Author:Qian Huang

Translator: Ella N. Wu

Lau Sing Kee (1896-1967), a World War One hero who served in the 77th Division of US Army, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the French Croix de Guerre. Although he was the first Chinese American to be decorated for his bravery in war, Lau Sing Kee is not even well-known in Chinese American Communities. Stevie Wonder, however, has immortalized him in his song “Black Man.” The lyrics are, “Who was the soldier of Company G who won high honors for his courage and heroism in World War 1? Sing Kee – a yellow man.”

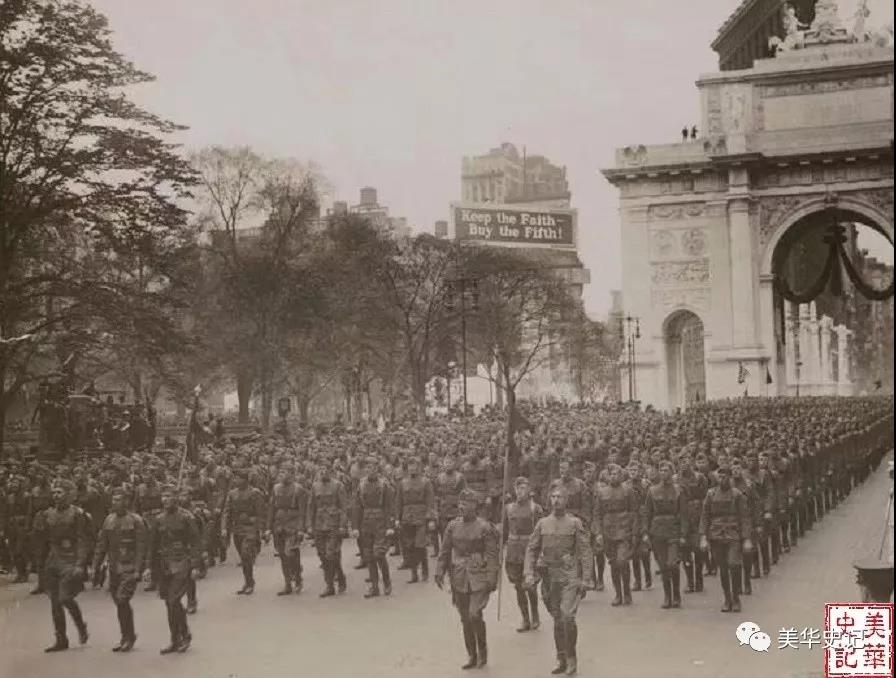

Picture 1: New York Victory Parade–second from right is Lau Sing Kee. Source: New York Archives

On May 6, 1919, the 77th Infantry Division of the US Army, led by General Pershing, passed through the majestic Arc de Triomphe and strode along the famous Fifth Avenue. The people of New York lined the streets, cheering and shaking the ground with celebration.

After the First World War officially ended in 1919, major cities in Europe and the United States held grand victory parades one after another.

In order to warmly welcome the triumphant soldiers, the Mayor of New York established a special committee to build a beautiful arch to celebrate the victory of World War I. The Arc de Triomphe is located at the junction of Fifth Avenue and 24th Street in Manhattan.

Figure 2. On May 6, 1919, At the New York Victory Parade, a triumphal arch was built to celebrate the victory in World War I. Source: New York Archives

On May 6, 1919, during a celebration ceremony held in New York City, the renowned General Pershing led a team on horseback at the forefront of the parade. When the First World War broke out, Pershing, who graduated from West Point Military Academy, was appointed as the commander of the American Expeditionary Force. He organized and commanded the training and operations of the American army on the French front.

So what is the story of the handsome sergeant in this photo?

Lau Sing Kee was born in Saratoga, California in 1896. His parents were from Shunde, Guangdong in 1990.

As a child, Lau Sing Kee moved with his parents to the busy and noisy Chinatown on the outskirts of San Jose. His father opened a shop selling cigars and sweets, and also worked part-time as a Chinese labor contractor.

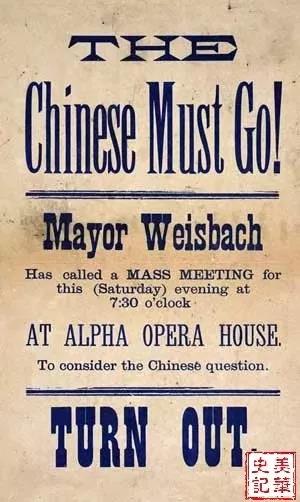

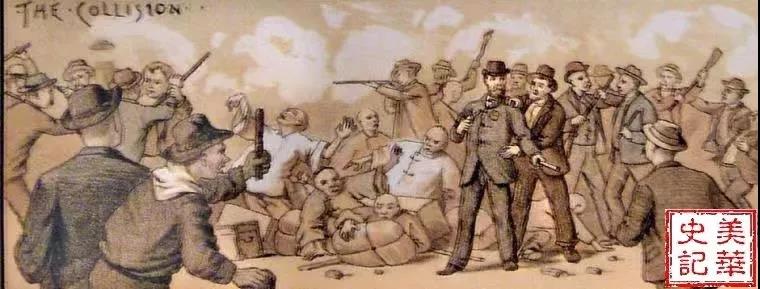

At the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act, American law prohibited Chinese workers from entering the United States, required Chinese Americans already in the United States to carry a photo ID with them at all times, prohibited Chinese children from entering public schools, and prohibited Chinese people from buying land.

The well-known slogan of anti-Chinese campaigners was “If the Chinese don’t go back, they can stay for the bullets.” So Chinatowns across the United States became a refuge for Chinese workers to escape persecution.

When Lau Sing Kee grew up, he moved from California to the Chinatown in New York to make a living. When the First World War broke out, Lau Sing Kee was enlisted to serve in New York City in 1917. At the time, most Chinese folks made a living by doing laundry, so Chinese people joining the army was a curious sight. Newspapers at the time said, “For the first time, Turks and Chinese join the army!,” and other newspapers said, “The army recruits in Chinatown.” All of the recruits were Chinese people born in the US. They were fluent in English, and they seemed to prefer to speak English rather than their mother tongue.

Lau Sing Kee served in the 77th Division of the US Expeditionary Force, No. 306 Infantry Regiment, and G Company. This division was called the “international division” because of the large number of first-generation immigrants that made up the troops, which included Greek and Russian immigrants. The highest commander was General Pershing, who was the head of many outstanding military endeavors. Lau Sing Kee’s unit was quickly transferred to the Western European Front.

Picture 7: US Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War I

It was August 14, 1918 when Lau Sing Kee’s troops were stationed in a village called Mt. Notre Dame in northern France. After the fighting began, the Germans started bombing with a strong offensive of 30 shells per minute, and at the same time released poisonous gas. At that time, there were a total of 20 communication soldiers in position. They were responsible for the communication between the troops, the command, and the front line. Lau Sing Kee was one of these 20 communication soldiers. Facing the attack launched by the German army, the communicators moved the attack forward in the face of machine guns, lethas gas and flamethrowers. The soldiers fell one by one. The fighting continued until the next afternoon. Some of the communicators were injured; some were unconscious or dead. Lau Sing Kee was poisoned. In 1919, Lau Sing Kee recalled in an interview with the San Jose Courier, “I felt like I was hit in the face by a pound of red pepper. My eyes, nose, and throat hurt so much that I couldn’t even breathe.” However, Lau Sing Kee resisted the pain and stood down the gunfire alone for three consecutive days and nights. The gunpowder was filled with smoke, and for at least 24 hours, he was alone in holding up the communication on the battle ground. Between the front line and the headquarters, Lau Sing Kee ran back and forth, about eight miles. Because of his efforts, the American troops were able to hold their ground. After Lau Sing Kee delivered the last message on the field, he collapsed on the ground. [4]

Picture 8: Sergeant Lau Sing Kee, Guardian of the Flag

Lau Sing Kee’s division finally succeeded in pushing back the German army to the opposite bank of the Vesle River in France.

Lau Sing Kee was promoted from Sergeant to Master Sergeant, and the famous General Pershing awarded Lau Sing Kee the Distinguished Service Cross, which was the army’s second highest honor. Lau Sing Kee was also awarded the Purple Heart Medal and the French Cross of Valor at the same time. He was the first Chinese-American to receive an American Battle Medal. The medal award speech read, “At the most critical moment, Lau Sing Kee demonstrated extraordinary heroism, immense courage, and dedication to his duties, putting personal safety out of his mind.”

Picture 9: General Pershing honors officers and soldiers of the expeditionary army.

Picture 10: Distinguished Service Cross awared to Lau Sing Kee

In addition to the army, the American media also strongly appreciated Lau Sing Kee’s humble and courageous character.

When a reporter from the Los Angeles Evening Herald asked him how he could stay on the battlefield for so long, he simply said, “No one was doing this at the time, only me. I had to.”

Another reporter asked him, “How did you do it when you stood alone? Lau Sing Kee simply replied, “I held on, that’s it.”

One month later, on June 13, 1919, in San Jose, California where Lau Sing Kee grew up, this son of immigrants was welcomed as an American hero.

Picture 11: On June 13, 1919, in San Jose, California, Lau Sing Kee and his parents accepted the cheers of the parade.

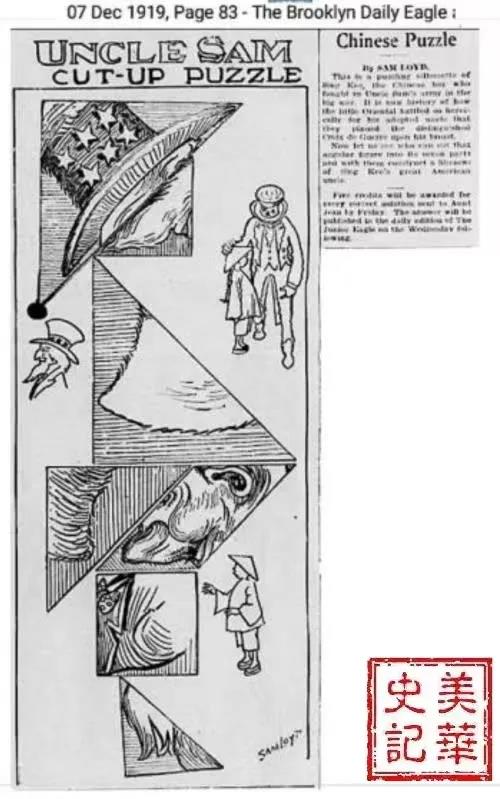

Lau Sing Kee was the first Chinese-American to receive the Distinguished Service Cross. Newspapers from the north and the south published the story of this Chinese-American hero. However, some people still treated Kee with racial discrimination. For example, the Brooklyn Eagle called him a “Chinese boy” and published a cartoon depicting him as a short child wearing a newsboy hat, with Uncle Sam stroking his head. The Los Angeles Evening Herald described him as a “quiet, law-abiding ‘China guy’ with a pair of small almond eyes.” [5]

After leaving the army, Lau Sing Kee was employed by the Immigration Bureau as an interpreter for ten years. Later, he resigned from the Immigration Bureau and opened a Chinese overseas travel agency in Mott St., Chinatown, New York, specializing in immigration and travel agencies. Lau Sing Kee’s office is located in this building:

In addition, Lau Sing Kee opened Chinese restaurants in Brooklyn and Staten Island. He also served as the civic leader of Chinatown. When the United States entered World War II, he served as a volunteer for the draft committee in Chinatown, and was also a liaison between the military and the Chinese recruits.

On June 3, 1967, Liu Cheng died of genetic disease at home at the age of 71. In 1997, 30 years after Lau Sing Kee’s death, his wife’s remains were buried in Arlington National Cemetery. [6]

Picture 14: Arlington National Cemetery. Lau Sing Kee’s tombstone and Lau Sing Kee’s wife’s tombstone.

However, in 1976, the ninth year after his death, Lau Sing Kee received a unique sort of praise. That is that the most famous American singer at the time Stevie Wonder composed a song titled “Black Man” which was broadcast all over the United States.

Picture 15: Steve Wonder, the most famous singer in the United States at the time

The song “Black Man” praises a series of American historical figures of different ethnicities. When mentioning the contribution of the Chinese, this song praised the Chinese Railway Workers and Bruce Lee, as well as Lau Sing Kee. The lyrics say, “Who was the soldier of Company G who won high honors for his courage and heroism in World War I?”

(Link to the song:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEoE2UQXduA)

Accompanied by the powerful singing of the “Black Man,” a new generation of immigrants emerged triumphantly from the hardships of Chinatown. Lau Sing Kee and his wife Ina Chan raised two sons and three daughters.

Lau Sing Kee’s eldest son Norman Sing Kee (Norman Sing Kee, 1927-2017) served in the US Navy during World War II. After the war, Norman Sing Kee completed his engineering studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While serving as a full-time engineer, he later enrolled in New York’s Fordham University. In 1955, he became the third initial practicing lawyer in New York’s Chinatown. [9]

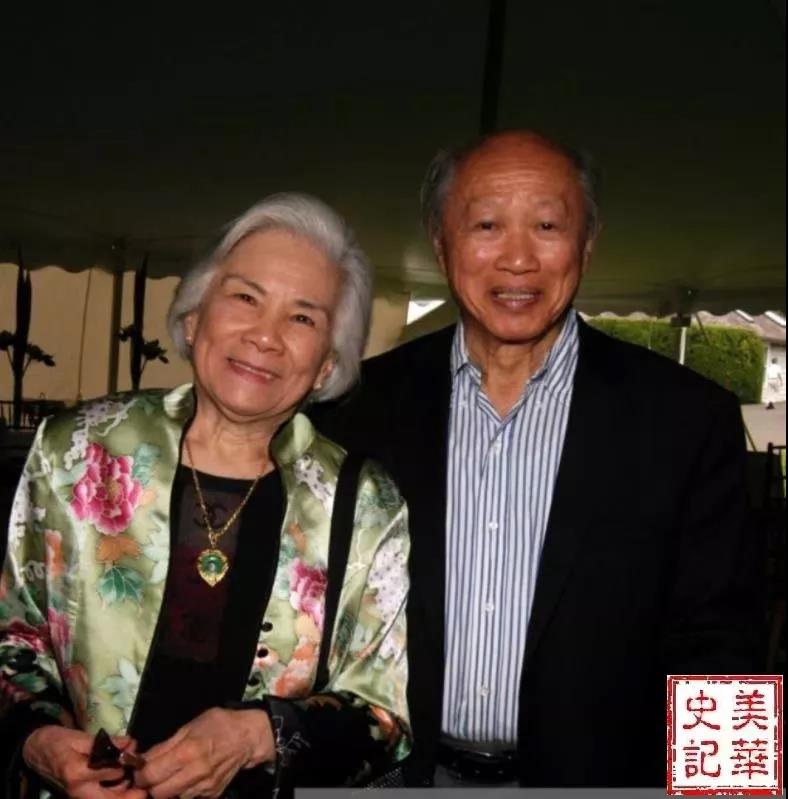

Picture 16: Norman Sing Kee, the eldest son of Lau Sing Kee, and his wife Esther Kee

In 1979, Norman Sing Kee and his wife Esther Kee were invited to the White House to attend a grand event hosted by President Carter to welcome Deng Xiaoping, Vice Premier of the State Council of China. In 1981, Norman Sing Kee organized a dinner in Chinatown and successfully invited US President Carter to the dinner. The couple was committed to promoting Sino-US relations. As early as 1979, Norman Sing Kee and his wife established the US-Asia Institute in Washington, D.C., dedicated to promoting the relationship between the United States and Asian countries. Norman Sing Kee also served as a member of the first US trade delegation to China. [8]

Picture 17: 1979 Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping visited the United States, President Carter held a welcome event at the White House

Norman Sing Kee stayed connected to his roots in the Chinese community. He not only participated in the establishment of the Chinese Policy Association, but also worked tirelessly to provide housing and public facilities for the people in Chinatown. [8]

Norman Sing Kee did not retire until he was 89 years old. In 60 years, he became a pioneer of legal services in New York’s Chinatown, and at the same time aided his community like a leader.

Lau Sing Kee’s second son, Herbert Sing Kee, (1930-2018), became an engineer after obtaining a master’s degree in engineering. However, after visiting a hospital in Haiti by chance, the 36-year-old Norman Sing Kee resolutely entered the Einstein College of Medicine in New York City to study medicine. The name of this hospital is Schweitzer Hospital, and its founder was Dr. Schweitzer (Albert Schweitzer, 1875-1965), a famous German doctor who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. [7] Dr. Schweitzer cared immensely for his fellow humans’ lives, and his deeds of saving the dead and healing the wounded inspired this young engineer. Norman Sing Kee finally graduated from medical school at the age of 40. He practiced medicine in Chinatown for 25 years. In addition, Norman Sing Kee served as the regional leader of the 64th district of the New York State House of Representatives.

As early as 50 years ago, Norman Sing Kee and his wife, Virginia M. Kee, founded the Chinese-American Planning Council. As the earliest Chinese non-profit community organization in New York City, the Planning Council has been actively providing English teaching and childcare services to new immigrants for half a century. Today it has grown to be the largest non-profit organization serving the new immigrants of Chinese immigrants in the United States.

Picture 18: Lau Sing Kee’s second son Norman Sing Kee and his wife Liu Mao Shuqing

Liu Sing Kee’s grandson, Glenn Sing Kee, still works as a lawyer in Chinatown.

Attorney Liu Aiming served as the chairman of the New York State Bar Association from 2014 to 2015. He was the first Chinese person to hold this position. As the president of the New York State Bar Association, he often traveled around to perform official duties. However, in areas sparsely populated with ethnic minorities, many people were surprised to see that the New York State Bar Association chairman was a Chinese man.

As the fourth generation of Chinese immigrants, lawyer Liu Aiming contemplated. Looking back on his family history, he would remember the great contributions of the Chinese in this land of America. Attorney Liu Aiming was quite emotional: The New York Bar Association was established in 1876. At that time, a large number of Chinese folks had already spread across the vast western part of the United States to reclaim wasteland.

Picture 19: Lau Sing Kee’s grandson, Lawyer Liu Aiming (right) and his father, Lawyer Norman Sing Kee (left)

Lawyer Liu Aiming, the grandson of Lau Sing Kee, encouraged Chinese Americans to contribute their efforts in all walks of life. He said, “The more successful the previous generation of Chinese is, the broader the road is for the next generation.”

Lau Sing Kee 1896-1967

Conclusion

In 1919, or one century ago, the triumphant American hero Lau Sing Kee raised his flag and strode to the forefront of the victory parade. It was a moment of worldwide celebration, with cheering voices and beating drums. On New York’s magnificent Fifth Avenue, Lau Sing Kee was probably the only “yellow” man.

100 years later, the only yellow-skinned man was also standing on the stage of the US presidential election. He enthusiastically displayed his refreshing philosophy of governing the country and proclaimed the leadership of Chinese descent.

If Lau Sing Kee in 1919 was fortunate enough to see the development of his fellow Chinese, how would he feel?

Sources:

1. https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/12842

4. Buffalo Evening News (Buffalo, NY) 28 April 1919, page 3, col 3

5. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York) 7 Dec 1919 Page 83, col 3

7. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Schweitzer

8. “A Tribute to a Chinatown Icon”, Justice Peter Tom, The New York Law Journal 12/13/2017

9. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks January 19, 2018 https://www.congress.gov/115/crec/2018/01/19/CREC-2018-01-19-pt1-PgE78-4.pdf

Pingback: 美华史记