Author: Zhida Song-James

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

Mrs. Gue Gim Wah (1900 -1988) was a legendary Chinese immigrant who made Nevada her forever home. She was the only Chinese American woman who served as a Grand Marshal of the official Nevada Day celebration parade. As a young girl, her first experience on US soil was her five-day detainment on Angel Island. After her release, she lived in the crowded yet isolated Chinatown in San Francisco, married to a man who was twenty-eight years her senior, attended the first-grade of a public school at age eighteen, and lived and worked in the Prince-Castleton area, near the “wild” Nevada mining town of Pioche. Widowed at age thirty three, she decided to continue her life in this frontier town despite her family’s offer to bring her back to San Francisco. With her resolute faith, hard work, and unwavering determination, Mrs. Wah established herself as a faithful member of the Christian community, a business owner, a celebrity chef, and a friend to former President Hoover.

Wah’s story not only reflects the struggles, contributions and achievements of female Chinese immigrants of her generation, but also it reflects the acceptance and the support from her kind-hearted community. Gue Gim Wah made the Prince-Castleton area her home; she was and still is the pride of that community.

~~~

On October 31, 1980, Nevada, the Silver State, celebrated its 116th anniversary. The capital Carson City held a grand parade that day. According to state laws, the Grand Marshal on the first parade car must be an influential person who has made outstanding contributions to the state. That year, the Grand Marshal was a Chinese woman: Gue Gim “Missy” Wah from the Prince Mine in Lincoln County. The Lincoln newspaper proudly called her “Our Missy Wah–Queen of Nevada” [1]. Reno newspaper columnist Rollan Melton described her as a woman with a huge heart, great courage, and a charming life experience [2]. In the 116-year history of Nevada, Gue Gin Wah was the second woman, the first Asian, and the first Chinese-American to enjoy this honor [3].

Lincoln County is approximately 175 miles northeast of Las Vegas. The mountains are tall, the air is cold, the land is sparsely populated, with a population of 5,036 in 2015. According to the 2010 Census, the Asian population was only 0.7%. How did Gue Gin Wah arrive in this remote desert as an outsider, but come to make great contributions to the Silver State?

First Visit to Angel Island

Gue Gin Wah was born in Kaiping, a county in the Guangdong Province of China in 1900. Her father Ng Louie Der was already a successful businessman in San Francisco’s Chinatown at the time, and he ran his own hardware grocery store. Ng Louie Der was married when he came to the United States. Like most of the Chinese immigrating to the US at the time, he left his wife and children in the Chinese countryside, and went back to see his family when opportunity allowed. Gue Gin Wah lost her mother when she was eight years old. In the second half of the nineteenth century, a series of anti-Chinese laws were passed, and anti-Chinese sentiment and prejudice emerged and spread. There were more and more restrictions on Chinese travel, which made Ng Louie Der feel that visiting his family was getting more and more risky. In 1910, the Supreme Court ruled that wives and underage children of Chinese businessmen were allowed to enter the country[4], so he decided to take the opportunity to bring his family to the United States as soon as possible. Twelve-year-old Gue Gin Wah embarked on a trip from Hong Kong with her family. When they arrived in California, the first stop to greet them was Angel Island. As the immigration law only allowed immediate family members of the Chinese to enter the United States, some Chinese “paper sons” appeared. These immigrants had forged documents, claiming that they came to the United States to unite with their families . Because of this, immigration officials created specially strict procedures to determine the identity of each migrant. The first passenger called out from the ship was Gue Gin Wah, who didn’t understand a word of English. Immigration officials questioned her for two days through an interpreter, and her family was detained for five days on Angel Island. Finally, the immigration officer summoned her family to compare their appearances and confirm the validity of her statement. Fortunately, she and her brother looked like their father, and they were released ashore to San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Gue Gin Wah lived in San Francisco for four years, living upstairs in her father’s shop. Ng Louie Der believed that it was not necessary to learn English in Chinatown, so he sent his daughter to a private Chinese school, where she first met local-born Chinese children. The anti-Chinese movement was on the rise, and only the Christian Church provided assistance to new Chinese families by teaching them some necessary English and guiding them to familiarize themselves with the new environment. Participating in church activities became Gue Gin Wah’s first taste of the outside world. These experiences had a huge impact on her. From then on, Gue Gin Wah became a loyal and active member of the Anglican Church throughout her life.

Mining Town Bride

When Gue Gin Wah was fifteen years old, Tom Fook Wah came into her life. Tom was born in Marysville, 40 miles north of Sacramento, in 1871. His parents died when he was very young. His uncle and aunt who raised him once brought him to Kaiping, where he met Ng Louie Der. Tom used to cook for American families and learned to read and write English. As an adult, he worked on farms, and often moved around the mining areas of California, Nevada, and Arizona, hoping to find a stable job. He mostly made a living by being a chef. Around 1910, Anti-Chinese exclusion was becoming very serious in mines around Ely. Tom’s own small restaurant was forced to shut down. So he went to Goldfield in south-central Nevada to look for a job. While he was on the train, anti-Chinese miners blocked the car door, preventing him from getting off the train. When he became desperate, he came across a man from Salt Lake City, Utah who told him that a new Prince Consolidated Mining Company was established ten miles south of the town of Pioche in Lincoln County and was hiring chefs. Tom knew that a mine in this remote area must have a good cook to keep its workers, and he was confident in his cooking skills. He was proven correct. With the growth of the Prince Mine, miner population gradually increased, and the company provided food and lodging for single workers. Tom was hired to manage the dormitory and the adjacent restaurant, which was also a place of social gathering. Later, his leg was injured in an accident. During his recovery, his doctor advised him to find a wife. At the time, Tom, who was in his forties, didn’t plan to return to China to find a bride like other young men did. Instead, he thought of Gue Gin Wah who he met in San Francisco.[5]

Picture 1: Gue Gin Wah wearing Chinese clothing, reprinted from Nevada Women’s Historical Project, Gue Gim “Missy” Wah [20]

Though they live in the United States, the Der family still maintained Chinese traditions. For example, all husbands or fathers of the family had the final say for all family issues and women rarely had a voice. At first, Gue Gin Wah didn’t have much interest in this man who was 28 years older than her, but she still obeyed her father’s decision. She married Tom in January 1916 and packed up her life to move to Prince Mine. At first glance, compared with San Francisco’s Chinatown, all Pioche had was bare hills in the isolated desert. During its most prosperous period, the mines in the Pioche area used to employ Chinese miners, so there was a small Chinese population. But by 1920, of the 2,287 people in Lincoln County recorded in the US Census, only 18 were Chinese. One can imagine the challenges Gue Gin Wah faced in this unfamiliar environment.

The mine manager and his wife warmly welcomed Tom’s bride to Pioche. She mostly stayed at home for the first two years. Tom told the shy and reserved Gue Gin Wah that she must learn English in this new world and get out of the house once in a while. Morley Godby, the main shareholder of the mine, heard that she was eager to learn English but was afraid that people would laugh at her being too old, so he personally brought the school teachers to her home. He encouraged her to learn and arranged for her to go to school. The school she enrolled in had only one classroom, shared from the first to the eighth grade. The children were very curious about their new classmate, but were very enthusiastic to help her learn English. The teacher also specially designed projects about Asia. Students, parents, and friends all came to participate. She learned quickly and skipped grades, completing the first through the eighth grade within a few years. The experience of going to school played a major role in her integration into local society. At school, she wore similar clothes to the locals, and met two lifelong friends: Mary Thomas and Elizabeth Gemmill, daughters of Leonard Thomas, the executives of the metal company under Prince Mine. Her father later bought Prince Union Mining Company. When Gue Gin Wah was interviewed years later about her experiences, the interview was held at Elizabeth’s house [5].

From 1916 to 1927, the development of the mining industry fluctuated. After the end of World War I, military demand for metals diminished. However, the mining industry flourished once again in the early 1920s. A new mine was opened near Castleton, and in 1926 a new silver-lead ore was discovered at Prince Mine. Hiring more miners meant Tom would be busier and earning more money. Unfortunately, a fire in 1927 destroyed their house and also burned down the savings that Tom, who did not believe in the bank, hid in it. Gue Gin Wah recalled that Tom threw the money bag out, but a gust of wind swept the money back into the fire, and it was all turned into ashes. We had to start over again [7]. They almost lost all their belongings after the fire. Tom decided to return to China in hopes of collecting the money from his investment there and bringing the inherited property back to the United States.

Picture 2: The original miner’s kitchen and dining room of the Prince Mine. The stove used by Gue Gin Wah is still inside. Original by the author.

While Tom was busy rectifying financial issues, Gue Gin Wah was also busy continuing to improve herself. Specifically, she signed up for teacher training courses. The travel certificate the couple held allowed them to return to the United States within one year, but due to various accidents, they had to apply for a one-year extension. At this time, the United States implemented the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which did not allow Chinese spouses of American citizens to become citizens [8]. Tom was born in the United States, his application for the extension was approved, but Gue Gin Wah, who was still a foreigner, encountered difficulties. The couple had to hire a lawyer through her father. At the same time, Gue Gin Wah and Tom also received support from their community. Godby, the major shareholder of the company that encouraged her to go to school, wrote to the US consulate in Hong Kong, proving that Tom had worked under him for 15 to 20 years in hopes that it would allow Tom’s family to return to the United States. Nevertheless, when returning to the United States, the immigration officer still treated Gue Gin Wah as a complete foreigner, interrogating her for nearly three hours before letting her enter the country.

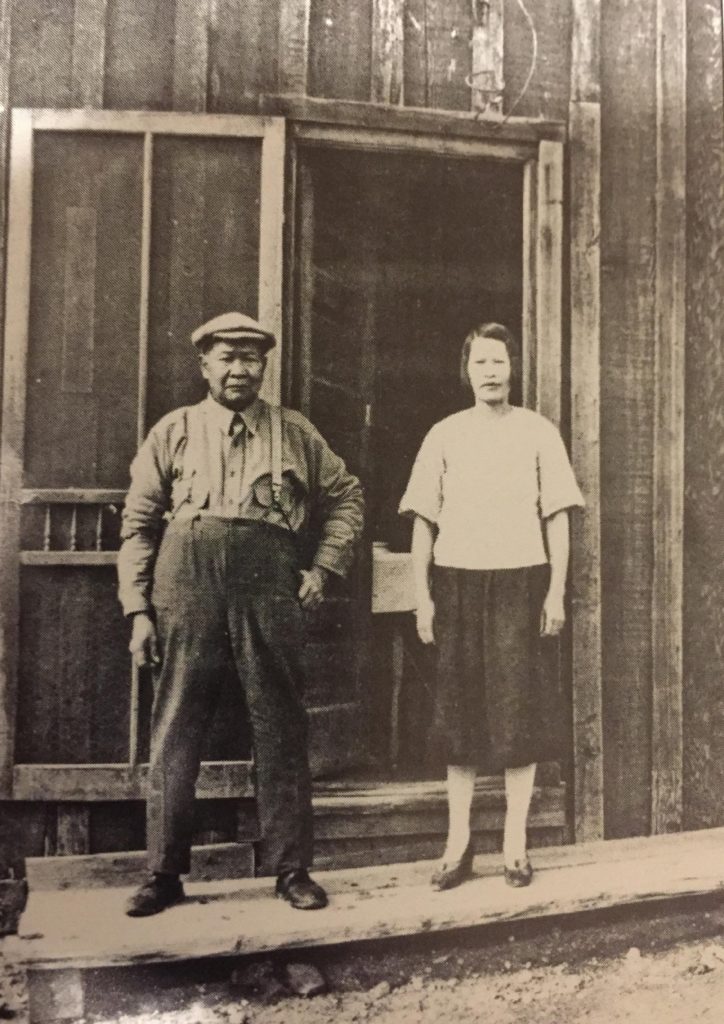

Picture 3: Tom and Gue Gin Wah in front of their home at the Prince Mine. Reprinted from Sue Fawn Chung with the Nevada State Museum: The Chinese in Nevada, Charleston, South Carolina: Acadia Publishing. 2011

During their stay in China, the couple adopted a two-year-old boy from a poor family. At the time, the adoption law in Nevada was relatively lax, allowing those of the “Mongolian race” to adopt children of the same race [9]. However, the federal government did not recognize the adoption as legal[10], and thus they could not bring their child back. Instead they were forced to leave the child with relatives in Hong Kong. For many years since, Gue Gin Wah tried every possible method, including writing to her Senator for help, but still failed to bring her adopted son to the United States. When Gue Gin Wah went to Hong Kong again in 1971, her adopted son had already married and established a business [11]. Gue Gin Wah had to give up this plan and instead brought her granddaughter Wei Ling back to the United States. After completing high school at Lincoln Middle School, Wei Ling attended Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah, and resided in San Francisco after marriage.

After returning to the United States, Gue Gin Wah temporarily stayed in San Francisco and found her first job in a garment factory. Tom planned to start over at the Prince Mine, so he returned there alone to arrange a place for his wife and himself. The Prince Mine he witnessed upon return was failing due to the recession. Tom decided to move to nearby Castleton, where the impact of recession was not so severe. He rented a house and brought Gue Gin Wah back. To make ends meet, Gue Gin Wah also had to work in the restaurant and the miner’s dormitory managed by Tom. Soon she became a chef. Sadly, such a stable life didn’t last long. In 1933, Tom’s injured leg deteriorated. Leonard Thomas led the community to raise funds to help them travel to San Francisco for treatment. Unfortunately, Tom died of cancer on August 17 of the same year. At the age of sixty-one, his body was returned to China for burial. The newly-widowed Gue Gin Wah declined to stay in San Francisco with her family. She returned to the Prince Mine alone [12].

Strong-willed Business Owner

The development of Nevada’s mining industry progressed smoothly in those few years. Lincoln County was one of the main zinc, lead and silver producers in the state. Due to China’s important position in the international silver market, Nevada Senator Key Pittman visited China. Under his promotion and influence, Nevada generally adopted a more friendly attitude towards China and Chinese people [13]. Gue Gin Wah’s friends helped her settle down again. Thomas let her live in the guesthouse of the Prince Mine and gave her a temporary job. Although her family in San Francisco wanted her to move back, Gue Gin Wah decided to stay in the Prince Mine.

The completion of the Hoover Dam provided reliable energy to the mining industry and brought a new era of prosperity. Soon after, the war in Europe was raging, and the US government had to step up mining and production of ordnance in preparation for the Second World War. Faced with the shortage of manpower in the mining industry, the government announced that people with mining experience willing to work in the mine could be exempted from military service. Consequently, a large number of people poured into the mining area. The work of chef Gue Gin Wah became doubly busy. She originally only worked in the Prince Mine. When the chef at the Castleton Mine suddenly resigned and left, she had to take over the cooking there. The government paid to build many houses in Castleton, and she rented one of them at a very low price and opened a restaurant. It was not easy for a single woman to run a restaurant, and Thomas once again provided valuable help. Whenever it snowed, he sent miners over to clean up the surrounding area to ensure that the restaurant could open on time. Gue Gin Wah worked tirelessly. The miners worked continuously in three shifts. She provided two shifts of hot food and one shift of packed lunches. She often slept in the restaurant when she was too tired. When the mine owner of Castleton found out, he built a small house next to the restaurant for her so that she would not have to go back and forth between her home at the Prince Mine and Castleton every day.

Gue Gin Wah became an American citizen during World War II. She learned to drive, joined the Pioche Professional Women’s Chamber of Commerce, and went to Bakersfield to participate in national defense training to identify enemy aircrafts. Nevertheless, her complexion and appearance still caused her some troubles. There was a young man who mistakenly thought she was Japanese and took a gun to a restaurant to find her. She calmly explained that she was from China, and that China and the United States were fighting side by side in the face of a common enemy, and gently offered coffee and snacks to that person. Two engineers from the mine rushed to the restaurant after hearing the news and took away his gun.

Picture 4: Photo of Gue Gin Wah’s ID when she participated in national defense training in World War II, reprinted from Lincoln County Record, June 23, 1988

During the war years, food was rationed. The clever Gue Gin Wah and the assistant she finally recruited utilized limited materials not only to make American meals, but also to introduce Chinese food to the residents of the town. The locals believed that eating delicious Chinese food made by her was a high-class delight. Former President Herbert Hoover was one of the mine owners of the Castleton Mine. He admired Gue Gin Wah’s cooking skills very much. He always went to her restaurant whenever he visited the area. He also told the miners that they ate the most delicious food in the area [14]. In Gue Gin Wah’s memory, Hoover was a very kind and warm person. He liked to chat with Gue Gin Wah, talk about his work experience in China from 1898 to 1901, his plan to translate Chinese mining regulations, and he especially liked to talk about improving the design of the light bulb. When the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library opened in West Branch, Iowa in the 1960s, Gue Gin Wah was one of the invited guests.

Widowhood, depression, and subsequent wars caused innumerable hardships for Gue Gin Wah, but it became a turning point in her life. Her tenacity, hard work, and capability shaped her into an indispensable member of the mining community. The Thomas family and other friends also played a very important role in her life. Later when she was the Grand Marshal of the celebration parade, Mary Thomas sat beside her.

Picture 5: After World War II, Gue Gin Wah learned to drive- Lincoln County Historical Museum collection.

Ghost Town Celebrity Chef

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, single miners went home one after another, and only a few people still needed board and lodging. In 1957, the government began to allow large amounts of low-priced metals to be imported, which caused the rapid decline of the Castleton-Prince mining industry. In 1962, there were only about 50 people left in the entire area, and the prosperity of the restaurant also diminished. Gue Gin Wah needed new customers. At this time, the reputation of Wah’s Cafe spread beyond Lincoln County, attracting many people from all over southern Nevada to taste her delicious cooking, and some even come from Las Vegas, 175 miles away. The restaurant was far off from the road, and her supporters put up a street sign on the side of the road which read: Wah’s Cafe–This Way. A few years later, a strong wind blew the sign down, but Gue Gin Wah didn’t bother to replace it. Only familiar people knew how to get to the restaurant, which inadvertently increased the mystery of the restaurant. Gue Gin Wah cherished the reputation of her restaurant. She bought ingredients from Cedar City, Utah, Las Vegas, and Chinatown, San Francisco. She also grew vegetables and spices in her own garden. She often worked alone as a cook, waitress, and cleaner. Later, when she got older, she opened up only three days a week, and there was no menu. Guests needed to make reservations in advance [15].

The legend of this renowned restaurant in a ghost town spread far and wide, and Gue Gin Wah’s story was published in the Salt Lake City Tribune [16], Los Angeles Times [17], Nevada-True Western Magazine [18], Las Vegas Observer [19], etc. Professor Sue Fawn Chung (1980, 1984) of the Department of History at the University of Nevada (UNLV), the Lincoln County Oral History Project (1981), and journalist Elizabeth Patrick (1982) of the Las Vegas Observer conducted several in-depth interviews with her to record her life experience in detail. In 1985 she finally decided to retire. Gue Gin Wah died in her Prince home on June 15, 1988 and was buried in the nearby Pioche Cemetery. Nevada Public Television (PBS) produced a program about her, naming her to be one of the people who shaped the history of Nevada [20].

Picture 6: Status of the Oji Mine (January 2018), author’s original photo

People Pass; History Remains

Gue Gin Wah had the opportunity to return to Chinatown in San Francisco many times, but she chose to spend her life in the mining town far away from the rest of Chinese society. She realized her value there. The few Chinese women who lived in the remote western regions of the US pioneered and paved the way to integrate with the local society; at the same time, they were also the ambassadors of Chinese culture. Gue Gin Wah’s restaurant was a combination of the American West and the Chinese East. Her kind of integration was not one-way, either. Her community not only accepted her, but also provided support and protection to her. When the author visited Lincoln County in 2018, the Prince Mine had ceased production and there were only eleven houses left in the town, but “Missy Wah” was still a well-known name. The staff of the County History Museum, the bartender of the Pioche hotel bar, and the young security guard of the Prince Mine each told the author a story about “our Missy Wah .” What people there remember is the extraordinary courage of a young woman from a distant country. With her wisdom, her hard work, and her strength, she lived a rich and colorful life, filled with ups and downs. What they remembered was her infectious laughter, and her unwavering perseverance. She deserves to be the glory of Lincoln County and the treasure of Nevada.

Sources:

- Lincoln County Record, November 6, 1980

- Reno Evening Gazette, October 29, 1980

- Sue Fawn Chung. “Gue Gim Wah: Pioneering Chinese American Woman of Nevada.” In History and Humanities: Essays in Honor of Wilbur S. Shepperson. Francis X. Hartigan ed. Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1989 pp 45-89

- United States vs. Mrs. Cum Lim, 176 U.S. 459 (1900)

- Sue Fawn Chung, 52, 59

- An Oral History Conducted and Edited by Robert D. McCracken, Lincoln County Town History Project, Lincoln County, Nevada, 1981

- Sue Fawn Chung, 69

- Department of State, Office of Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

- Nevada Statutes, 1921 Chapter 91, Section 1

- U.S. Government, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1906, Vol. 1 and 1914

- Lincoln County Record, November 18, 1971

- Sue Fawn Chung, 66

- Arthur Sewall: “Key Pittman and the Quest for China Market, 1933-1940”, Pacific Historical Review 44, no 3, August 1975, p351-71

- Interview with Mrs. Wah, Lincoln County Record, September 17, 1980

- Sue Fawn Chung, 71

- Salt Lake Tribune, May 7, 1961

- Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1972

- Nevadan: The Magazine of Real West, May/June, 1980

- Elizabeth Patrick: “Missy Wah of Prince: American from China.” in The Nevadan. Las Vegas Review-Journal, March 7, 1982.

- Nevada Women’s Historical Project, Gue Gim “Missy” Wah http://www.nevadawomen.org/research-center/biographies-alphabetical/gue-gim-missy-wah/

The iconic Missy Wah! Independent, smart, and hard-working.