Author: Zhida Song-James

Tara Nelson grew up on the coast of southeastern Alaska. She wrote an article in October 2017 about her hometown, where once was one among more than a hundred salmon cannery sites in Alaska (1). “It always felt like an epic childhood growing up in the post-apocalyptic ruins of the burned and abandoned cannery in remote Union Bay, Alaska.” She wrote. “We were cut off from the outside world, with only our family for companionship. But I never knew until recently that the old cannery where we grew up had a close connection to a famously pivotal moment in modern Chinese history. It’s a moment so famous it’s taught in Chinese colleges and has been documented in a film.”

The incident took place in Kunming, a city in southwestern China, less than a year after the long-lasting Second Sino-Japanese War. On the afternoon of July 11, 1946, a middle-aged couple got out of a bus at Qingyun Street, walking home after watching a movie. The man just went uphill and heard a sudden “bang” behind him and fell. The woman hurried to help, only found the man was shot in the back, blood straight. The injured were Li, Gongpu, a well-known Chinese social activist and one of the “Seven Gentlemen” who led the movement to unite the county fighting against the Japanese invasion in the 1930s. He died the next day at Yunnan University Hospital (2). Three days later, on July 15, his good friend Wen, Yiduo, an influential poet and a professor and of The National Southwest Associated University, delivered the famous “Last Speech” at a rally in memory of Li, Gongpu. Wen was assassinated that afternoon. The “Li-Wen’s Murder” shocked China at the time.

Tara and Li’s path intersects at a salmon cannery in Alaska. Visitors to Alaska often bring home delicious salmon. From the nets to the dining tables, tones of salmon were processed in canneries, large and small. It was Chinese workers who first labored in the salmon processing industry and turned the salmon from a local fare into gourmet food over the country and the world. Li, Gongpu was once one of those Chinese workers.

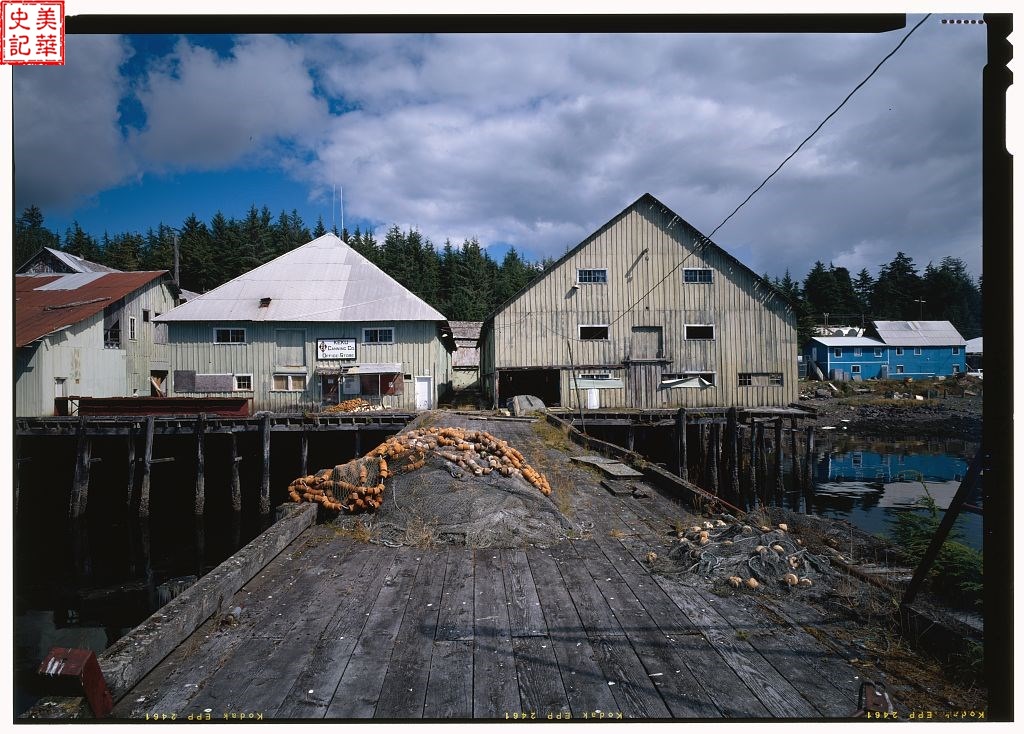

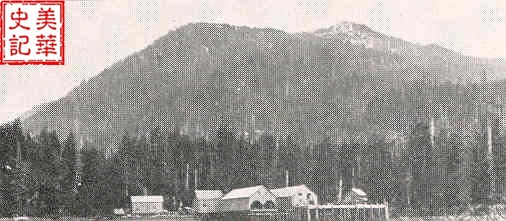

Figure 1 Relics of Union Bay Cannery where Li, Gongpu worked and Tara Neilson grownup. Photo by Tara Neilson.

Alaska Salmon Processing Industry

Alaska salmon processing industry started from a few workshops, where the fish were simply salted before being shipped out. These workshops gradually evolved into salmon processing plants with complete assembly lines as the salmon market expanded. Typically called canneries, these factories have their fishing fleets and process the freshly caught fish with their own packaging cans. Salmon were cleaned, cut, sorted, put into sealed cans, cooked, boxed until ready to be shipped away. The first canneries, owned by The North Pacific Trading and Packaging Co, opened in 1878 at Klawock and operated until 1929.

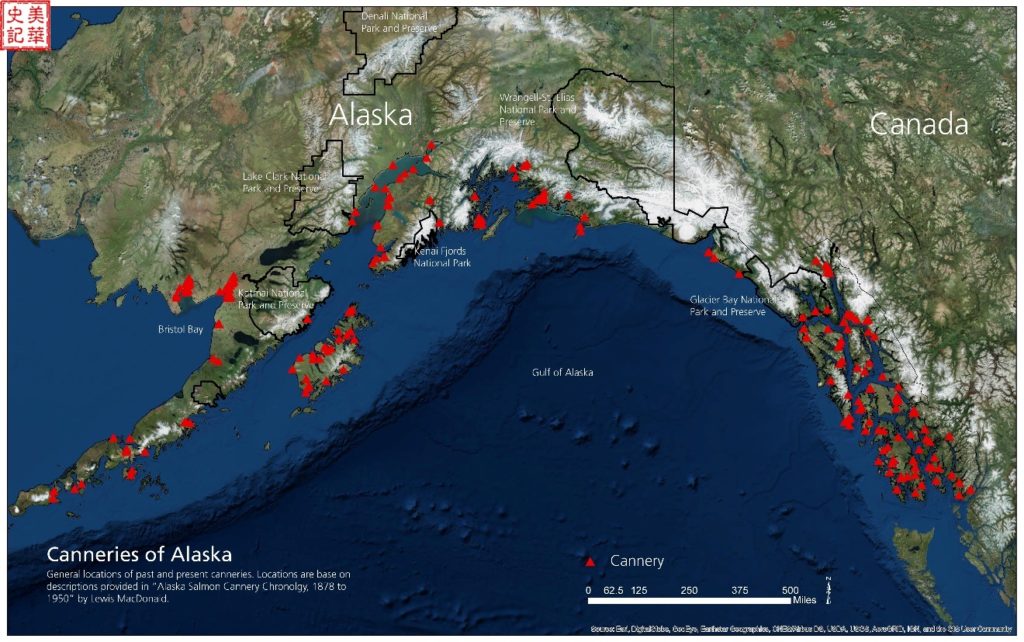

Salmon canneries scattered along the entire coast of Alaska, from the Southeast coast, bordering with Canada, extended to the Aleutian Islands, including the shores of Kodiak Island.

Figure 2 Canneries of Alaska Source: National Park Service

Alaskan salmon production peaked at 130 million in the mid-1930s. The total commercial catches declined significantly from the 1930s to the mid-1970s. Between 1878 and 1950, 134 salmon processing plants were built across the State; by the end of 1950, only 37 were still functioning. (3) Still, Alaska remains the world’s largest salmon producer. Salmon fishing and processing are seasonal. The canneries operated at their total capacity during the fishing season and employed many workers. Workers’ living quarters were typically near the factory building. Each cannery operated independently, and the living quarter became a self-sufficient village. In addition to ship docks, warehouses, and cannery buildings, these salmon villages included dormitories for workers, dining facilities, some single-family homes, shops, laundromats, clinics, and detention facilities. In large villages, there were also churches and cemeteries. During the high season, the dining halls were the village’s community center. Once the season was over, workers had left and houses empty; only a lone keeper stayed to guard facilities. The cannery silently remained on the shore, waiting for next year’s fishing season to come again.

Figure 3 The Kake Cannery near Kake, Alaska. National Park Service, nps.gov

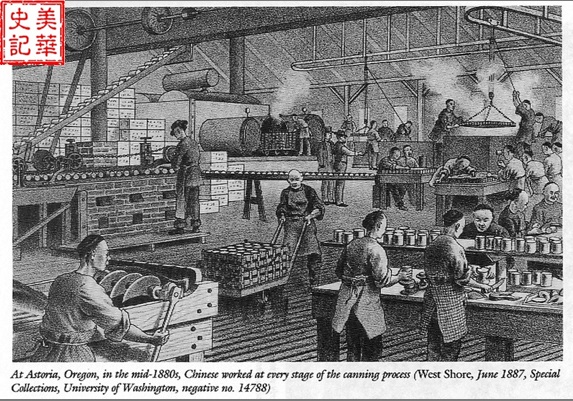

It was the Hume brothers who started salmon cannery in the U.S. America’s first salmon canning workshop opened in a barge on the Sacramento River, California, in 1864. Two years later, the Hume brothers moved their workshop to the Columbia River and started the commercial salmon processing industry, employing the first fifteen Chinese workers. By 1874, the majority of workers in all thirteen canneries on the Columbia River are Chinese, and some canneries with all Chinese only. In 1878, these workers began to come north from Washington state to Klawock and Sitka (4), becoming the pioneers in the Alaskan fish canning industry. Besides the First Transcontinental Railroad construction, salmon canning became the second industry dominated by Chinese workers, and the northwest United States became a new gathering place for Chinese workers.

Figure 4 Hume Label (1893)

Contractor Era

Why did this industry hire so many Chinese laborers, and how were owners able to reach out to these immigrates? Salmon canning is a seasonal but labor-intensive job. Workers must work long hours, sometimes even over ten hours daily during the peak period regardless of the day or night. Fish processing is messy, and workers must be willing to work in a wet, smelly, and untidy environment. They have to stay for the entire salmon season, and of course, the lower the wage, the better for owners. Cannery owners believed that Chinese workers were compliant, productive, and reliable, so they contacted Chinese labor contractors.

Chun Ching Hock (1844-1927) and Chin Gee Hee (1844-1929) were the two major contractors in the Seattle area. (5) Through the contracting system, cannery owners did not have to contact workers directly. They pay the contractor’s fees collectively according to the number of workers recruited. It was contractors who were responsible for recruiting workers, providing basic accommodation, hiring Chinese-speaking foremen to manage workers in canneries. They also settled payments with the workers at the end of a season. Due to their limited English skills, Chinese laborers were entirely under the control of the contractors and their Chinese foremen. They lived in large dorms with wooden beds, eating at dining halls with the food made by Chinese cooks hired by the contractors. An 1890 report recorded that the food provided by a contractor included salted eggs, tofu, bamboo shoots, sugar canes, and gingers. In addition, opium, gin, tobaccos, and Chinese wines were also made available. (6) Chinese laborers themselves also planted fresh vegetables as their supplement. Some historians believe that contractors profited plentifully from this process. (7) Some foremen took kickbacks from suppliers, deducted daily necessities, treated workers unequally, and retaliated against those who complained. But it is undeniable that such a contracting system helped the Hume Brothers hire many workers quickly and rapidly develop their business. Other cannery owners discovered that it was a viable model and promptly followed suit.

Figure 5

Seattle had become a hub for Chinese cannery workers by 1900. Every April, Chinese workers assembled here to sail north. They returned here at the end of the fishing season, typically at the end of August. On April 2, 1900, there were 150 Chinese workers aboard the steamboat George E. Starr to the Blaine cannery. Ten days later, the other steamboat, Ruth, carried 52 Chinese workers to the cannery in Icy Straits. (8) Passenger ships were often followed by a string of cargo ships carrying materials and other supplies. This season is spectacular on the Seattle coast. Portland and San Francisco are also important gathering sites and starting points for Chinese workers.

Figure 6 Balclutha, Formerly known as the Alaska Star, transports Chinese workers north from San Francisco to canneries in Alaska and canned salmon back. San Francisco Maritime National historical park

While fishing and processing are two closely linked steps, they were carried out separately by two non-connected populations. Europeans, especially Italians, operated fishing boats but were hardly seen in canneries. Fish processing was often believed as female work. Cutting, canning, sealing, and testing were all done manually. Chinese workers mastered the process; they were swift, nimble, and agile, not afraid of dirty and messy. Most importantly, they were paid lower wages. Canneries wanted to keep such workforces as long as they could. Even at the height waves of the Chinese expelling after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, there were no such activities against Chinese cannery laborers on the far Alaska coasts.

However, while the salmon canning industry continuously expands, the Chinese labor force sharply declines after the Chinese Exclusion Act. The door for Chinese immigrates was closed, and canneries could no longer hire younger workers to replace the aged ones. Two changes emerged in the industry: the machinery was introduced to replace manual works, with a single machine replacing up to 30 workers, and Japanese immigrants replaced Chinese laborers. The early Japanese laborers were still managed by Chinese contractors, who eventually gave way to Japanese contractors and managers as the growing number of Japanese immigrants joined the workforce in canneries.

The Emergency Quota Act, passed by Congress in 1921, first capped the number of immigrants entering the United States. In 1921 the total number was 350,000, which reduced to 165,000 in 1924. (9) Furthermore, the Immigration Act of 1924 established the nationality quota, i.e., the number of visas granted to immigrants for any nationality could only be 2% of the total population of this nationality living in the U.S. by the 1890 census. Although the original intention was to restrict immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, these quotas effectively excluded Asian immigrants from entering the U.S. (10)

Since then, Pilipino workers have replaced the Japanese. The Philippines became a U.S. territory after the 1898 Spanish-American War, so Filipino workers came to the U.S. without quotas. They quickly became the main working force of the canneries, and more and more Alaskan natives also joined. Starting with hard-working Chinese, the immigrants and natives together made the salmon processing from small workshops into a booming industry. Hundreds and thousands of canned salmon were delivered to the dinner tables of American families and exported around the world, even as an integral part of the American military’s rations during World War II.

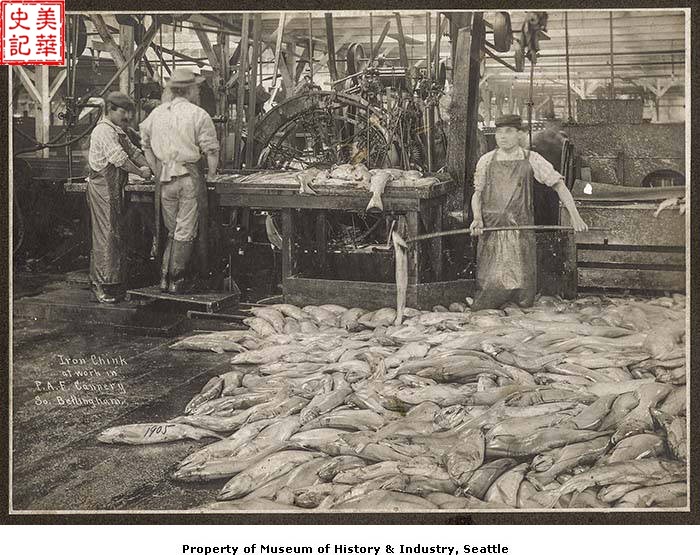

Figure 7 Salmon processors, which have been in use since 1905, can replace up to 30 laborers per machine Pacific American Fisheries cannery.

The machine in Figure 7 was initially called Iron Chink. The name itself reflected the widespread discrimination against Chinese workers at the time and was later officially renamed the Iron Butcher.

Chinese have not disappeared from the canneries with the dismissal of the contractor system; they have continued to appear in canneries ever since. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 did not forbid Chinese students from coming to the United States, and some of them came to Alaska and worked in canneries. Li, Gongpu was the most famous among them. In the summer of 1928, he worked at a cannery in southeastern Alaska. (11)

Li, Gongpu, a Cannery Worker

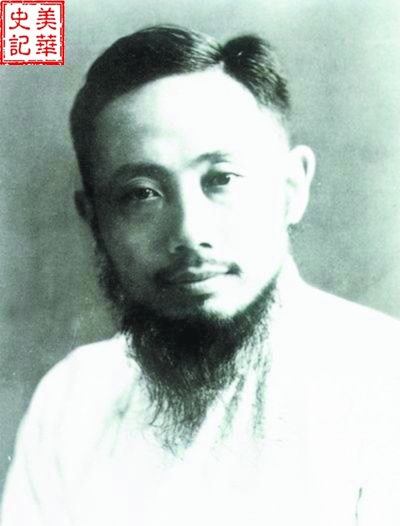

Li, Gongpu is a well-known Chinese political activist, educator, and one of the founders of the Chinese Democratic League. As a young man, he served in the National Revolutionary Army until mid-1927. At the end of the year, Reed College in Oregon (now was known as Reed University) came to China to recruit students. Applicants must be recommended by the Chinese Youth Association and serve as its staff after graduating from the college. Reed provided the scholarship for all accepted. Li, Gongpu passed the exam and was admitted to the Department of Political Science. His cannery worker experience occurred when he was an international student in Reed. He returned to Chine through Europe in the summer of 1930. During his time overseas, he frequently wrote newsletters and commentaries to introduce the Western democratic political systems to Chinese readers. May 1936, China was facing Japan’s aggressive invasion. China’s National Salvation Association was formed in Shanghai, and Li was elected as one of its Executive Members. On November 23, 1936, the Chinese government led by Chiang Kai-shek arrested seven leaders of the National Salvation Association, including Li, on charges of “endangering the Republic of China,” the event was known as the “Seven Gentleman Incident.” After the Second Sino-Japanese War outbreak in July 1937, all seven leaders were released.

Figure 8 李公朴

The Chinese Democratic League was founded after China’s victory of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1945, and Li was elected as an executive member of its Central Committee. He spoke out against the civil war and called for peace. On July 12, 1946, Li was assassinated.

Although many Chinese worked in canneries before 1928, they did not leave first-hand records; their lives and work were largely unknown. When Li and other international students came, the canneries were already filled by workers of all ethnicities. Li, Gongpu was a regular contributor to a Chinese language magazine in Shanghai, China, with good observation and communication skills. He wrote about his experiences in Alaska in a diary format. These diaries provided invaluable records, allowing us to see through his eyes the work and life of the cannery workers.

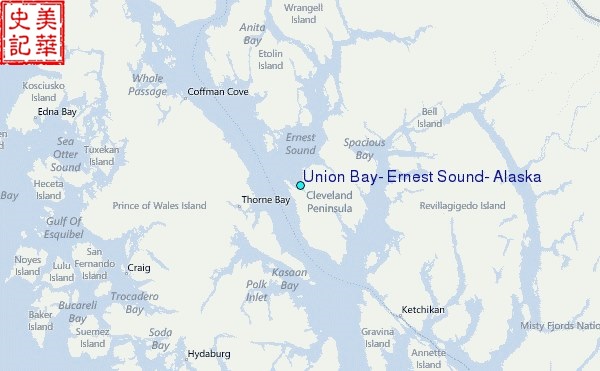

On June 23, 1928, Li started his work in Union Bay Cannery, 35 miles northwest of Ketchikan, Alaska.

Figure 9 Location of the Union Bay, Alaska.

Figure 10 Union Bay Cannery

Li, Gongpu described the environment and scenery of Union Bay in his diary:

“The factory is located onshore of Union Bay, where is not only plenty of fish but also splendid scenery. It faces the Pacific Ocean, and its back is a high mountain with a stream. A walkway next to the factory leads to the stream, and the cannery water comes from the stream. Pristine forests cover the mountains with old and big trees. We can sometimes see bears and deer, although bears are scarier. Even in summer, the snow on the top of the mountain makes us very cool.” He praised the “beautiful scenery here… Never tired of watching the sunset, walking, or fishing.” But “the factory is isolated from the outside world, except for a ferry delivering mails once every two or three weeks.”

He described the Union Bay Cannery and documented the procedures of salmon processing: “The cannery I am working in is the largest in the neighborhood, equipped with the state-of-the-art machinery. It can handle four to five thousand three-foot-long salmon, from cutting, cleaning, canning, cooking, labeling, and packing in a matter of hours.” The tasks in the factory “includes cutting fish, clearing fish, canning, making cans, and packaging. Many of the steps are done by machines.” On his duties and working hours: “My job is to operate the machines that make empty cans. The main thing is to put large pieces of tin into the first machine, which cut them into round pieces, and then another machine shapes them into empty cans. ” He “only stand in front of the machine and feed the piece of tin in. …… Compared with cleaning fish, this is an easy and clean job.”

He found the job was less stressful than he had previously thought: “It was easy the other days. But I’ve been doing eight or nine hours a day in the last two days. I thought I had to work ten hours a day, but it was actually only two or three weeks during the peak time with lots of fish coming. The other six or seven weeks, I only worked seven to eight hours per day.” “I had sour shoulders and knees in the first couple of days; now I’m doing fine even working nine hours a day.” He also thought about the factory owner, “This quiet day is good for the workers, but not good for the factory owner.”

After a while, Li was satisfied with his progress: “After a while here, I can say that my skills are as good as others: moving coal, carrying things, packing boxes, cutting woods, I can do all kinds of chores.” “I think I’m a lot more capable than I was at the beginning. I also enjoyed my leisure time reading. The other day, I caught two fish which were delicious.”

He had more time to observe those around him and write down his feelings. The first he noted the ethnic groups of workers, which he called the “Little United Nations”:

“Although the factory has only about a hundred workers, this place is like a small world, with people of all colors and nationalities. For example, Americans are white, Japanese and Chinese are yellow, Filipinos are brown, and Blacks originated from Africa. The workers are from China, Japan, the Philippines, Mexico, Italy, Switzerland, and other places. Most of the Chinese workers have been replaced by Filipinos. It’s hard to imagine such a small factory with people with so many different nationalities.”

He went further, noting the relationship between workers of all ethnicities: “From observing the contacts of these workers, I can feel the psychology of their different nationals. Whites came from more than thirty countries, about half of them with little education and only spoke simple English, but they felt like they were the most civilized people in the world. The Japanese are polite to Whites but arrogant to others. Filipinos are fond of showing off before the Reds and Blacks. And what about those Chinese? Although having the same color of skin like the Japanese, they are not treated the same as the Japanese. Such a situation may be because China has a rather low status in the world.”

Segregation among workers is widespread: “Workers of different races separated according to their races; they work, eat, and sleep in different places. Whites make themselves in one group, Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans are in another one, while Filipinos are in a separate group. Blacks and Indians eat and live together because they fish together too.”

He also wrote about the management and problems, noting in particular, the Asian and white workers were treated differently: “The labor-management in canneries used to go through a Chinese contractor, and he hired primarily Chinese. I heard that it was managed poorly. The accommodation was dirty, and the work was not done well. So this year, the owners had switched to Japanese contractors. Eighty percent of the workers are Chinese, Japanese, or Filipinos because they can sleep on hardwood beds, eat mainly white rice, and accept low wages. One time I went to the canteen for Whites, it was much better and cleaner than ours. That is because they are better paid and more used to cleaning.

In addition, Li noted that cultural and leisure activities vary from ethnic group to ethnic group: “Workers have different leisure activities. Whites like to play chess and cards, go fishing, chat, and sleep. The Japanese like to gamble and sometimes lose all their money. Filipinos love music, often dancing with red women by the river, and sometimes whites join the dancing. Once a while, the Indian women sang; the songs were beautiful, although I didn’t understand the words. Indians spend a lot of time on their boats, and I’ve heard that they sleep a lot when they’re not working.” (12)

Li’s after-work survey also revealed his concerns for the country and the people. He wrote that how the status of a state and the strength of a country affect a person is particularly visible at a place like here. It is particularly true for Chinese abroad and the residents in coastal cities such as Shanghai. “After the recent failures in domestic conflicts, warlords often go abroad, and we should hope that they would at least understand through their examines that the main reason for China’s low international status is due to the internal disputes and the political derailing.” “If they can repent, the rise of China’s international status will be in the near future.” (13)

The Union Eras

The Great Recession of the 1930s made jobs unstable. Filipino workers at canneries began to unite together to defend their rights. In June 1933, the Cannery Workers and Labor Farmer Union was founded in Seattle, and soon after, it became a member of a national union. (14) In 1938, the old labor contracting system was abolished entirely, and the channels to hire a large number of Chinese workers disappeared. Canneries had to hire workers through labor unions. As a result, wages significantly increased, and the working conditions were determined by negotiation between the labor unions and the cannery federation. The International Longshoremen and Dockers Union in Seattle is responsible for sending workers to eleven canneries in Alaska. Workers must join the Union, and each of the canneries must provide the Union with the amount workers it would need and their starting date before the fishing season began. The Union would assign its members based on their seniority and other undisclosed criteria.

Figure 11 Old Cannery Building, 213 S. Main St. in the Pioneer Square neighborhood, Seattle Washington Photo by Joe Mabel

Figure 12 Workers in a Ketchikan Cannery, 1940. University Washington Library Collection.

Fred Wong was born in Chinatown in Portland, Oregon. His father was a clerk at a cannery under the contract system. Fred graduated from high school in 1953 and began to work seasonally in the cannery. He worked in the cannery every summer during college, took tasks in every step of the fish processing, and made enough money to finish college independently. He joined the army in 1958 and returned to his cannery job two years later. In 1969 he was promoted as a foreman. The Union in the cannery was powerful and influential, with members overwhelmingly from the Philippines. One must get the endorsement by the Union to climb up to management positions. He obtained the Union’s support and became the only Chinese among the foremen. Although he became a salaried employee, he retained his union membership. Fred worked in the industry until his retirement in 2008. Not only himself, but he also introduced his daughters to work in canneries in Alaska. His extensive experiences made him an expert in the canning industry. He gave a detailed account of every process in a cannery in his memoirs. The stories of their three generations reflected the changing times of the industry. (15)

The peak canning season is during the summer break for college students. The income from summer can often support students’ expenses throughout the school year. Many high school and college students often take summer jobs in canneries. From 1970 to 1972, James and Philip Chiao, twin brothers from Taiwan, worked at three canneries in different parts of Alaska. Their memoirs provide us with a rich and informative record of student workers. (16) One of my colleagues spent several summers in canneries in the Aleutian Islands, often talking about stories in these remote and desolate coasts and short but busy summers.

Today, the National Park Service preserved some old canneries and village sites. San Francisco Maritime National Park has done detailed case studies of Diamond NN Cannery and documented the history of Chinese workers traveling north by boat. Glacier Bay National Park Reserve includes the Bartlett Cove Cannery Cove site. The Kake Cannery on Kupteanof Island in the southeast has become a national historic landmark. (17)

The Chinese workers had made significant contributions to the cannery industry in Alaska and the Northwest. Their history is Alaska’s history; their stories are a part of the national memories of the U.S. Such history and memories cannot be ignored and forgotten; they must be documented and passed on.

References

- Tara Neilson: Li Gongpu: Undercover cannery worker in 1928, Juneau Empire October 26, 2017. https://www.juneauempire.com/life/li-gongpu-undercover-cannery-worker-in-1928/

- 李公朴 – 维基百科,自由的百科全书 (wikipedia.org)

- Canneries of Alaska (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

- Anjuli Grantham: Chinese Labor Contractors and the Early Salmon Canning Industry http://www.anjuligrantham.com/ May 2018

- 水文:天涯筑路人的足迹 https://usdandelion.com/archives/2362

- Alaska Humanity Forum History and Cultures http://www.akhistorycourse.org/southeast-alaska/1873-1900-developing-southeast-alaska/

- Asians In the Salmon Canning Industry,mar-apr-may-2009.pdf (npshistory.com)

- Margaret Riddle: One hundred and fifty Chinese workers bound for salmon canneries at Blaine leave Seattle on April 2, 1900. https://www.historylink.org/File/10919

- Emergency Quota Act https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_Quota_Act

- Department of State, Office of Historian https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act

- Chinese Workers in Salmon Canneries https://chinesecannerylaborers.home.blog/

- Li Gong Bu in Alaska https://sway.office.com/ykT9pEDTXCUbVQDm?ref=Link

- Li Gong Bu《工余见闻与感想》,《李公朴文集》P47贵州人民出版社1987年

- Crystal Fresco: Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union 1933-39

- Fred Wong in Ketchikan & Alitak, 1953-2008

- James Chiao and Philips Chiao: 喬家兄弟 Chiao Brothers in Alaska 1970-1972

- National Park Service: Canneries of Alaska https://www.nps.gov/articles/series.htm?id=D1DEE2CB-E9DC-F99A-A14FE13BC466AB90

Li Gongpu and Chinese Cannery Workers in Alaska

Abstract

For several decades following 1870, Alaska salmon-canning industry has depended heavily on the labor of Chinese immigrants. They cleaned and packed salmon in many canneries along the Alaska coast, from the Southeast, Kodiak Island to the Aleutian Islands.

Chinese cannery men worked under labor contractors who played the bridge between the Chinese crews and the cannery owners. After 1885, canneries faced worker shortages due to the impacts of the Chinese Exclusion Act. A wave of Japanese workers arrived to fill the void partially. The contract-labor system began to come apart in the first half of the 1930s; cannery workers established their Unions. Although no longer the dominant workforce then, Chinese Americans have always contributed to the fish-canning industry.

In 1927, a well-known Chinese social educator, Li Gongpu, came to the U.S. to attend Reed College in Portland. He worked at the Union Bay Cannery in southern Alaska during the summer of 1928. Requested by an editor of a Shanghai-based Chinese-language magazine, Li contributed several articles about his life and working experiences in Alaska. He may have been the only one among the tens of thousands of Chinese laborers before WWII who had left us with the invaluable written record of Alaska cannery life.