Author: Zhida Song-James

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

Although they lost the lawsuit at the US Supreme Court, the case, Lum v. Rice, laid the foundation for the Brown v. Board of Education decision (1954) which finally ended school segregation. This story demonstrates the great contributions made by Chinese-Americans in defending the US constitution, and though the impact of their actions were not readily recognized, they are significant and everlasting.

~~~~

Some have said that the Chinese are only passersby–that they come here to make money and get rich and go home. This story that took place in the 1920s Mississippi Delta tells us the truth: not only are they not passers-by, but the Chinese have made unique contributions and sacrifices in defending the Constitution’s values of equality.

In October of 1927, the Supreme Court received a case from the southern state of Mississippi. The case was labeled Gong Lum, et al v. Rice et.al (275 US 78) [1]. This grand and noble building held supreme authority on the land of the United States of America. Here, the highest adjudicators of American law have made many final decisions on appeals from across the country in accordance with the U.S. Constitution. Their final judgment determines the fate of each person involved in the case. Not only that, but in the United States, the Supreme Court upholds the concept of precedent: the verdict of each case can be cited in subsequent cases and become the basis for judgment. Therefore, the Supreme Court’s decision in each case has an extremely broad and far-reaching impact on future generations. At the time, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was William H. Taft, who had also served as President of the United States from 1909 to 1913. The other eight judges were Oliver W. Holmes (Massachusetts), Willis Van Devanter (Wyoming), James C. McReynolds (Tennessee), Louis Brandeis (Massachusetts), George Sutherland (Utah), Pierce Butler (Minnesota), Edward T. Sanford (Tennessee), and Harlan F. Stone (New York) [2].

Picture 1: Supreme Court Justices of the United States of America in 1927, source: wjbc.com

In this case, the plaintiff was a Chinese family headed by Gong Lum, represented by lawyers James N. Flowers, Earl Brewer, and Edward C. Brewer. The defendant was the Bolivar County board of directors of the Rosedale Consolidated School District, headed by Rice. Also on their side was the Mississippi Supreme Court, represented by Mississippi State Attorney General Rush H. Knox and his assistants. Obviously, this was a fight with great disparity in strength. Chinese mother Katherine Lum and her family anxiously awaited the Supreme Court’s decision.

Picture 2: Interior view of the Supreme Court in 1927, source: https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/photos.aspx

Chasing a dream

Katherine Lum, or Katie as she was referred to by her friends, was orphaned at a very young age. She was adopted by a wealthy merchant family surnamed Huang. She grew up in Gunnison, north of Rosedale. Her foster parents treated her very well. According to custom, she lived in her foster parents’ house until she was eighteen years old, and then she was free to marry. In 1912, she met Jue Gong Lum shortly after she turned eighteen. His English name was Gong Lum, as documented on the plaintiff’s side of the case.

On a cold winter night in 1904, Gong Lum crossed a frozen river and entered the United States from Canada undocumented. Relatives in Detroit helped him take the train from Chicago to the Mississippi Delta. The climate there was warm, the land was flat and fertile, and the water was abundant, making it very suitable for growing cotton. Before the Civil War, large plantations spread over the area. A small number of white manor owners dominated the economic lifeline of the South by enslaving Black laborers, and slaves paid high prices to the manor owners to gain personal necessities. After the Civil War, two completely isolated societies, white and black, formed in the South. This state of isolation, however, allowed the Chinese uncommon business opportunities and a chance at survival. After the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, Chinese people in the United States could not own land or houses, so there was no way to survive except by doing business. Grocery stores owned by the Chinese began to appear on the fringe of black residential areas in the Delta. Black people welcomed these grocery stores, not only because the prices were reasonable, but also because buying things in these stores was a sign that they had freed themselves from the control of the plantation economy. Gong Lum found a job in such a Chinese-owned grocery store. His illegal immigration status kept him cautious. He kept his distance from white people. In June 1913, Katie and Gong Lum married, and they opened a small shop of their own in the small town of Benoit to start a new life.

Katie quickly adjusted to her new home. She grew up in the Delta and spoke fluent English, making it easy for her to get along with others in town. She cooked delicious southern dishes, entertained guests with sweet iced tea, and like most southern women, she sported a cigarette between her delicate fingers. Katie grew up in a Christian family. Every Sunday she closed the shop, and with a parasol in hand, walked to church along the streets lined with magnolia trees. Usually, the couple was busy from morning to night running the small shop, in hopes of living a prosperous life like Katie’s adoptive parents. They named their first child Berta, which was similar to the name of the daughter of the town’s mansion owner. Their second daughter, born in 1915, was named Martha, after a kind-hearted school teacher that they knew. When their son was born a few years later, they named him Biscoe, after the mayor of Benoit at the time[3]. Katie insisted on taking her children to church, wholeheartedly hoping that her children would prosper in this new land.

After their two daughters were born, their house behind the shop became too cramped for the family of four. In 1919, Gong Lum got a loan to buy a quarter acre of land in the east end of Rosedale Town. After four years of hard work, the Lin family built the house of their dreams. Downstairs was the store, which Gong Lum carefully divided into several parts according to the types of goods; behind the store was the vegetable garden, which grew a variety of long beans, eggplants, and squashes. Upstairs was Katie’s world, with a total of eight rooms. She wanted a spacious place in order to accommodate her adoptive parents and Gong Lum’s brothers and relatives in the house. Moreover, the two-classroom school in Benoit was too cramped, and Katie wanted her children to receive the best education. Moved to Rosedale and opened a new store. Katherine Lum believed that her dream was being fulfilled step by step.

Shattered Dreams

The older sister Berta was a bit rebellious, while her younger sister Martha had always been a good student. In 1924, the two little girls were studying in the third and fourth grades. September 15 was the first day of school. Katie combed her daughters’ hair, put them in skirts that she made herself, and watched them as they walked to their new school in Rosedale. It was a new school that had only been built in recent years. It had large school buildings, snow-white walls, meticulously crafted doors and windows, and sufficient teachers. What residents were most proud of was that the school passed the strict review of the State Board of Education, and high school graduates could directly enter the State University. It was undoubtedly first-rate in the Delta. However, Katie was very unsettled at that moment. In recent months, she had heard rumors that the school would enroll more white children and that Chinese children would not be able to attend in order to make room for them. She knew that there had been violent threats against Black people nearby, and she also knew that people in the church participated in KKK activities. But if she bowed her head and retreated because of this, giving up on sending her daughters to school, it wouldn’t be our Katie. She told her daughters that no matter what happened at school, don’t be afraid! At noon, their daughters returned. The newly appointed principal, Nat, told them that the Mississippi State Attorney General determined that under the policy of segregation, whites only meant that only “Caucasians” could attend. Based on this, the Rosedale Consolidated School Board decided that Chinese children would no longer be allowed to attend the school. The principal said there was nothing he could do.

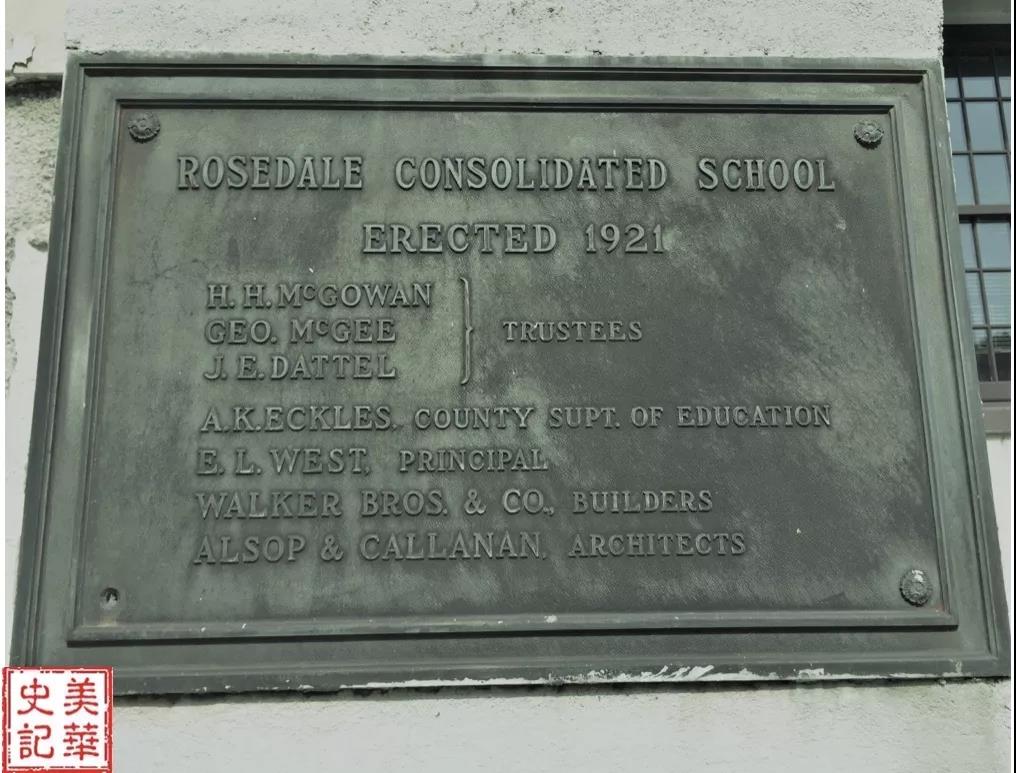

Picture 3. The Rosedale Consolidated School, taken by the author in 2018.

Picture 4: The nameplate of the Rosedale Consolidated school, including the name of the school manager when the school was founded in 1921. In 1924, McGowen remained on the board of trustees. Taken by the author in 2018.

This was a harsh blow to Katie. Growing up in the segregated Delta, she knew exactly what it meant that her children were classified as “colored.” A fierce sense of motherhood possessed her. The strength and courage that built up from this seemingly weak southern beauty burst out overnight: no matter how powerful the force she was facing, she would do her best to fight for the education of her daughters. She heard that a lawyer had helped out another Chinese-American, so the couple decided to go to him and go to law. This lawyer was former Governor Earl Brewer.

Picture 5: Earl Brewer on the river bank Source: http://eetheridge.posthaven.com/earl-brewer-mississippi-governor-1912-16-and

The Fourteenth Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed on July 9, 1868. It is one of the three reconstruction amendments passed after the Civil War. This amendment involves civil rights and equal legal protection.

The Fourteenth Amendment had an enormous impact in American history, and a large number of judicial cases have since been based on it. In particular, the first paragraph, also known as the Equal Protection Clause, requires states to provide equal legal protection to anyone within their jurisdiction. Many lawsuits have been brought forth using this Amendment. Famous Chinese-related cases such as the United States v. Gold (169 U.S. 649 (1898)) and Yihe v. Hopkins (118 U.S. 356 (1886)) are based on its legal premise. The first section goes as follows:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Attorney Brewer shrewdly realized that Katie handed him a case that violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The original intent of the equal protection clause was to protect the civil rights of Black citizens, but he believed that the same applied to protecting all citizens. In the complaint he wrote, “Martha is a nine-year-old girl born in Mississippi, an excellent elementary school student. She was expelled from a ‘white’ school just because of her race and because she is a descendant of Chinese, which violates the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution that states ‘no one shall be denied equal legal protection.’” He also said that according to Mississippi law, anyone between the ages of 5 and 18 could not be prohibited from going to school. This meant that Martha’s right to go to school was also protected by Mississippi state law. Nonetheless, all the school directors–L. C. Brown, Greek. P. Rice and Henry McGowen–were listed as defendants [4].

News of this incident soon spread far and wide across the towns of the Delta. Brewer’s political opponents attacked him for representing the Chinese, believing that he was forcing whites out to send Chinese children to their schools. But the defendant Greek. P. Rice’s son, Greek Rice. Jr. who was studying law, and his classmate IJ Brocato, stood on Brewer’s side and wrote an article accusing the attackers: whether they were Chinese or any other race, they had the right to education. He sharply said, “Get a fair and capable lawyer in court. Those of you trying to deprive and veto their natural rights are violating the Constitution that you once vowed to be loyal to.” [5]

Unsurprisingly, the school board argued that Martha was not allowed to attend the school on the basis of Article 207 of the Mississippi Constitution: The school implemented a white and black segregation system. Because Masha was of “yellow race”, she could only go to a school for “colored races.” On November 5, 1924, the Judge of the Circuit Court, William Alcorn, dismissed the defendant’s plea and ordered the Rosedale Consolidated School to accept Martha back to school.

Did they win?

The school board and its beliefs of strong racial segregation did not stop there. They knew that the longer they dragged out the case, the worse the outcome would be for Martha’s family. On December 15, the school board appealed to the state supreme court. In the appeal, the state attorney general became the lawyer for the school board. Faced with such a powerful force, the Lums’ still managed to stand strong. At that time, no other Chinese joined their ranks, and they decided to continue fighting alone.

The state Supreme Court fully understood the impact of this case and treated it with great importance. The Court classified the case into its highest priority category, which required all six judges to appear in court for hearing. One of the judges, George H. Ethridge, though he was a teacher, strongly supported the policy of segregation. In court, the state lawyer representing the school board said, “Mississippi’s policy has always been that white schools are reserved for Caucasians. The wish of the legislators in this state is to prohibit any other race from interacting with whites and white children. Martha and all other Chinese children should be classified with “Negros.”’ He emphasized that Mississippi implemented the segregation system to protect the interests of white people, and that there was no need to bring the rules of the Constitution into the case. Let us remember the name of this segregation defender: Elmer Clinton Sharp, Assistant Attorney General of Mississippi.

When it was Brewer’s turn, he pointed out that when the segregation system was established in 1890, there were only Black and white people in Mississippi. His weapon was still the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Martha was a child of the state of Mississippi, so regardless of her skin color, she had the privilege of receiving education in the state’s public schools. He asked the court not to regard her as a Chinese or “yellow” child, but as a state citizen with equal rights. He asked the state to do something that had never been done before: first treat this elementary school student as a citizen of this state, rather than an outsider just because of her race.

Such a request was made first in 1924 in the state of Mississippi, loud and clear. But by winter, their voices were still not strong enough. The state Supreme Court unanimously ruled that because Martha was not white, she was not permitted to enter the white school in Rosedale. The school board got the verdict they wanted. Brewer lost, the Lum family lost, and the racists temporarily won. What is more unreasonable is that their decision was based on another case, Moreau v. Grandich, in which the judges ruled that a child should be expelled from school just because of rumors that her grandmother was of African descent.

Vote with one’s feet

When this news reached Katie’s house in Rosedale Town, one can only imagine how brutally it affected them. Martha, who loved to study but had to do so at home for many months, was especially devastated. Katie knew that if she did not continue fighting for her children’s education rights, their family’s American dream would never come true. The determined woman decided that she must find a place for her child to go to school. Gong Lum had an older brother who ran a laundry shop in Jackson, Michigan. There were no segregated schools in Michigan. The couple decided to send their three children to attend schools there. In May 1925, 11-year-old Berta took 10-year-old Martha and her 6-year-old brother on a train to the far north, sitting in a carriage marked for the “colored.” There were many immigrants in Jackson, and there were several schools with descendants of immigrants from various countries such as Germany, Poland, Ireland, and Italy. All the children in the school were treated equally, which soothed the hearts of the young children.

From then until the 1930s, there was a great migration of southern Black folks to the northern states in the United States. Many Chinese families joined this mass migration. The segregation and discrimination was one of the main factors behind it. The Black people who moved to the northern industrial areas had the opportunity to receive good education, becoming the backbone of the automobile and other manufacturing industries, which made great contributions to the industrial development of the northern states. Still to this day, good school districts are an important factor for Chinese parents considering where to settle. The three children participated in the “vote with one’s feet” movement and became the pioneers of leaving discriminatory schools to go to different ones.

In the second year, Katie went to her brother-in-law’s house to see her children. After months of neglect and without the care of their mother, the three children were all pale and thin. The girls had unruly hair, the skin on their hands was chafed and dirty, and holes were worn out on the soles of their shoes. Without saying anything, Katie packed up their things and got on the next train headed for the south.

Unremitting struggle

In 1925, Attorney Brewer’s attention turned to helping Black folks who suffered from judicial injustice, and the Lum family lost their case in court. At this time, Chinese man J. K. Young extended a helping hand. Young turned out to be a successful businessman. He opened a grocery store in Tunika, south of Memphis. His ancestors were said to be one of the first Chinese folk to immigrate to the Mississippi Delta. He mastered English, familiarized himself with the culture of the Delta region, and often acted as a translator and intermediary in business contacts between Chinese and white people. He knew the Lum family and had been closely following the development of their case. When Attorney Brewer left, he volunteered to write a letter to the Federal Supreme Court as Gong Lum’s legal representative to request a trial. He also said that as Gong Lum’s legal representative, he would appear in court to debate. Then he wrote to Brewer and his assistants, emphasizing the importance of this case not only to the Lum family but to all Chinese people. He asked them to continue representing the Lum family during the Supreme Court’s appeal. The defendant was still the school board represented by Rice.

Bruce referred the case to James Flowers, the attorney who was the president of the Mississippi State Bar at the time. After graduating from law school, Flowers had been working for a railway company and had neither experience nor interest in court trials. The key legal premise for the Lum case was the equal protection clause as stated in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, but he had never been involved in any Fourteenth Amendment cases, so his knowledge was limited. Flowers refrained from appearing in court, but he did send his argument to the Supreme Court in writing. His core argument was that Martha was a Chinese person born in the United States, and that the only reason she was expelled from the Rosedale School was that she was not white and was being discriminated against for being “colored.” This violated state law. The equality required by the Fourteenth Amendment meant that Mississippi must provide Martha with the accessibility to schools that white children had access to. As for the segregation under Mississippi state law, he neglected to mention that in his argument [7].

On November 21, 1927, Supreme Court Justice William H. Taft issued a verdict unanimously passed by nine judges. They believed that the key issue in the case was whether a child of Chinese descent born in the United States could only attend schools for the “colored,” and whether or not that deprived her of equal protection. Tufts’ judgment stated that Mississippi had the right to determine the way to provide her with public education, which meant that the state could prohibit Martha from going to “white” schools. Tufts’ statement specifically cited the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896 (Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537 (1896)) [8]. In its judgement on this case, the Supreme Court ruled that as long as states can provide similar facilities for different races, they can implement segregation policies in regards to these facilities. This flawed principle was known as “separate but equal.”

The Supreme Court concluded that, “Most of the cases cited arose, it is true, over the establishment of separate schools as between white pupils and black pupils, but we can not think that the question is any different or that any different result can be reached, assuming the cases above cited to be rightly decided, where the issue is as between white pupils and the pupils of the yellow races. The decision is within the discretion of the state in regulating its public schools and does not conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.”

With this judgment, The US Supreme Court displayed its obvious support of segregation. Not only that, they also placed the right to determine a person’s race within the jurisdiction of a state. From then on, states under the rule of white racists could deprive a child of equal opportunities for education on the grounds of race. Within a few days, all major newspapers across the country published the results of the case. For more than 50 years after 1896, the Supreme Court continued to support “separate but equal.” Did they really not understand that there was no such thing as “separate but equal?” Ask a white person if they would like to trade places with a person of color during this time of segregation. Of course not.

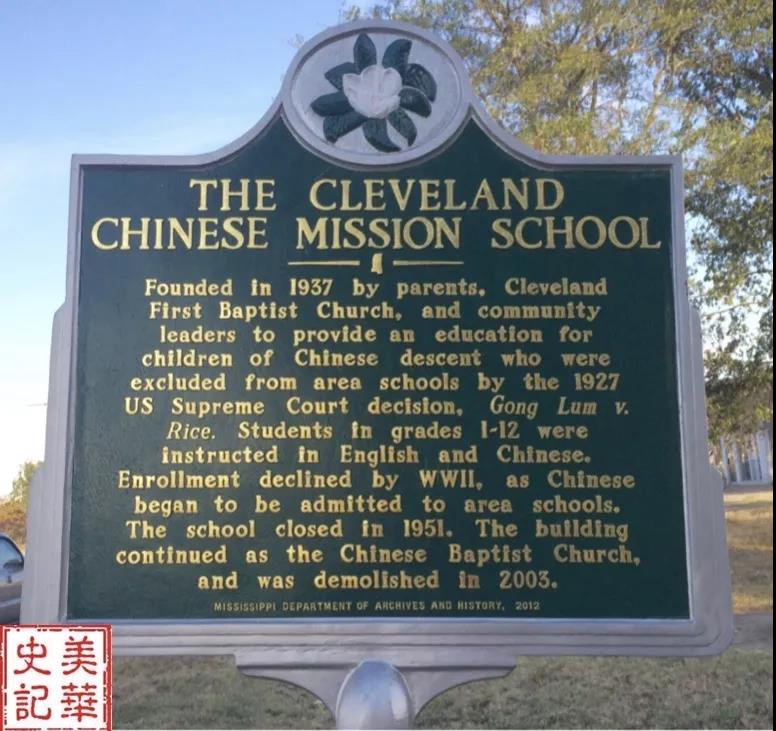

The Chinese representatives in the Delta tried their best to resist this policy, but failed. Since then, their children lost the opportunity to receive education in public schools. However, the Chinese tried once more in 1936 to fight against their discrimination by raising funds. They used the donations from Chinese businesses across the country to build the first Chinese Mission School in Cleveland. The local Baptist Church raised money to build a two-story schoolhouse which accepted Chinese students from various villages and towns [10].

Picture 6: A Chinese school student under segregation policies in Bolivar County in 1938, source: https://abagond.files.wordpress.com

Picture 7: Commemorative nameplate for the Cleveland Chinese Mission School, taken by the author in 2018

Turbulent times

The day the Lum family lost their case was a dark time. After losing the case in the Mississippi Supreme Court, Katie no longer participated in any activities related to white people. Although she was a Christian since childhood, she withdrew from the white church and even stopped talking to white people. It was a turbulent period, but Katie stood tall throughout it all. Gong Lum focused on raising the family, and Katie continued to fight for the education of her children. She found a white school in Elaine, Arkansas, on the other side of the Mississippi River that was willing to accept her children. Although the school building was old and the teachers were not as good as those of the new Rosedale School, it was still much better than the shack of a school provided by Mississippi for the “colored.” Gong Lum left Rosedale with his family and moved to Wabash, six miles from the school, and opened a small grocery store. Wabash was a small railway station in the middle of a large cotton field, with farmers’ huts scattered around. There was no running water there, and firewood was used for cooking and heat. Due to the small population, the grocery store could not sustain business. Katie worked from dawn to dusk to make and sell bread to support her family. Despite the difficulties, the Lum family held a glimmer of hope in their hearts. When the verdict by the Supreme Court was announced, Katie knew that they had lost everything forever; they lost not only the spacious store built by the couple over many years, but they also lost their dream home. After more than a decade of struggle, the family returned to poverty.

Persistence leads to success

Nevertheless, the Lum family still did everything in their power to support the education of their children. In 1933, Berta and Martha both graduated from high school, and Martha entered the teacher training program at Arkansas State University. After the start of World War II, the sisters moved to California to assemble bombers in the Long Beach arsenal. In 1940, their younger brother joined the army as a medical aid. In 1943, he was dispatched to work in the US Army Field Hospital in Yunnan Province, China [12].

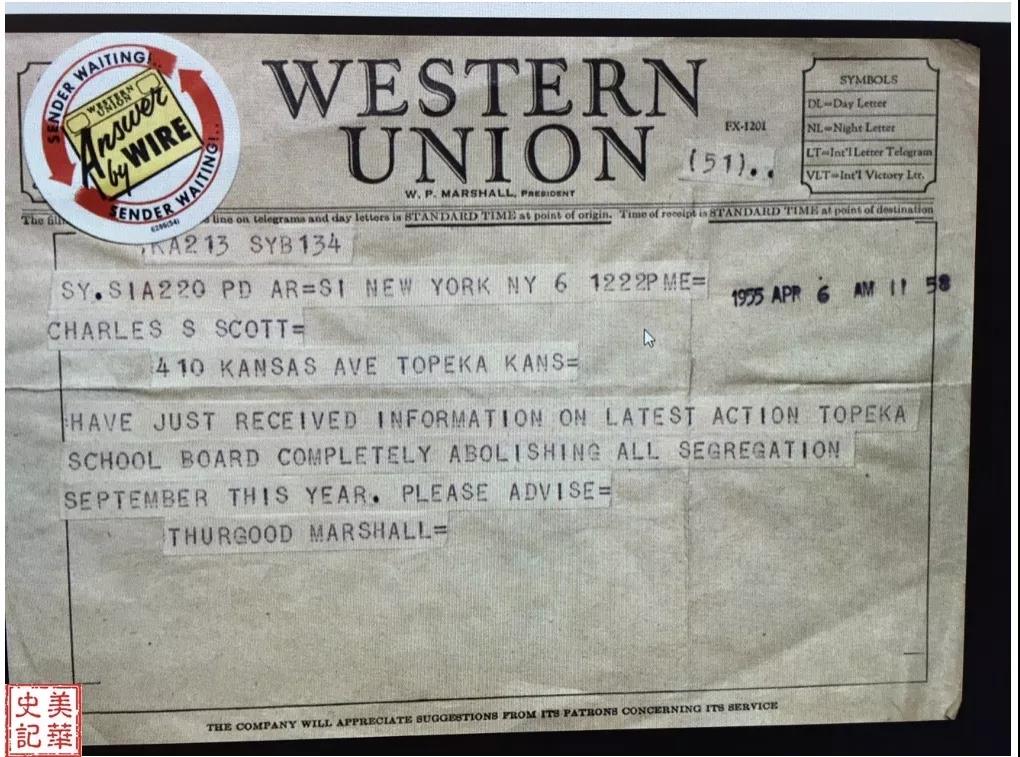

In the arduous struggle against racial discrimination and the defense of equal rights granted by the Constitution, the resistance and sacrifices made by the Lum family was the first wave of change. After Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483 (1954)) appealed to the Supreme Court in 1954, circumstances finally improved. In this milestone judgment, the Supreme Court ruled that even if the teachers of black and white schools have the same teaching ability, the segregation system itself causes harm to Black students and therefore violates the Constitution. The Supreme Court overturned the system of segregation that was upheld by the Plessy v. Ferguson case. This judgment also overturned the 1927 verdict in the case of Lum v. Rice, which was based on the principle of segregation. The Lum family finally witnessed the collapse of the racial barrier that they had been fighting for years.

Picture 8: The telegram sent by Marshall after winning the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education case Source: https://mediarichlearning.com/brown-v-board-of-education/

Katie’s story proves that the Chinese are not passersby, coming and going without fighting for change. Chinese people’s struggle for equal rights, including equal access to education, has always been an important part of the struggle between prejudice and justice in American history. The Chinese were not only the beneficiaries of equal protection, but also fighters against inequality and contributors of the abolition of segregation. Today, countless Chinese and other ethnic minorities continue to fight for equal rights, not only in education, in the workplace, but also in all aspects of life. Katie magnified her voice against injustice, and did not hesitate to fight alone. The persistence she demonstrated to achieve her goals is still an inspiration to us today.

Picture 9: The Lum family, see Adrienne Berard, Water Tossing Boulders: How a Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South

Sources and Citations:

- https://www.courtlistener.com/

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members.aspx

- Adrienne Berard, Water Tossing Boulders: How a Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South, (Beacon Press, Boston 2016), Chapter III

- Adrienne Berard, 2016: Chapter IV

- Greek Rice Jr. and I. J. Brocato, Clarksdale Register, October 13, 1924

- Adrienne Berard, 2016: Chapter VI

- Ibid, Chapter IX

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

- https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/101145/gong-lum-v-rice/

- Robert Seto Quan, Lotus Among Magnolias, (University of Mississippi, Jackson 1982), 47

- Adrienne Berard, 2016: Chapter X

- Ibid, Afterword

Pingback: Historical Record of Chinese Americans | Chinese Americans Challenging the “Racial Quota” – 亚太传统月/AAPI Heritage Month

Pingback: White Paper: National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – 美华史记