Author: Xin Su

Editors: Qiang Fang, Qiuchen Pan

Translator: Audrey M. Jiang

ABSTRACT

On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law, a discriminatory law intended to prohibit Chinese immigration and the naturalization of already-existing Chinese immigrants [1]. Violators of the law were imprisoned and deported. What was unexpected, however, were the unforeseen consequences: racists capitalized on the law, resulting in a flood of violence against Chinese communities, mostly in the west (see the Rock Springs Massacre of 1885; and the Hell Canyon Massacre of 1887).

As stated above, the original intention of the policy was only to prohibit Chinese immigration, and was also intended to end after ten years. But as anti-Chinese sentiment rose and circumstances changed, however, policy also changed. By 1892, measures such as the Geary Act required all Chinese residents in the United States to carry “certificates of residence” or “dog tags,” as the Chinese community tended to call them. When the Chinese Exclusion Act entered its second decade, with the support of the Chinese government and the Six Companies (the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in San Francisco, California), many Chinese immigrants began organizing to resist the enforcement of the law. The brave efforts of average Chinese Americans turned out to be one of the largest mass civil disobedience movements in US history.

This small “golden period,” however, would not last for long: the Qing Dynasty, in its twilight years, was weak and opted to abandon overseas Chinese in exchange for an economically advantageous deal with the United States. During that time, the Six Companies also lost their most powerful ally in the struggle against the Geary Act. With no allies anywhere, Chinese Americans were left with one choice: abide or else. Even during the height of the protest, there were no laws against any random person arresting an illegal Chinese immigrant, and vigilantes targeting Chinese Americans enjoyed a free reign of terror. In 1902, the complete exclusion of Chinese immigrants became a permanent law and the legal channel for Chinese immigrants would remain shut for another 40 years. It was not until the Magnuson Act in 1943 that the doors of American immigration were finally thrown open for Chinese people.

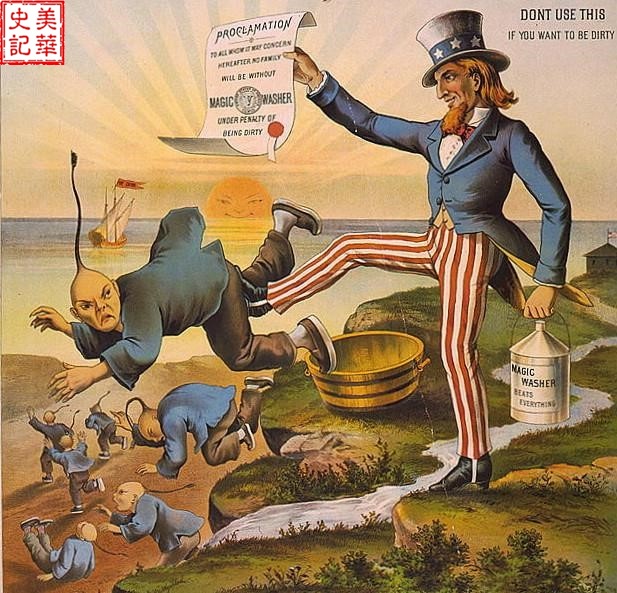

Figure 1, a nineteenth-century political cartoon depicting Uncle Sam kicking the “Chinaman” out. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Exclusion_Act#/media/File:Coolieusa.jpg

The Fight For Legal Protections After the First Decade

After the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a portion of white Americans in the Midwest launched a large-scale attack against the whole Chinese race. They were ruthless and unrelenting in their brutality, the details of which are in our previous article on the Chinese Exclusion Act. Initially, some Chinese Americans chose to arm themselves and formed self-defense groups. Soon, though, others quickly came to realize the value of fighting for their rights through litigation: it allowed for the atrocities committed to become recorded in the highest courts of law, and it also promoted lasting change– two groups of people fighting in a small area always inevitably leads to more violence. As a result, Chinese Americans picked up the weapon of law in order to fight the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act. In the first decade of the Chinese Exclusion Act alone, Chinese Americans fought more than 7000 court cases, most of which they won. [2]

At first, immigration officials and federal district courts shared the responsibility for the enforcement of the law. This arrangement continued until 1905. During that period of time, Chinese immigrants could appeal their cases to court if they were initially refused entry to the United States. The legal process for this could be quite lengthy and protracted, so it was not uncommon for American officials to fear the dogged determination of Chinese Americans, especially in their court cases. Through the use of litigation, Chinese Americans were able to carve out a space for themselves and rectify unfair laws, despite not being citizens, or having the ability to run for elected office.

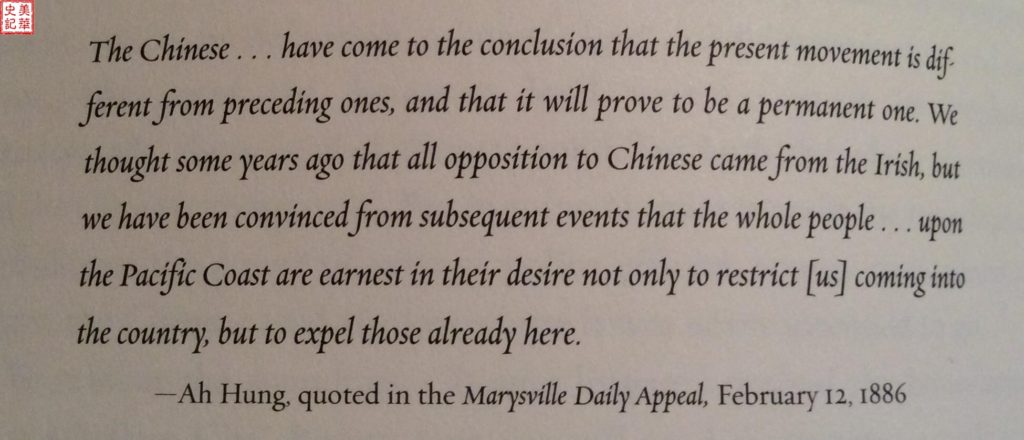

Figure 2, the Marysville Daily Appeal reported that the Chinese originally thought that the Irish were behind most of the rising anti-Chinese sentiment in America, but quickly came to the realization that nearly all white Americans wanted them gone. [2]

The ten years between 1882 and 1892 were enough to make Chinese Americans realize that the Chinese exclusion movement was not temporary and was not to be underestimated. In return, they adopted a hardened resolve to win a place in America and the respect of the people through law, despite the difficulties of playing the political game inherent to the system. That is probably the single greatest contribution the ancestors of modern-day Chinese Americans have given their descendants: The power to expand upon and explore the possibilities of the law.

Ten years later, Democratic Congressman Thomas J. Geary wrote and sponsored the “second” Chinese Exclusion Act, titled the Geary Act, which would prolong the ban on Chinese immigration another ten years. The law was controversial, prompting a series of challenges in court, but was ultimately passed on May 5, 1892. The House voted 178-43 to pass the law and the Senate 30-15 [3].

Not only did the Geary Act extend the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act’s ban on immigration, it also required “every Chinese person to register for and receive a certificate of residence, on which there was to be glued a photo showing the distinct facial features of the certificate holder, with no less than 1.5 inches between the hairline and the chin.” In addition to an identification photo, the certificate would also include the certificate holder’s name, age, place of residence, and occupation. The cost to procure such a certificate did not exceed $1 (17.58 USD in today’s money) [2].

The Geary Act also mandated that Chinese workers register for an ID card, of which one copy was supposed to be kept in an IRS office. Two white witnesses were required to verify any Chinese person’s immigrant status. Chinese Americans were also required to have their certificate of residence on them at all times. Those who refused could be punished with a year of forced labor and then a prompt deportation [3]. Furthermore, Chinese Americans were not allowed to testify in court, nor were they permitted to be released on bail in normal habeas corpus procedures.

Many Chinese Americans saw the various certificates and ID cards as degrading, and refused to carry these so-called “dog tags.” Through the collectively donated money of many Chinese Americans, they managed to hire lawyers to plead their case in the courts. The resulting legal battles persisted for another two years.

110,000 Chinese Americans Unite in Civil Disobedience

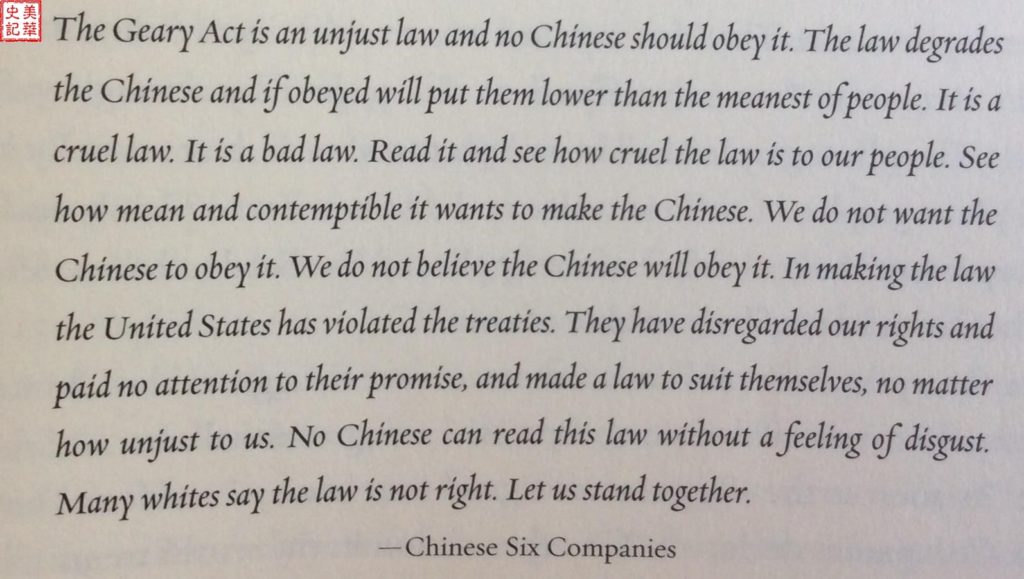

On September 19, 1892, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association called upon the 110,000 Chinese Americans across the country to rise up in large-scale protest against the Geary Act. In an act of civil disobedience, they refused to wear the “dog tags” required by the Geary Act and each pitched in one dollar toward the lawyer retainer fee. Their goal was to overturn the Geary Act on the grounds of unconstitutionality. To understand just how like-minded Chinese Americans were in their goals, Chinatown walls and windows all over the country, for a time, were covered with red leaflets about their cause[2].

Figure 3, public announcement from the Six Companies calling upon Chinese Americans to unite against the injustices of the Geary Act [2]. The Six Companies were a predecessor to the San Francisco branch of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. The Six Companies were comprised of the Sam Yup, Yeong Wo, Kong Chow, Ning Yung, Hop Wo, and Yan Wo Halls. The Sue Hing Hall, a later addition, became the seventh company.

Under the leadership of the Six Companies, regions outside of the West, such as New England, New York, and the South also joined the resistance movement. In New York and Brooklyn, the Chinese Equal Rights League called upon everyone to pitch in to help their compatriots. As part of their efforts, they recruited about 150 Chinese businessmen and professionals fluent in English to submit an appeal together, so as to strengthen their movement. The Chinese Equal Rights League also received strong support from many white Americans on the east coast. On September 22, 1892, over a thousand American citizens joined their countrymen at a rally supporting 200 Chinese businessmen and workers [4].

The Qing envoy to the United States, Tsui Kwo Yin, took his grievances right to Secretary of State Blaine on the day of the signing of the law. Other Chinese officials, such as deputy consul Ouyang Qing, took more direct action, asking the Qing government to intervene. The act was not well-received in America either: Illinois representative Robert Hitt condemned the act for “tagging” men, like “[in] the sad days of slavery…” [2]

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association was less than kind to those Chinese Americans that did not heed their call and still attempted to register for a certificate. For example, they warned and harshly condemned those Chinese businessmen that offered their services to the government during the registration process. Some restaurant and butcher shop owners registered for certificates, and were promptly taken care of by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, who would accuse them of violating sanitation regulations and dole out punishment. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association also had a deal with the Pacific Shipping Company, which required that anybody who wished to acquire a ticket to board one of their ships had to present proof that they had refused to register for a certificate of residence. The efforts of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, though, were met with equal resistance from the opposing side. California hemp mills threatened to fire employees who did not register for a certificate and assisted the IRS in setting up an office. In response, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association promptly ordered Chinese American workers to go on strike, thereby foiling the plans of the IRS. Because of this, white newspapers took to calling Chinese Americans servile and the slaves of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association [2].

In March 1893, 3 months before the deadline for registration, the San Francisco IRS office announced that they would be arresting anyone who did not register by the due date. But by April, the city government had noticeably softened its stance. They suspended the requirement that the certificate had to have a photo of the certificate holder, and decreased the number of white witnesses required from two to one. Despite this, most Chinese Americans still refused to register for a certificate.

Because they had enough organization and discipline, Chinese Americans’ defiance in the face of discriminatory laws was rewarded with huge success. Before the deadline in April of 1893, only 3169 people registered for a certificate. Even those who were forced to registrate because of circumstances deliberately omitted information and provided non-standard photos as a token of their resistance. Of the people who did register, a good portion of them were Chinese women who had registered to obtain legal protection for themselves and their children. In one case, 40 fugitive prostitutes and their five children applied for certificates of residence at a church in San Francisco [2].

As the registration deadline drew nearer, down to a matter of mere days, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association still did not falter in its campaign. They issued another announcement, calling on Chinese Americans to once again resist the act and also prohibiting Chinese Americans from complying with the act and registering for the “dog tags.”

As the situation progressed, tensions rose. Danger tends to go hand-in-hand with controversial civil disobedience movements, and this one was no exception– the lives of Chinese Americans were put at risk as a result of the exclusion movement’s power. The leader of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association personally traveled to San Francisco’s Chinatown to prevent violence, and Secretary of State Walter Q. Gresham sent an urgent message to officials and state governors all over the country to protect the lives of Chinese Americans [2].

On May 5, the registration deadline, the official counts came rolling in. In San Francisco 2000 people (out of 28000 total) registered, in San Diego only 15 registered, in Los Angeles it was 103 out of 5000, and in Chicago 945 (out of 2500) did [2].

The Bitter Struggle For Rights Enters Into a Stalemate

On the second day after the deadline, the executive judge of the federal court arrested three Chinese Americans in New York’s Chinatown. The three arrestees were selected by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. Of the three, Wong Quan and Fong Yue Ting had already lived in the United States for fifteen years. The third, a laundryman named Lee Joe, had registered for a certificate, but had not managed to get a white witness [2].

A judge of the New York district court ordered that these three be deported, on bail of $500. Two days later, San Francisco lawyer Thomas Riordan appealed this deportation order to the Supreme Court. This lawsuit originated with Chinese Americans, who wanted to try their hand at using the law to overturn the Geary Act. Their hopes would soon be quickly dashed. The Supreme Court took only about 5 days to come to the conclusion to uphold the Geary Act, 5-3. The majority opinion was written by Justice Horace Gray [5, 6]. The verdict asserted that the United States, as a sovereign nation, had the right to exclude any person or race as it saw fit. In addition, the Court also declared that local police and immigration officials could deport Chinese Americans without trial [7].

The ruling of the court caught the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association off guard, who were so confident that the high court would overturn the Geary Act. In the fallout, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association plummeted rapidly in prestige, straining the relationships between some Chinese companies. At its worst, infighting in the form of riots broke out in Chinatown [2].

Within two weeks, the Qing consulate and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association came together to launch the second round of legal battles, submitting an appeal to the New York Circuit Court. They threatened that if they were deported, they would refuse to pay the costs of returning to China, thus letting the American government incur the expenses. The Qing government also warned the Americans that if they were to take legal action, China would end all diplomatic and economic relations with the United States.

On August 11, 1893, United States District Court Judge E.R. Ross ordered the arrest of Wong Dep Ken, an unregistered Chinese American. Dep Ken was accompanied by an armed escort from Los Angeles to San Francisco, where he was forced aboard the Rio de Janeiro ship bound for Hong Kong. Dep Ken became the first Chinese American to be deported under the Geary Act [2].

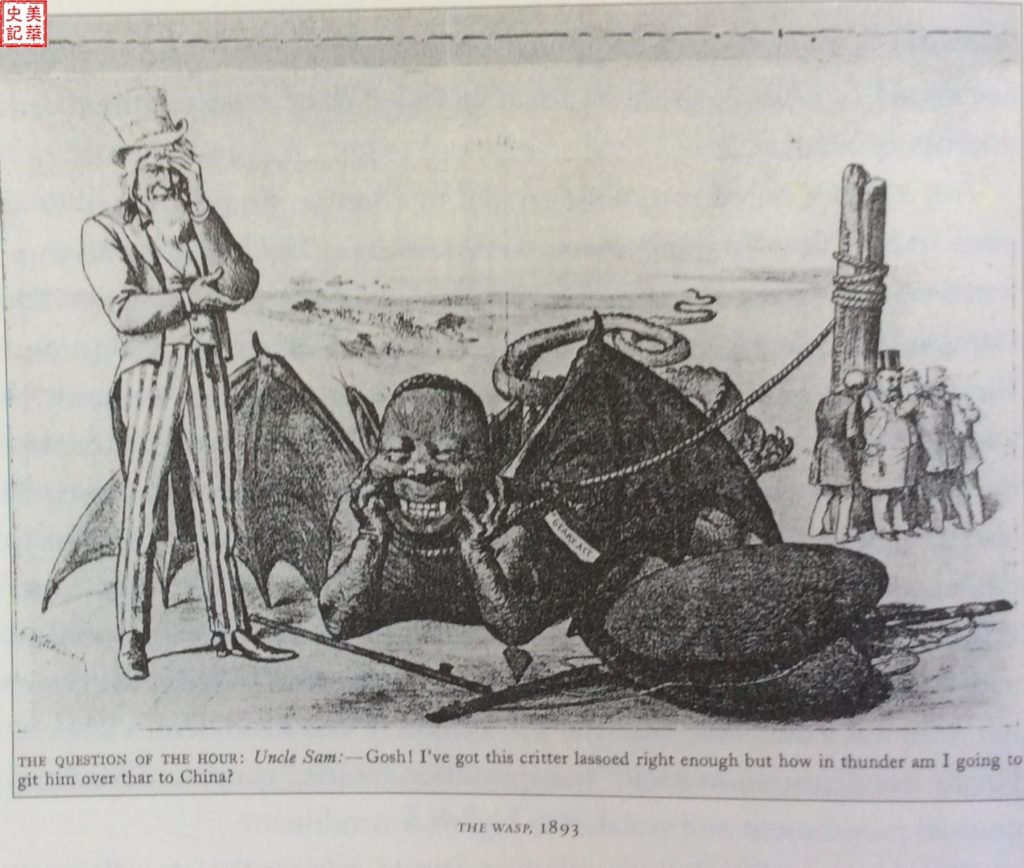

The forced repatriation of Chinese Americans put severe economic pressure on the United States– the cost of detaining and deporting Chinese Americans could easily become another 6-7 million dollars squandered, especially when Congress had only authorized $60000 for that purpose. The Geary Act had not set out a clear process for deporting Chinese Americans, which only compounded the government’s financial troubles [8]. In order to solve this problem, the McCreary Amendment was passed on November 3, 1893. The amendment provided Chinese Americans an extra six months to register (meaning the new deadline was changed to May 1894), and $100000 were allocated for the purpose of repatriation.

By March of 1894, 303 Chinese Americans had been deported, but the cost of deportation was still quite expensive– it could cost as much $1000 per person deported if they left from San Francisco or New York. As a result, the $100000 given by the McCreary Amendment was still barely enough: only $16866 was left before the May deadline. The high costs of repatriation made the implementation of the Geary Act difficult [2].

Figure 4, a political cartoon depicting the severe economic pressures that prevented the repatriation of Chinese Americans. This photo is taken from the book Driven Out [2].

On the other side of the planet, when the reports came rolling in about the violence being directed toward Chinese Americans, anti-American sentiment soared to a sudden high. Fearing retaliation, American missionaries and businessmen in China sent a telegraph to American officials, pleading with them to stop the attacks on Chinese people living in the United States. The Qing government also sent a telegram, to the U.S. Secretary of State, in which they declared that American missionaries were not welcome in China in an effort to protect Chinese Americans [2].

The Absurd Cruelties of the Chinese Exclusion Movement

1893 was the first year Chinese Americans began to show any serious resistance to the Geary Act, in opposition to the various white militias that had targeted them on many occasions. Among these white militias were some that acted in a law enforcement capacity to expel Chinese Americans, such as the People’s Party and National Trades Union.

One of these attacks occurred in the small Colorado town of Como on August 1, 1893. Chinese mine workers panning for gold were attacked by a mob, who razed their tents to the ground and set fire to their Chinatown. The mine workers themselves were forced to flee the area [2].

On the same day in Fresno, California, several textile factories and canneries were destroyed by fire. All of the Chinese Americans there were driven out. Two weeks later, on August 14, a large number of people spontaneously gathered together in an anti-Chinese rally in the downtown area. They demanded that all employers fire their Chinese workers and replace them with white workers instead. Hundreds of white homeless people moved through the streets, urging the Chinese Americans to leave. On August 15, the day right after the rally, mobs raided the vineyards, forcing Chinese workers to leave, taking their money and belongings and tearing down the huts they lived in as well. In an extraordinary show of brutality, they even beat one man to death [2].

Hundreds of Chinese workers hid in Chinatown in Montana county on August 17, in the fear that they would be attacked on the way to escape. Unfortunately, this was a common occurrence for them, and the dangers would not alleviate soon: on August 30th, supporters of the exclusion movement set off bombs in Chinese merchants’ stores, killing their customers [2].

On September 1, in the small town of Selma in the Central Valley, 40 or so members of an armed vigilante group drove out all the Chinese American residents of that town and ransacked their homes, while the police stood by and let it happen [2].

On one particular August 31 evening in southern California, 200 white Americans arrived in Chinatown, demanding that the Chinese Americans there leave within 48 hours. All of this occurred right under the nose of the city fire department. This time, the Chinese Americans fought back, arming themselves with guns. Alarmed, the governor called in the National Guard. Later, the marshal of the court ordered the arrest of unregistered Chinese Americans, despite their duty to protect them [2].

In early fall of that year, the riots and violence meandered down to the town of Redlands, whose government arrested all 170 of the town’s Chinese Americans. Only after the arrests did they turn to a judge and request 170 arrest warrants [2].

The judge in question who granted the warrants, Judge Ross, encouraged a “hands-on” approach for civilians toward the repatriation question. By his own estimate, if ordinary people were utilized to their full potential, only $50000 was enough to get the repatriation process well underway.

On August 30, 1893, a white farmer caught a Chinese worker, A Huang, out and about without an ID card. With this one act, he let open the floodgates for a surge of civilians looking to make their own unauthorized arrests. Chinese Americans quickly fled the area, but they were often pursued and intercepted by union members, who would round them up with citizen arrest warrants. Chinese Americans were also targeted by mobs, who were far more violent; the mobs shot them with guns and attacked with sticks and knives [2].

In late September hundreds of Chinese Americans made their way toward the east coast cities. Others headed to Hawaii, and yet others resettled in safer regions of northern California.

The legalization of civilian arrests ultimately led to the spread of racial discrimination at the grassroots level among civilians. It also served to agitate the Chinese exclusion movement into a frenzied high.

Giving Up the Fight

Many people in the American government and members of Congress eagerly awaited for the Qing government to assist in upholding the Geary Act. On the surface, the Qing government seemed all for the expulsion of Americans in China, even going as far as threatening to dismiss American diplomatic corps in China. Behind the facade, though, the Qing government was frantically looking for ways to compromise in order to gain economic benefits. At the time, the China-United States trade surplus was 5-to-1. If Chinese-American relations were to turn sour, the surplus would likely greatly decrease. Fearing losing their economic advantage, the Qing government struck a new trade deal with the United States (one that involved a new trade treaty), in which they promised to give up their protection of Chinese Americans in exchange for retaining their economic advantage. As a result, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association lost much of its power when its greatest ally, the Qing government, essentially abandoned them [2].

At the same time the violence was raging and the international political game was being played, another debate took center stage as well: Should we uphold the Constitution or bow down to the power of anti-Chinese sentiment? At the center of this dilemma was the debate between different interpretations of the 14th Amendment, which reads, “[No state shall] deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The United States gave up its adherence to constitutional law and the Qing government gave up its overseas compatriots in exchange for a new trade deal with the United States.

As agreed upon in the new treaty, the Chinese government conceded that Chinese American workers were, in some cases, hostile and had stirred up great disorder. They professed to no longer supporting opposition to the Geary Act as well, claiming that the United States had the right to require Chinese workers to carry identification at all times. Ambassador Yang Ru assuaged the concerns of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, reassuring them that the treaty would benefit Chinese businessmen in the United States [2].

April 3, 1894, was the final date for legal registration in the United States. As the date neared, thousands of people awaited the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association’s next order with bated breath. Were they to persist in their defiance or give in to the wishes of the government? The Association chose surrender, advising all Chinese workers to abide by the Geary Act.

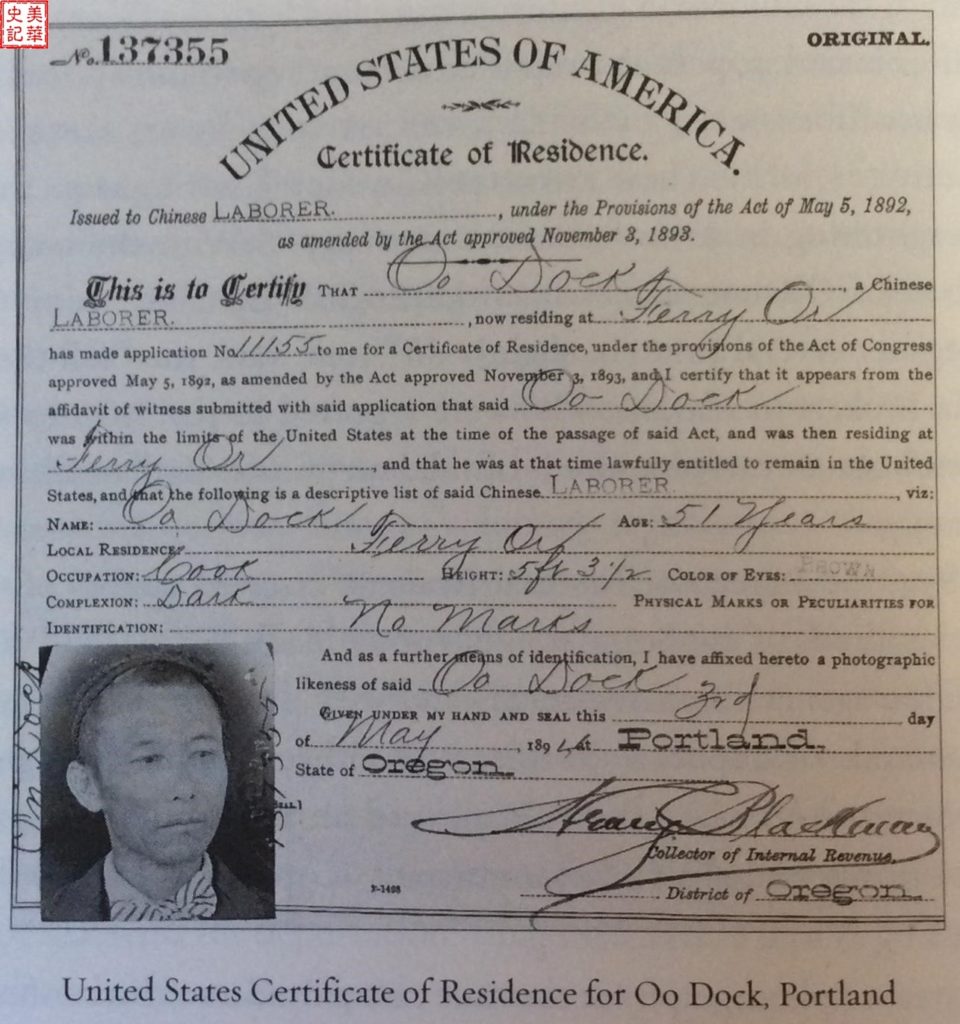

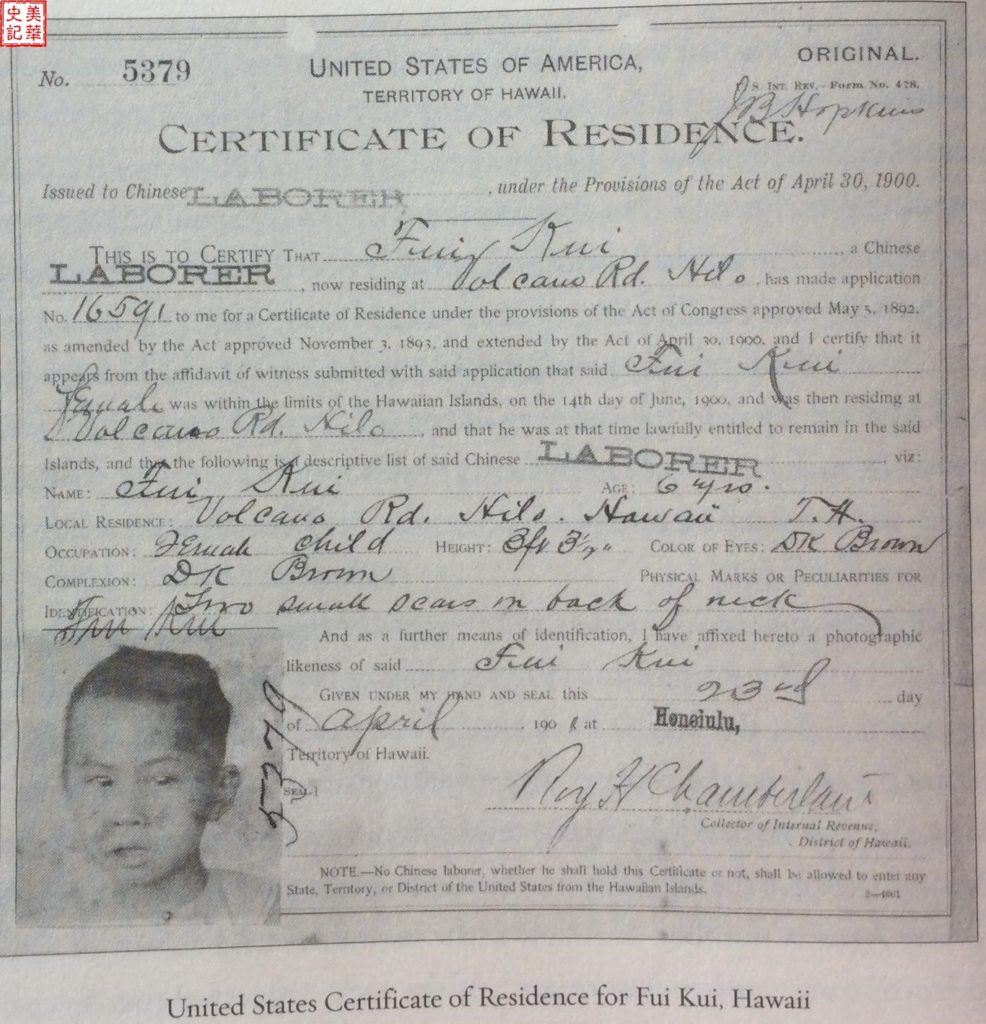

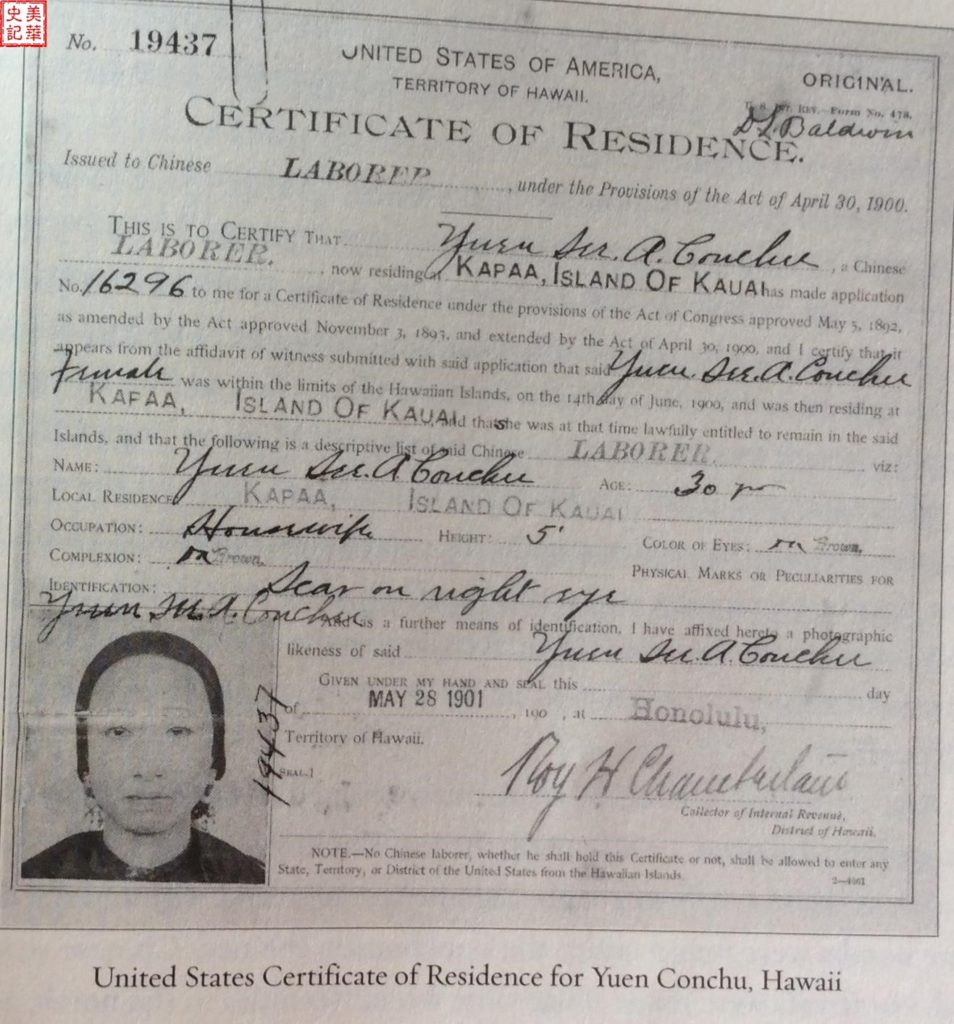

Figure 5, original copy of a certificate of residence. This photo is taken from the book Driven Out [2].

Figure 6, original copy of a certificate of residence. This photo is taken from the book Driven Out [2].

Figure 7, original copy of a certificate of residence. This photo is taken from the book Driven Out [2].

This compromise resulted in economic gain for many sides. Imports from the Qing Dynasty increased from 150000 taels of silver in 1875 to 9 million taels of silver in 1899.

In 1895 Congress appropriated $50000 to implement the new Chinese Exclusion Act, granting customs and IRS officials the final say in the immigration question. The new policy adopted by the government also greatly lessened the costs of repatriation, as officials no longer needed to hear cases before deporting someone. Before, when the costs of repatriation could exceed millions, now $50000 was more than sufficient.

Unjust laws are naturally accompanied by people looking for ways to cheat the system, and people in high places willing to help them for the right price. This case was no exception. Immigration officials, local tax officials, and agents of the Treasury accepted bribes, and the notary public office even sold blank certificates. Chinese Americans would often switch out the pinyin on the certificates and bring them back to China to sell or give away. Some people took advantage of this by volunteering for “repatriation” to visit their families, only then to return with a valid certificate of residence. In 1895 the IRS arrested dozens of Chinese Americans who were in the possession of hundreds of fake blank certificates. After this whole fiasco came to light, it was discovered that thousands of fake certificates had already been signed. The Chinese Exclusion Act brought forth a torrent of commercial smuggling, which later made its way to other nations and ethnic groups [9].

Despite evidence to the contrary, the United States proudly proclaimed the Geary Act and McCreary Amendment a resounding success. Three years after the passage of the bill, a domestic passport system was implemented. A notice was posted near Chinatown ordering all registered persons to re-register.

Of the 110000 Chinese immigrants residing in the United States from 1896 to 1905, 9571 were arrested for illegally staying in the United States, and 4000 were forcibly repatriated [2].

Emboldened by judicial rulings (which to some extent provided a legal basis for their actions), supporters of the exclusion movement intensified their attacks on Chinese Americans. By 1898, the Chinese Exclusion Act had spread to Hawaii. In 1901, 1500 representatives from labor, business, and professional organizations gathered at an anti-Chinese convention. They were highly concerned about the threat that “Mongoloid” workers posed to American labor [10].

The Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed in 1902. This time, it closed the doors to all Chinese immigration for 40 years. During this period, more and more Chinese Americans became illegal immigrants, either entering by way of Canada or Mexico, or landing on unguarded shores.

Political Lies and Rights for Chinese Americans

The Democratic Party, at the time, was eager to distance themselves from the legacy of slavery. In order to win over the votes of white Americans, they made Chinese Americans into a political target. The Republican Party, on the other hand, wished to cleanse themselves of their history of supporting African Americans and so turned their attention to demonizing Chinese Americans [11]. Similar to the beginning of the Chinese Exclusion Act, at the turning point between the first and second decades of the Chinese Exclusion Act, many white people spread political lies characterizing Chinese Americans as greedy, dirty, and dishonest.

- Some members of the labor movement even saw Chinese Americans as strikebreakers, come to sabotage their cause (mainly their strikes) [2].

- In 1877 Congress released a report claiming that Chinese Americans did not want to vote, be naturalized, learn English, or remain in the United States [2].

- In 1891, the Congressional Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship reported that Chinese Americans treated the United States as a place of temporary residence, claiming that they only planned to make enough money and then return to China to live a comfortable life [12].

Chinese Americans hailed from a monarchy that had been around for millennia, and had traveled thousands of miles to a representative democracy. The vastly different political systems, cultures, and schools of thought came as quite a shock to most Chinese Americans, who, because of their unfamiliarity, were put at a disadvantage. So when put up against European immigrants, who had the benefit of being raised in similar cultures, Chinese immigrants really could not compete. As a result, it was very easy for white Americans to justify the marginalization of Chinese Americans using the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Chinese Exclusion Act stemmed from the rising hostility of white workers competing against Chinese American workers in the labor market. One San Francisco lawyer, H.N. Clement, even claimed that white people had more of a right to this land than any “Mongoloid” groups. In his own words, white Americans had the right to say “You should never have come” to the half-civilized Asians [13]. In 1885, Stephen Field, an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, wrote to his friends. In his letter, he expressed opposition to the idea that the United States was founded for all races and asserted that it was in fact built for them, the white race [14].

Chinese American workers were often criticized for not participating in strikes, but it is important to make the distinction that they did not appear in white strikes. Chinese American workers did organize and participate in their own labor unions and strikes. For example in the 1880s, Chinese carpenters, cigar makers, laundry workers, and farmers collectively went on strike for their interests. One major strike occurred on September 10, 1893, in which Chinese workers held a general strike protesting the violence and vitriol that often ended up being directed specifically at them. The strike was major enough that laundromats and restaurants closed down, and only white workers were left [2]. Another common misconception and/or stereotype is that Chinese Americans were always industrious and docile in their protesting and work. In reality, it was not unheard of for them to arm themselves and form self-defense groups to defend themselves against the violence they faced.

The Chinese Americans who left their homelands in the pursuit of happiness embody the essential adventurous, entrepreneurial American spirit just as much as any immigrant of another ethnic group. Though it is true that some Chinese immigrants did just plan to make money and then leave, history shows that the majority of people did decide to stay for a longer period of time, and were even willing to live separated from their families during that time. Family bonds are an important part of Chinese culture, showing that these immigrants did indeed have a commitment to this country. The family-centric focus of Chinese culture also shaped the lives of Chinese American men, who were required to shoulder the duty of continuing the bloodline and supporting the family, which manifested itself in them sending money back home and making “sacrifices” in the name of family [11].

White Americans attacked Chinese Americans by pushing the narrative that they were “passersby” that would not integrate into American culture. History, however, has proven them wrong. Most Chinese immigrants never did return to their roots. It would never take anything as miniscule as a change in their residence or living conditions to make them pack up and leave, because, for them, leaving meant giving up what they depended on for survival [15].

Hear the voices of nineteenth century Chinese Americans! They have been drowned out for far too long– yet they are closer and more important to our history than we may think. Just take a look at our country’s court records, and you will see clearly illustrated their bravery and persistence in dismantling the “passersby” narrative and caricatures of Chinese people and culture. These early activists dedicated their lives and utilized the full extent of their wisdom to demonstrate how to live with dignity in a heavily anti-Chinese political environment. Their determination is why we are at where we are today. Do not silence them again.

Bibliography:

1. “The People’s Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)”. U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

2. Pfaelzer, Jean. Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans. University of California Press. 291-335.

3. Geary Act (Fifty-Second Congress. Session I. 1892) and McCreary Amendment (Fifty-Third Congress. 2d Session. House of Representatives.Report No. 457.)

4. New York Times, December 17, 1892

5. Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893). This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

6. “Fong Yue Ting v. United States”. Immigration to the United States. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

7. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fong_Yue_Ting_v._United_States

8. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geary_Act

9. Zhang, Sheldon (2007). Smuggling and trafficking in human beings: all roads lead to America. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-275-98951-4.

10.Salyer, Laws Hash at Tigers, 66

11. Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese among others: emigration in modern times. Phoenix Publishing and Media Group./他者中的华人,江苏人民出版社。19-20。

12. Report of the select committee on immigration and naturalization on Chinese Immigration, 1891.

13. Erika Lee, At America’s Gates. The University of North Carolina Press. 29, 47.

14. Stephen Field to John N. Pomeroy, April 14, 1882, Stephen Field Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

15. 黄纪凯.在地化影响下的中国海外移民行为特征探析。华侨华人历史研究。3:67-74,2017。

Pingback: White Paper: National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – 美华史记

Pingback: Promoting National Museum of AAPI – 美华史记