and pins on the expectations and yearning of the Chinese people for a better life in the future.

In 1945, due to perennial disrepair, the government considered the building structurally unsafe and sealed with wooden planks. After all efforts to save failed, the original Five Holy Officers were dismantled.

From 1985 to 1987, many enthusiastic Chinese in South Bay began to plan the reconstruction of the Five Holy Palaces, and in 1987, the designers rebuilt a Five Saints Palace in San Jose Historical Park based on the appearance of the year. In 1991, the Chinese Historical and Cultural Association and the History San Jose held a ceremony at the San Jose Historical Park/San Jose History to celebrate the inauguration of the Ng Shing Guan/Five Holy Palaces in San Jose, which symbolized the early years of Chinese immigration, and through the ceremony, the historic site was handed over to the San Jose Municipal Government.

In addition, the San Jose Chinese Historical and Cultural Association from time to time awards the Heinlen Award to people outside the “bridge between the people” and people outside the Chinese community.

Dr. Barbara L. Voss, winner of the 2016 Heinlenville Prize, is a historical archaeologist, associate professor of anthropology at Stanford University, and affiliation with the Stanford Center for Archaeology. Since 2002, the Society has been collaborating with Dr. Voss on her research on the Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project. As a result, the Museum of the shrines and the Museum of Chinese American History showcases many research objects unearthed from Market Street’s Chinatown that are cross-referenced and coded to the Stanford digital exhibition “Here’s a Chinatown.” https://chinesemuseum.historysanjose.org/ )。 14

Conclusion

In the blink of an eye, a new autumn has arrived.

A new generation of San Jose Chinese is constantly becoming Silicon Valley’s high-tech leaders, and on the other hand, more and more of them are actively participating in community activities, try to elect to school boards, city councils, state legislators, or congressional offices.

Chinese immigrants who grew up amid tribulations in the past are becoming the fruits of the autumn harvest.

References:

- Quick Facts, San Jose city, California, U.S. Census Bureau, last accessed 3:07pm, 9/14/2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20220613145035/https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sanjosecitycalifornia/PST045221

- Olga R. Rodriguez, September 29, 2021, Updated September 30,2021, San Jose, AP, last accessed 3:12pm,9/14/2022, https://www.ktvu.com/news/san-jose-apologizes-to-chinese-immigrants-for-role-in-systemic-racism

- Chinese American Historical Museum, History San Jose, last accessed:12:58pm, 9/8/2022, https://chinesemuseum.historysanjose.org/

- Alyson Chu Yang, The history of San Jose, CA’s five Chinatowns, Jun 06, 2022, last accessed: 1:05pm, 9/8/2022, https://sjtoday.6amcity.com/chinatown-history-san-jose-ca/

- Adhiti Bandlamudi, San Jose Had 5 Chinatowns. What Happened To Them? Jun 17, 2021, KQED, last accessed: 2:42pm, 9/8/2022, https://www.kqed.org/news/11877801/san-jose-had-5-chinatowns-why-did-they-vanish

- Michael S. Chang, Ph.D., De Anza College, 16 March 1997, last accessed 3:23pm, 9/14/2022, http://apaliyla.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/9/3/13937794/150_years_of_chinese_lives_in_the_santa_clara_valley.pdf

- 国际,火燒唐人街、歧視華人移民,加州聖荷西成為全美第一個為19世紀排華歷史道歉的城市,2021/10/04,last accessed 3:32pm, 9/14/2022, https://www.thenewslens.com/article/157195/fullpage

- Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research, UC Riverside, last accessed: 1:13pm,9/9/2022,https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=DAC18860205.2.86&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1

- The No Place Project, San Jose, California, last accessed 3:37pm, 9/14/2022, https://www.noplaceproject.com/san-jose

- Lillian Gong-Guy, and Gerrye Wong, Images of America – Chinese in San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 978-1-5316-2928-1 2007, P17-P20

- lbid., P22-26

- Sue McAllister, Artifacts exhibited from a long-buried Market Street Chinatown in In San Jose, Mercury News, June 1, 2012 at 4:47am, Updated August 13, 2016 at 4:08am, last accessed 3:51pm, 9/14/2022, https://www.mercurynews.com/2012/06/01/artifacts-exhibited-from-a-long-buried-market-street-chinatown-in-san-jose/

- CHCP, 中华历史文化协会,last accessed 3:54pm, 9/14/2022, https://chcp.org/

- 中华历史文化协会,Heinlen Award, last accessed: 3:56pm, 9/14/2022,https://chcp.org/Heinlen-Award