Author: Zhida Song-James

Editor: Fan Jiao

When it comes to Alaska, what do you immediately think about? – Remote frontiers, cruise stops, the 49th State, spectacular glaciers, the highest peaks of the North American continent, the splendid Northern Lights, and perhaps Jack London’s White Fang and the dog sled race. What do you know about the history of Chinese Americans in Alaska – their lives, their stories, and their contributions?

Wherever you go on a cruise ship to this land today, it was the places where they sweated and the places where they were banned and evicted. Let’s go and look for the historical footprints of Alaskan Chinese, starting with the Gold Rush era.

Who is China Joe?

A Chinese in southeastern Alaska known as “China Joe” lived during the gold rush in the second half of the 19th century. Gold miners who lived in the uninhabited, snowy, rugged land took “everyone for oneself” as their motto. The kind-hearted “China Joe” refused to live by this motto. Instead, he saved many miners on the verge of despair and hunger. When approching the end of his long life, he had a reputation of “the only person in Alaska without enemies.”

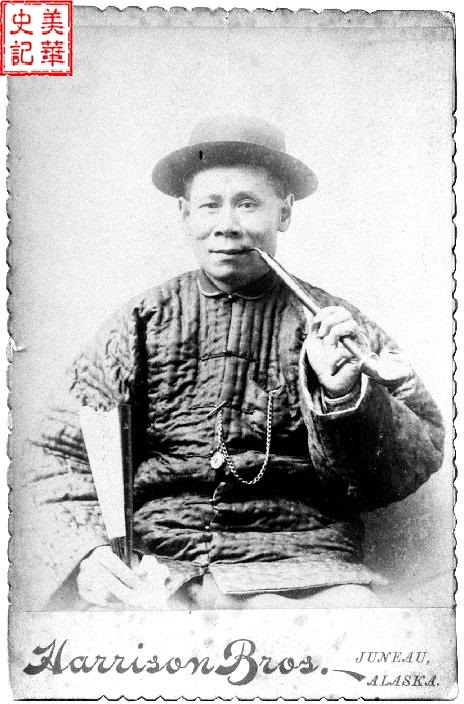

Figure 1. China Joe,Alaska State Library-Historical Collections

There are several versions of Joe’s original Chinese name. One theory is that Lee Hing, who came to San Francisco at 18, was a railroad worker. After completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, while most released Chinese workers stayed in California suffering various discrimination, China Joe headed north, looking for better opportunities. Finally, he bought a ticket to Alaska with the savings from his railroad income. (1)

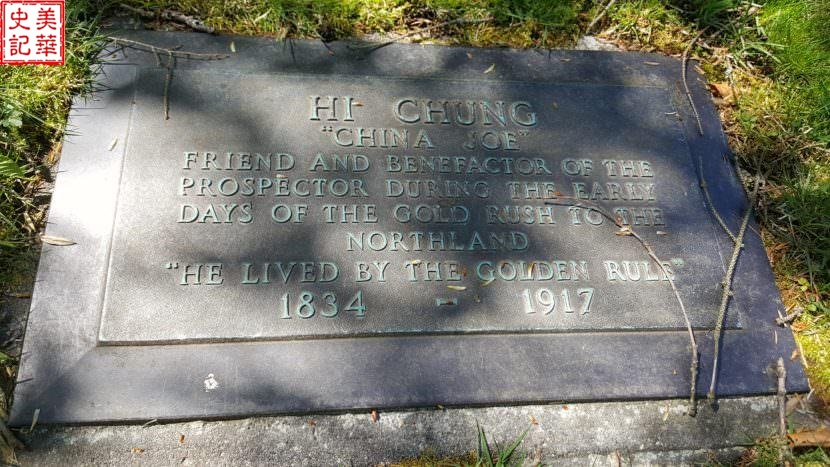

The other version is that his real name was Chew Ching Thui, born in 1834 in Guangdong, China. He first landed in British Columbia, Canada, in 1864. (2) Later, he moved to Boise, Idaho, where he learned baking. Later, he came to the Cassiar area and ran a bakery in Deasia Lake. (3) In his tombstone, his name was Hi Chung. (4)

Banned from the Yukon

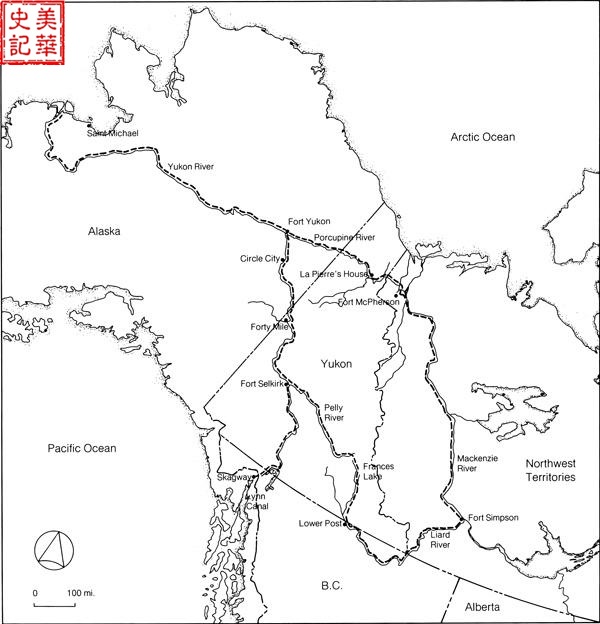

In the second half of the 19th century, prospectors moved to the Northwest along the Pacific coast. Believed there was gold in the far Northwest, hopeful prospectors showed up in the Alaskan Coastal Passage, looking for ways to get into the interior. Later, with the help of the local Chilkat tribe, a five-member U.S. Army squad led by Lt. Frederick Schwarka opened a passage from Dyea by the sea to cross the coastal mountains and further along Chilkoot Trail into the Yukon River basin. The Yukon River originated in Canada, first northward and west through Alaska, into the Arctic Ocean. From then on, prospectors from all over the world with the dream of making a fortune entered the vast Yukon River basin through the Chilkoot Trail. Canadian authorities have maintained population records for Yukon River Basin settlements. At the end of the 19th century, 260 prospectors were around Forty Mile, a major mining center of Upper Yukon. Most prospectors were Americans and Canadians, and there were also a few Nordic Scandinavians and Britons; there were also an Arab, three Armenians, a Greek, and a Chilean. “Yet the miners were definitely racist: when a group of Chinese and Japanese miners landed at Dyea, the miners had a meeting and voted to bar them from the Yukon.” (5) Here, we observed that the democratic process led to a racially based decision. The Chinese miners who endured untold hardship coming to the north could not get into the inland; they must find a way to survive on the narrow coast.

Figure 2. 19th Century Yukon River Basin and Routes (Map by S. Epps.) Parks Canada http://parkscanadahistory.com/series/chs/19/chs19-1e.htm

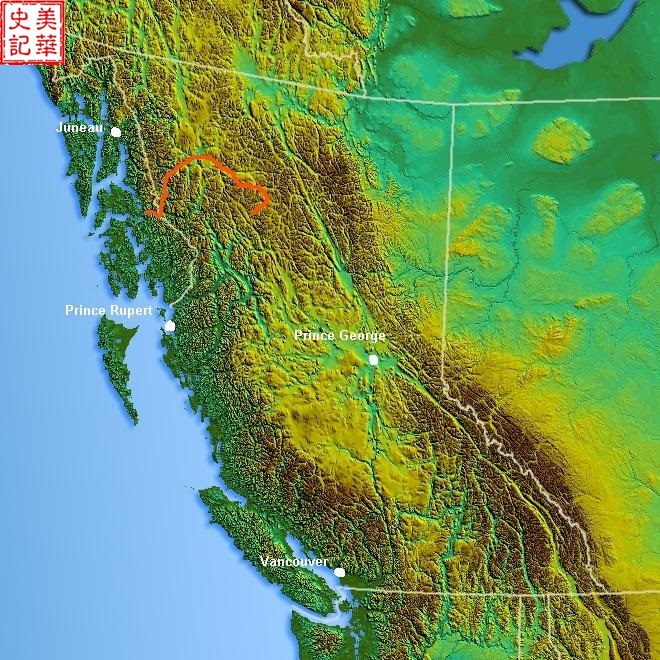

Figure 3. Stikine River, flowing from British Colombia, Canada to Coastal Alaska

Stikine River (red in Figure 3) is located in southeastern Alaska. In 1868, the United States built a military outpost, Fort Wrangell, near the river’s mouth. However, there were no permanent residents until 1877. Wrangell town eventually developed through several gold rushes in 1861, 1874, 1877, and 1897. During the periods, merchants built casinos, salons, and bars to profit from the prospectors. Thousands of gold miners entered Cassiar District along the Stikine River in 1874 and further to Klondike in 1897.

Snowy Winter Rescuer

After arrived Fort Wrangell, Joe bought a cabin and soon opened a diner. News of this new diner quickly spread among miners and mountain men. It was these dinners who gave the owner nickname China Joe. More and more people heard about the place, and some friends encouraged Joe to open a lodge so that miners could have a comfortable place to rest in winter when they couldn’t work in the mountains. Joe thought it was a good idea, but he didn’t have much money to build a new house. Instead, he bought a ship Hope, abandoned in Wrangell Harbor and, with the help of his miner friends, pulled it to the beach and turned it into a diner-and-lodge. Joe insisted on treating all tenants equally, no matter how much money they had in their pockets. Some miners who spent the winter there signed a $500 IOY before heading to the mountains in spring, promising to pay it off when they find gold. Joe gave them a good luck wish and told them he could wait until they had money to repay. Most indeed kept their promises and settled their accounts as soon as they found gold.

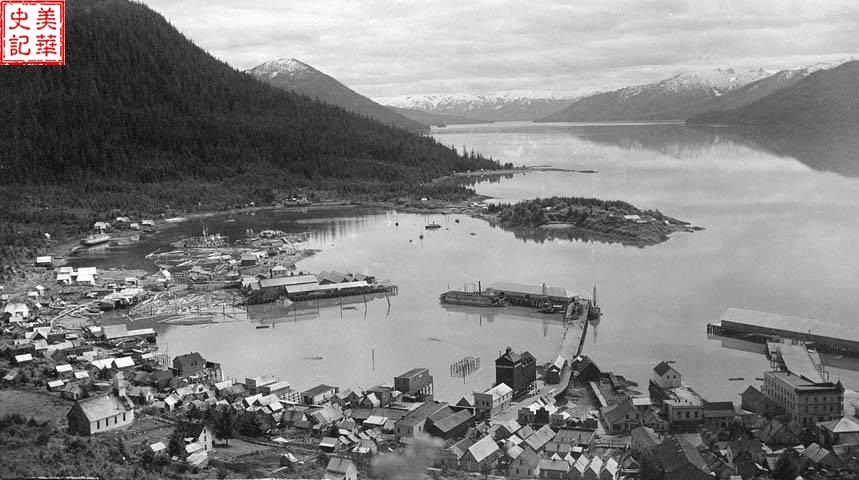

Figure 4. Wrangell, Alaska in 1897

Seeking gold along a river is as much a matter of luck as experience. The practice then was that prospectors select and stake a parcel of land to declare their mining rights. They must register their rights within the given time limit. After it, the registrant owned the gold he mined from the stake. However, gold deposits may vary between banks of the same river, even in adjacent parcels.

In 1872 the first batch of gold was discovered at Cassiar District on the upper reaches of the Stikine River. Some of the first miners were friends of Joe. In return for Joe’s past goodwill and trust, they registered some parcels under the name of China Joe and asked Joe to join them. Upon receiving the message, Joe went up to the mountains, bringing abundant winter supplies, and planned to stay in the gold camp for an extended period to serve his friends.

All the supplies must arrive at mining camps before the first snowfall. Goods were first shipped to the upper reaches of the Stikine River by a boat, then along the mountain road to the camps. For miners receiving the supplies on time was their lifeline. The weather was bitter in the winter of 1872-73. When the upper Stikine River unexpectedly froze several weeks earlier, all the shipments stopped. The deep snow buried rugged trails, none of the supplies arrived. Isolated in their gold camp, miners realized that this winter would be very harsh and starvation seemed inevitable. Although everyone had some gold, these little yellow rocks were useless to trade to buy anything. Words of Joe had brought a lot of supplies quickly spread among miners.

Two swindlers came to Joe to force him to sell his food to them, intending to resell it to the hungry miners for a profit. Joe refused, and the two raised their offer repeatedly but were received firmly and politely rejection time and time. Finally, they threatened to kill China Joe. Joe’s friends overheard their threat. The two crooks suddenly found themselves facing the muzzles and heard an order to leave. They had nowhere to go until spring, only nervously remained in the camp with others. Joe knew that the lives of other miners were in his hands during this bitterly cold winter. He could have asked them to trade all their gold for food to make himself rich overnight. Instead, Joe gathered the miners and distributed his lour, coffee, tea, and sugar equally to everyone. The two men who threatened him also received their share. As for the return, Joe just asked everyone to wait for spring supplies and return the same amount of food to him. With his help, miners all survived the winter.

The gold deposits were not abundant. Joe returned to Wrangell to continue running his business, later moved to Sitka. No matter where he lived, he had always been the same as before, never capitalized on the difficulties of others.

Gold was discovered near Juneau in 1881. Joe moved to Juneau, bought a small lot on the corner of Main Street and Third Street, and opened Juneau’s very first bakery. Year after year, China Joe kept helping many hungry miners and never asked for recognition or reward. Yet his goodwill did not always lead to a fair return.

Figure 5. Gold mining boat near Dawson City, Yukon, photographed by Zhida Song-James.

Dangerous Time of Chinese Exclusion

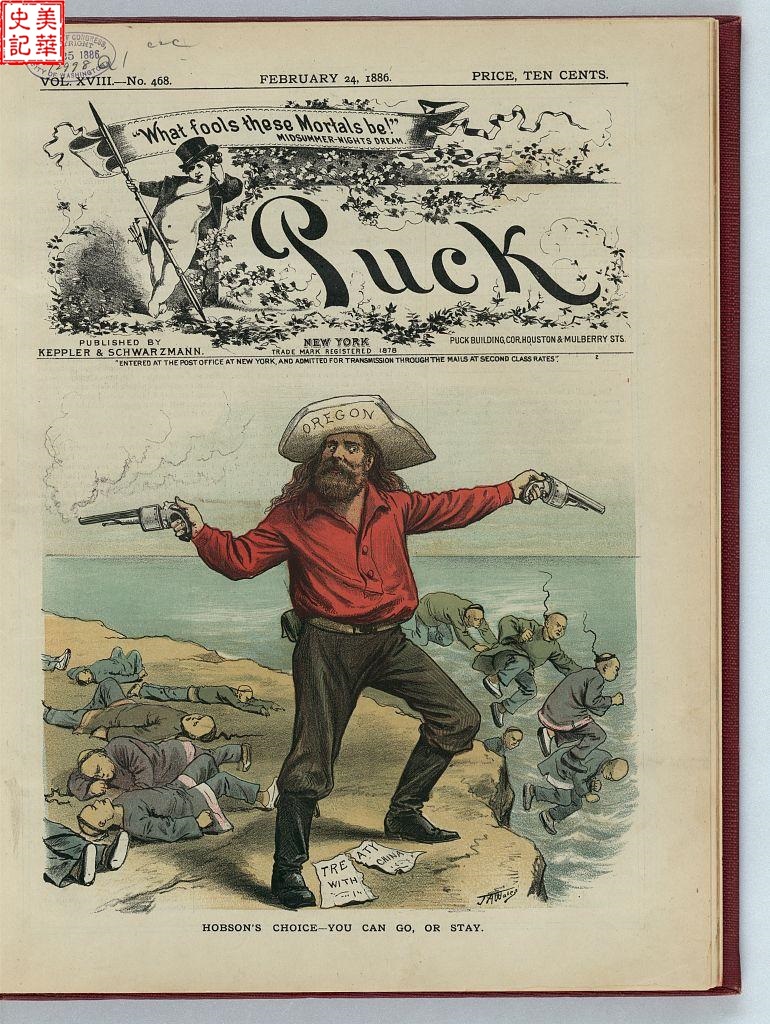

The U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. In the following years, waves of expelling Chinese swept across the country, including remote Alaska.

Figure 6. Stay or Go, Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann, February 24, 1886

Gold mining in Alaska gradually industrialized from placer to lode mining. Waged laborers replaced individual prospectors. In 1884, the Treadwell gold mine on Douglas Island, just across a channel from Juno, hired a group of Chinese workers from San Francisco. Their lower wages caused a strong reaction among white workers who complained that these immigrants were taking away their jobs; therefore, all Chinese workers must be evicted. On a winter morning, an explosion occurred in the Chinese workers’ housing area. Awakened people found that the blast destroyed a house and several nearby shops. Fortunately, no one was injured. By the next day, angry residents raised five hundred dollars to offer a reward for catching the criminal and bringing him to justice. Later, they increased the prize to $1,400, but the criminal had never been arrested.

Figure 7 Treadwell Mine,1890

On August 6, 1986, more than a hundred armed men came to Treadwell mine and ordered the Chinese workers to leave, threatening them with “unmistakable language with death if they remained. “… the Chinaman expressed a readiness to stay and fight, but being unarmed, and a general massacre being almost certain to follow any resistance on their part, it was reluctantly admitted that only thing for them to do was to leave.” (6) Eyewitnesses said they were packed into two schooners, not given anything to shelter from the inclement weather. All they had was some rice which was barely enough to keep them starving to death on board. There are more than 150 miles from Juneau to Wrangell, Chinese workers were drifting at sea dangerously. Fortunately, a passing steamship, Ancon, rescued the Chinese workers and returned them to Juneau. Chinese workers had to borrow money to return to San Francisco.

An Engineer, Mr. J.B. Hammond, witnessed the violent expulsion. He told New York Times that it was the most cowardly and inhuman action. “The Chinaman were not to blame for being there, having gone to work under a contract made in San Francisco at a time when it was impossible to get white labor to go to Alaska.” He said. The Mine owners would have to pay indemnity to the Chinese, and the owners could demand indemnity from the Government. Many famous people who happened to be in Alaska spoke out and strongly condemned such actions; among them were Ex-Governor Hoadley of Ohio, Bishop Warren of Colorado, Dr. Haven of Chicago, and Chief Justice Waite. They said it was inhuman and barbaric to compel the legally hired Chinese workers to quit their jobs, forcing these defenseless people in unseaworthy boats for a dangerous journey down the coast. (7). However, at the time, no one thought it was an act of racial discrimination.

One can’t help but ask: What about Joe? Was he safe? Before the two schooners left, someone shouted that “there was a Chinese left. ” The thugs barked to catch “China Joe” and to put him on the departing boat.

Joe’s friends heard about it, acted immediately. When the mobs rushed to Joe’s bakery, a rope had been pulled up on the road, a man stood on a stump behind, telling listeners how many lives had been saved by “China Joe,” this generous and kind Chinese baker. Supporters with guns appeared from all sides. When the speech was over, the mob heard the sound of pulling the shot bolts. They retreated without a word. However, this was a dark day of racism in the history of Juneau. All Chinese were driven out but Joe. Since then, he became the only Chinese who remained.

Only Friends without Enemies

Joe, who lived alone, was still active in the community. During the holidays, he opened the bakery door, set up food, and invited everyone to come to celebrate together. Joe’s bakery was on Juneau’s central street. Before the electricity reached Juneau, he often lit candles at windows at night for passers-by. Locals call it “China Joe’s Lighthouse.” (8) Even with the arrival of electricity, Joe still lit the candles in his window. The small candle lights delivered his care and warmth to the hearts of those passing by. Joe often gave cookies to children who came to the bakery. Year after year, Joe’s kindness, generosity, and thoughtfulness continued to touch those around him.

Joe had lived in Juneau for 36 years, made many friends throughout his life, and became a prominent figure in the community. His contemporaries gradually faded away; he was a pallbearer at almost every funeral requested by the families. In 1889, Joe Juneau, one of the founders of the City of Juneau, was terminally ill in Dawson. He made his final wish clear that he would like to have his body return to Juneau and Joe to be one of his pallbearers at his funeral. On the evening of May 18, 1917, China Joe, respected and beloved by citizens in Juneau, died of a heart attack at 83.

Locals said that Joe had long been a rich man. If he wanted, he could have returned to his home in China, peacefully enjoyed the fruits of his lifelong hardworking and goodwill. However, Joe stayed in Alaska, the last frontier of the United States, shared his kindness, and generously helped all those in need. He spent most of his life away from his native land, living in a place where hardly anyone spoke his language or understood his customs. Nevertheless, he made Juneau his home, where he became a well-respected citizen, and locals memorized him as “the only person in Alaska who has no enemies.”

The years pass by, but people haven’t forgotten Joe. In 1960, Charles Carter, the former mayor of Juneau, who had received cookies from Joe as a child, made a memorial plaque for Joe. Today, we can still see the relics of Joe in the State Museum of Alaska, including a photograph of Huqin, a Chinese musical instrument, and a photo of him when he became a member of the Alaska Pioneer Association in 1887 (see Figure 1). He is documented in the state library’s archives as “the favorite immigrant of the gold rush” (9). Mark Whitman, a local historian of Juneau, has collected information about Joe over the years and made it available to Alaska libraries, archives, and museums. His friend Brett Dillingham wrote a play about Joe. Whitman was so moved by Joe’s life stories, he often visited his grave on the anniversary of his death and cleaned his tombstone. “Joe used to clean friends’ graves. He would like someone to do that for him,” Whitman said. “Do what you would like others to do to you; that was the golden rule he lived by.”

Figure 8. China Joe’s tombstone at Evergreen Cemetery, Juneau, Photograph by Tripp J Crouse/ KTOO

In her recent book Space-Time Colonialism: Alaska’s Indigenous and Asian Entanglements, Juliana Hu Pegues wrote a chapter about China Joe, titled “The Virtual Story of the Last Edge: The Alaskan Gold Rush and the Legend of China’s Joe” (10). After outlining the life of China Joe and the relevant accounts of Juneau local history, she argues that Chinese Joe, which has been repeated extensively in the Alaskan media and popular history since the end of the 19th century, has become a folktale. Nevertheless, the story of China Joe contrasts sharply with the rustic and rough individualism common in Alaskan legend: contrary to the motto “Everyone for oneself,” China Joe’s actions are for everyone, highlighting his selflessness.

References

- LitSite Alaska | People of the North > Heroes and Scoundrels > Lee Hing, or “China Joe”

- I-Chun Che: Lonesome Land, Lonesome Land: | Hyphen Magazine May 1, 2005

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/China_Joe

- Tripp J Crouse:100 years after China Joe’s death, Juneau historian remembers immigrant May 16, 2017, KTOO https://www.ktoo.org/2017/05/16/100-years-after-china-joes-death-juneau-historian-remembers-immigrant-pioneers-protected/

- Archie Satterfield, Klondike Park from Seattle to Dawson City, Fulcrum Publishing, 1993. pp31

- The New York Times, August 24, 1896

- Ibid

- Lee Hing, or “China Joe”, http://www.litsitealaska.org/in

- China Joe and Other Foreign Miners. Alaska’s Gold. 1999. Alaska State Library http://library.state.ak.us/goldrush/STORIES/chinajoe.htm

- Juliana Hu Pegues: Space-Time Colonialism: Alaska’s Indigenous and Asian Entanglements, University of North Carolina Press, May 2021

China Joe and Chinese Miners during the Alaska Gold Rush

ABSTRACT

Alaska is viewed as a remote but exciting place as the last frontier. Hundreds and thousands of tourists visit its winding and misty coasts, magnificent mountains, and spectacular glaciers each summer. It also is a place with rich and unique histories. Alaskans are commonly recognized as more resilient, more adventurous people. Since the mid-nineteen century, prospectors edged northwards along the Pacific coast and appeared on the rivers flowing into the Insider Passage of Alaska. At this time, Chinese Americans began to move up to Alaska. However, when a group of Chinese and Japanese miners landed at Dyea, they were barred from entering the Yukon basin.

This article provides a glance at the lives of Chinese Americans in the Gold Rush era through the experiences of China Joe, a merchant, a miner, and a baker. His early life was closely tied with miners. He was one of the earliest settlers of Juneau, the Capital of Alaska. There he survived waves of the Chinese Exclusion movements, lived for thirty-six years, and became a prominent citizen of Juneau. By the time he died, he had the reputation of “the only man in Alaska without an enemy.”