Author: Fan Jiao

Editors: Qiang Fang

ABSTRACT

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu (1912-1997) was an experimental physicist who is best known for her work on the Manhattan Project in WWII. She helped two colleagues win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957 based on the Wu Experiment. She was both the first Chinese American to be elected into the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and was the first female president of the American Physical Society. She was also the first living scientist to have an asteroid (2752 Wu Chien-Shiung) named after her. Her awards include the National Medal of Science by President Ford in 1975.

Her birth centenary was celebrated in her hometown of Liuhe(浏河镇), Taicang City(太仓市) in Jiangsu Province (江苏省) in 2012. Her tombstone bears the inscription “Forever Chinese/永恒的中华气质.”

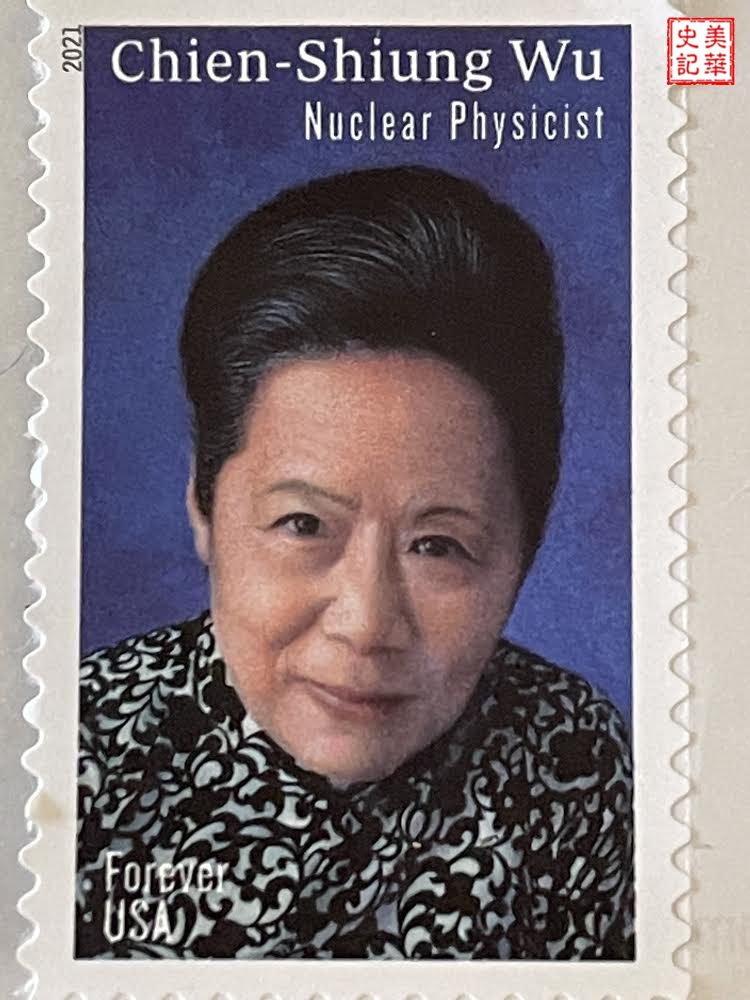

On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, February 11, 2021, the pioneering physicist’s portrait became a US Postal Service Stamp [10].

Charter School Educated Geek Girl

Source: [12]

Born in May 31, 1912 to two politically progressive and well-to-do parents in a picturesque town of Liuhe(浏河镇) near Shanghai, Chien-Shiung Wu got a rather muscaline boy name Chien-Shiung/健雄. Her mother, Fanhua Fan, was a teacher and her father, Zhong-Yi Wu/吴仲裔, was an engineer. They strongly believed in gender equality and founded one of the first girls’ schools, the Mingde School for Girls (明德女校) in Taicang together, with Wu’s father taking on the job of principal and her mother multi-tasked with persuading families in the local communities to enroll their daughters. Wu was one of their first students, and she whizzed through the elementary grades and left home at the age of 10 to continue her education at the prestigious Suzhou Girls’ High School (苏州女子高中), some 40 miles away from home.

When Wu was a high school student, she encountered a biography of Marie Curie, the great chemist and physicist who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the only woman to win it twice.

Curie’s achievements ignited a lifelong passion in a teenager who was already so devoted to science that she spent her free time teaching herself physics from textbooks borrowed from friends. But Wu probably never imagined that she would grow up to be a scientific pioneer just like her hero, or that her contributions would earn her the nickname “the Chinese Madame Curie” [3].

Elite Scientist in Making

Source: [12]

Her grades in high school were so impressive that she was immediately offered a place at the National Central University (國立中央大學) in Nanjing(南京市) , majoring in Physics, after the requirement of passing annually national-wide college entrance examination was waived.

By the time she graduated with top marks in 1934, her subject of Physics had become one of the liveliest and most exciting disciplines in the world: breakthroughs like Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity had revolutionized the field and each year promised ever more astounding discoveries. But China then had no advanced graduate program for aspiring and talented physicists that forced Wu to pursue her dream elsewhere.

On one day of August 1936, she waved goodbye to her family and friends from the deck of the ocean liner President Hoover to San Francisco. It would be the last time she ever saw her mother and father again.

After transferring from the University of Michigan to the University of California, Berkeley, Wu immersed herself in her graduate degree, only to receive news a year later that Japan had invaded China. She hadn’t heard from her parents for eight years and the conflict between the two nations would later become part of WWII after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

She met and married a fellow physicist, Luke Chia-Liu Yuan (袁家骝) at Berkeley in 1942, who was also the grandson of Yuan Shikai (袁世凱), the first de jure President of the Republic of China and a short-time emperor from 1912-1916. Because of the outbreak of the War in the Pacific, neither of their families attended their wedding. Wu did not take her husband’s name in marriage and would correct students who mistakenly called her Professor Yuan [2].

Manhattan Project

Wu was extremely worried about her family, but work provided a much-needed distraction. She carved out a reputation as a meticulous and dogged experimental physicist of the highest caliber. When future Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi had trouble with his experiments, he was told to call on Wu.

Among physicists who knew her, a saying went: “If the experiment was done by Wu, it must be correct.” In his autobiography, her mentor Emilio Segrè recalled: “Wu’s will power and devotion to work are reminiscent of Marie Curie, but she is more worldly, elegant, and witty.[0]”

Source: [6]

In March 1944, Wu was invited by her former professor, Robert Oppenheimer, to work at Columbia University to join the top-secret Manhattan Project that was a government-funded initiative to research and develop powerful atomic weapons. The project enlisted scientists of many fields working independently and collaboratively in labs across the United States. Most of them had no direct connections to warfare technology or weapon development. Rather, their individual work was necessary small pieces of a bigger puzzle. Wu’s research focused on identifying a process to separate uranium metal through gaseous infusion, which was critical to transforming a dumb bomb into an atomic bomb. She was the only Chinese descendant to work in the war department and one of the few women among its senior researchers.

In 1945, she saw the culmination of her efforts with the development of the first atomic bomb. Though she later expressed regret over its use on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the work that she had done might bring an earlier end to WWII and allowed her to finally receive word that her family was safe.

She expressed the hope that the devastating bomb was a one-off: “Do you think that people are so stupid and self-destructive? No. I have confidence in humankind. I believe we will one day live together peacefully.[13]”

Recipients of the 1946 “Young Women of the Year” Mademoiselle Merit awards include (from left) Pauli Murray, a New York lawyer; Dorothy V. Wheeler, director of nursing service, American Veterans Administration; actress Judy Holliday; and Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu of the Manhattan Project. Presenting the awards is Betsy Talbot Blackwell, editor of Mademoiselle, right. Dec. 30, 1946. ((AP Photo/John Lent)

Source: [1]

When the war ended, Wu stayed on at Columbia University to teach and continue her research into beta decay, a radioactive process in which the nucleus of an atom emits beta particles, forcing the atom to change into a new element.

Wu Experiment

Source: [4]

Nobody actually knew how beta decay worked and Wu was on the cutting edge of this new science. Her expertise brought her to the attention of Tsung-Dao Lee (李政道) and Chen-Ning Yang (杨振宁), two Chinese scientists who were investigating a law in physics known as the conservation of parity. It was believed that fundamental symmetry governed everything in nature, including the behavior of atomic particles. But Lee and Yang theorized that parity might not exist with beta decay; they just needed someone to prove it. They talked to Wu.

Wu devised a series of experiments that later proved this so-called fundamental law of science wrong using super-cooled radioactive cobalt. If the law of parity were true, the cobalt nuclei would have broken down and thrown the same number of electrons in symmetrical directions. After months of operating on only a few hours of sleep a night – she even cancelled a long-awaited return visit to China – Wu was able to prove that this wasn’t the case.

Specifically, she used decay of cobalt-60 atoms that were cooled to near-absolute zero temperatures and aligned in a uniform magnetic field. Cobalt-60 nuclei have intrinsic angular momentum, the quantum equivalent of angular momentum, kind of like a little spinning gyroscope, except it’s more a property of the particle, rather than an actual spin. Cobalt-60 decays by beta decay to nickel-60 with emission of an electron, an electron antineutrino, and two gamma photons in the overall reaction. The gamma emissions, which were known to respect β-conservation, served as a control for the experiment. Wu compared the distribution of the gamma and beta emissions with the nuclear spins in opposite orientations. The idea was to use the magnetic fields to orient the nuclei so that all the spins were in the same direction, and then count how many electrons were emitted up and down as the nuclei decayed. If parity was conserved, there should be equal numbers of each [9].

Source: [5]

The explosive news landed Wu on the cover of the New York Times. “We learn one lesson,” she later said, “never accept any ‘self-evident’ principle.”

Lee and Yang were later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1954, but Wu’s efforts in proving their theory right went unacknowledged.

Wu was aware of gender-based injustice and at an MIT symposium in October of 1964, she stated “I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.”

“Although I did not do research just for the prize, it still hurts me a lot that my work was overlooked for certain reasons,” she wrote to Jack Steinberger, a fellow physicist who steadfastly maintained that Wu should have shared in the Nobel triumph.

Source: [12]

Later Life and Legacy

Wu continued making significant contributions throughout her life and won several awards and honors. In 1958, her research helped answer important biological questions about blood and sickle cell anemia.

She was decorated with honors in every other way, including the National Medal of Science and the Wolf Prize in Physics in Israel hosted by then Prime Minister Begin (the latter is considered the second most prestigious award in the sciences, after the Nobel Prize). She even had an asteroid named after her in 1990. But as she told a biographer, the glory of scientific discovery was its own award.

“These are moments of exaltation and ecstasy,” she said of her findings about parity. “A glimpse of this wonder can be the reward of a lifetime.”

After being promoted to Associate (1952), then to Full Professor (1958) and becoming the first woman to hold a tenured faculty position in the physics department at Columbia, she was appointed the first Michael I. Pupin Professor of Physics in 1973. Wu retired from Columbia in 1981 and devoted her time to educational programs in the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, and the United States. She was a huge advocate for promoting girls in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) and lectured widely to support this cause becoming a role model for young women scientists everywhere.

Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu died from complications of a stroke on February 16, 1997 in New York City at the age of 84. Her cremated remains were buried on the grounds of Mingde Senior High School (a successor of Mingde Women’s Vocational Continuing School). On June 1, 2002, a bronze statue of Wu was placed in the courtyard of Mingde High to commemorate her life [0].

Devoted to science, she had mentored and encouraged not only her son, but dozens of graduate students throughout her career. She is remembered as a trailblazer in the scientific community and an inspirational role model. Her granddaughter, Jada Wu Hanjie, remarked “I was young when I saw my grandmother, but her modesty, rigorousness and beauty were rooted in my mind. My grandmother had emphasized much enthusiasm for national scientific development and education, which I really admire.[14]”

Source: [12]

Forever Chinese

Since her arrival in the US in 1936, American immigration laws and the Chinese political upheaval had made it further difficult for Wu to remain connected to her homeland. She was unable to travel home and communicated with her family through letters. Travel in general was made difficult by her Chinese passport. In 1954, she decided to make her Chinese American status official by becoming a US citizen.

At her home in New York City, she often recalled her early days in Taicang. Her nephew, who also lived in the US, recalled that her favorite dishes were braised pork balls in soy sauce and sauteed broad beans, among many local favorites. She liked to reminisce about her father and her childhood in China.

Wu frequently wore Cheongsam (qipao, 旗袍) and she kept an extensive collection of Chinese classic literature in her apartment at Columbia University where she lived for more than three decades.

In 1973, a year after Nixon’s ice-breaking trip to China, Wu was then 61 years old. She put on her qipao and paid her first visit to China, which she had left 37 years earlier. She visited Mingde Women’s Vocational School and her hometown.

She and her husband had made more than 10 trips to China since then. She set up scholarships in Taicang, sponsored a primary school and invited the world’s leading physicists to lecture at Nanjing and Southeast universities, formerly the National Central University, her alma mater.

For Wu’s granddaughter, a reporter at The Washington Post who’s been promoting the stamp on her social media accounts, highlighting her grandmother’s immigrant experience is an important part of the story.

“When my grandma immigrated, she was on a boat from China. For people of her generation, they got out just before the [Second] Sino-Japanese War, and then more wars (Chinese Civil War, 1946-1949), and then Maoism. She never saw her parents alive after she left. Their tombs were desecrated when she went back,”Jada Yuan says. “There was a very small community of Chinese intellectual expats who became really close, and sort of shared that experience of being separated from their homeland.”

Wu’s son, Vincent Yuan, a nuclear scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory says his mother kept a book close at hand throughout her career: “From Immigrant to Inventor.” In the Pulitzer-winning autobiography, Serbian-American physicist Michael Pupin detailed how he came to the United States with 5 cents in his pocket and just one set of clothes.

“She identified with him,” Vincent Yuan says, “in the sense that she was an immigrant, too, and came over without a whole lot of wealth. And he also was concerned about a lot of things she was concerned about science education.”

Monument to Wu at the Ming De Middle School campus in Liuhe Source: [0]

Rewards

Member of the National Academy of Sciences (elected 1958)

Research Corporation Award 1958

Achievement Award, American Association of University Women 1960

John Price Wetherill Medal, The Franklin Institute, 1962

Comstock Prize in Physics, National Academy of Sciences 1964

Chi-Tsin Achievement Award, Chi-Tsin Culture Foundation, Taiwan 1965

Scientist of the Year Award, Industrial Research Magazine 1974

Tom W. Bonner Prize, American Physical Society 1975

National Medal of Science (U.S.) 1975

Wolf Prize in Physics, Israel 1978

Honorary Fellow Royal Society of Edinburgh

Fellow American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Fellow American Association for the Advancement of Science

Fellow American Physical Society

Memorable Moments

Source: [12]

Chien-Shiung Wu with granddaughter Jada Wu Hanjie (center) and the rest of the family Source: [0]

Source: [12]

Source: [12]

References

[1] Chien-Shiung Wu: Forgotten Woman of the Manhattan Project | Time

[2] Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu, The First Lady of Physics (US National Park Service)

[3] Five Fast Facts about Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu

[4] Phenomenal Physicist: A Portrait of Chien-Shiung Wu — Google Arts & Culture

[5] Madame Wu and the backward universe

[6] Chien-Shiung Wu | Atomic Heritage Foundation

[7] Chien-Shiung Wu | Chinese-American physicist

[8] New postage stamp: Chien-Shiung Wu

[9] Wu experiment

[10] New USPS Stamp Celebrates Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, The ‘First Lady’ Of Physics

[11] Life Story: Chien-Shiung Wu, 1912-1997 – Women & the American Story

[13] Chiang, Tsai-Chien (2014). Madame Chien-Shiung Wu: The First Lady of Physics Research. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4374-84-2.

[14] Dr. Chien-Shiung Wu – The Cardinal

Pingback: Promoting National Museum of AAPI – 美华史记