Author: Xin Su

Translator: Michelle X. Li

ABSTRACT

In 1994, a lawsuit was filed by the Asian American Legal Foundation against the San Francisco Unified School District (Ho v. San Francisco Unified School District), challenging the use of a “racial quota” to restrict the school admission of Chinese American students. This case successfully ended the practice of applying a “racial quota” in student admissions to K-12 schools. In accordance with this ruling, the San Francisco Unified School District adopted the “diversity index” instead of the “racial quota” in 2001.

Introduction

As early as 1850, Chinese immigrants came to California chasing the dream of the Gold Rush. At that time, they were willing to take any kind of job, from building railways to fishing to running small businesses to farming, and so on. In addition, they lived a frugal life and were honest and hardworking. As a result, they soon won the competition over local whites in the labor market. In the south, they were favored by many plantation owners, and signed contracts to work on the plantations. They worked hard in the arduous cotton plantations and gradually replaced the former slaves. During these early years, the Chinese immigrants managed to find their living space in the crevices of races; however, they did not have any educational resources. The California School Law promulgated in 1870 stipulated that only whites qualified for public education, while African Americans and Indians could receive segregated education sponsored by the state. Unfortunately, the Chinese were the only ethnic group who were obligated to pay taxes, but had no right and no access to any education resources. During 1884-1885, a Chinese family, Joseph Tape and Mary Tape, hired a lawyer and sued the San Francisco Board of Education, California (Tape v. Hurley), starting the fight for equal rights in public education for Chinese Americans. Because of this lawsuit’s victory, the Chinese children obtained their right to receive public education in the United States. Since then, generations of Chinese have been fighting unremittingly for equal education rights. With the arrival of Chinese immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong in the United States from 1950 to 1960, the number of Chinese in the United States reached its second wave of growth. Since the 1980s, with China’s reform and opening up to the outside world, Chinese immigrants from mainland China have continued to arrive in the United States, forming the third wave of growth and expanding the size of the Chinese American community. The new Chinese immigrants are different from their ancestor immigrants a hundred years ago. Due to the US immigration policy, the second and third waves of immigrants are mainly skilled immigrants. The vast majority of them are scholars and high-tech professionals who have studied in the United States with an advanced degree of education. Coupled with their natural hard-working attitude, these new Chinese immigrants are very successful and young talents are emerging in every field. Meanwhile, they are able to provide more resources for their children’s education. Traditionally, Chinese people place a great deal of importance in the education of the next generation, and almost every Chinese family wants their children to enter a good college. However, this desire has hit a roadblock due to the “racial quota” admission system.

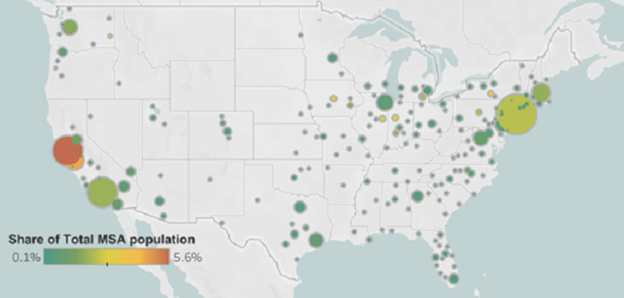

Note: Pooled 2014-18 ACS data were used to get statistically valid estimates at the metropolitan statistical-area level for smaller-population geographies. Source: MPI tabulation of data from U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2014-18 ACS.

Figure 1: Chinese immigrants mostly live in New York City, San Francisco and Los Angeles, accounting for approximately 43% of total Chinese immigrants. Data Source: 2014-18 ACS https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states/

1. Case Review: Asian American Legal Foundation vs. San Francisco Unified School District

The San Francisco Unified School District is the seventh-biggest school district in California. The entire school district has a class size of more than 57,000 students each year. Over the years, the school district’s educational philosophy has always included “social justice” and “diversity driven” as the school’s core values [1].

Figure 2: SFUSD District Mission Statement: Our core values guide us through the challenges Source: https://www.sfusd.edu/about/our-mission-and-vision/our-core-values

However, the allocation of local educational resources has always been a complicated issue. In 1978, anti-segregation activists (NAACP: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) filed a class action lawsuit against the San Francisco Unified School District, for engaging in racially discriminatory practices and maintaining a segregated school system in San Francisco. In 1983, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California signed a consent decree agreeing to the content of the lawsuit, requiring that no ethnic group could have an exclusive majority in the school, and an independent reviewer would submit an annual report regarding the district’s compliance with the consent decree [2, 3].

In order to promote racial diversity and reduce racial discrimination, the school district reformed its admission policy: students were initially divided into 9 ethnic groups, and then expanded to 13: American, American Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Hispanic/Latino Americans, Japanese, Koreans, whites, Arabs, Samoans, Southeast Asians, Middle Easterners, and other non-whites. Members of at least four of the groups were required to be present at each school; and no one group could represent more than 45 percent of the student body at any regular school or 40 percent at any alternative school [4].

Lowell High School, one of the best high schools in the United States, is a selective magnet school. It’s permitted to select students through a competition admission process, but it must comply with the requirement of no more than 40% of students of a single ethnic group. This upper limit mostly affected the Chinese students [2]. With a long history in San Francisco, over the years, Chinese Americans had become the city’s largest identifiable ethnic group, and the selective Lowell High School was naturally the dream school of the majority of Chinese students. However, in the process of student quota allocation in the San Francisco school district, a child who identified as Chinese, no matter how outstanding he was, was most likely to be “capped out” from entering Lowell High School and be forced to attend a non-chosen school that’s often far from his or her neighborhood because of the racial quota policy.

Figure 3: A diversified San Francisco Unified School District. Data Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUnxyMAXxGs

Therefore, in response to the ethnic quota admission policy, the Asian American Legal Foundation, on behalf of three Chinese children, filed a lawsuit against the San Francisco Unified School District in 1994 in the Northern District of California District Court (the Ho case). The three children represented in this case were Brian Ho, Patrick Wong, and Hillary Chen.

- Brian Ho, five years old at the time the lawsuit started. In 1994, he was turned away because the school had reached its quota for people of Chinese descent, and was assigned to a school in another community [4].

- Patrick Wong, then fourteen years old. When he applied for admission to Lowell High School, he was rejected because his index score was lower than the lowest score of the ethnic Chinese group. However, putting him in any other ethnic group, his score was high enough. The other two high schools also rejected him for the same reason. When he tried to apply for the fourth middle school, all the slots for people of Chinese descent were “filled”, however, there were still vacancies for applicants from other ethnic groups [4].

- Hillary Chen, then eight years old. In December 1993, she needed to transfer schools because her family moved, however, all three primary schools near her new home reached the highest quota for people of Chinese descent, so she was unable to transfer [4].

This lawsuit began an arduous struggle for five years.

On January 19, 1995, the court added as a defendant the San Francisco National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (SFNAACP) along with the original defendant, the San Francisco Unified School District. On March 8, 1996, the court approved the plaintiff as “all Chinese children eligible to enroll in the San Francisco Unified School District.” At first, the plaintiff’s motion was rejected by the District Court [5], then the Asian American Legal Foundation appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court, requesting that the school district’s racial assignment plan would have to be examined under strict scrutiny to ensure that there was no discrimination against Chinese American students. Both the District Court and the Ninth Circuit indicated that if the defendant was examined as requested, it would almost certainly fail [6]. Finally, the defendant agreed to a settlement. In 1999, Judge William Orrick announced to abolish the 1983 consent decree, stop using racial quotas in the admission process, and terminate all provisions of the decree before 2002 [7, 8]. Since then, members of the Asian American Legal Foundation have been carefully monitoring the student admission program used by the San Francisco Unified School District to ensure that students are no longer classified by race. Eventually, in 2001, the school district switched to the “Diversity Index” in replacement of “racial quotas” in admitting students [8].

2. The racial problem of “educational desegregation”

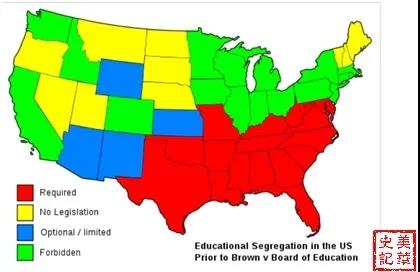

According to American historical records, before 1950, many states in the United States practiced racial segregation in education: African Americans were not allowed to go to the same schools as whites. In 1924, the Rosedale Consolidated School in Mississippi only accepted “Caucasian races” and did not accept Chinese children at all. A Chinese immigrant, Gong Lum, brought a lawsuit to the Supreme Court (Gong Lum, et al v. Rice et al, 275 US 78). Unfortunately, under the circumstance of that time, Lum lost the lawsuit and failed to change the situation of educational segregation. It was not until 1954 when the case of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483, 1954) was won that the segregation situation finally started to change.

Figure 4: Educational segregation in the United States prior to Brown v Board of Education of the City of Topeka. Picture source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_v._Board_of_Education

The case of Brown v. Board of Education of the City of Topeka began in 1951, when the public school district in Topeka, Kansas refused to let the daughter of a local African-American resident Oliver Brown attend a school near her home and asked her to ride a bus to a segregated African-American elementary school further away. The Browns and twelve other African-American families in similar situations filed a class action lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education in the U.S. Federal Court, claiming that the segregation policy in public schools was unconstitutional. This was the famous historic “Brown v. Topeka Board of Education” case and a landmark win at the U.S. Supreme Court. On May 17, 1954, the court ruled that segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution [9]. This ruling also rejected the 1927 judgment in the case of Lum v. Rice based on the legal basis of segregation. From that time on, the descendants of Chinese in the southern United States finally saw the light of desegregation.

Figure 5: Mrs. Nettie Hunt, sitting on the steps of the Supreme Court, holding a newspaper, explaining to her daughter Nikie the meaning of the Supreme Court’s decision banning school segregation. Picture source: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images.

Although the case of Brown v. Board of Education was victorious, the 14-page ruling did not provide any specific details on how to desegregate. In the following decades, all school districts across the country began to strictly enforce the mandatory desegregation order from the Federal Court. In the past ten or twenty years, more and more schools have begun to switch to voluntary integration policies to promote school diversity. The school’s voluntary integration policy is actually the legacy of Brown’s abolition of segregation. The original abolition of segregation in education had benefited the descendants of all Chinese in the United States. However, after the implementation of voluntary integration in the San Francisco Unified School District, the previously mentioned quota issue unexpectedly hit Chinese descendants.

In fact, for the majority of the 1970s, the definition of segregation was regarded as an issue between African Americans and whites. The San Francisco National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and its allies had always been actively working to correct the government’s racial discrimination against African American students [3]. However, driven by the voluntary integration, the San Francisco Unified School District adopted a “racial quota” policy. “When enrolling students, an upper limit was set for specific ethnic groups to achieve racial integration. The reason was to reduce racial discrimination. The key problem was that ethnic Chinese students were too concentrated in the San Francisco area. Coupled with the excellent academic performance of Chinese students, the school district’s racial quota policy directly had led to good schools (such as Lowell High School) that had much higher admission standards for Chinese students than any other ethnic group. This had caused widespread dissatisfaction among local Chinese communities.

When the San Francisco National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the school district were sitting at the negotiating table, teachers, Latinos and Asian Americans were excluded. All three groups filed lawsuits during the life of the Consent Decree demanding that they, too, be parties to the desegregation settlement. Obviously, the San Francisco National Association for the Advancement of Colored People failed to represent the interests of Asian Americans (Chinese) on this issue. Thus, there was a Chinese lawsuit in 1994 against the San Francisco National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the San Francisco Unified School District. This lawsuit caused tension between ethnic groups. Of course, both sides paid a political price, and finally reached a consensus. The judge decided in 1999 to abolish the racial upper limit of the 1983 consent decree and terminated all the provisions of the decree before 2002 [8].

In 2001, the school district adopted a “diversity index” policy when enrolling students. The “diversity index” included multiple indicators such as mother’s education level, student socioeconomic status, test scores, English proficiency. The purpose of using this “diversity index” policy was to help disadvantaged groups.

Since the implementation of the “Diversity Index”, Chinese and white students have been more dominant in the best schools in the area, while more African-American and Latino students were enrolled in the worst schools. By 2005, although the San Francisco Unified School District’s academic performance index ranked higher than other urban school districts, the performance scores of African-American students in San Francisco school district were still lower than those of African-American students in San Diego, Los Angeles, Long Beach, Sacramento and other places [3]. In the 2007-2008 school year, the proportion of Latin American students in the school district was 23.0%, African Americans accounted for 12.8%, Chinese Americans accounted for 31.4%, and other whites accounted for 9.8%. In the best Lincoln High School, Chinese students accounted for 51.1%; in Washington High School, Chinese students accounted for 30.3% to 31.4%, and African Americans accounted for only ~7% [2].

Critics claim that the San Francisco Unified School District’s “diversity index” admission policy has reduced the diversity in schools [2]. According to the demographic prediction, the Latin American and Chinese American population in San Francisco will continue to grow, while the number of whites and African Americans will continue to decline. The Chinese as a minority ethnic group has become a majority in San Francisco, and the education of Chinese children will face new challenges [2]

The San Francisco Unified School District has made arduous efforts for racial integration and school diversification. However, the problem is still unresolved, running cycles between segregation, de-segregation/integration, and re-segregation… In a report on student admissions and distribution policies, district leaders say “the trend of racial isolation and concentration of underserved students” cannot be reversed through student assignment alone [10].

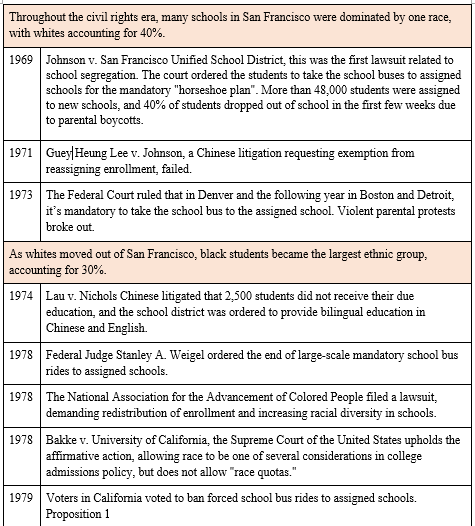

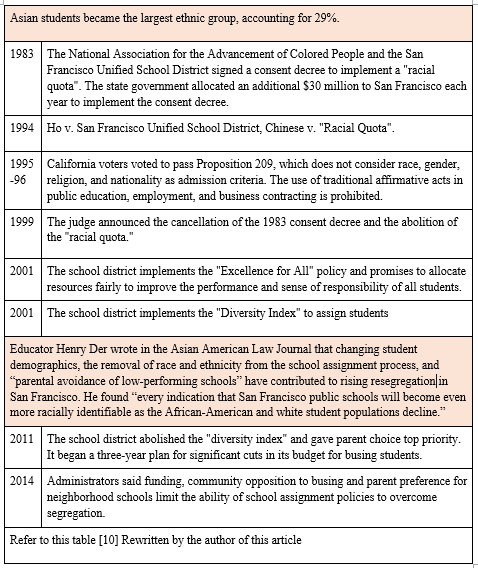

Table: San Francisco Unified School District has made strenuous efforts for racial integration and school diversification

3. Chinese Americans promoting fair common good

Let’s look back at the Guey Heung Lee lawsuit against Johnson in 1971 (404 U.S. 1515), which was a case at the U.S. Supreme Court related to desegregation in San Francisco schools. In 1971, the San Francisco Unified School District tried to redistribute students from segregated schools to other public schools, hoping to abolish the school’s systemic segregation.

The school district submitted a comprehensive desegregation plan that was approved by the district court. However, some Chinese parents protested and hoped that their children would continue to attend Asian schools. The reason was that Chinese students could learn Chinese culture in Asian schools, and they would lose this opportunity if they had to enroll in public schools. The District Court and the Ninth Circuit all rejected the lawsuit [11]. Cynthia Der analyzed in the article that one of the reasons why the court denied Guey Heung Lee’s appeal was that the Chinese only worried that their children would lose the opportunity to learn Chinese culture and language in the neighborhood schools. This was very different from Brown’s opposition to the educational segregation, Brown didn’t oppose to segregation just for African Americans [2]. Obviously, the reasons presented by the Chinese parents who opposed the school’s desegregation did not receive sympathy.

In an article analyzing the “racial quotas” case of the Asian American Legal Foundation’s lawsuit against the San Francisco Unified School District, Cynthia Der[2] stated that there are two options when an identity group seeks to rectify an injustice. One option is to pursue a remedy through litigation; the other option is to engage in broader coalition building with other identity groups around a social issue and “across difference.”

The Chinese Americans shall engage members from different ethnic backgrounds, help them understand the anxiety of the Chinese community, and work together to promote education reform for all. Of course, it cannot be accomplished overnight, but it should be the path forward that the Chinese Americans people shall take.

Justice has to be universal, and it cannot only solve the problems and predicaments for some people, while leaving others behind. The goal of Chinese Americans promoting justice is equal rights in education for the offspring of Chinese people and to achieve a broader right to equal access to education in the whole society. This is a fair common good.

4. A history worth remembering: Chinese protest the “racial quota” policy in education

The ideal of the Chinese is to build a multi-ethnic, indivisible, equal and diversified society. All ethnic groups and members participate in the country’s civic life. Fighting against discrimination in education is a key part in the pursuit of social justice and has to be viewed from a multi-dimensional and multi-layered perspective.

So, are Chinese Americans discriminated against in education?

On the surface, it seems that many Chinese students have entered their dream schools and enjoy a lot of educational resources, so the protest from the Chinese community may make them look like they are just asking for more. However, what’s not revealed from beneath this surface are invisible hardships the Chinese students have and great efforts they made. The outstanding academic performance of Chinese students does not fall out of thin air; it’s a result of ideals and actions supported by all members of a strong family with perseverance. At the same time, the Chinese students have devoted tremendous effort into their academic work and extracurriculars such as tutoring, community service and social involvement since a very young age.

Patrick Wong, one of the parties involved in the above-mentioned case, lost to students from other ethnic groups with the same score and couldn’t attend his dream school Lowell High School just because his index score was lower than his Chinese Americans peer students. What does this fact imply? Philosopher Aristotle once said, “Justice means to give people what they are due, what they deserve. Giving the flute to the best flute player, regardless of wealth, nobility, physical beauty, etc. [12].” Similarly, students with high index scores should have the opportunity to enter their ideal school, and should not be devalued due to ethnic factors. The influence of human factors in allocating resources according to ethnicity has put some people in a disadvantageous position, which obviously violates the principle of justice. There is essentially no difference between using “racial quotas” to exclude or to benefit certain groups of people. It is just a different manifestation of discrimination. The school admission policy using “racial quotas” violates the fundamental right that the U.S. Constitution guarantees: “everyone is equally protected by the law”.

Figure 6. Philosopher Aristotle (384 BC to 322 BC) influenced the entire world civilization. One of his classic sayings is “Justice is not a part of virtue, but the whole virtue; on the contrary, injustice is not a part of evil, but the whole evil.”

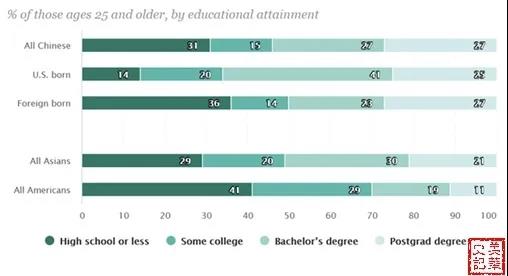

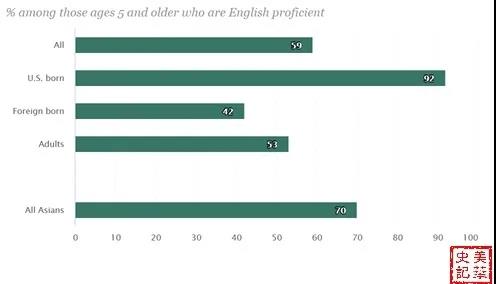

On the other hand, since the Chinese have been put on the shackles of being “model minorities”, this stereotype has really played down the efforts the Chinese put in and concealed the plight of a large number of Chinese living in poverty and speaking no English (see the picture below). In fact, not every Chinese offspring does not need help in their studies. The rights of these Chinese cannot be ignored. School admissions under “racial quotas” cannot really help disadvantaged groups (Chinese or other ethnic groups) who need help.

Figure 7: Educational level of Chinese Americans in 2015: 54% with a college degree or above (higher than the national average of30%); 31% of Chinese Americans have only a high school education. Picture source: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/chart/educational-attainment-of-chinese-population-in-the-u-s/

Figure 8. In 2015, only 59% of Chinese Americans were fluent in English. Picture source: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/chart/english-proficiency-of-chinese-population-in-the-u-s/

As a minority group, Chinese Americans have received varying degrees of unfair treatment in many fields such as education, employment, and medical care. The current discrimination against Chinese Americans has deep roots. There has been a long string of events that overlook and disregarded. Every ethnicity has the righteous responsibility to its own group, and also certain obligations to other ethnic groups. In an inclusive and interactive political process, social justice will be enhanced when different ethnic groups challenge each other. On the other hand, rejecting or putting aside rights or justice will not help promote social progress.

Reference:

- San Francisco Unified School District Website https://www.sfusd.edu/about/our-mission-and-vision/our-core-values

- Cynthia Der. A Chinese American Seat at the Table: Examining Race in the San Francisco Unified School District. 1077-1114.

- Rand Quinn, Excerpt From Class Action: Desegregation and Diversity in San Francisco Schools: Desegregating San Francisco Schools. https://www.socialpolicy.org/latest-issues/1041-excerpt-from-class-action-desegregation-and-diversity-in-san-francisco-schools-desegregating-san-francisco-schools.html

- The Ho v. SFUSD Case – The Battle to End Racial Discrimination in San Francisco Schools. https://www.asianamericanlegal.com/the-ho-v-sfusd-case-the-battle-to-end-racial-discrimination-in-san-francisco-schools/

- HO v. SAN FRANCISCO UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT. https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-9th-circuit/1455083.html

- Ho v. San Francisco Unified Sch. Dist., 147 F.3d 854 (9th Cir. 1998)

- Ho v. San Francisco Unified Sch. Dist.,59 F. Supp. 2d 1021 (N.D. Cal. 1999).

- Kathy Emery. A Brief History of the San Francisco Unified School District and the Consent Decree http://www.educationanddemocracy.org/SF/Brief_history_SF.htm

- History.com Editors, Brown v. Board of Education. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka. 2020

- Sanne Bergh and Paul Lorgerie. As Courts Flip-Flopped on School Integration, Diversity Has Remained Elusive.an Francisco Public Press. Feb 5 2015 – 5:26pm https://sfpublicpress.org/news/2015-02/as-courts-flip-flopped-on-school-integration-diversity-has-remained-elusive

- Ted Jou. Grutter Goes Back to School: Revisiting Ho v. San Francisco Unified School District. 2005

- Michael J. Sandel. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2010.