Author: Xin Su

Editor: Qiang Fang

Translator: Joyce Zhao

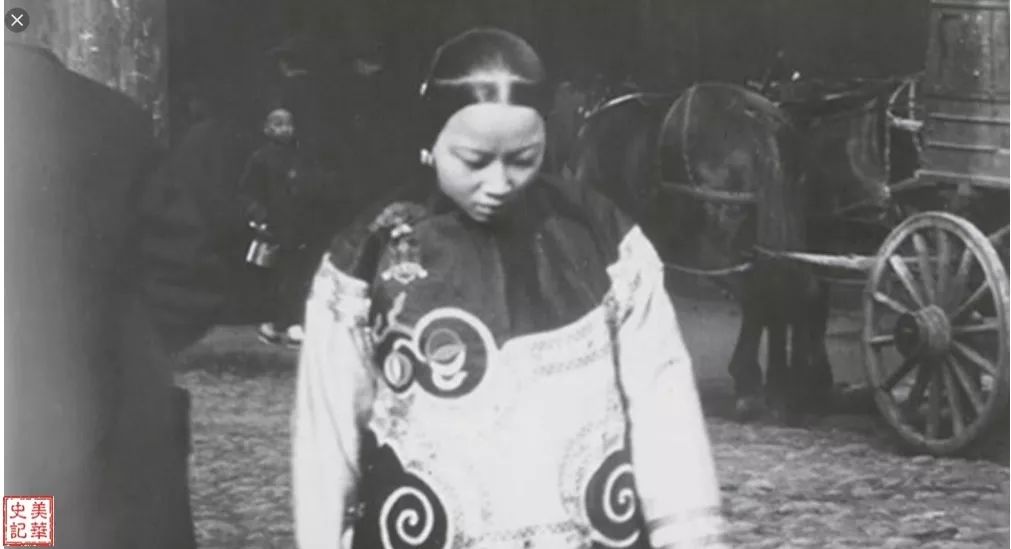

Chinese women in the 19th century were a special group in American Chinese communities. Some of them were babysitters, laundry workers, or gold diggers. This group of people formed the first batch of families in the Chinese community and raised Children, so their families grew generation after generation. Prostitution was quite common among many ethnic groups in the western United States, and many Chinese women were also prostitutes. The U.S. legislative system passed the Page Act, prohibiting so-called cheap labor and immoral Asian women from entering the United States. Their excuse for discriminating against Chinese women was their image of prostitution, spreading sexually transmitted diseases, and subverting American marriage ethics. With restrictions on female immigration, the federal government successfully prevented the growth of the Chinese population.

Chinese Women, an indecent class

During the gold rush, there was an extreme shortage of women in the western United States, and prostitution was quite common among many ethnic groups in the western United States. The earliest prostitutes came from France and other European countries. Some also came from New York, New Orleans and other cities in the United States. Then, there were women from Mexico, Peru and Chile. Prostitution in the Chinese immigrant community was a serious problem in San Francisco. In 1860s San Francisco, more than 90% of Chinese women worked in brothels. In 1870, this proportion dropped to just over 60%. These girls were turned into prostitutes through either sale or deceit. Some Chinese in San Francisco arranged the transportation and sale of prostitutes in the city [1].

So what kind of people were these despised women?

Most of the women in the dust were young, and some were even sold off as infants. As the family name is not passed down by the girls, Chinese traditional culture favors boys over girls, and it was not uncommon to abandon female infants. Newborn girls could be abandoned in a basket, and some little girls were tied to the head of Chaozhou city, where anyone who wanted a baby girl could take it away. The middleman transported little girls to the United States for sale through acquisition or deception. When entering customs, the middleman bribed the immigration officials of San Francisco Customs. There were also girls who were transported by ship captains to hand over or sell to contractors. Some girls entered rural towns by train or carriage by themselves, and some entered the country from Canada or the coastal bays of the Pacific Ocean [2].

After 1860, the profitable trade in girls in San Francisco was controlled by criminal gangs. The criminal gangs put the girls in baskets and imported them into San Francisco in bulk as goods. Some companies often had as many as 800 girls, ranging in age from two to 16 years old [2].

The sale was clearly marked. If women were sent into mining areas and carpentry towns to sell to workers, then the middleman would have to hire bodyguards to escort them. Each woman ranged from $200 to $500 per head [2].

The girls were called “Mui Tsais” and served as maids to wealthy people. After 18 years of age, they could marry and redeem themselves. They could not leave their employers freely, and they were often physically abused or reduced to a tool for their masters’ desires. Wealthy Chinese men and women could pay $80 to buy a girl shipped from China. The price in the San Francisco slave trade market or underground basement was expensive — between $400 and $2,000. After the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the price for a one year old girl was $100, and the price for a 14 year old girl was $1,200 [2]. Chinese prostitutes often had contracted syphilis. Carrying sexually transmitted diseases was a sin. Their ending was tragic. When they fell ill, they were often thrown onto the streets or locked into a small room, left completely alone until they passed away.The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery and forced labor, and it contained regulations prohibiting indentured slavery [3]. In order to evade legal punishment, trading transactions had to be conducted in secret. The girl had to sign an agreement by herself, agreeing to sell herself as a prostitute for several years. If she fell sick for one day, the contract was extended by two weeks. If she fell sick for more than one day, it was extended by one month. If she escaped from the master’s house, she was detained as a slave for life. The sick period included the menstrual period, so the contract was actually just indefinite [2].

In the lively San Francisco, there was a kind of “pigeon cage” on the side of the street. A deceived girl was locked in a cage to attract passerbys. When a white person or client arrived, the madam or the owner opened the door and closed the curtain to provide a private space for the girl to entertain the client. The highest fee was 25 cents, and some spent 10 cents to “peek” [2].

From 1854 to 1865, the San Francisco police used forceful methods to deal with the “pigeon cage” prostitutes, driving them from the downtown area to the back streets and alleys. In 1865, the police stepped up their efforts to drive Chinese women out of San Francisco [2].

Many Chinese prostitutes suffered cruel torment. In 1860, a coroner reported that a young Chinese prostitute died in an inexplicable manner and was buried hurriedly in a Chinese cemetery. When she was excavated for an autopsy, the coroner found that her neck was broken and her whole body was bruised [2].

A few girls opened up a way to survive under the pressure.

The Cantonese woman Ah Toy (1828-1928) was a legendary Chinese woman. During the California Gold Rush in 1849, Ah Toy set out with her husband from Hong Kong to San Francisco. That year, she was only 20 years old with bound feet, a tall figure, and a pair of smiling eyes, full of charm. On the way to the United States, her husband unfortunately passed away. So Ah Toy became the captain’s mistress, and the captain splurged a lot of gold on her. When Ah Toy arrived in San Francisco, she already had a small amount of money [1].

At that time, the ratio of males to females in California was 92 to 8, and the arrival of any woman would cause a sensation [4]. Because Ah Toy was so stunning, many men were more than willing to spend money to take a closer look at her (lookee). She charged one ounce of gold every time she was seen (16 dollars, which is equivalent to the current 560 dollars [5]).

Ah Toy was also enthusiastic about public affairs. When California became the 31st state in the United States in 1850, Ah Toy called on the local Chinese to celebrate this historical moment together. Before 1851, there were only 7 Chinese women in the city of San Francisco. Soon, Ah Toy became the highest-paid and most famous prostitute in San Francisco. It is said she was also the first Chinese prostitute in San Francisco[1,5].

Ah Toy spoke English, had strong opinions, and was very intelligent. She often protected her profits from the exploitations of the Chinatown government by appealing to the San Francisco court. According to a report [6], Ah Toy went to court because some clients had used brass shavings as gold when they paid. At that time, she had an elegant hair bun wrapped on her head and thin, black eyebrows. Wearing an apricot satin waistcoat and willow green pants, her small feet were wrapped with colorful shoes. Her dazzling brilliance reminded people that clients may not just be after her looks [6].

At that time, not only men who opened brothels in Chinatown, but also women did. A year or two later, Ah Toy became a madam herself and owned several prostitutes. She was a successful businesswoman, and she later opened a chain of brothels, inviting young girls from China. Some girls even started working for her at the age of eleven. The Chinatown government constantly tried to control Ah Toy and her business. In 1854, local legislation stipulated that the Chinese could not testify in court, and Ah Toy lost her legal protection against bullying and oppression. In the same year, the anti-prostitution law against the Chinese was promulgated. Ah Toy was also arrested several times for having a “dirty room”, while her white colleagues were exempt from prosecution [4]. John Clarke, a lover of Ah Toy, who served as a prostitution investigator in Chinatown, helped Ah Toy a lot. In 1857, Ah Toy sold the property and withdrew from the prostitution industry in San Francisco [1].

Ah Toy went back to China later, but in 1868 she returned to California again. After she got married, she raised her family by selling clams in Alviso in South Bay [6], and she lived a peaceful and comfortable life [1]. As spring passed and autumn came, the flowers bloomed and withered, Ah Toy slowly faded out of people’s sight until she died in 1928 at the age of one hundred years and three months [1].

Suey Hin was a slave girl and asloowned 50 prostitutes of various ages. Suey Hin was originally from Shandong. When she was five years old, she was sold by her father for a piece of gold. When she was 12 years old, she was resold to San Francisco for three handfuls of gold. She had been a prostitute for ten years before she met a poor laundry man who loved her. The laundryman saved up 3,000 U.S. dollars to redeem her from the kiln, get married and start a family. Happiness lasted only three years, and the poor laundry worker fell ill and died. Suey Hin lost all support and had nothing but herself. Thus, she restarted her old business and went to China to buy the first batch of eight girls. Claiming that they were her own children, she brought them into the United States [1].

What happened in the meantime is unknown, but she later tried her best to help the girls. In 1898, she sent a girl kidnapped by her back to China and at the same time, rescued seven others through the help of the church, promising to find a Christian husband for them [1].

If girls were sold to a good family, the situation would be completely different.

Quan Laan Fan was a “Mui Tsai” who came to the United States in the 1880s. Because a litter of pigs died when she was seven, her family owed debt. Left with no other choice, her parents sold her to a San Franciscan Hakka as a maid. She came to the United States with the family and lived a comfortable life. The master opened a vegetable shop, and the mistress stayed home. Fan was responsible for bringing food to the mistress from the vegetable shop every day. In addition, she was able to rely on rolling cigarettes to earn some money for her family in China. At the flowering age of eighteen or nineteen years old, she married, opened a flower shop with her husband in Belmonte, and then returned to San Francisco to work as a telephone operator in Chinatown. She had eight children, and she led a happy life [1].

Page Act in the Name of Morality

On February 18, 1875, California Republican Congressman Horace F. Page submitted a draft of an immigration law that restricted “undesirable” groups of people, including cheap Chinese laborers (“coolies”), immoral Chinese women, and domestic criminals [7]. Anyone who tried to bring such people from China, Japan, or other Asian countries to the United States was punished with a fine of $2,000 and a maximum sentence of one year in prison.

This proposal passed through vote in the House of Representatives on February 22, 1875. On the same day it passed through the Senate on March 3, 1875, it was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant (Sect. 141, 18 Stat. 477, 3 March 1875 [8]). In his seventh annual address to the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, the President reiterated the United States’ concerns about the immigration of women from the Far East.

The “Page Act” did not effectively reduce “coolie” laborers and criminals in its implementation, but it was more specifically aimed at Asian women, especially Chinese female immigrants. They were viewed as criminals who engaged in prostitution once they came to the United States. The American consul in Hong Kong, David H. Bailey, implemented a measure from 1875 to 1877 — that women must submit immigration and personal ethics declarations before immigrating to the United States. The statement was then taken to the hospital for careful examination and reported on the personality of each woman. Chinese women had to be questioned many times at the consulate, on the ship, and at customs. The question was directed at her female role and her relationship with her father and husband. Officials judged women’s sexual prospects based on the answers. Some officials tried to distinguish between prostitutes and real wives by examining the physical clues of Chinese women, including leggings, behavior, and their walk. However, it was practically impossible to distinguish between wives and prostitutes. From 1875 to 1882, at least a hundred, and possibly hundreds of women, were sent back to China. The whole process was defined by a larger and clearer assumption: Chinese women were as dishonest as Chinese men [9].

The chase and expulsion of Chinese women

In order to protect themselves and escape the fate of being enslaved, many Chinese prostitutes fought against the odds and fled alone. They took great risks and fled from one community to another. Behind them was a group of people in hot pursuit. The pursuer could’ve been the owner or the so-called “husband.” If the prostitutes fled to the police station, the police could detain them and then send them back to their “husbands” or masters for rewards. In 1877, San Francisco’s Chinatown hired special security guards with a fixed salary to arrest fugitive prostitutes and squeeze rewards out of madams and owners [2].

Prostitution yielded huge profits. Some Chinese communities had ways to “protect” their own prostitutes. The struggle around prostitution had split Chinatown in jealousy. In December 1872, in order to compete for a woman, Xinmei, the Chinese men even shot and wounded each other. In January 1873, two groups of men went to court, arguing nonstop. The long trial made it difficult to tell the true from the false. Such stories became the perpetual gossip in newspapers [2].

In addition to being chased by Chinese men, Chinese prostitutes also faced the animosity of white people.

On April 30, 1876, riots broke out in the small town of Antioch, 40 miles northeast of San Francisco. More than 40 white men and women, in groups of five, rushed to Chinatown. They pounded on the door of the brothel, warning the women to leave before 3’Oclock in the afternoon, save for the Chinese men. There was a reason for the incident. It turned out that seven noble and high-ranking white sons contracted syphilis after fraternizing in the brothel. The root of evil could only be traced back to prostitutes[2].

The general public believed that 90% of Chinese prostitutes in San Francisco carried STDs. When 10-12 year old boys went to brothels seeking prostitution, the blame was pinned on Chinese prostitutes. Dr. Hugh Toland of the San Francisco Department of Health claimed that a particularly severe case of syphilis that infected a five-year-old white boy stemmed from a Chinese prostitute. This testimony occupied the national newspapers for a long time — how appalling[2]!

Speaking of the small town of Antioch, many Chinese women came to this riverside town as sex slaves who fled San Francisco, but they were actually very eager to stay. However, when they were ordered to evict their guests, the women hurriedly rolled up their clothes and bedding with turbans and shawls, stuffed them into baskets, and carried all their belongings on their shoulders while fleeing to the dock. Among the fleeing crowd were Chinese contractors, middlemen, and prostitute owners. They hurriedly boarded a fishing boat and went straight to Stockton [2].

The next afternoon, there were rumors that the Chinese women had returned. At 8’Oclock in the evening, Chinatown was set on roaring fire. The newly established fire brigade allowed the fire to spread and refused to organize and put out the fire. The residents of Antioch watched the excitement. In the end, Chinatown was burnt down to only two houses. On the morning of the third day, the two remaining houses were also destroyed. The remaining Chinese each bought a 25-cent ferry ticket and fled to San Francisco by ship [2].

The local newspaper cheered: this disgraceful class has disappeared from Antioch[2]!

Woman flowers swaying in the nineteenth century

The Presbyterian Mission House rescued many “Mui Tsais”. With their help, many Chinese girls met their own Prince Charmings. As if in a fairy tale, they lived happily ever after.Mary Tape (1857-1934) was one of those.

In 1868, she immigrated to the United States alone as a minor. Fortunately, she was helped by thePresbyterian Mission House in San Francisco where she learned English, and became an amateur photographer and artist. In 1875, she married Joseph Tape (1852-1935), who was born in China and a businessman and interpreter for the Chinese Consulate. After marriage, they had four children[1].

When Mamie Tape, their 8-year-old daughter born in San Francisco, applied for admission in 1884, public schools refused to accept Chinese children. The Tapes rose up in resistance and sued the San Francisco Board of Education (Tape v. Hurley). The Tape couple believed that the school board’s decision violated California law that states: “every school, unless otherwise provided by law, must be open for the admission of all children between six and twenty-one years of age residing in the district … Trustees shall have the power to exclude children of filthy or vicious habits, or children suffering from contagious or infectious diseases.”. Mary Tape bravely wrote to the San Francisco School Board to express her indignation. She was confident and full of fearless courage. On January 9, 1885, Superior Court Justice McGuire declared that the Tapes won.

In the late 19th century, many Chinese women married laborers who had settled in the United States. Some of these women used to be prostitutes, and some were born and raised in the United States. They were not as laid back as business men’s wives and needed to work to support their families. These people worked in various occupations to support their families, such as laundry workers, gold panners, kitchen assistants, seamstresses, babysitters, farmers, or shop assistants. In a typical Chinatown family, the husband was nine years older than the wife, forming a family of three or four with one or two children [1].

It was this group of great Chinese women who built the first batch of families in the Chinese community and nurtured children, so their families grew generation after generation.

Restrictions on Female Immigrants to Prevent the growth of the Chinese population

The family is a basic form of society established to satisfy the daily lives of human beings: the fire companion, the natural needs of physiology. The serious imbalance in the ratio of men and women exacerbated the problem of life without a family in Chinatown in the United States. The wealthy were able to pay immigration fees and bribe American consulates to import prostitutes into the United States. Some Chinese women were forced into prostitution to repay the travel expenses of moving to the United States, and the wives of some Chinese workers were kidnapped and sold to brothels [10]. The Page Act encouraged the crime it claimed to fight: prostitution.

In the United States, slavery and involuntary servitude were abolished in 1865. Many Americans believed that both male Chinese “coolie” laborers and female Chinese prostitutes were related to slavery [12]. A slave refers to a person who does not belong to his own person, but belongs to others — becomes the property of others — where the owner has the freedom to transfer or sell ownership. The Chinese obviously had personal freedom, and they were not other people’s property (goods). Although some Chinese workers or “Mui Tsais” had signed contracts, this did not automatically make them slaves. It is true that the native culture of the Chinese is absolute obedience to the emperor and master. The continuation of this concept makes the soul lack confident logical reasoning and more likely to be enslaved. This behavior has undoubtedly increased the hostility of American society towards the Chinese.

The Page Act’s regulation of immigrants around sexual activity gradually expanded to every immigrant entering the United States. The creation of the Page Act was based on concern for the fate of white people and their families:

- Chinese women caused disease transmission to white men, impacting the physical health of white men [8]. It is worth mentioning that the anger of the people was because the victims suffering from syphilis were white men, not white women or Chinese men. And syphilis seemed to spread only one way, from Chinese women to white men. No one cared about the status of Chinese sex slaves, and no one investigated whether female slave smuggling was ethical.

- Chinese prostitutes posed a threat to the ideal American family. Americans value protecting the social ideals and morals of marriage, which includes protecting the monogamous marriage system. Some Chinese men had wives and concubines, and they could legally buy women to become lower-level members of the family. If this cultural custom became a part of American democracy, it would seriously threaten public ethics and their values [12].

Emphasizing morality and keeping an eye on prostitution was only a strategy. The real motivation of the Page Act was to protect the competitiveness of white Americans in the labor market. The bill was used by legislators to restrict the entry of Chinese women in the name of morality, forcing Chinese men to return to China. It ensured that the western United States would not reside a long-term Chinese ethnic group [9, 12]. When stealing in the name of morality for political gain, its influence and danger cannot be ignored.

Not all women who immigrated to the United States in the 1860s and 1870s were prostitutes. The implementation of the Page Act not only led to the reduction of prostitutes, but it also wiped out the Chinese women population in the United States. In 1855, women accounted for only 2% of Chinese Americans, and in 1875, this proportion was about 4% [2]. In the months before the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and when enforcement began, 39,579 Chinese entered the United States, of which only 136 were women[11].

The consequence of the Page Act was to cause a serious imbalance in the ratio of men to women in Chinese Americans. It successfully prevented female Chinese from immigrating and aggravated the imbalance between men and women, making it difficult for Chinese men to establish a family in the United States. Relying on restrictions on female immigrants, the federal government succeeded in preventing the growth of the Chinese population.

References:

1. Judy Yung. Unbound feet: A social history of Chinese women in San Francisco. (University of California Press, 1995): p25-51.

2. Jean Pfaelzer. Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans. (University of California Press, 2008): p89-120.

3. “13th Amendment”. Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. November 20, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

4. Iris Chang. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. (Penguin, 2003): p35.

5. Anjana Venugopal, “Badass Ladies Of Chinese History: Ah Toy Most definitely not an Asian doll, this Chinese femme-fatale took the Wild West head-on” January 27, 2016. http://www.theworldofchinese.com/2016/01/badass-ladies-of-china-ah-toy/

6.“Wild West Women: Ah Toy – A China Blossom in Old San Francisco.” May 21, 2017. https://worldhistory.us/american-history/this-wild-wild-west/wild-west-women-ah-toy-a-china-blossom-in-old-san-francisco.php

7. George Anthony Peffer, “Forbidden Families: Emigration Experiences of Chinese Women Under the Page Law, 1875-1882,” Journal of American Ethnic History 6.1 (Fall 1986): p28-46. p28.

8. “An Act Supplementary to the Acts in Relation to Immigration (Page Law)” sect. 141, 18 Stat. 477 (1873-March 1875).

9. Eithne Luibheid. Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border. (University of Minnesota Press, 2002): p34-53.

10. George Anthony Peffer, “Forbidden Families: Emigration Experiences of Chinese Women Under the Page Law, 1875-1882,” in Journal of American Ethnic History 6.1, Fall 1986, p34-43.

11. Kerry Abrams. “Polygamy, Prostitution, and the Federalization of Immigration Law,” in Columbia Law Review 105.3, Apr. 2005, p641-716.

12. Ming M. Zhu, “The Page Act of 1875: In the Name of Morality”, March 23, 2010, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1577213