Author: Zhida Song-James

Translated by: Pingbo Zhou, Zhida Song-James

I first saw Polly Creek on a map while investigating the watershed boundaries of the Salmon River. The creek runs through the jagged mountains of Central Idaho and descends more than 2,000 feet before emptying into the winding, snakelike Salmon River. Salmon Canyon’s harsh terrain makes the river drop so steeply that boats are only able to sail downstream with the current, thus giving it a reputation as a “River of No Return”. To this day, there are no roads that reach Polly Creek. Why would this faraway, remote creek have such a beautiful feminine name?

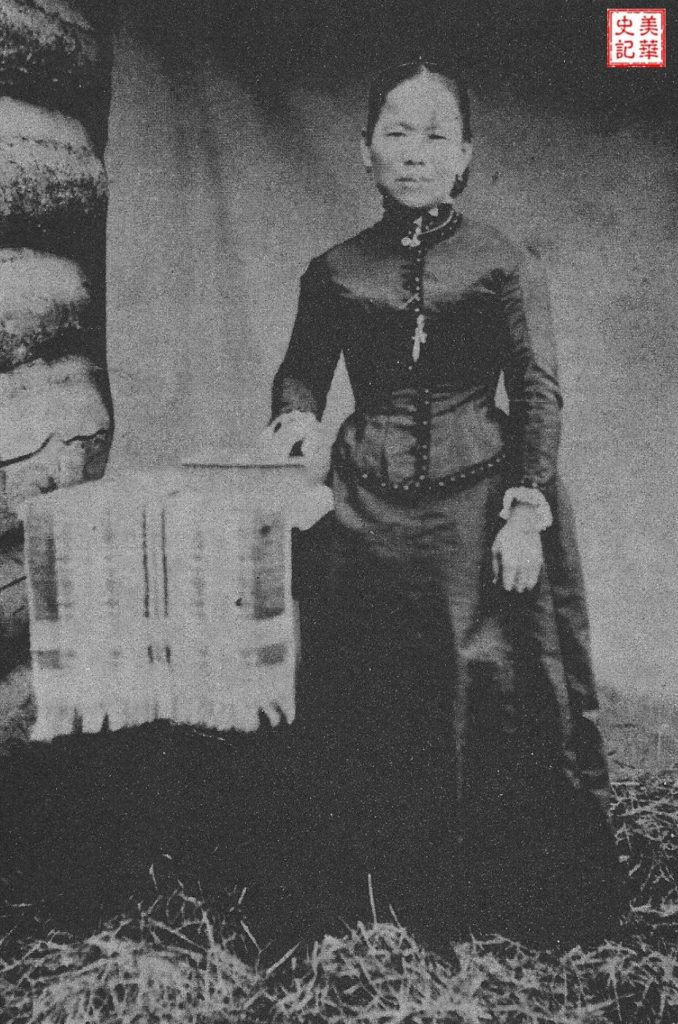

This creek was named after Polly Bemis, a pioneer woman. Upon hearing this name for the first time, I did not think she was a Chinese woman. What was her story? Out of the countless rivers, streams, and creeks in America, why was this one named after a Chinese woman?

In 1921, a female journalist named Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson (she also went by Countess Eleanor Gizycka) took a boat trip downstream along the Salmon River. After enduring a few days of harsh sun and meager meals on the river, she was surprised and delighted to discover a small farm on the riverbank. Even more shocking was that the owner of the farm, Polly, was a woman from China. Patterson was the first person who interviewed Polly and spread her story to the outside world [1].

In 1979, a book about Polly was published. The book was authored by a renowned Idahoan historian, Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn, and it described Polly’s experiences living in Idaho [2].

Ruthanne Lum McCunn, a writer of Chinese heritage, was inspired by this book. She came to Salmon Canyon, visited the mining town of Warren, where Polly had lived, as well as Polly’s home by the Salmon River. McCunn interviewed locals who had interacted with Polly and their descendants and later wrote a biographical novel titled “Thousand Pieces of Gold” [3]. This book was later translated into six languages, including Chinese, and was adapted into a movie of the same name. This allowed Polly’s story to reach an even wider audience.

All of this contributed to Polly becoming the most well-known Chinese woman in Idaho, if not the entire Pacific Northwest. Her story has appeared in publications, movies, children’s books, and educational materials [4], yet to this day no one knows for sure what her Chinese name was or where she was born. There is even uncertainty surrounding what year she was born with 1849 and 1853 in different records [5]. Most of the information we have is based on interviews and recollections from her and her friends, and there are often contradictions in the details. This article is based on the historical record and is intended to introduce her legendary experiences, diligence, kindness, positivity, and tenacity, and does not seek to serve as a deep dive into any particular details.

Coming to a Mining Town

Polly was born to a farming family in north China, the exact location remains unclear. All that is known is that it was upstream of a river and that living conditions were harsh, with frequent attacks from bandits. The record shows that her birth name was phonetically translated to “Lalu Nathoy” [6] [7]. A long-lasting drought caused her family to fall into poverty. In order to save their family, her father was forced to sell her in exchange for seeds for the next season. There are no specific historical records of her life in China, and she provided varying answers across numerous interviews when asked how she arrived in America. She mentioned something about Shanghai, and also that after arriving in America she was resold for $2,500 by an old woman. She also said she took a boat up the Columbia River from Portland, Oregon, before finally arriving alongside a caravan to the Idaho mining town of Warrens (now named Warren) in 1872. She was bought by a saloon owner named Hong King. The locals called her Polly. Saloons in western towns often served multiple purposes: bar, casino, brothel, entertainment center, and occasionally a gathering place for gunslingers. Polly was short of stature, with delicate features, and could very likely have been purchased as a prostitute; however, the vast majority of those later interviewed about her life stated that she had never worked as a prostitute and instead was taken in by the saloon owner himself. Even those who believed she had worked in the oldest profession spoke of her in tones of great respect. At the saloon, she worked as a waiter and hostess, and occasionally played cards or danced with the customers. In Warren, there were some Chinese miners who spoke Cantonese. However, since Polly came from north China and did not speak the same dialect, she was unable to communicate with other Chinese and did not interact with them much. It was around this time that she met the owner of the other saloon, Charlie Bemis.

Picture 1: Polly sitting in front of her home. Picture taken from [6].

Charles Bemis was originally a Connecticut craftsman who made jewelry for a living. He came to Warren along with his father Alfred during the Gold Rush. His father struck it rich and owned some of the most valuable properties in Warren. Charlie liked music and knew how to play the violin, but did not have the strong physical build required to be a good miner. He was also a bit lazy and not interested in manual labor. Between 1870 and 1880, he opened a saloon to make a living. Charlie had a reputation as a skilled but honest gambler. In addition, his bravery, skills with a gun, and status as a white man enabled him to control drunkards looking for a fight in the saloon. It was love at first sight for him when he saw Polly – when she was harassed by drunkards at her saloon, Charlie often stepped up to protect her, and she often directly escaped to Charlie’s to hide[8]. There is a widespread theory that Polly was a poker bride: Charlie staked his home and wealth against Hong King’s Polly and gold. In the end, it was Charlie who emerged victorious, winning Polly and giving her freedom. This story is not supported by any substantial evidence [9], but what we know is that by 1880 Polly had left Hong King’s saloon to live with Charlie. According to 1880 census records, Polly’s profession was a housekeeper, and her marital status was widowed [10]. This indicates that she identified as Hong King’s concubine, but did not work as a prostitute.

Picture 2: Charles Bemis, sourced via [26]; public domain.

In Western mining towns, a female housekeeper’s job often entailed managing a boarding house that provided food and lodging. Polly was economically independent and operated the boarding house and laundry on her own. No one taught Polly how to cook; she simply learned via watching others. She recalled that there was once a guest who complained about the taste of her coffee. The next morning, she entered the dining room with a kitchen knife and asked, “Who said my coffee tasted bad?” Polly’s boarding house did not solely provide lodging to miners. Government workers, such as surveyors and postmen would often stay there, and many of them went on to become her friends. Polly was friendly with other women in the town. Bortha Long was one of her best friends. Even the thick snowdrifts of winter could not prevent them from visiting with each other.

In May of 1887, Charlie’s home caught fire and was nearly burned to the ground. By September, he had built a new house. In 1889, Charlie became the local deputy sheriff but was involved in a gambling-induced gunfight in September of that year. The bullet hit him in the face and shattered his cheekbone. The closest physician to Warren, Dr, Bibby, lived more than ten miles away in Grangeville. By the time he arrived on horseback, Charlie had nearly perished. The doctor tried his best to remove half the bullet and multiple shattered pieces of bone, carefully extracting them from the wounds. He stopped because he thought that Charlie was too weak to endure further surgery in his state, and was worried that the blood poisoning induced by the bullet could further threaten Charlie’s life. However, Polly refused to give up. After the doctor left, she used her crochet hook to continue cleaning Charlie’s wounds, washing them up, and applying herbs. The results were nothing short of miraculous. After several weeks, Charlie was able to sit up and dress himself. Polly continued patiently taking care of him, and finally found the last piece of the bullet lodged in the back of his neck, which she removed after cutting open the wounds with a razor [11].

In that same year, the other Chinese woman living in Warren passed away. Polly did not see another Chinese woman until she went sightseeing in Boise in 1924.

The U.S. vs. Polly Bemis

The Geary Act of 1892 required all legal immigrants from China to carry government-issued identification at all times and deported those who violated these requirements. Charlie and Polly both knew that Polly had been smuggled into the U.S. Although they had already lived together for many years, they both thought that marriage was the only way for her to establish legal residency. On August 13, 1894, the two filed their registration of marriage in Warren. Polly’s name was entered as Polly Nathoy on the marriage certificate. Like many other western states, Idaho prohibited intermarriage between whites and people of other races. However, the laws that were enforced at the time in 1894 did not include Chinese people among the list of races with which whites were not allowed to intermarry – A.D. Smead, the white judge who presided over their wedding, had himself married a Native American woman. When the state laws were changed in 1921 to include “Mongoloids” in the list of races prohibited from marrying with whites [14], Polly had already lived along the Salmon River for over 20 years as “Mrs. Bemis”, and no one took issue with them over this.

Picture 3: Polly’s wedding photo in 1894. This photo was later used for her ID as well. Sourced via [26]; public domain.

In May of 1896, Polly was among 50 Chinese living in Idaho who were arrested because they did not have proof of legal residency. The case of U.S. vs. Polly Bemis was presided over by the District Judge of the Circuit Court of Idaho, D.A. Hall. The 50 Chinese all hired the same lawyer, D. Worth. Worth argued by presenting the facts. In the winter of 1895, heavy snowfall blocked the roads connecting the mining towns deep in the mountains to the outside world. When spring came, melting snow and rain damaged the road that the officials responsible for issuing the documents would have traveled by, rendering them unable to travel to the mining towns. As a result, these Chinese were unable to register for legal residency, had done nothing wrong, and should not be criminally prosecuted. The law at the time required that a white person must testify on Polly’s behalf. Her witness said that Polly was a peaceful, law-abiding “Chinaman” who had been in the laundry business in Idaho for over ten years and had never broken the law. The judge accepted the testimony and ruled that all of the Chinese were not guilty [15]. Following the ruling, the government issued them all proof of legal residency. Polly’s documents stated that she was 47 years old in 1896.

Picture 4: Polly’s court records in 1896. Sourced via [15].

Polly’s Farm on the Salmon River

After getting married, the Bemises purchased a mining claim outside the town of Warren and fenced off a two-acre area on the southern banks of the Salmon River, 17 miles outside of Warren. There, they built a two-story house and settled down. Idaho law permitted Chinese people to own mining claims but not property; the Bemis’ mining claim ensured that Polly could maintain her legal resident status and remain in Idaho. Every spring, Charlie and Polly would go do a little workaround for their mining claim to meet the requirements for maintaining the claim. Diligent and hardworking Polly planted an orchard on the hillside. She grew pears, cherries, plums, and chestnuts, as well as grapes, watermelons, raspberries, and blackberries. She raised cows, horses, chickens, and ducks. She nurtured a family of robins and even once took care of an orphaned baby mountain lion. She cleared away shrubbery around the house and started a giant garden, planting vegetables, squash, tomatoes, corn, and even medicinal herbs. Charlie played an atypical role in this household – while Polly worked in the garden, planting and weeding, Charlie would play his violin for her and their crops. He would beckon her to look at the ants, and she would tell him to learn from their diligence and take the firewood into the house.

Charlie’s main duties were going into Warren to sell their farm’s produce, taking care of business at the saloon, and occasionally being invited to play music at dances. Polly enjoyed life by the river and was an adept fisherwoman. At three P.M. each afternoon, she would go fish by the river. She often accompanied Charlie on hunting expeditions as well. Polly had a good eye and was responsible for spotting prey; Charlie was the better shot and took care of shooting. The Bemises loved company and often invited friends from town to visit when the weather permitted, often playing card games. Polly always made sure her friends went back with plenty of vegetables, fruits, and snacks from her garden and kitchen. Charlie would also often take people across the river for free on his boat. Eventually, their farm site became a popular ferry as well as a stop for those who came down the river. Captains would bring tourists from upriver to their home to relax and enjoy both the fresh fruits and vegetables they did not have on the boat and Polly’s warm hospitality and sharp wit. Those who fell ill on the journey would receive special care from Polly as well. The Bemis Ranch quickly became “Polly’s place” among the travelers on the river. In 1911, the government sent surveyors to map out the region. The creek that crossed the Bemis Ranch was henceforth officially given its beautiful name, Polly Creek [16].

Picture 5: Horses were Polly and Charlie’s main form of transport when leaving the home. Sourced via [26], public domain.

In 1904, a fire engulfed Warren’s main street and burned down Charlie’s house and saloon. After that, he rarely came to town and chose to continue his peaceful life by the river. He and Polly were not completely alone – the Smith-Williams farm was just across the river. Charles Shepp, a German immigrant who owned a nearby mining claim, often went to their farm to buy produce and soon met the Bemises. In 1909, Shepp and his young friend Pete Klinkhamer bought the Smith-Williams farm, and soon became close neighbors with Charlie and Polly. The two men would come to Polly’s to buy vegetables and eggs, and Polly would invite them to spend Thanksgiving together, making sure they left with her biscuits, cookies, and pickled vegetables. Shepp was a skilled carpenter and often helped Polly with woodwork around the house. Importantly, there was a better road on the north of the river. Each year before winter came, Shepp and Klinkhamer would help Polly store away enough flour, coffee, and other winter essentials. Pete would travel by horseback to Grangeville to buy the supplies and bring them back to the river, a six-day round trip that took him across tough mountain terrain. Eventually, Shepp erected a phone line that crossed the river, allowing the friends on opposite riverbanks to chat each day. Soon the phone lines extended out of the mountains and into town. From then on, even if snow blanketed the mountains, the residents did not have to feel cut off from the rest of the world. The neighbors would often gather together to listen to the radio, listening to everything from the weather to music to talk shows, as well as keeping up with what was going on in the rest of the world.

Charlie was never a physically strong man. In 1921 when the aforementioned Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson came to Polly’s farmstead, Charlie had become bedridden with tuberculosis. There are many entries in Shepp’s diary about how they would cross the river to help Polly sow the field, clear brush, and mow down the grass, among other duties. In August of 1922, Polly’s house caught fire. Polly risked her life and was able to pull Charlie out of the house with Shepp’s help. By the time Pete got there, everything was gone. All that he could save was a flock of chickens. After that, Charlie and Polly stayed at Shepp’s farm for two months, until Charlie passed away on October 29th. Shepp and his friend laid Charlie to rest on his farm. Charlie’s grave sat north and faced south, with the river in front and the hillside behind. It remains there to this day [17].

Out of the Mountains and Into the World

Charlie’s death hurt Polly deeply. They had known each other for nearly fifty years and had lived together by the river in relative solitude for more than twenty years. Now everything was gone, and the nearly seventy-year-old Polly was all that was left behind. Shepp and Pete, both bachelors, could no longer keep Polly with them on their farm. At that time, there were still Chinese people living in Warren along with Charlie’s old friends. The two men thought that sending her to Warren was the best solution. They put all of Polly’s possessions on horseback, along with potatoes, squashes, and other foods, and Pete accompanied her to Warren and helped her settle down in a small house. Polly had no kids of her own but loved children, and children got along with her easily as well. The population in the area was sparse and widely dispersed; families who lived out of town had to send their children to Warren to attend school and have them live with friends or relatives in town. Polly hosted one such child, Gay Carrey. Gay’s home was on the south fork of the Salmon River. Her older brother Johnny would stay in an inn when he came for school, and Gay would stay with Polly. Polly took care of her everyday needs, Carrey’s parents would provide her with essentials, and her brother Johnny would often come to help Polly around the house. Shepp did not forget about Polly either – although he knew she was illiterate, he would often write letters updating her on how things were going by the river. He knew Polly would be able to find someone to read it to her.

The following summer, Sheep’s younger brother and sister came to visit him and also visited Polly in town on their way out. With them, Polly took her first ride in an automobile to Grangeville, where she stayed with an old friend. It was there that the Idaho County Free Press interviewed her. She recalled that when Warren opened a school, she could not go to school but had to work to earn a living. She pointed at her head and said, “God gave me a brain, I have been learning ever since.” People flocked to come to see this short, gray-haired old lady who weighed less than 100 pounds and was clad in simple garments. Polly made full use of the conveniences of city life: she got glasses, visited the dentist, and even went to go look at trains with her friends. When the locomotive engineer heard it was her first time seeing a train, he let her into the engine room to see the raging flames in the boiler and explained to her how the train was able to move. In the city, Polly watched a movie for the first time ever as well. She was very happy and said that these were some of her happiest days in over 50 years and that she might come back next year. In the summer of 1924, Polly ventured out for the second time. This time it was a former guest of her boarding house from 32 years ago, Jay Czizek, and his wife, who brought her to the state capitol of Boise to sightsee. They stayed at the Idanha Hotel. Here, she saw multi-story buildings for the first time, took her first ride on an elevator and in a streetcar, and watched a movie for the second time. Polly was now practically a celebrity. She was followed by even more reporters and conducted even more interviews. She said that Charlie once had said they would never see the railroad in their lifetime, but she had already seen a train last year. Now that she was in Boise, she had seen buildings that were five or six stories tall, streetcars sharing the road with pedestrians, and more people and excitement than she had ever known. She said these things were good, but she could not take too much of them. With regard to her opinion on fashion trends in the city, she said the clothing was fine, but she had no interest in curling her hair [18].

Returning to the Salmon River

Polly’s heart remained with the Salmon River which she took as her true home. One early fall morning, Shepp noticed smoke coming up from the opposite bank and hurried over with Pete, only to find that Polly had returned. She had walked 17 miles to return to her home by the river which only had chicken coops remaining. She proposed a plan that the two men help her rebuild her home and take care of her for the rest of her days. In exchange, she would gift her house and farm to them. The men agreed and quickly got to work. The house was built at the original site and was completed in early October 1924. Shepp went to Warren to pick Polly up to see her new home. Afterward, Shepp continued to build a fireplace, make furniture, and reconnect the phone lines, while Pete stored enough firewood for her to get through the winter. Polly moved in before winter came. Shepp and Pete continued improving Polly’s home; they installed floors, fixed windows, built a fence, and continued doing the heavy lifting around the house.

Under the Alien Land Law at the time, Polly could inherit Charlie’s estate as his widow, but she and other Chinese immigrants were restricted from owning residential property. As a result, she could not keep the homestead that she and her husband had built from the ground up [19]. In such a helpless situation, perhaps transferring the property ownership to those she trusted was the smartest decision and the best solution. Polly continued planting and cultivating her garden and would venture out on horseback or foot in her spare time. She sold produce to the miners who lived nearly and often gave them whatever excess she had for free. Those who saw her said that her mind remained sharp and that she was still energetic in her old age.

Picture 6: Polly’s home. Photographed by Priscilla Wegars, sourced via [27]. Thank you to the author for providing this image for public use.

Polly and her neighbors on the opposite river maintained their habit of chatting on the phone each day. As Polly got older, Shepp and Pete made a point of asking Polly how her day was every day and saw it as a way to look out for her. On August 6, 1933, Polly did not pick up the phone. Shepp and Pete crossed the river to check up on her and found her laying on the floor unconscious. The hospital was in Grangeville, quite far from their location. They phoned for help, and immediately put Polly on a horse, taking her along winding mountain roads towards Grangeville. The nurses and ambulance that were sent to meet them could only reach the abandoned War Eagle Mine. Shepp and Pete brought her to the mine, where she was transported the rest of the way to the hospital by the ambulance. The entire arduous trip took nine hours. Polly’s will to live was extremely strong. At the hospital, even though she could not get out of bed, her eyes would spark excitedly whenever she heard children’s voices. The people knew that she did not have much time left and all came to visit her and say their goodbyes. Among them was her life-long friend Bortha Long, who brought her grandson with her, as well as Frank McGrane, who had his meal in her boarding house only once a decades ago. The elementary school teacher brought her entire class of students to give Polly a chance to smile again and to let the children pay their respects to this legendary woman.

On November 6, 1933, Polly passed away in Grangeville at the age of eighty. She once said that she wanted to be buried at Salmon Canyon, next to Charlie. However, it was already deep winter in the mountains by November and conditions were harsh. Shepp and Pete were unable to make it in time. At the funeral, the members of Grangeville’s city council served as pallbearers, and she was buried at Prairie View Cemetery.

Before his death in 1936, Charles Shepp left his half of Polly’s farm to Pete in his will. In the same year, Pete completed the registration of Polly’s farm. As a devout Catholic, Pete donated Polly’s possessions to St. Gertrude’s Museum and told Polly’s life story in detail to Sister Mary Alfreda Elsensohn, the Museum’s historian. This led to the first book about Polly’s life. Pete passed away in 1970. His successor placed a headstone on Polly’s grave. The listed date of birth was September 11, 1853, and the date of death was November 6, 1933.

In the 1980s, James Campbell fixed Polly’s cabin and led efforts to have the homestead become a memorial. He also brought Polly’s remains back to the Salmon Canyon and buried them at her old homestead. The Idaho State Historical Society named the Polly Bemis Ranch a place of historical significance. In 1987, the Federal Department of the Interior recognized Polly’s homestead as an Idaho state heritage site. At the memorial ceremony, Idaho governor Cecil Andrus announced that “The history of Polly Bemis is a great part of the legacy of central Idaho. She is the foremost pioneer on the rugged Salmon River” [20]. In 1988, Polly Bemis’ Ranch was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1996, Polly became a member of the Idaho Hall of Fame. Later, Dr. Priscilla Wegars started a course at the University of Idaho which included fieldwork: Polly Bemis’ World [21].

The Unanswered Question – Where Did She Come From?

Those who are familiar with Chinese must wonder: Lalu Nathoy sounds nothing like a Chinese name, was she actually Chinese? She was Chinese, but looking at her high cheekbones, she may not have been Han Chinese.

Although Polly’s place of birth was listed as “Pekin” in the 1880 census, researchers do not believe that this was her true birthplace. Most believe this was instead the result of a lack of understanding about China among local census takers, who used Pekin to represent the entirety of northern China to simplify the record [22]. Ruthanne Lum McCunn, the author of Thousand Pieces of Gold, once contacted the Chinese translator of her book to uncover the mystery of Polly’s hometown and ethnicity, based on her original name of Lalu Nathoy. According to Huang Youtu, a scholar and researcher of Mongolian and North Asian peoples at Beijing University, “Lalu” has two meanings: Islam or longevity. Based on Polly’s name, appearance, and scattered information about life in her hometown, Huang believed that Polly could have been a member of Mongolian or other related ethnic minorities in northeastern China, and was possibly a Daur [23]. Upon further comparison between the habitat and lifestyle of the Daur and Polly’s experiences, we see the following: she felt distanced from the other Chinese in Warren, who came from the southern Guangdong province; she quickly acclimated to Idaho’s environment, including the harsh winters; she loved farm life as well as hunting and fishing; she was a generous host and enthusiastic towards helping others. All seem to point towards signs of a Daur bloodline.

Coincidentally, the author of this text lived in Morindawa Daur Autonomous Banner, the region with the highest Daur population in China, and also traveled through the winding canyons of the upper Salmon River. The natural environment in these two regions certainly bears similarities. Most notably, the view of the northern mountains and rivers in the evening of those long summers gave the author a familiar feeling and evoked memories of the Morindawa Banner. To take the investigation a step further, the author reached out to native speakers of the Mongolian and Daur languages, asking if Lalu Nathoy is similar to names given to girls in their mother tongue. The answer was negative. The Daur pointed out: according to their customs, girls were viewed more highly in families than boys were, and a girl would never be sold. It was also noted that Polly used to have bound feet, another piece of evidence against the assumption that she was of Daur origin: Mongolian and Daur girls never had a tradition of foot binding.

Perhaps we will never know who Polly really was, or what corner of China she came from. However, Polly has left us with an extremely rich history. She did not receive any formal education and learned English entirely through interactions with others. The environment she lived in was harsh and unforgiving, and nothing came by without hard work. In the time she lived, Chinese women faced discrimination in the forms of both racism and sexism and had the lowest social status in the eyes of many of their contemporaries. She overcame obstacles with every single step she took. Most impressive of all, she completely shattered people’s perceptions of the Chinese and received the respect of everyone she interacted with. Among the anti-Chinese sentiment of the period she lived in, others once stepped in to defend her by saying she “has yellow skin, but a white heart encased in a sheathing of gold” [24]. Despite the obvious white supremacist undertones of this statement, it serves as an affirmation of Polly’s character and how others felt about her. In 1987, half a century after she passed away, her friend Fred Shiefer said at the opening ceremony of the Polly Memorial that, “I don’t think there is a better person than Polly Bemis. There couldn’t have been. Polly was one of the nicest person I’ve ever met” [25]. Governor Cecil Andrus’ statement is another clear recognition and commendation of her contribution to the history of the State of Idaho as a prominent pioneer.

On August 10, 2021, Idaho officials unveiled a life-sized bronze statue of Polly in front of the State Capitol and proclaimed the day as Polly Bemis Day.

“Today you will observe that Polly is back, 97 years later,” said David Leroy, a former Idaho Lieutenant Governor who was the emcee of the ceremony. “Polly is back,” he announced. The statue will be placed at the Bemis Ranch to honor the life and accomplishments of this noted pioneer woman and Chinese American. Polly’ story is also now part of the congressional record, read into it by U.S. Senator Jim Risch, R-Idaho.

Read more here: https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/local/article253401705.html#storylink=cpy

References

- Countess Eleanor Gizycka: Dairy on the Salmon River Part II, Field and Stream, June 1923, 187-188

- Sister M Alfreda Elsensohn: Idaho County’s Most Romantic Character: Polly Bemis,Cottonwood, Idaho: Idaho Corp. of Benedictine Sisters. 1979

- Ruthanne Lum McCunn: Thousand Pieces of Gold. San Francisco, California: Design Enterprises of San Francisco. 1981

- Katy Fry: Polly Bemis, Pedagogy, and Multiculturalism in the Classroom, in CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 10.2,2008 https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1352

- Ruthanne Lum McCunn: Reclaiming Polly Bemis: China’s Daughter, Idaho’s Legendary Pioneer, in: Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 24(1), 2003 p77-100, 96

- Ruthanne Lum McCunn Webpage: http://www.mccunn.com/PollyPic.html

- Gold Rush Days Ghost Towns Warren, http://idahoptv.org/outdoors/shows/ghosttowns/warren.cfm

- McCunn,2003,79-80

- Kathleen Prouty: Charlie and Polly Bemis in Warrens,USDA Forest Service Payette National Forest, Heritage Program, July 2002

http://www.secesh.net/History/CharlieandPollyBemis.htm

- U.S. Census, Washington (Warrens) Precinct, Idaho County, Idaho Territory,1880

- McCunn,2003,82

- Priscilla Wegars: Polly Bemis, Lurid Life or Literary Legend, in: Glenda Riley, Richard W. Etulain ed: Wild Women of the Old West, Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2003, 45-68,51

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geary_Act

- Equal Justice Initiative A History of Racial Injustice

https://racialinjustice.eji.org/timeline/03-01/

- Information in the case of U.S. v. Polly Bemis

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/298171

- McCunn,2003,85

- Wegars,2003,52

- Ibid.,58-59

- Thomson Gale: Alien Land Laws, 2008 https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/alien-land-laws

- McCunn,2003,95

- University of Idaho Community Enrichment Program, July 8-10, 2002 http://webpages.uidaho.edu/aacc/tour2002.htm

- McCunn,2003,91

- Ibid.,94

- Wegars,2003,64

- Ibid.,67

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polly_Bemis

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polly_Bemis_House

ABSTRACT

Polly Bemis, also known as Lalu Nathoy, was reputed to be the most famous Chinese woman in the Pacific Northwest. Born to a poor farming family of Northern China, she was smuggled into the US in 1872 and sold to a Chinese saloon owner in a mining camp, now Warren, Idaho. She was illiterate and, due to her different dialect, could not even communicate with other Chinese miners. Polly met Charlie Bemis who later became her life-long companion. By 1880, she had obtained her freedom and was running a boarding house. Polly and Charlie married in 1894 and moved to a place 17 miles north in the Salmon River wilderness. Together, Charlie and Polly Bemis filed a mining claim, built a house, cultivated a garden and an orchard, and hosted visitors from the town and river travelers at their ranch. In 1911 a stream flowing through the place was named Polly Creek. After their home burned down in 1922 and Charlie’s death two months later, Polly took the initiative to have her house rebuilt. She continuously lived by the river until three months before her passing away in November 1933. With her pioneer spirits of courage, perseverance, and diligence, Polly Bemis overcame the extreme hardship throughout her life. She was a true trail blazer not only for settlers in the rugged Salmon River, but also for many Chinese American women. To recognize her unique and significant contribution, Polly Bemis was inducted into the Idaho Hall of Fame in 1996.