Author: Qian Huang

Editor: Qiang Fang

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

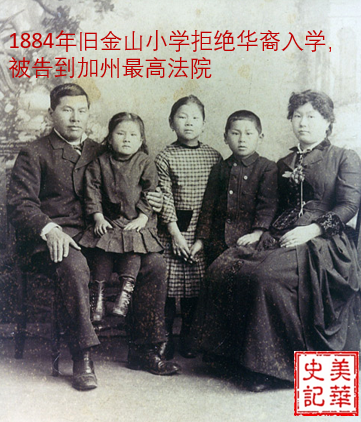

In 1884, Mamie, then eight years old, was denied admission to the Spring Valley School, because of her Chinese ancestry. Her parents sued the San Francisco Board of Education. On January 9, 1885, Supreme Court Justice McGuire handed down the decision in favor of the Tapes. After the decision, the San Francisco school board established a separate school system for Chinese and other “Mongolian” children. Only 69 years later in 1954, racially segregated public schools were ruled out by the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

~~~

“I would rather go to prison than let Chinese enroll!”-Danielwitz, member of the San Francisco Board of Education Committee, 1884

Is it truly that disgraceful to be Chinese? Aren’t we all humans made by God? What right do you have to stop her from going to school just because she is of Chinese descent? -Mary Tape, 1884

“100 years ago, Principal Hurley would stand in front of the school to prevent me from entering. Today, my duty is to stand in front of the school and welcome all students!”-Principal Lonnie Chin of San Francisco Spring Valley Elementary School, 1997

Segregation against Chinese school children began in none other than San Francisco, United States.

A wealthy Chinese family immigrated into the United States, with American-born Chinese sons and daughters.

The following is a photo of the Chinese family in San Francisco around 1885. The children’s mother and father are Joseph and Mary Tape, and the girl in the middle is Mamie.

Picture 1: Joseph Tape’s family

Picture 2: Mamie Tape

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tape_v._Hurley

Joseph Tape came from Fushi Village, Xinning County, Guangdong Province. He immigrated to the United States at the age of 12. He started working as a helper on a farm owned by a Scottish immigrant family by the name of Sterling near San Francisco. When he grew up, he drove for the Sterling family farm as a milk delivery man in San Francisco. Later he bought his own transportation to act as an intermediary for Chinese immigrants coming to the US.

Mary was from Shanghai, and she grew up in a church orphanage in San Francisco. In the spring of 1875, Joseph Tape met Mary while delivering milk. Both of them grew up in American households and had been accustomed to American culture and lifestyle. In the vast sea of people in a foreign country, two young hearts rarely meet so opportunely. From acquaintances to lovers, the couple got married on November 16th that year. They decided to start a family and raise children in a local white community. Joseph Tape and Mary were not only fluent in English, but they were also Christians, so the wedding was held in a church, and American media described their speech, manners, dress and living habits as conforming to American social customs. [1]

In 1882, anti-Chinese hate swept across the United States, and the U.S. government enacted legislation to prohibit Chinese workers from entering the United States. At the time, most Chinese folks in the United States were miners, railroad workers, laundry workers, fishermen or farmers. They often had no chance of marrying or the opportunity to learn English. They remained economically and socially impoverished. That is why families like Joseph Tape and his wife were more economically well-off and more culturally assimilated American-Chinese families.

Joseph Tape and his wife knew that they would not be allowed to attend US public schools because they were born in China. But their children were not only born in the United States, but also grew up in a white area. Their children played with and lived alongside white children, and there was no language barrier. Furthermore, by 1884, Joseph Tape had lived in California for 18 years, 15 of which were in San Francisco. The family paid their taxes and followed the law, so they believed that there should be no problem for their children to go to local public schools.

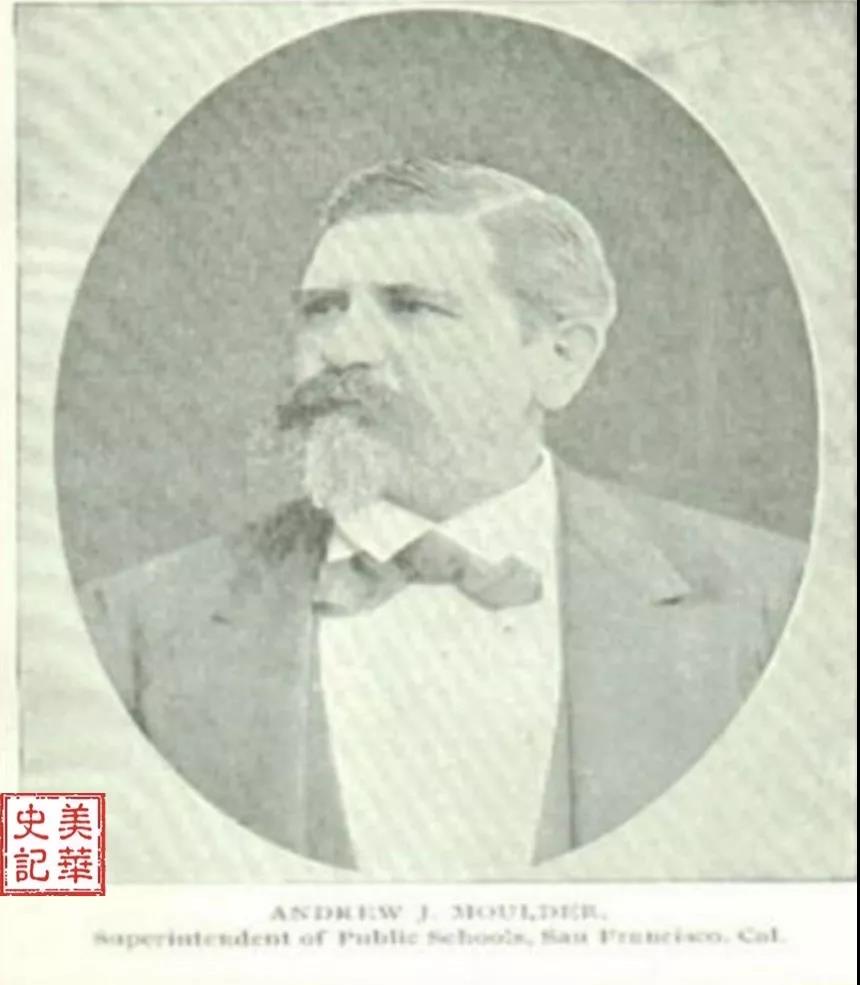

On the morning of September 1884, Mary dressed her 8-year-old daughter Mamie in a pretty dress and then tied a bow in her hair. The young mother took her little girl to register for school at Spring Valley Elementary School. The school was located on Union Street in San Francisco. The school building was a one-floor wooden house. The principal was a lady named Jennie Hurley. At that time, the school was all white. Faced with a Chinese mother taking her daughter to school, Headmaster Hurley was at a loss, so she asked the superintendent Andrew Jackson Moulder for instructions. [2]

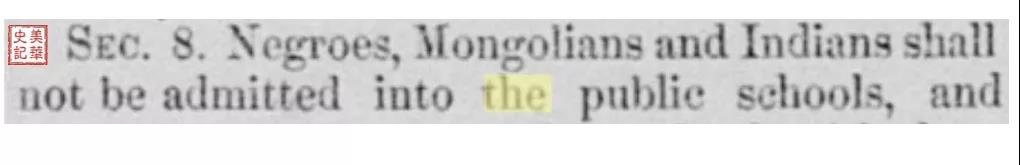

People of color prohibited from going to public schools

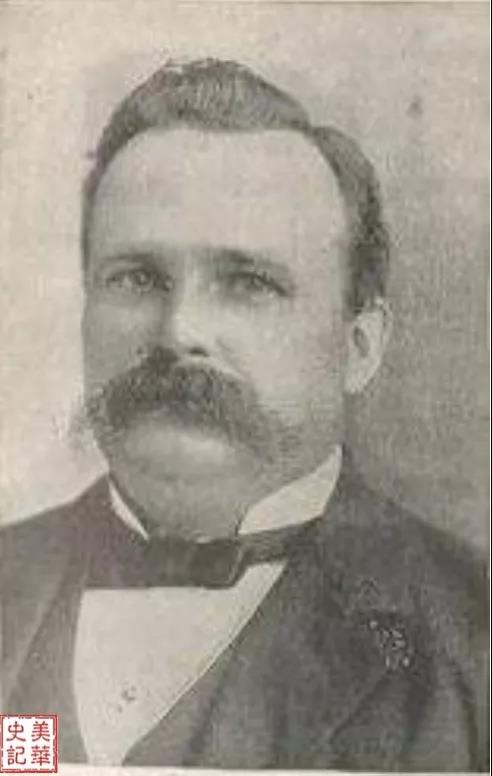

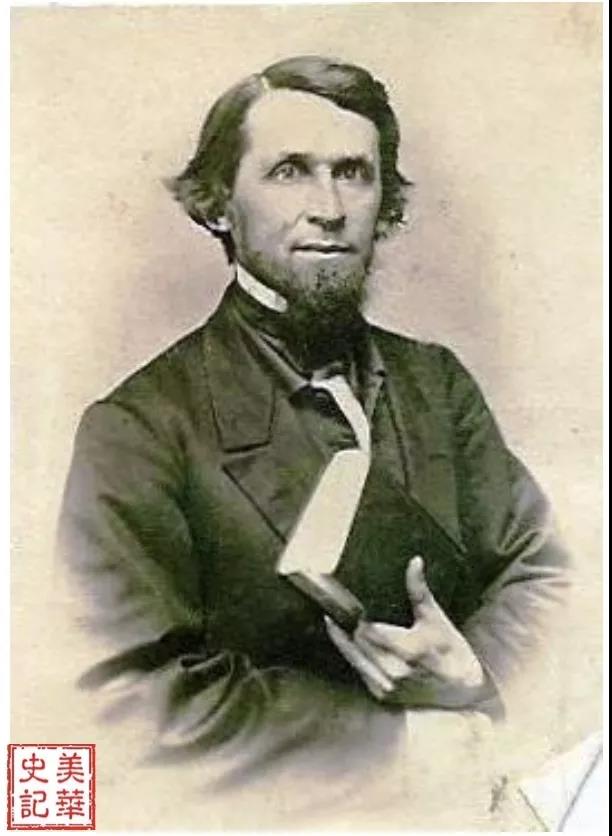

Picture 3: Moulder, Superintendent of the San Francisco Department of Education

http://slideplayer.com/slide/6076034/

In 1860, 35-year-old superintendent Moulder promoted the enactment of the California law prohibiting children of color from enrolling in public schools. Article 8 of the law stipulates: “Negroes, Mongolians and Indians are not allowed to enter public schools…” [2] (Mongolians were considered a ‘yellow’ race. At the time, the term “Mongolians” and “Chinese” were synonymous in the US. After the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King in the 1960s, it was forbidden to use the derogatory “Mongolians” and “Easterners” and “Orientals” to refer to Chinese people.)

Under the lobbying of Superintendent Moulder, the state legislature officially passed a bill prohibiting Black people, Mongolians (including Chinese), and Indians from entering public schools in 1860. If a school violated this law, it would face severe punishment.

Picture 4: Original text of the bill

The segregated education system regulated that education funding was based only on the number of white children in the district. In other words, even though people of color paid the same taxes as whites, California did not account for children of color at all when it established the public education system.

Moulder insisted on prohibiting African-Americans, Chinese and Indians from enrolling in white schools [3]. Moulder came from the former slave states of the southern United States. As a wealthy lawyer, he had always been active in California politics, especially in the education field. That was his specialty.

This was how San Francisco Superintendent Moulder refused the 7-year-old Mamie to study at Spring Valley Elementary School.

Using the law to fight against segregation

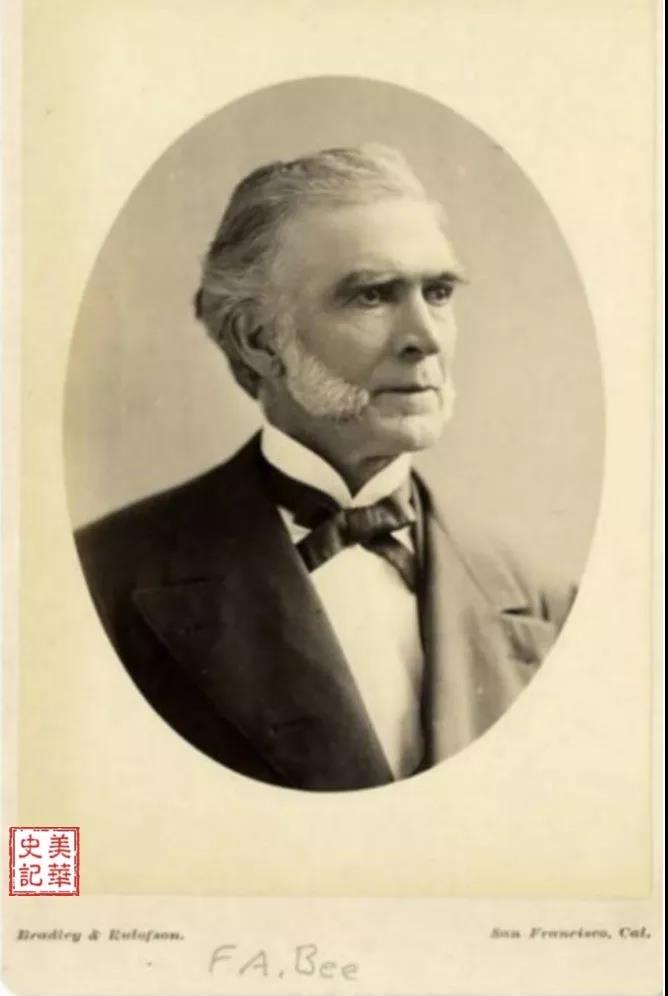

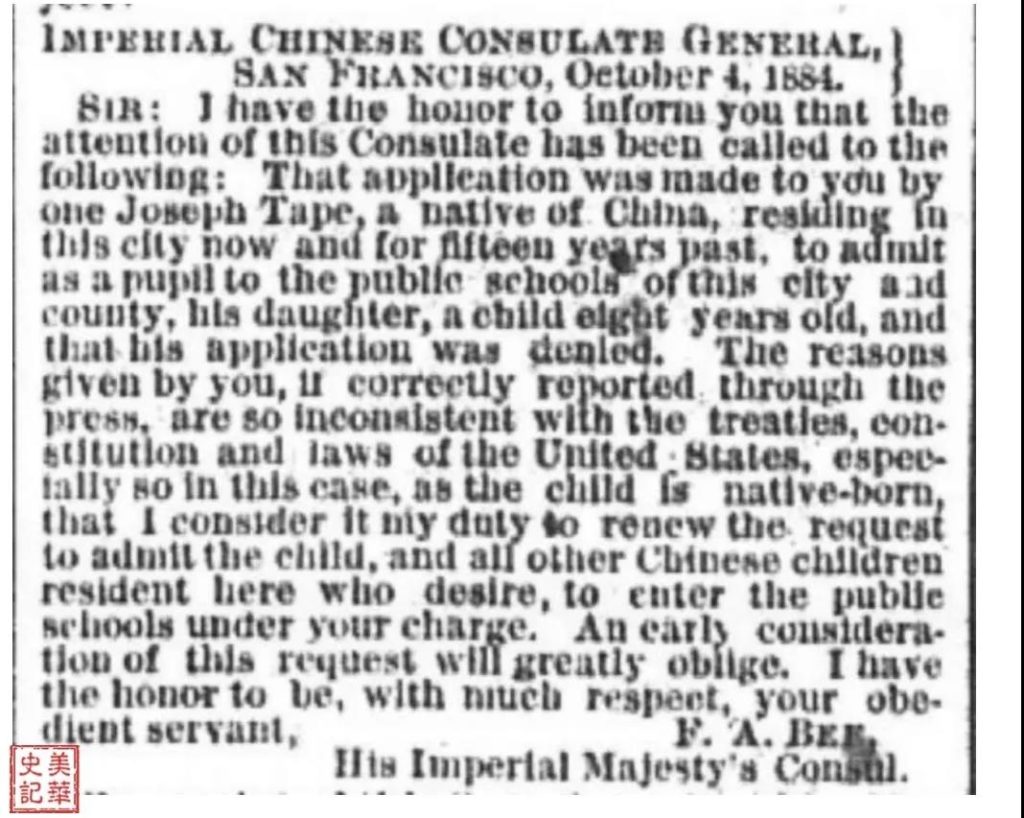

Mamie’s parents approached the Qing consulate in San Francisco for help. They were received by lawyer Frederick Bee, a consulate official.

Picture 5: Lawyer Frederick Bee, an official of the Qing consulate

http://www.frederickbee.com(Meihua Shiji has a special article discussing Frederick Bee)

After hearing the statements of Mamie’s parents, Frederick Bee immediately raised a pen and lodged a protest against the San Francisco Department of Education. The lawyer pointed out in an official letter to the Superintendent of San Francisco, California that refusing to allow Mamie an education violated the current treaty between China and the United States with regards to equal treatment, violated the US Constitution, and violated California law. Bee also emphasized that Mamie was born in the United States and should be treated with the same respect as an American. [4]

Picture 6: Protest letter by Frederick Bee to the San Francisco and California Department of Education

After receiving the official letter from Bee, the San Francisco Board of Education held a meeting to discuss whether to accept Mamie into public schools and conducted a vote.

The result of this vote was 8:3. Eight of the eleven committee members supported the school’s rejection of Mamie’s admission, and only three committee members believed that public schools should accept her. [4]

Isidor Danielwitz, one of the eleven Board of Education committee members, even said that he would rather go to prison than accept Chinese children in public schools. Another member of the Education Committee was Dr. Charles Cleveland. For the last 20 years, and even before the anti-Chinese movement, he had always insisted on opposing Chinese immigrants and even wrote articles on his prejudice against them. However, on the issue of education, he believed that if the child was born in the United States, he/she should be educated regardless of race. Unfortunately, the committee members who agreed with Dr. Cleveland’s views were very limited.

Principal Hurley finally decided not to accept Mamie Xiao. The Qing consulate protested to the San Francisco Education Bureau, but to no avail. The San Francisco Education Bureau refused to enroll Mamie Xiao. Superintendent Moulder reported the matter to his superior, the superintendent of California, Welker. However, the state-level superintendent also refused to accept Chinese children in public schools.

Speaking of lawyer Frederick Bee’s protests, the California Department of Education Supervisor Wilke’s attitude was even more resolute. He told the media: “I doubt that the Federal Court has the power to require California to spend money on the education of these Chinese children. Moreover, our Constitution has declared that the existence of the Chinese is a danger to California’s welfare.”

State Superintendent Wilke’s constitution was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. His resentful attitude also reveals the source of the problem: since the Chinese Exclusion Act officially sounded the clarion call to discriminate against the Chinese, companies prohibited Chinese workers, schools prohibited Chinese children, and hospitals prohibited Chinese patients.

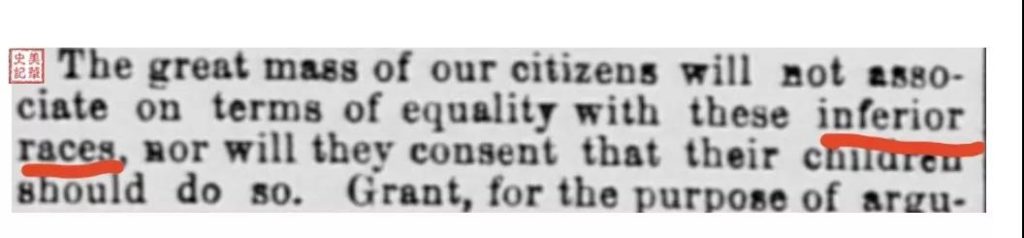

The California media publicly stated: “The great mass of our citizens will not associate on terms of equality with these inferior races, nor will they consent that their children should do so.” The original text is shown in the figure:

Picture 7: Text regarding “inferior nations”

At that time, the media reported multitudinously on the problem of Chinese children entering public schools. Some of these headlines included: “Education Bureau,” “China Problem Again,” “Last Night’s Long Meeting,” “Education Bureau refuses to listen to US Born Chinese about school admission request.”

When Mamie’s parents tried appealing to the Bureau of Education, it did not work. From the California Bureau of Education to the San Francisco City Bureau of Education to the one school principal, Chinese children were not allowed. But Mamie’s parents did not give up so easily. Following the advice of lawyer Frederick Bee, an official of the consulate, Mamie’s father Joseph Tape approached the lawyer William Gibson and asked him to represent him in court.

At the time, it was not easy to find a lawyer who was willing to file a lawsuit on behalf of the Chinese. So what was the background of this lawyer, William Gibson?

William Gibson was born in China and graduated from Harvard Law School. Attorney Gibson’s parents had traveled across the ocean to Shanghai in 1855 as missionaries.

Attorney Gibson pointed out: The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ensures that all citizens have equal protection of rights under the law. The prohibiting Mamie’s enrollment in school not only violated the California School Act of 1880 but also violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

With the help of lawyer Gibson and lawyer Bee of the Chinese Consulate, Mamie’s parents decided to file a lawsuit in the California State Court to fight for the right of Chinese children to enter public schools.

In January 1885, Judge James G. Maguire declared that the Mamie family won the case. Thirteen years later, Judge Maguire ran for governor of California. In his judgment, Judge Maguire cited the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution that citizens enjoy protected equal rights. He asked Spring Valley School to accept Mamie and all other Chinese children who enrolled.

Picture 8: Judge Maguire of the California State Court

Judge Maguire’s decision to allow Chinese children to enter public schools angered Moulder and the San Francisco Board of Education. A member of the Education Bureau resigned immediately in protest. The committee solemnly declared its refusal to accept the court’s decision.

The Education Bureau’s pledge would carry out its discrimination against Chinese children to the very end.

“I would rather go to jail than admit Chinese students,” said Moulder as he appealed to the California Supreme Court. However, on March 3, 1885, the California Supreme Court declared that Judge Maguire’s judgment would be upheld.

Would superintendent Moulder finally drop his case? Unfortunately not. Moulder held extreme power in the education system, but most importantly, he was stubbornly set on his goal and spared no effort to prevent Chinese children from enrolling. He racked his brains and finally came up with a scheme: quickly push a state bill to provide a separate school for Chinese children. In this way, the current school could continue to admit only white students. Such segregated schools prevailed for many years in the southern United States.

Just two months after Judge Maguire ruled that Chinese children were allowed to enter public schools, in early April 1885, the primary school for Chinese children had not yet opened, so Mamie had to enroll at Spring Valley School. This time principal Hurley could not reject Mamie on the basis of her Chinese descent. However, the principal came up with new excuses to reject Mamie such as:

1. The student quota is full.

2. Mamie has no vaccination certificate.

Mamie’s mother became indignant at such blatant discrimination. She wrote in a letter to California media, “The persecution Moulder has shown my daughter is something I would not wish upon my worst enemy! Is it truly that disgraceful to be Chinese? Aren’t we all humans made by God? What right do you have to stop her from going to school just because she is of Chinese descent?.. Do you think that forcing my children to go so far away just to get an education is Christian behavior? … I will show the world that there is no justice under the rule of racially prejudiced people!”[14]

On the fifth day that Mamie’s mother wrote the letter, which was April 13, 1885, the elementary school for Chinese children opened under the rushed supervision of the Education Bureau. Mamie and her younger brother were some of the first students sent to the Chinese-only school.

Under Moulder’s control, the Education Bureau established Chinese schools to prevent Chinese from entering formal public schools. However, they still did not even allow a place for Chinese children to learn English.

In 1887, the California legislature revised the school law specifically because of the Chinese, stating that “the school management agency has the right to establish segregated schools to accommodate Indian and Chinese children. When such segregated schools are established, Indians and Chinese children are not allowed to enroll in any other school.”

Chinese children can only go to Chinese schools

Although the victory won by the Mamie family was only a partial victory, it was still won. In order to keep Chinese children out of white schools, the Education Bureau established separate schools for Chinese children. Prior to this, the Education Bureau, on the grounds that the funding was based on the number of white residents, required Chinese children to go to private schools or church schools to learn the Bible. Although most of the Chinese also paid taxes according to regulations, there were no seats for Chinese children in any public school.

What’s commendable is that when the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, some American lawyers with a sense of justice bravely challenged the segregated education system, which boosted the morale of disadvantaged groups, and gave the Chinese community hope that their rights would be protected after all.

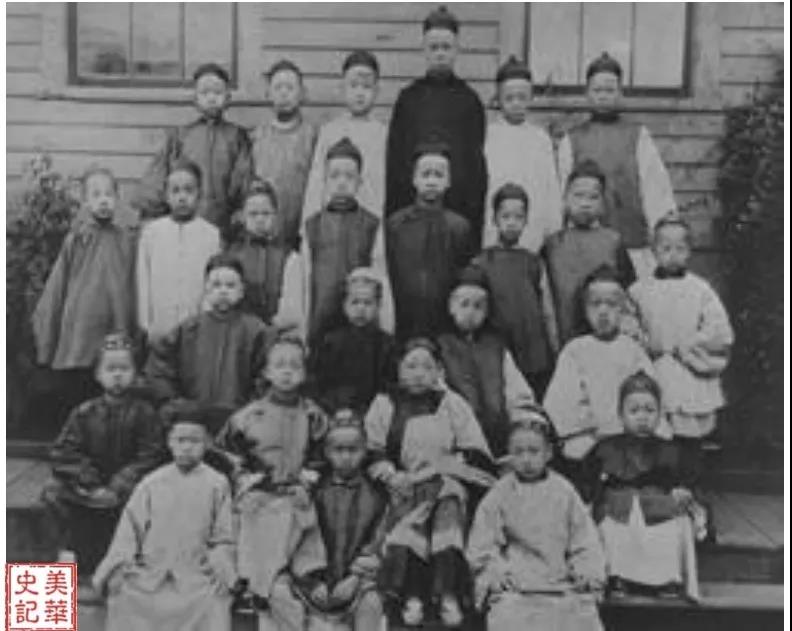

Picture 9: The woman on the left is Mamie’s mother Mary, and the boy in the back is Mamie’s younger brother Frank.

Speaking of the segregated education system, there was a segregated Chinese school known as “The Chinese School” and was later changed to Oriental Public School in 1906 in order to accept Japanese and Koreans.

The Chinese School was first established by the San Francisco Bureau of Education in September 1859. Four months later, the Bureau of Education closed its doors because of lack of funds. On May 28, 1878, the Chinese collective entrusted lawyer Brooke to appeal to the Education Bureau to open a school for the Chinese. However, the Education Bureau continuously ignored it until Mamie’s parents won the lawsuit. [6]

Figure 10.:A school in San Francisco opened solely for Chinese children. The girl in the middle of the second row is Mamie and her brother Frank is on the right.

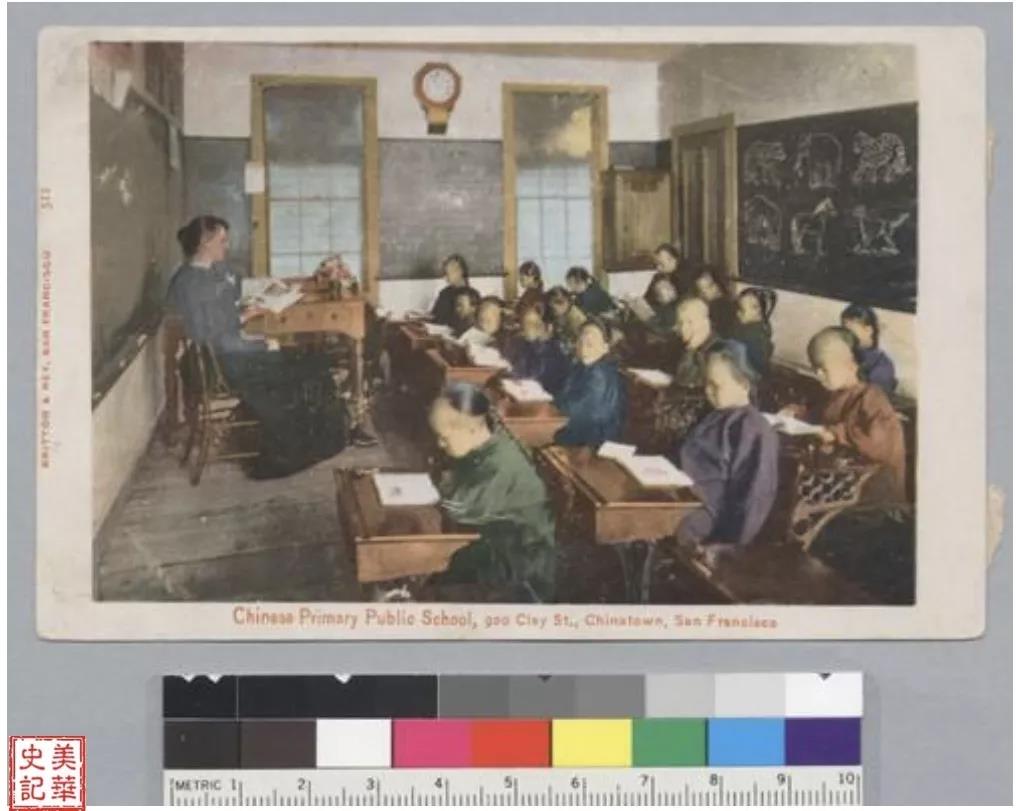

Picture 11: San Francisco Chinatown Elementary School From http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

Picture 12: Postcard, Chinese primary school classroom from http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

In 1906, the United States was set to introduce the Immigration Act of 1924, but the collapse of houses after the San Francisco earthquake forced many Chinese to move out of Chinatown, so schools had spare seats. The Education Bureau then arranged for Japanese and Korean children to attend Chinese schools, and at the same time changed its name to “Oriental Public Schools.”

Figure 13: San Francisco’s Chinatown Oriental Public School pledges to the American flag. From http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

The San Francisco Presbyterian Church in Chinatown was the first Chinese church in North America and opened in 1853. The founder was a man by the name of Pastor William Spear. He was also the uncle of James Buchanan, the 15th President of the United States. The other head of church was Augustus Loomis, who was excited because he and Otis Gibson (the father of the young Gibson lawyer who litigated the Mamie family) went to the congressional hearing to testify for the Chinese when discussing the Chinese Exclusion Act. This provoked the anger of anti-Chinese Americans.

This is a picture of the school run by the San Francisco Presbyterian Chinatown Church for Chinese children, taken in 1887:

Picture 14: San Francisco Presbyterian Chinatown Church runs a school for Chinese children from http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

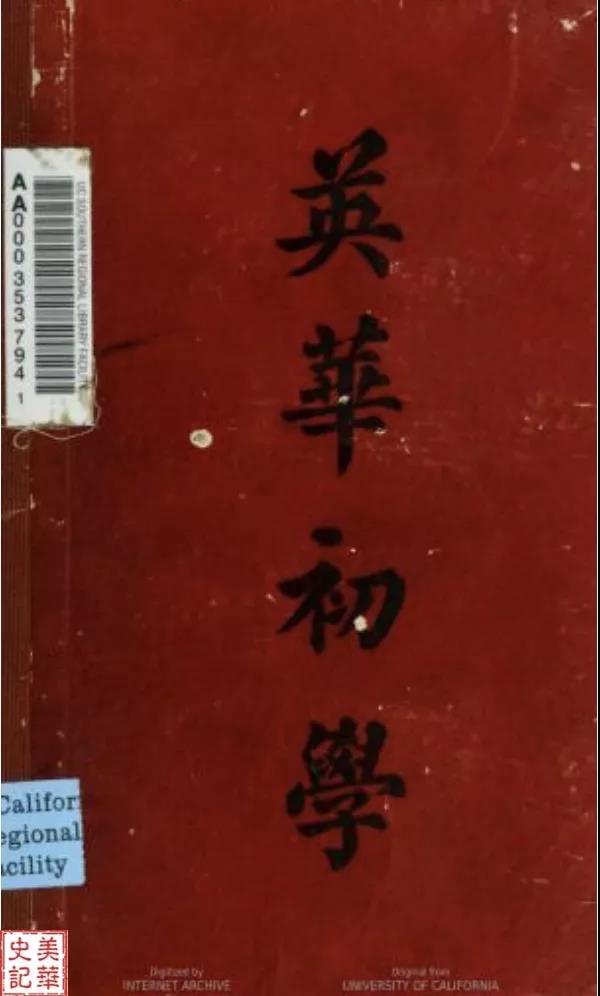

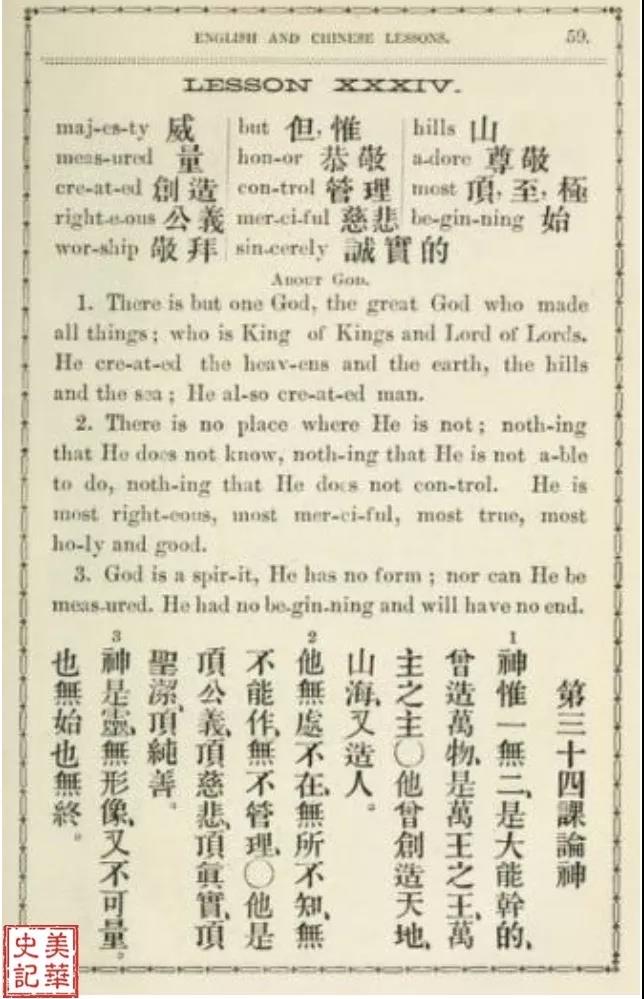

In 1859, Pastor Spear started to run schools for Chinese children in the basement of his Chinatown church. However, the school mainly taught the Bible in hopes that the Chinese would return to China to spread Christianity. Before Mamie’s mother won the case against the San Francisco Board of Education, many Chinese children had no school to go to, so they had to rely on this mission school in Chinatown to learn Bible English.

Picture 15: Pastor Spear

Picture 16: Augustus Loomis

Figure 17. Textbook cover of the Chinatown Mission School

Figure 18. Textbook for teaching the Bible at Chinatown Mission School

In 1873, 1,300 Chinese residents of California submitted a letter to the local legislature, stating that they paid taxes in accordance with the law, and thus required the opening of schools to enroll 3,000 local Chinese children. The appeal of the Chinese residents was supported by the pastor of the church in Chinatown. However, the Education Bureau turned a blind eye to this appeal. A report from the San Francisco Department of Education reads: “Tightly control the gates of our public schools and don’t let them in.” “No matter how urgent and how desperate their voices are, we must implement the law of self-survival. … to practice the iron law… to protect yourself from the invasion of Mongols’ barbarism.”[4]

The six major companies of the Chinese People’s Organization, which was the predecessor of the current Zhonghua Institute, also opened schools for the Chinese to learn English with the assistance of the Qing consulate.

Picture 19: 1908 Chinatown Chinese School from http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

Many ethnicities, one classroom

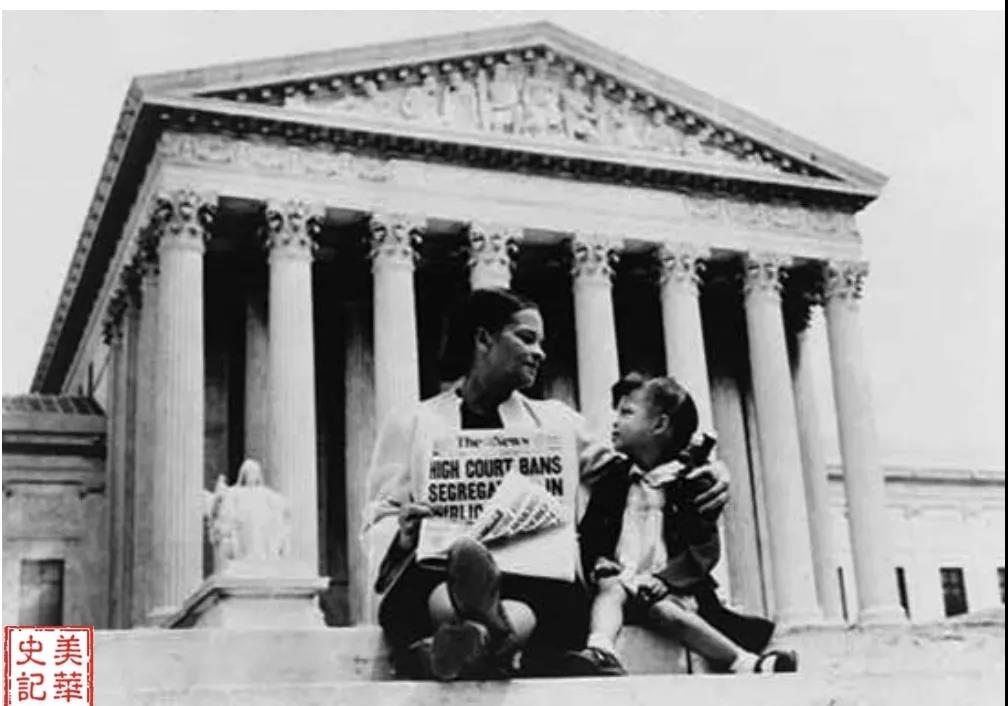

In the 1920s, because the only Chinese school in Chinatown could not accommodate the students who signed up, the Education Bureau had to arrange Chinese students to enroll in schools near Chinatown. Since then, most of the Chinese children in San Francisco gradually entered public schools for students of different ethnicities. In 1944, the Mexican couple by the name of Mendez sued the Board of Education for school segregation (Mendez v. Westminster) on behalf of five thousand Mexicans [11]. On June 14, 1947, California Governor Earl Warren finally signed the document. The result of the Mendez victory was turned into law–it completely overthrew the “separate and equal” education system and declared racial segregation in California public schools illegal. At this time, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, and racial segregation in California schools was banned. However, the real elimination of segregation in schools across the United States was due to the African-American Brown’s victory in 1954 against the Board of Education (Brown v. Board of Education) [12]. However let us not forget Mamie’s parents’ struggle against the segregated school system seventy years prior!

Picture 20: 2010 Obama was a victim of segregated education. Civil rights activist Mendes was awarded the Medal of Freedom.

Picture 21: Brown wins lawsuit against the Board of Education. In the picture, the little girl Linda Brown died at home in March 2018 at the age of 76.

In fact, the Mamie family was not the only Chinese family to fight against the segregated education system. Ten years before Mamie’s official lawsuit was filed, the Chinese residents of San Francisco also petitioned the government to open a school for Chinese children. In 1924, in Mississippi, two daughters of the Lum family were suddenly expelled from school on the basis of their Chinese descent. That’s when the Lum family also asked a lawyer to sue. [13]

Picture 22: The Lum daughters from Mississippi were expelled from school because of their Chinese descent.

The first Chinese teacher, the first Chinese superintendent

Picture 23: Alice Fong Yu, the first Chinese teacher in an American public school

Alice Fong Yu was the first Chinese teacher in an American public school. Born in California in 1905, her father was a mine supervisor who later opened a small grocery store. Fong Yu’s application for admission to San Francisco Teachers College in 1922 was rejected. The principal told her that she should give up her dream of being a teacher, because no school in the United States would hire her as a teacher. You Fang Yuping told the school that she planned to return to China to teach English after graduation, and had no plans to teach in the United States. Thus, she was admitted to the school and graduated in 1926. When Fong Yu interned at a Chinese school, the principal was very satisfied with her work, because the school finally had a teacher who understood the students and was able to communicate with parents. The principal informed the San Francisco University that as soon as Fong Yu graduated, the Chinese School would hire her as a teacher. As the only teacher in the school who understood Chinese, Alice Fong Yu not only taught her students, but also had the opportunity to be their counselor and caretaker.

In addition, Fong Yu became an active leader in the Chinese community. In 1996, San Francisco decided to name a school after the influential woman.

Picture 24: Alice Fong Yu School

Picture 25: Students from Alice Fong Yu Alternative School

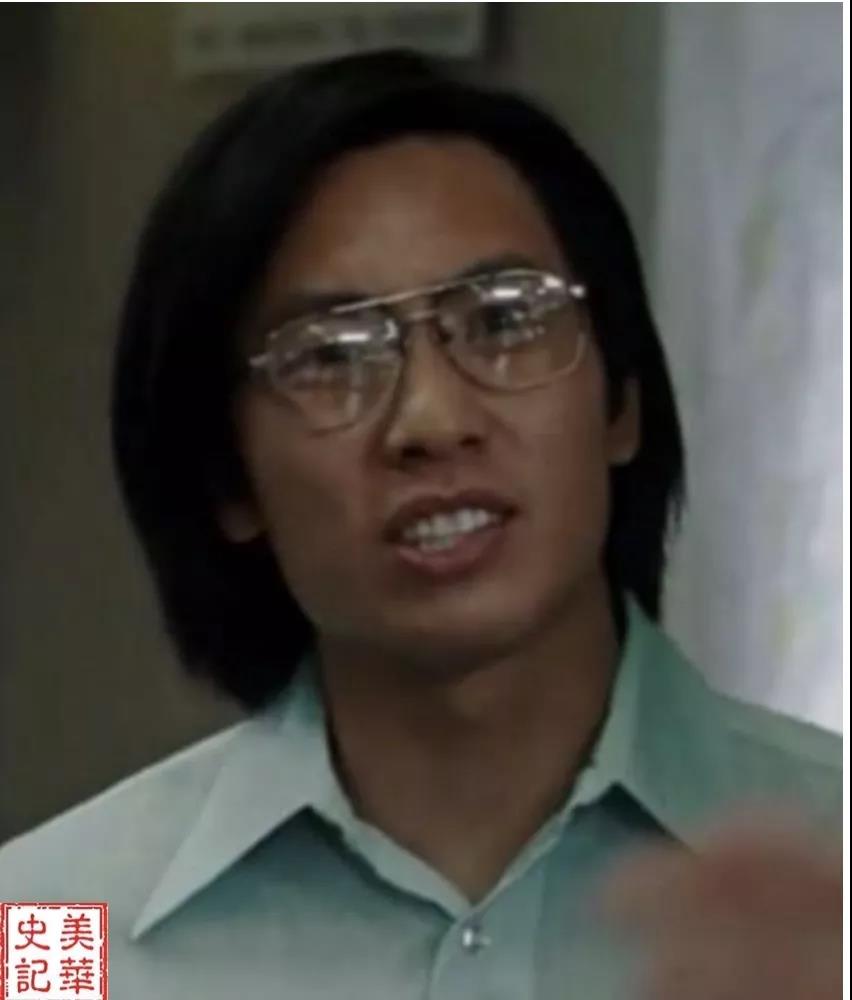

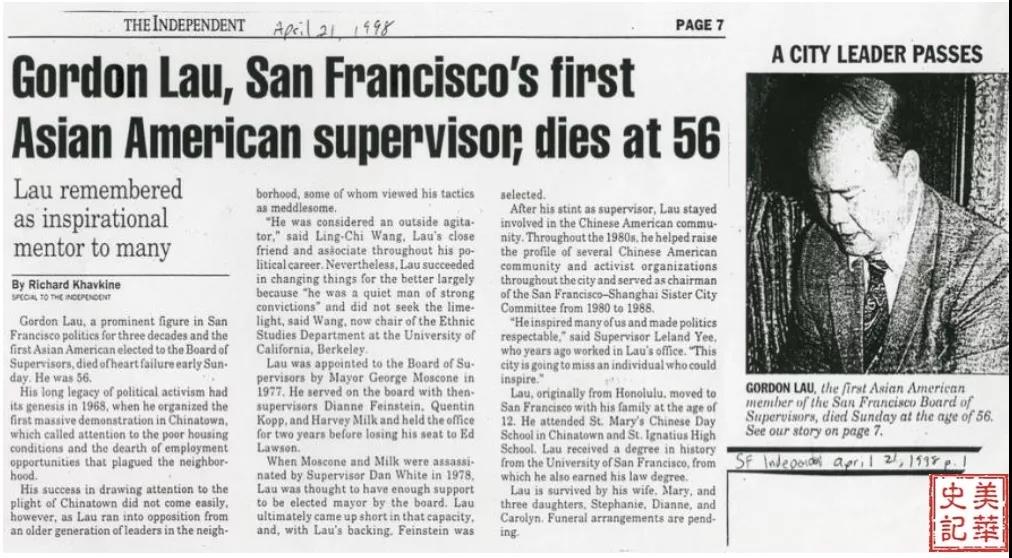

Gordon Lau was born in 1941 and was elected as the first Chinese superintendent of the San Francisco Education Bureau in 1977. The well-known Oriental Elementary School in San Francisco’s Chinatown was renamed after him.

Picture 25: Gordon Lau, the first Chinese superintendent in San Francisco

Picture 26: A newspaper about Gordon Lau

Picture 28: The former Chinese primary school is now named after Gordon Lau, the first Chinese superintendent in San Francisco

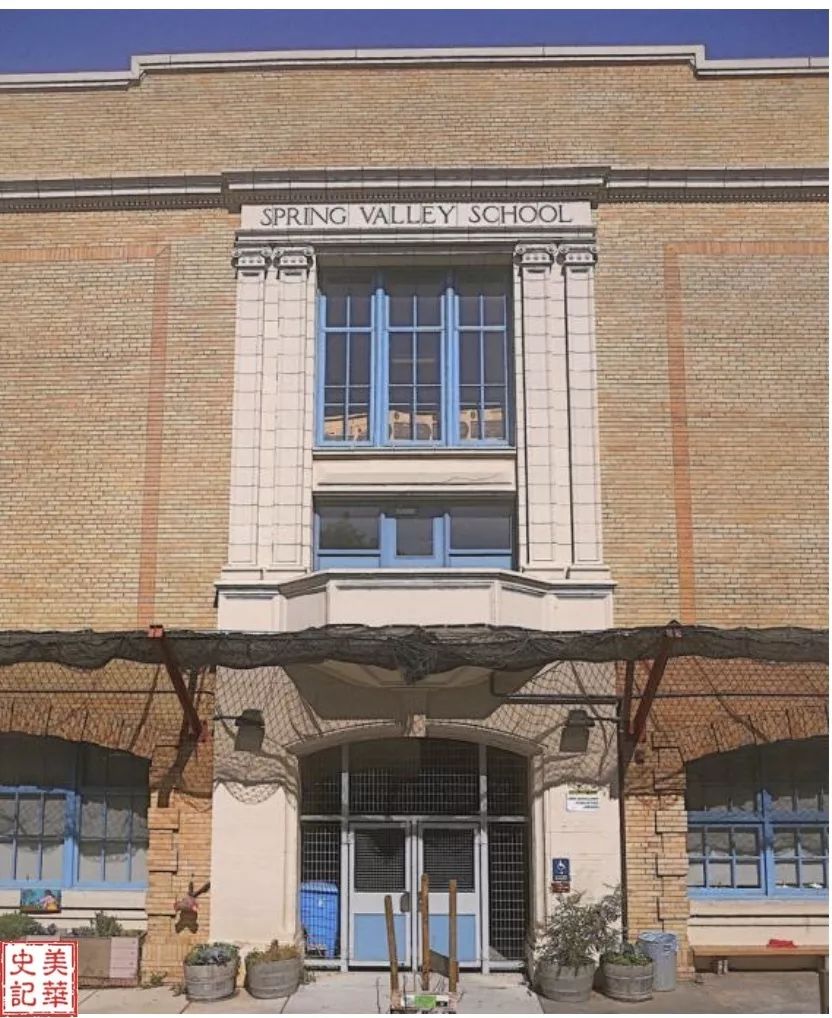

Lessons learned from Spring Valley School

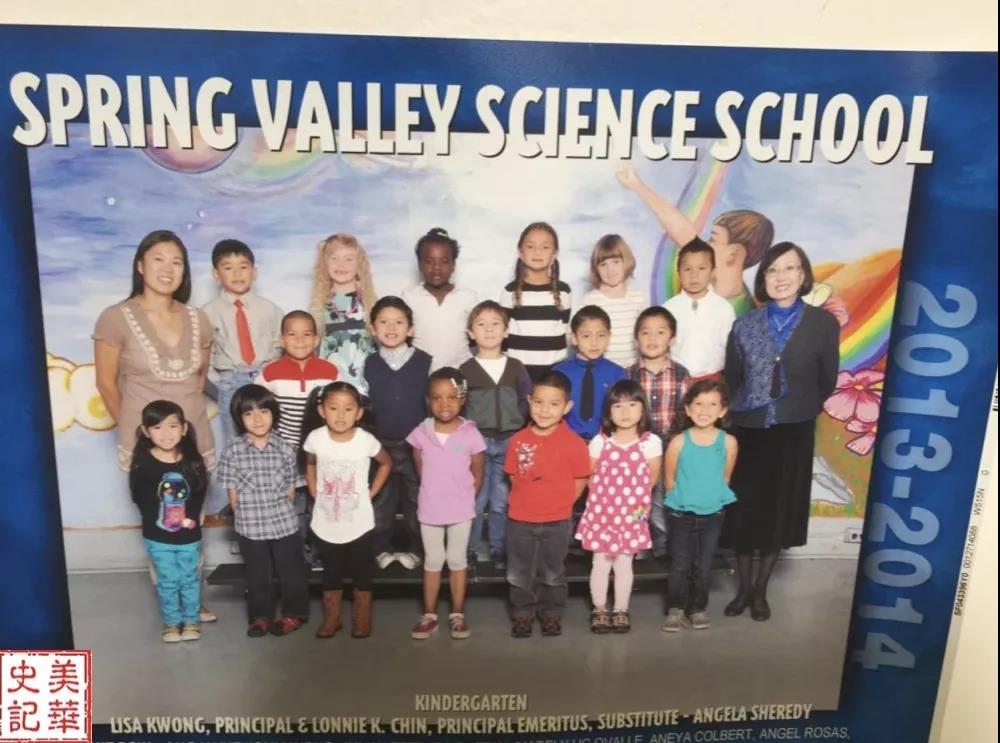

The school Mamie was prohibited from enrolling in 1884 was called Spring Valley Elementary School. Founded in 1852, the school is the only one that still exists among the seven earliest schools during California’s gold rush. The original school building had only one floor. The building we see now was built after the San Francisco earthquake and fire in 1906. [10]

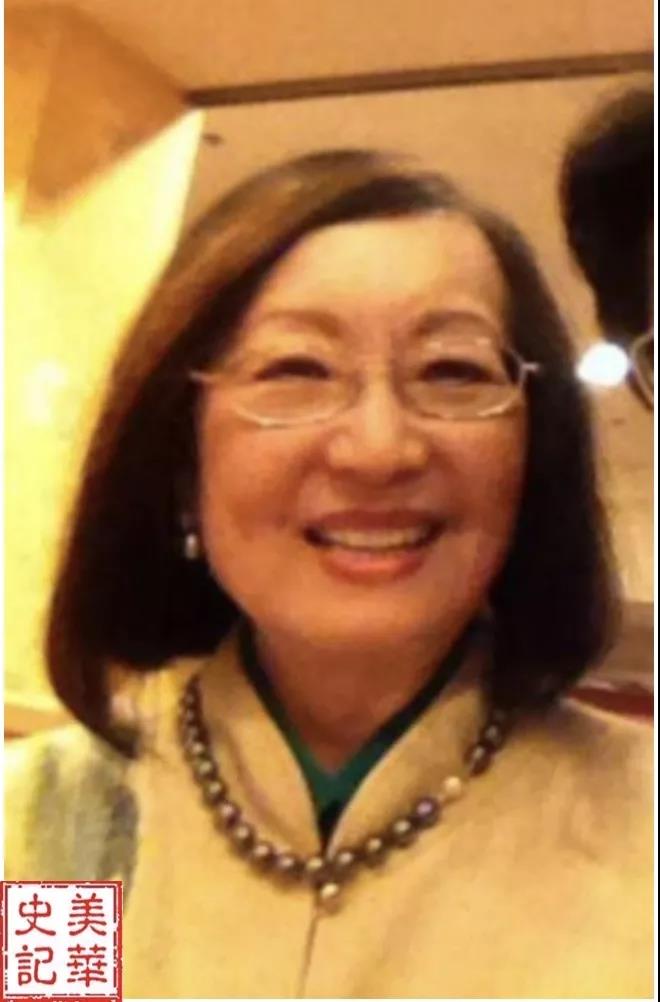

In the 1980s, Spring Valley Elementary School finally welcomed its first Chinese female principal, Lonnie Chin. After obtaining a master’s degree from Harvard University, Lonnie Chin served as the principal of Spring Valley Elementary School.

Picture 29: Lonnie Chin, principal of Spring Valley Primary School

Picture 30: Front entrance of Spring Valley Primary School

Principal Chen proudly said: “100 years ago, Principal Hurley would stand in front of the school to prevent me from entering. Today, my duty is to stand in front of the school and welcome all students!”

Picture 31: Principal Chin and the graduating kindergarten class

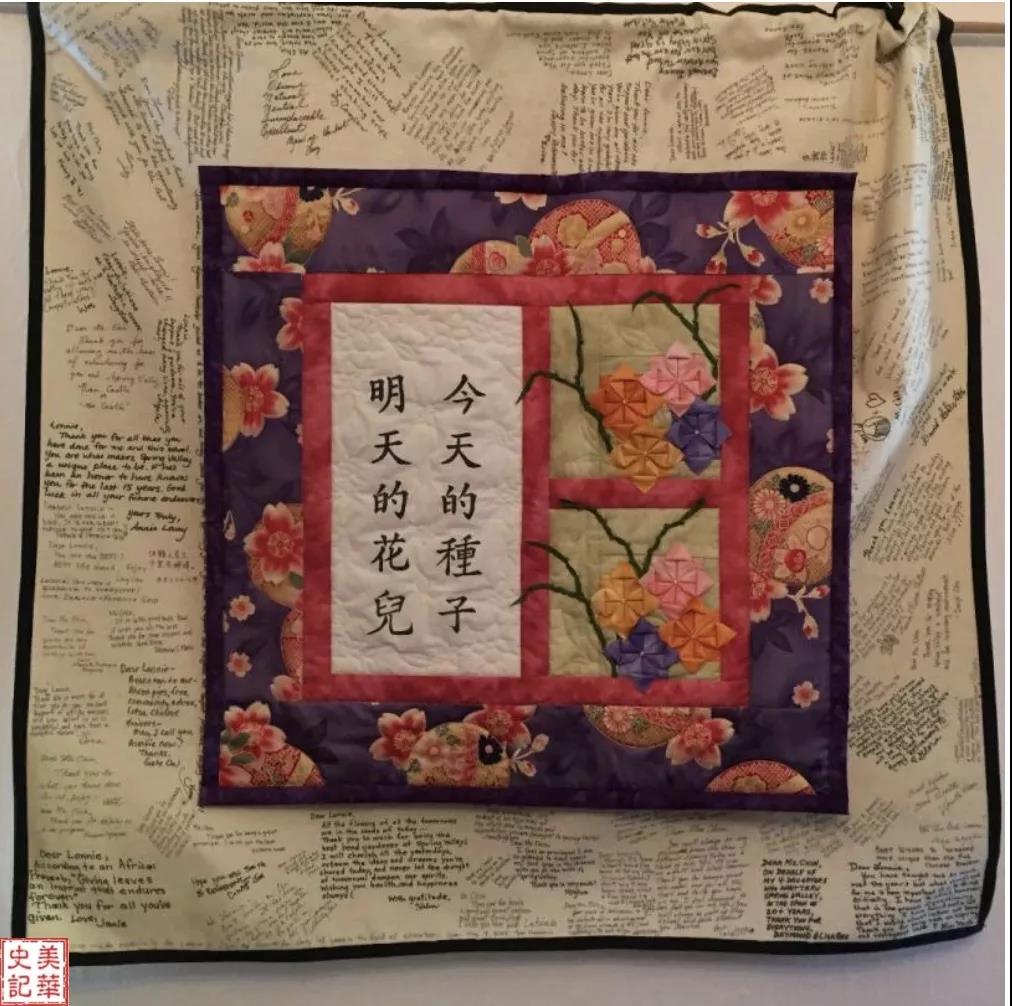

Picture 32: Gift received by Principal Chin when she retired

Principal Chin always said, “Today’s seeds are tomorrow’s flowers.” She encouraged teachers to use all of their educational resources to help develop their students’ creativity and wisdom. When she retired after serving as the principal for more than 30 years, the Education Bureau wanted to name the elementary school after her. But Principal Chin said, “The name Spring Valley Primary School has historical significance and must be preserved.”

The history of Spring Valley Elementary School tells us that the freedom and equality enjoyed by Chinese Americans today are the result of the brave struggle of our ancestors. Moreover, it reminds us that we must unite with different ethnic groups to strengthen our cause. From Mamie’s parents who sued the San Francisco Board of Education in 1884 to the Lum family in Mississippi who sued their local Board of Education; then from the Mendez family who sued the Board of Education on behalf of 5000 Mexicans in 1944 to the Brown family, this common struggle that lasted 70 years was endured so that all of our children could gain the right to go to school.

In 2017, the mayor of San Francisco was Chinese-American Li Mengxian, and the city education director was a Korean-American.

On Tuesday, January 24, 2017, the San Francisco Board of Education abolished the 1906 law: “Asian Americans can only attend Oriental public schools.” [9]

This proposal came from Ms. Emily, a Japanese-American member of the San Francisco School District.

In fact, Japanese children were not restricted to Oriental Elementary Schools, because just before the implementation of the Japanese Exclusion Act, the United States and Japan signed a Gentlemen’s Agreement to stop this bill. Under the direct supervision of President Roosevelt, Japanese children were allowed to attend regular public schools.

Japanese-American Ms. Emily said, “Our school district has a very dark history. It is important to acknowledge this history.” [9]

A teacher from Spring Valley said, “In the United States today, the racial segregation and antipathy towards the Chinese have been eliminated significantly. Although the situation has improved a lot, we still need to continue pursuing justice.”

Post-reading Thoughts:

1. From the Chinese banned from enrolling in school, to today, countless Chinese folks play a pivotal role in the field of education. How did this drastic reform happen? Is it because of hard work and perseverance? Is it that the Chinese 100 years ago were not as hardworking as other ethnic groups?

If minorities are not equally protected and represented, no matter how hard you work, there is no room for you. For example, the Chinese workers in the 19th century were diligent beyond measure, and yet they were the only ones banned from entering the United States by law.

To be a real tiger parent is not only to urge your children to study, but also to understand a truth, which is that the more equal American society is to minorities, the better development your children will have.

2. Once Chinese youth learn about the history of the segregated education system, will they doubly cherish the opportunity of education they have today?

Sources:

- Mae M. Ngai, The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2010)

- Gary Kamiya, “How early SF kept Chinese children out of the schoolhouse”

in San Francisco Chronicle, April 15, 2017

- Gary Kamiya, “How early SF kept Chinese children out of the schoolhouse”

in San Francisco Chronicle, April 29, 2017

- 傅列秘历史项目网 http://www.frederickbee.com/1884.html

- Charles J. McClain “In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle against Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America” May 3, 1994

- Joyce Kuo, “Excluded, Segregated and Forgotten: A Historical View of the Discrimination of Chinese Americans in Public Schools”

- https://poweltonhistoryblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/rev-william-speer-early-christian.html

- http://www.irwinator.com/126/wdoc198.htm

- http://www.gelfand-partners.com/2017/01/24/san-francisco-chronicle-10/

- http://www.springvalley-sfusd-ca.schoolloop.com/history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mendez_v._Westminster

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_v._Board_of_Education

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lum_v._Rice

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tape_v._Hurley

Pingback: White Paper: National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – 美华史记