Author: Qian Huang

Translator: Audrey M. Jiang

Introduction

In 1879 there were two Chinese Americans in the US Navy’s Arctic Expedition: Charles Tong Sing (1859-?) and Ah Sam (?-1881). They were the first Chinese Americans to explore the Arctic.

A Navigator’s Dream: A Route to the Arctic

Human explorers to the Arctic have long considered the journey there an extraordinary test of courage and endurance. The Arctic is an exceedingly unforgiving environment: No solid land, temperatures that regularly dip below 0, and no humans for miles in case anything goes wrong. Despite this, humans have and continue to explore the Arctic. The first American expedition to the Arctic was in 1860, led by Isaac Israel Hayes (1832-1881), whom after returning wrote a book claiming that he had found an ice-free route to the Arctic. At the time many navigators and explorers believed that because of the Kuroshio Current, warm water flowing towards the Bering Strait would form an ice-free route to the Arctic, termed the “Open Polar Sea.” [1]

Between the 20-year period from 1860 to 1880, an Arctic expedition set off virtually every year. These explorers all hoped that they would be the hero to find a route to the Arctic.

1879: Charles Tong Sing, Ah Sam, and Ah Sing, Board the Arctic Expedition Ship

In 1879 New York publisher and business tycoon James Gordon Bennett Jr. and the US Navy decided to sponsor an Arctic Expedition with the hopes of passing through the Bering Strait and reaching the Arctic through the fabled “Open Polar Sea.”

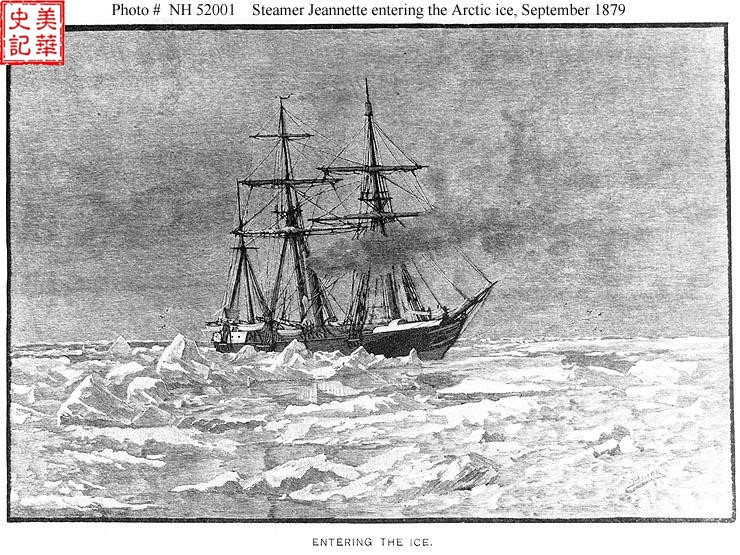

For this purpose they bought a ship which they named Jeannette. Naval officer George W. DeLong (1844-1881) assumed the position of captain and leader of the expedition. The formal name of this expedition was the U.S. Arctic Expedition.

Figure 1, the Jeannette. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeannette_expedition#/media/File:USS_Jeannette;h52199.jpg

Figure 2, Lieutenant Commander George W. DeLong. Naval History and Heritage Command.

On Tuesday, July 8, 1879, the Jeannette set off on its maiden voyage. As it passed through the Golden Gate, naval artillery fired an 11-gun salute. The Jeannette raised its flag and sounded its whistles in response to the cannons. The 33-member crew, including the three Chinese Americans onboard, carried the weight of the world’s hopes, yet they still proceeded with optimism and courage, the breeze streaming off the sea and the crowds of people waving on the pier.

At the beginning of the journey, because the Jeannette was weighed down with coal, it could only move slowly. In the first 35 days, they only traveled about 3000 miles. Despite this, the crew was in good spirits—Captain DeLong even likened them to one big family. In the evenings everybody would gather to play the accordion, sing songs, and tell jokes. The crew seemed the perfect picture of America in the Gilded Age: self-reliant, independent, persevering. As well as embodying the values of America, the crew was also diverse, representing the immigrant dream– there were Germans, two Danish people, two Irishmen, one Finn, one Scot, one Norwegian, one Russian, some French-Americans, Dutch-Americans, Scotch-Irish people, and three Chinese people.

Charles Tong Sing and Ah Sam, two of the Chinese members of the crew, were specifically handpicked by DeLong from the streets of the San Francisco Chinatown to be cooks and cabin stewards.

DeLong had high expectations for his cooks, as the food brought on the Arctic Expedition had special preparation requirements and so needed highly capable cooks. The cooks would have to be able to find wood and start a fire in the wilderness, and walk long distances. The 19-year-old Charles Tong Sing stood at a height of 175 cm (about 5’9”), and at the time had been working as a chef at an inn in the area. DeLong took care to explain to him the dangers of the expedition. Tong Sing, however, did not even know what the Arctic was, but knew that the Navy pay was much better than what he had gotten at the inn. Soon afterwards, Tong Sing accepted the offer to join the Arctic Expedition.

DeLong was fond of his two Chinese cooks, and even more fond of Ah Sam’s cooking. Tong Sing and Ah Sam were also always in good cheer, and in the eyes of the rest of the expedition, they seemed like the type of people that nothing could wear down.

Onboard there was a third Chinese American named Ah Sing, who served as an orderly. Ah Sing did not understand English, and was a perpetually nervous, uncoordinated figure. He would often break plates and cups, spill water, or generally mess up the state of things. The other two Chinese Americans often scolded him, but to no avail. Chief engineer Melville disliked Ah Sing intensely, to which DeLong responded that if he ever gave Melville the order to shoot him, he could.

Soon enough the wind picked up, and the waves began to get bigger and bigger. Ah Sing became seriously seasick. DeLong described Ah Sing as “just like a newly-resurrected corpse, like he was his own shadow, his braid blown into a mess, I’m afraid he cannot live any longer.”

On August 27, as the Jeannette was getting ready to pass through the Bering Strait, DeLong decided to let Ah Sing return to the mainland on the last ship providing provisions and fuel. [2]

When Ah Sing left, DeLong found himself without an orderly. As a result, DeLong had Tong Sing take on Ah Sing’s job, promising to pay him twice as much for doing so.

Frozen in Place for 21 Months

Two months after their departure, Jeannette entered the Arctic Circle. Events quickly went for a downturn after that, as they found themselves surrounded by ice for the entirety of September and October, with no way out.

Figure 3, Jeanette surrounded by the Arctic ice. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Up until they were completely frozen, the crew attempted to break the ice using saws and a variety of other tools. However, their efforts soon proved futile, as the ice inevitably froze faster than they could break it. With no other options except to wait for summer, they let the boat drift, at the mercy of the wind and water.

The long nights, combined with their seemingly bleak prospects, greatly dampened the morale on the ship. Seeing this, Tong Sing and Ah Sam took it upon themselves to provide some entertainment, which included flying kites. Tong Sing also took this opportunity to teach himself English.

Six months after leaving San Francisco, Christmas came around, during which Tong Sing and Ah Sam cooked up a sumptuous feast: hot soup, spicy salmon, turkey, ham, sweets, and beer, as well as cigars. When presented with this elaborate holiday banquet, the crew actually teared up. [3]

1880: Taking on Water, Disease, and the Escape from the Arctic

On New Year’s Day the crew was putting on a show, in which Tong Sing and Ah Sam recited a song in Cantonese. It was thus, in a flurry of joy and song, that the Jeannette passed into the year 1880.

In June of 1880, the bottom of the ship began to take on water, which became more and more worrying. According to DeLong’s estimation, the ship took on 4,874 gallons of water per day. But what was more concerning was the fact that 7 people had come down with a mysterious illness, which exhibited the following symptoms: listlessness, insomnia, inability to keep food down, memory loss, metallic tastes on the tongue, abdominal pain, and blood in urine.

The two that were the most heavily afflicted were Tong Sing and Newcomb. DeLong recalled that both of them had enjoyed eating tomatoes. It turns out that the illness was lead poisoning, caused by the lead from the outside of containers reacting with the tomatoes’ acidity, causing the lead to dissolve into the tomatoes. They successfully averted one crisis with this discovery, preventing many more serious possibilities– like fainting, seizures, kidney failure, and eventually death.

Henrietta

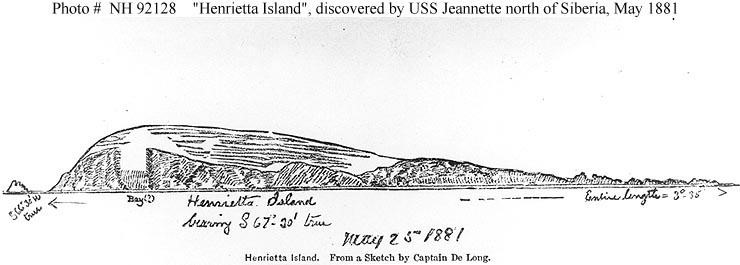

On June 5th, 1880, DeLong’s longtime observation and speculation finally gave rise to an answer: on the distant horizon there appeared a small island, now called Henrietta Island.

Figure 4,DeLong’s sketch of Henrietta Island. Naval History and Heritage Command.

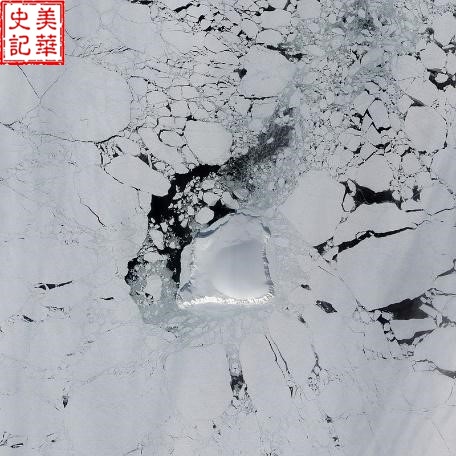

Figure 5,Henrietta Island satellite photo. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henrietta_Island#/media/File:Henrietta_Island,_Russia.jpg

“Thank God, we have set foot on a newly discovered piece of Earth…” in his surprise, DeLong fell on the stairs to the deck and injured his head, blood streaming down his face. Upon seeing this sight, Ah Sam exclaimed “Ah, a big big hole!” [4]

On the less optimistic side, however, Henrietta Island was lacking in resources: No animals to hunt, wood to burn, or a place to anchor their ship.

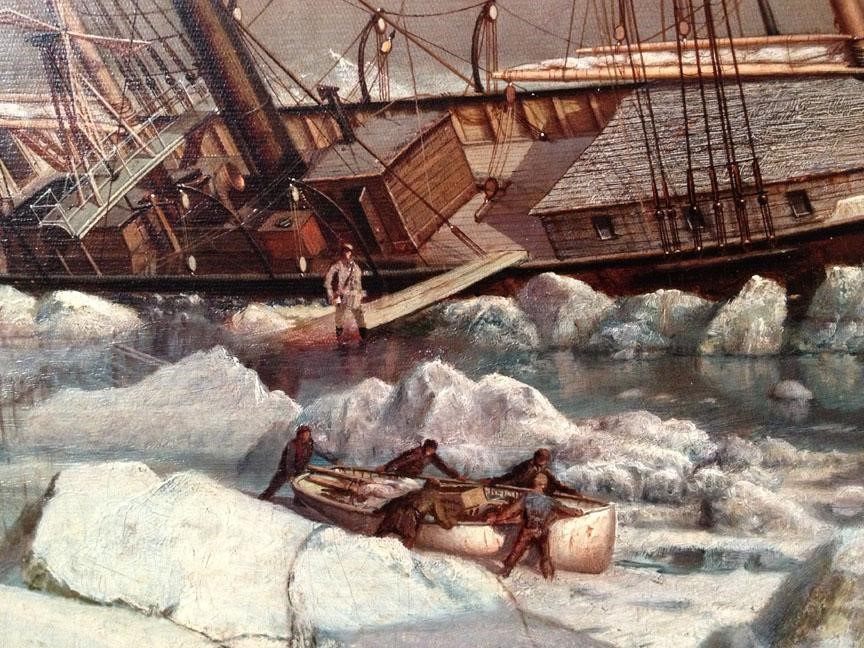

The Loss of Jeannette

By this time it was already June and the ice had started to melt. The Jeannette, though, was still being pressed in by ice on all sides, slowly drifting.

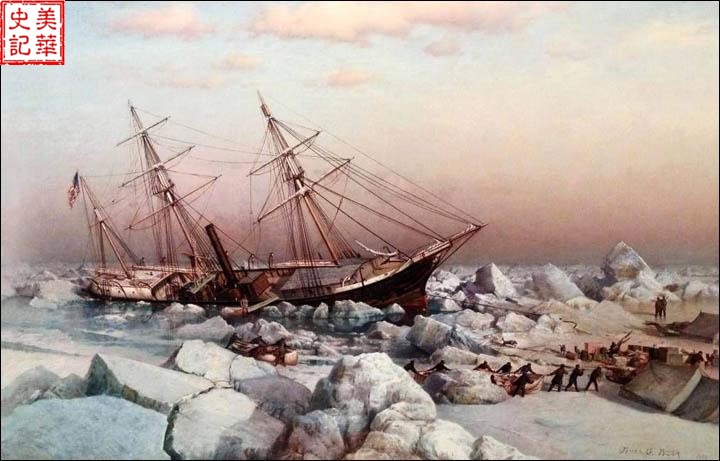

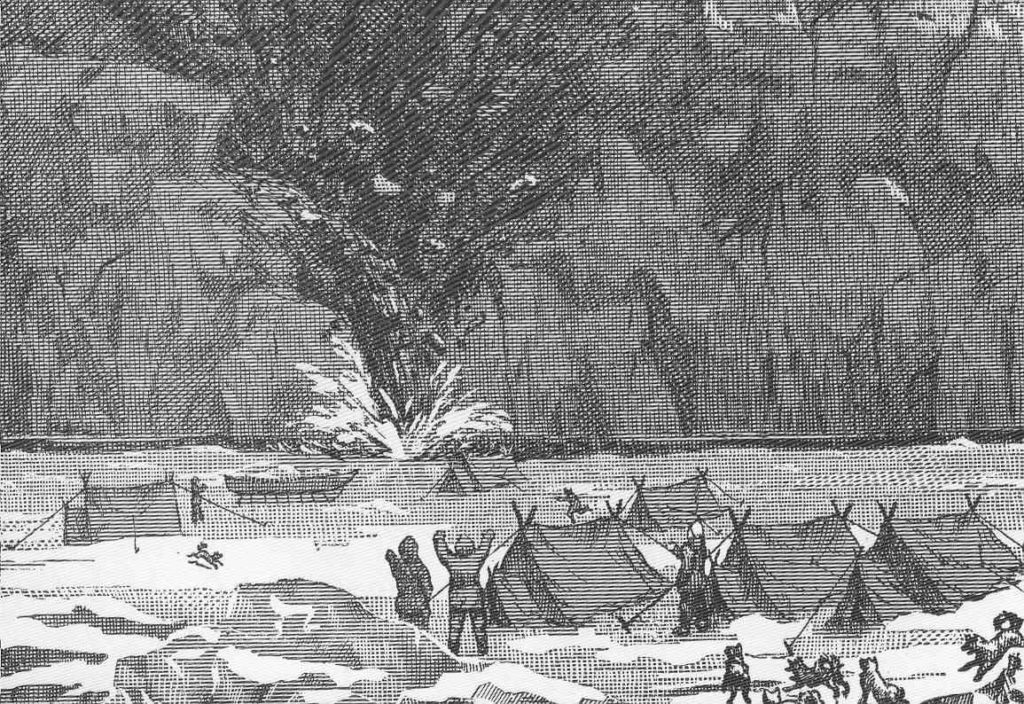

The most terrifying possibility finally happened on June 11, 1881: The floating ice pierced through Jeannette’s hull—water rushed in, causing her to tilt. Some of the crew managed to get three lifeboats, while the others scrambled to save their essential supplies.

Figure 6, Escaping the Jeannette. https://www.vallejogallery.com/item_mobile.php?page=item_page&id=281

Figure 7, the crew scrambling to get their essential supplies before Jeannette sinks. https://www.vallejogallery.com/pics/tyler_jeanette_07_off_midship_detail_web.jpg

That night, the 33 crew members stood on the ice, watching what had been their home drift farther and farther away. The cold, barren expanse before them was charged full of despair, yet it had also suddenly become the situation immediately at hand: They had been trapped in the frozen sea for 22 months with nowhere to run. Now they were engaged in a struggle of epic proportions– this time for their lives. [5]

Figure 8,the crew members watching Jeannette sinking. https://www.soundingsonline.com/.image/c_limit%2Ccs_srgb%2Cq_auto:good%2Cw_255/MTQ3ODk1MzE1MjI5NTE3NzQ2/the-jeannettes-sinking-was-dramatically-portrayed-by-the-popular-french-artist-george-louis-poilleux.webp

The Battle for Their Lives

At the outset, DeLong and the crew had a 1600 km journey before them, through a hostile and unfamiliar environment. They brought 8 tons of equipment and food, trudging 12 hours each day across the icy terrain, risking snow blindness and rotted feet every step of the way. The mental strain quickly wore down some members of the crew, and even some the dogs started acting abnormally. Even worse was their lack of a freshwater water source, meaning they had to drink more than a month of straight saltwater.

Figure 9,the crew members pushing a lifeboat. https://siberiantimes.com/PICTURES/OTHERS/Schooner-Jeannette-rescue/inside_crew_with_boats.jpg

After walking for more than 40 days, the crew members reached the boundary of life and death, with all their medical supplies gone.

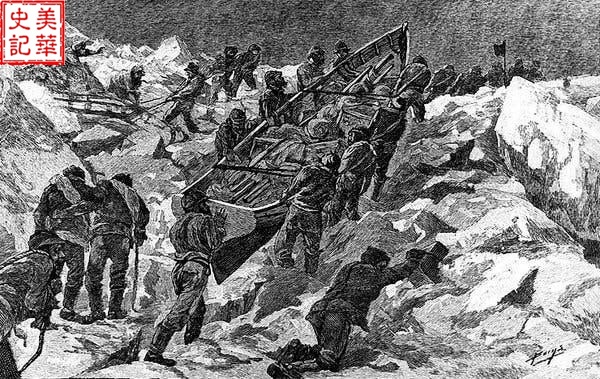

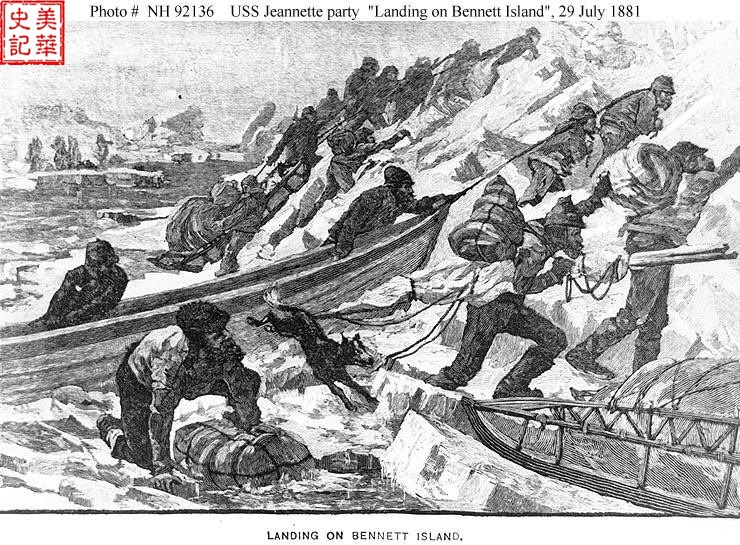

Discovering New Territory

On July 29, another island appeared on the horizon. DeLong, raising the American flag, eagerly claimed the island for the United States. The island was named after their sponsor, Bennett. This was the first time in two years that any of them had set foot on solid land—the surgeon, Ambler, expressed jubilation at the idea of returning to the realm of human and Earth interaction.

Figure 10,the crew landing on Bennett Island. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Figure 11, the expedition claiming Bennett Island for the United States. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Before dawn, the expedition members were jolted awake by a deep rumbling within the Earth. In the weak morning light, they could dimly make out the shape of a collapsed mountainside. No one was seriously harmed by the landslide, but the grit and dust from the landslide did drift over to their campsite, causing a mass choking fit. Stuck in the middle of nowhere in such a situation, the landslide couldn’t help but seem like a bad omen. DeLong wrote of the event in his journal, saying “We came prepared, so nothing can scare us off now.”

Figure 12, the expedition encountering a landslide. Naval History and Heritage Command.

DeLong’s party separated into two groups to explore the island, which had high plains, volcanoes, glaciers, capes,and coal deposits in rock piles. The expedition members also collected many geological specimens, such as opal, amethyst, lava that had cooled into rocks, mammal bones, and elk antlers. There were many forms of wildlife on the island as well, like bears, foxes, and rabbits.

The abundance of wildlife on the island meant that the expedition had a stable food source. One time, Collins asked the captain for permission to go hunting, and an hour after, came back with a sea lion. Ecstatic, they skinned the sea lion and cut the meat into pieces, and cooked the meat for a meal. It had been a long time since most of them had eaten fresh meat, so even just sea lion meat seemed like a bite of heaven. Even better, they caught a walrus a few days after!

Figure 13, satellite photo of Bennett Island, currently Russian territory. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Bennett_-_Landsat.jpg?1602468705167

In these 8 days the expedition members took time to recuperate, fix their lifeboats, survey the land, and collect specimens. Before hitting the road again, DeLong decided to dispose of the sled dogs, as the dogs couldn’t fit in the boats. 11 of the sickest and/or weakest dogs were shot and then thrown into the sea.

On August 6, they said goodbye to the island which had provided them with freshwater and a safe place to rest. The expedition members, pulling their lifeboats along, trudged step by step until they reached open waters. Only then could they put down the boats and start rowing.

Figure 14,the crew in their lifeboats. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Faddeyevsky Peninsula

On August 30, 1881, the expedition reached the Faddeyevsky Peninsula. The peninsula is part of the Anzhu Islands, and was first settled by a fur trader called Faddeyevsky, whom the island is named after. Ah Sam, upon setting foot on the island, found a stream near the cabin, which was great news to the expedition, who had been drinking saltwater for days. With a profound sense of relief, the expedition members stripped off their frozen deerskin coats to lay down to a night of quiet, uneventful sleep, without the tossing of waves and the howl of wind.

Figure 15,the route the expedition took, from Jeannette’s shipwreck to the Lena Delta. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeannette_expedition#/media/File:Jeannette_crew_course_map.png

On September 4, their escape route once again froze into ice. The crew members were left with no choice but to drag their boats with them. Ambler, the surgeon, said: “I am already completely frozen numb, with no idea if I’m feeling pain or cold. You have all suffered the same as me, yet nobody has even once complained.” [6]

At this time there were still about 100 miles away from Siberia.

The Last Gale

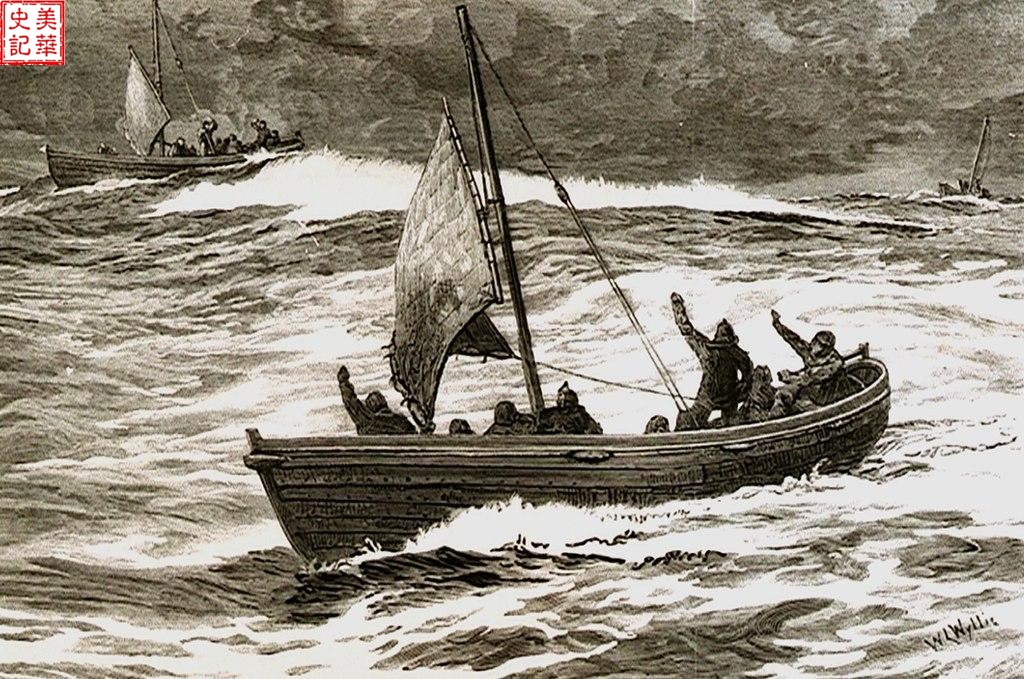

By September 12, 1881, the 33-member crew had been fighting for their lives together for 3 months on the icy seas. In two more days they could hope to reach Siberia—but then disaster struck. A sudden gale blew apart the three lifeboats.

Figure 16,September 12, 1881, a gale separates the three lifeboats.

On Melville’s lifeboat, they had to rely on the sun and stars to find a route. Waves also crashed relentlessly into the lifeboats, threatening to capsize them. Tong Sing worked tirelessly, again and again scooping up excess water with buckets and pouring it over the side of the boat, until daylight came. In the morning light the crew members could finally see each other’s pitiful, bone-weary appearances.

Figure 17,Charles Tong Sing. Naval Historical Heritage Command.

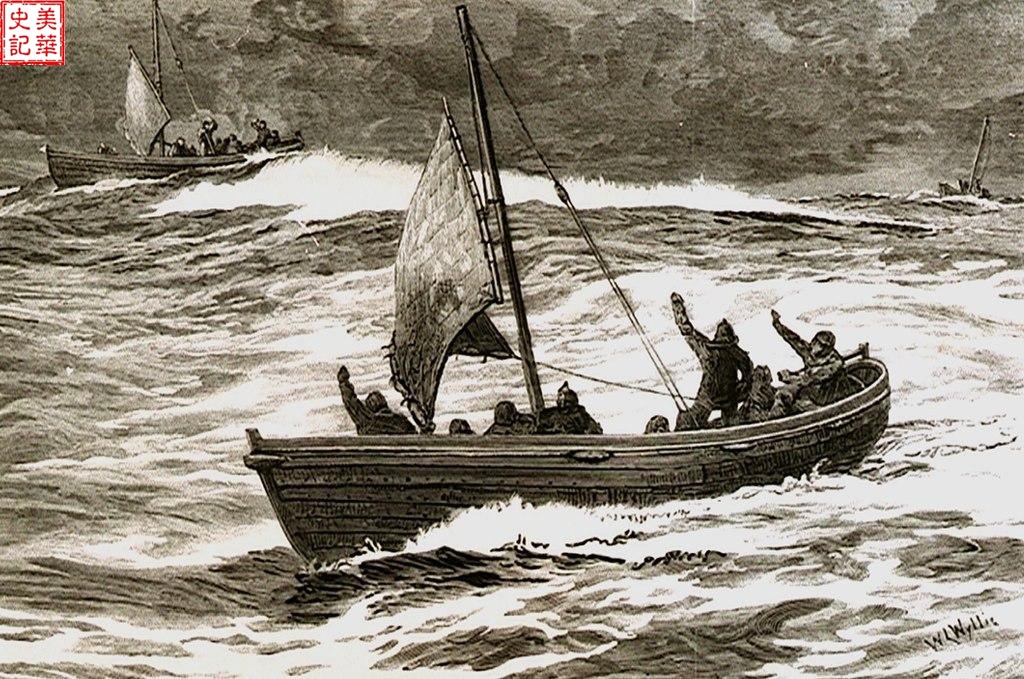

After being blown apart by the wind, Melville and Tong Sing’s lifeboat traveled alone at sea for two days, until they reached the Lena Delta, where they waded through ice and mud just to reach the shore. At that time, since the sinking of the Jeannette, they had been fighting for their lives on the icy seas for 88 days and had traveled 700 miles.

Siberia

Fortunately for them, they had landed in a place with people around. Two days later, on September 19, they encountered a hunter, who brought the 11 of them to some nearby residents’ houses.

Figure 18,high-altitude photo of the Lena Delta. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Malakatyn_B.Lyakhovsky_Island_2010-09-28_Boris.jpg/1024px-Malakatyn_B.Lyakhovsky_Island_2010-09-28_Boris.jpg?1602469222644

A few weeks later, a Russian passersby mentioned two Americans who were currently recovering at a nearby settlement called Bulun. Melville, upon hearing the news, headed to Bulun on November 3. At Bulun were Nindemann and Noros, who upon seeing Melville, promptly embraced him.

Figure 19,DeLong, Ah Sam, and the rest of the crew arriving at the Lena Delta. Naval Historical Heritage Command.

Once Melville had time to talk with the two, he found out that DeLong’s party had landed in the Lena Delta too, but in an area far from any people and therefore any help. DeLong ordered Nindemann and Noros to go seek help. The two of them ran into a windstorm and were rescued by a hunter, who brought them to Bulun. To their dismay, though, because they could not understand the residents, they could not communicate their plight.

After hearing this situation, Melville instructed the local residents to try to find any clues as to DeLong and his party’s whereabouts. After some searching, they finally found a clue: Someone found Jeannette’s daily log and other materials on a pile of rocks.

At that moment Melville understood. DeLong and his party were already dead, but it was his duty to find their bodies and the other important materials from the voyage.

Melville sent out an announcement to the residents: Whoever could find the expedition’s sleds and bring them to Yakutsk, the biggest village in the area, would get the expedition’s lifeboats, plus 500 rubles. Whoever could find the missing expedition members or any trace of them would be rewarded with 1000 rubles.

The Journey to Yakutsk

Figure 20. Map of the Lena watershed.

Melville, Tong Sing, and the other survivors traveled by sled over hundreds of miles to Yakutsk. By then, it was December 17, 1881, and they had not had any contact with outside groups of people for 29 months. Yakutsk was their first glimpse of civilization in more than two years.

When they heard the news, the villagers all flocked around to gawk at the group of Americans that had arrived. There were many people who would passed through Yakutsk, but most of them were from Moscow, Cremia, Poland, or were exiles or convicts. The Americans were a new, peculiar attraction.

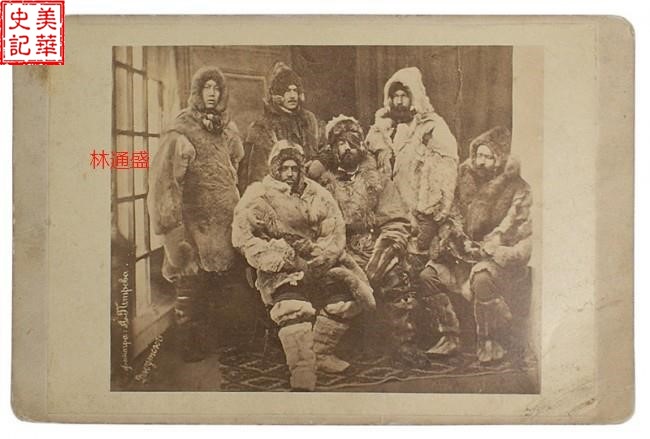

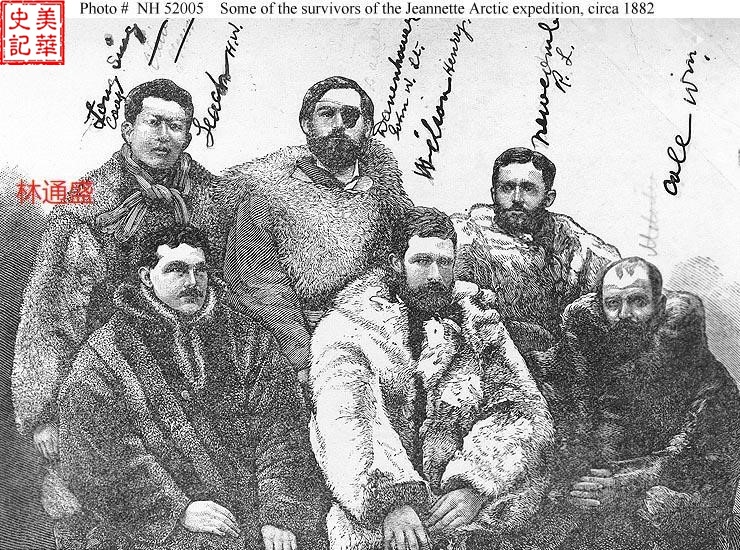

Figure 21,Charles Tong Sing (first from left) and five of the other expedition members at Yakutsk. Naval Historical Heritage Command.

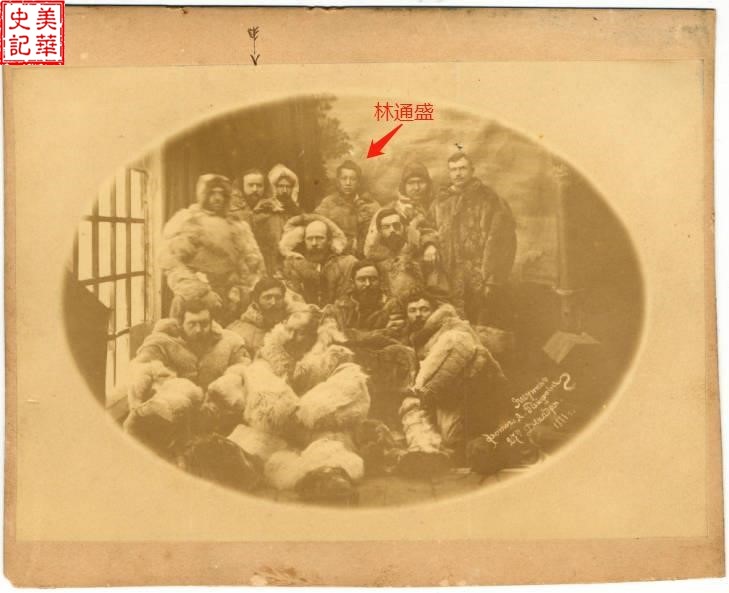

Figure 22, the 13 survivors of the expedition together at Yakutsk,the man in the middle of the back row is Tong Sing. http://p2.la-img.com/1022/26983/10158629_1_l.jpg

Yakutsk, though, had basically no means of communication to most of the world. The closest telegraph station was more than 2000 miles away in Irkutsk. Despite this, the expedition still got the news that the United States had elected a new President: James Garfield, who had been assassinated in the same year.

Figure 23,six of the survivors of the Jeannette, back row, first from the left is Tong Sing. Naval Historical Center.

In time, the New Year came. On New Year’s Eve all the important figures of Yakutsk and the expedition members celebrated together, drinking alcohol, dancing, and playing games.

In January of 1882 Tong Sing and 11 of the survivors of the Jeannette set off a brand new journey. This time, they would be traveling to St. Petersburg, all the way across Russia, and then to London, where they would be boarding a steamship back to New York.

Melville was the only one who decided not to return home immediately. Instead, he returned to the Lena River Delta to find his missing friends and comrades.

Leather Shoelaces, Ah Sam’s Last Source of Warmth

After resting in Yakutsk for a week, Melville led a search party comprised of local guides and some of the expedition members back to the Lena Delta to search for DeLong and Chipp’s parties. The Russian province governor became involved as well, providing men and supplies: sleds, reindeer, dogs, digging tools, and salted fish. [p. 386]

Because of the fearsome wind which had persisted for a month, Melville and the search party spent a month trying to get back to the Lena Delta. It wasn’t until about March 20 that the wind started to ease.

Melville first determined the most likely area for DeLong to have set up camp, and then thoroughly combed the area. A week passed with no clues.

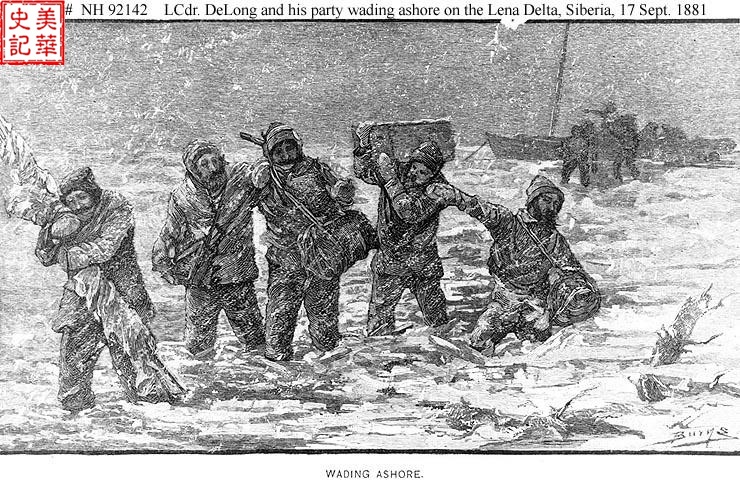

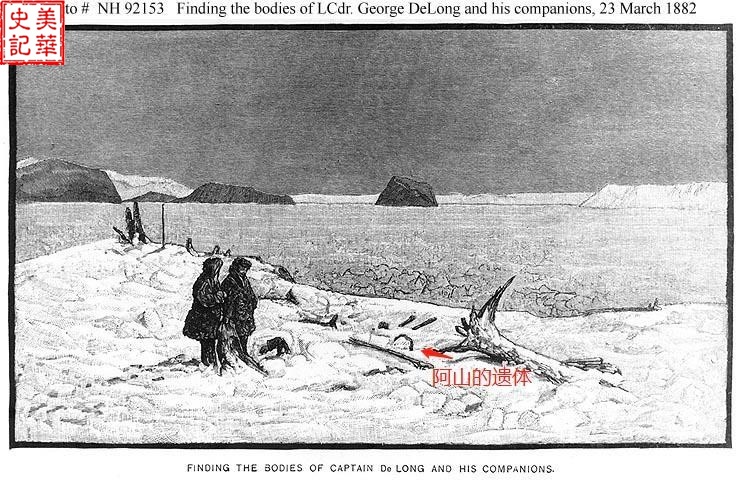

On March 23 Melville, in the white haze of the snow, saw a black object thousands of miles in the distance. Upon approaching the object, he found a bundle of sticks, bound together with a rope, and a gun, which he immediately realized was Alexey’s. He promptly ordered his men to conduct a meticulous search of the area.

Walking along the site where Alexey’s gun was found, Melville found a piece of cloth, then suddenly caught a glimpse of a pair of gloves half hidden in the snow. Next to a mound of charcoal was a tree trunk dragged in from the river and a copper kettle. He tried picking up the kettle, but then promptly fell over in surprise—an arm rose out of the snow, twisted at a strange angle. Melville immediately called for Nindemann, one of the other members of the expedition that had decided to stay behind.

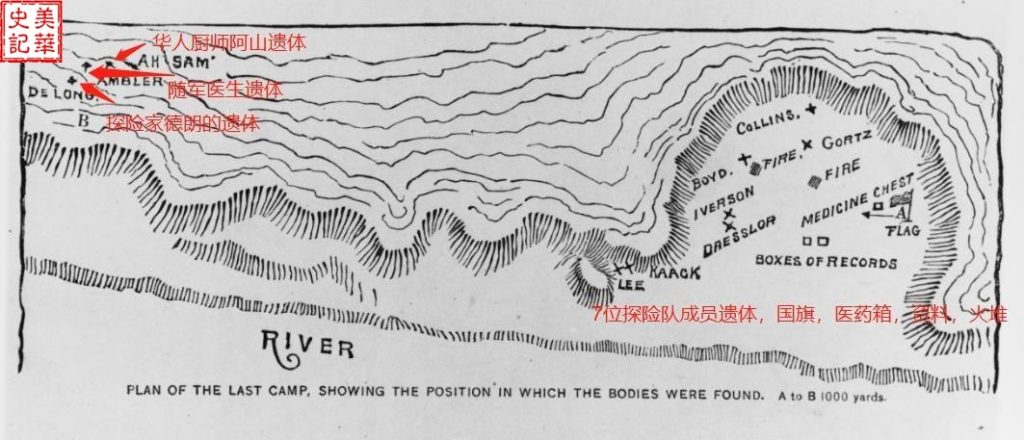

Figure 24, finding the bodies of DeLong, Ambler, Ah Sam, and the others. Naval Historical Center.

There were three bodies in total: DeLong, Ambler, and Ah Sam. They were determined to have died in a similar time frame.

Figure 25,map showing the location of DeLong’s camp and the bodies. Naval Historical Center.

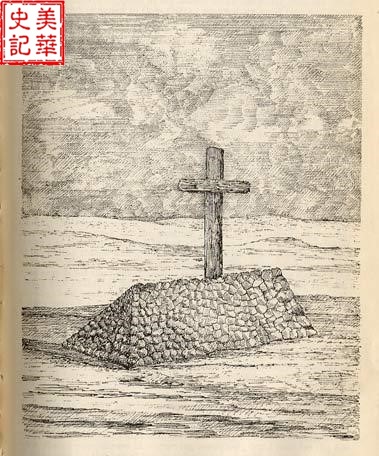

Melville and the search party buried DeLong and his companion’s remains, piling some rocks on top and then erecting a solemn, simple wooden cross.

Figure 26,DeLong and his party’s temporary grave in the Lena Delta. Naval Historical Center.

The Return Home,Reporting to the Navy

On May 8, 1882, Tong Sing and his fellow expedition members, 4 in total, returned to New York. Their team leader was Danenhower. [7]

As a result of long hours of staring at the blinding snow, Danenhower’s sight in his left eye had taken a hit. The doctors told him it would likely never recover, to which replied, jokingly, that his right eye sympathized with his left eye.

Another expedition member, Cole, because of the extreme mental stress of their “escape,” lost his memory. However, he could still recognize his son and brother, who were there to welcome him home. Shortly after that, he lost his memory completely and was sent to a nursing home.

Of the four, Tong Sing ended up the healthiest and the strongest. When asked if he would ever consider going to the Arctic again, he smiled mischievously and replied, “Yes, maybe.” [8]

On June 2, 1882, Danenhower and Tong Sing headed to Washington DC to report to the US Navy. They reported the expenses of the expedition and handed up all the things they brought back from the expedition: DeLong’s rifle, their geological survey specimens, etc. [9]

DeLong, Ah Sam, and the Others’ Funeral

Chipp’s party had been missing since September 12, 1881, when the gale blew the three lifeboats apart. In February 1882 the Secretary of the Navy ordered a search party to the Lena Delta to find Chipp, and also devised a plan to recover DeLong’s party’s remains.

On February 22, 1884, a funeral was held for the unfortunate members of the crew, at the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Midtown Manhattan. When DeLong, Ah Sam, and the others’ coffins were lowered off the ship, the pier and streets of Manhattan were full of soldiers and regular citizens, come to welcome them home.

At the church DeLong’s wife and daughter sat in the front row, with Melville to their side, and Tong Sing and the other survivors last.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the event as such: Ah Sam, the Chinese man who died in the Arctic, had a brother who came to the funeral. He carried an air of deep sorrow, motionlessly eyeing his brother’s coffin. Because the area was too dimly lit, the candles on the wall were lit up, which only served to increase the sadness of the scene. [10]

Figure 27, the expedition members’ funeral was held at the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Midtown Manhattan. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holy_Trinity_Episcopal_Church_(Manhattan)#/media/File:Dr._Tyng’s_Church,_Madison_Avenue,_New_York,_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_crop.png.

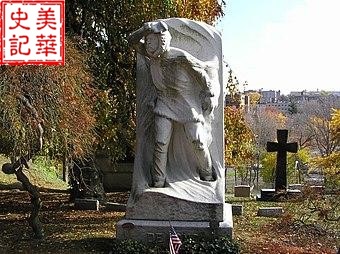

Once the funeral was over, DeLong and five other expedition members’ remains were interred together in the Bronx District’s Chapel Hill Plot, Woodlawn Cemetery. From Manhattan, it’s a quick ride on the subway to the cemetery, where you can easily spot Delong and Ah Sam’s gravestones. This is because in 1888 DeLong’s wife had a monument to DeLong built, which you can see in the picture below. Ah Sam’s gravestone is right in front of DeLong’s monument.

Figures 28-29: the gravestones of DeLong and Ah Sam in the Bronx. https://military.wikia.org/wiki/George_W._DeLong

On June 24, Tong Sing requested to leave the Navy to see his parents. [11]

Two Chinese Americans Receive Awards for Bravery for the First Time in History

In 1882 the US Navy awarded all the surviving members of the Jeannette.

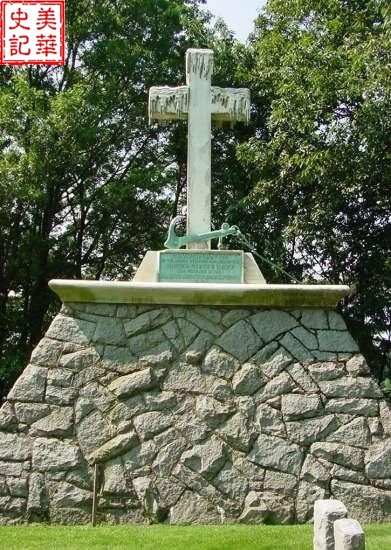

In 1890 the US Naval Academy erected a monument to the soldiers who lost their lives in the Jeannette expedition. The appearance of the monument was modeled after the temporary grave in the Lena Delta. The names of the dead expedition members are also inscribed on the monument.

Figure 30, the Jeannette Monument in the US Naval Academy Cemetery. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeannette_Monument#/media/File:Jeannette_Monument.jpg

In 1890 the US government passed an act issuing a gold or silver Congressional medal to every member of the Jeannette. Tong Sing and Ah Sam were awarded the same kind of medal, a silver one.

In December 1892 Tong Sing formally received his medal. It was also the first time a Chinese American had ever been awarded a medal for bravery. Engraved on the front of the medal is Charles Tong Sing, the other side has a depiction of the crew escaping from the Jeannette. [12]

Figures 31-32:Charles Tong Sing’s Congressional medals. https://www.flickr.com/photos/coinbooks/30394342048/in/dateposted-public/

Ah Sam is not only the first Chinese American to be in the US Navy, but also the first Chinese American to die in duty.

As a member of the Jeannette Expedition, Ah Sam’s name is on the US Navy’s website.

Figure 33, Ah Sam’s page on the US Naval History Arctic Expedition website. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Charles Tong Sing, on the other hand, safely returned to the United States. At the time, he was still only 23 and his story had just begun. In the next part we will continue his story.

Part 2:First Chinese American in the Arctic :Charles Tong Sing returns to the Arctic to Save Greely

Bibliography

1. Hampton Sides “In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette “, May 26, 2015 p.46

2. ibid p.149

3. ibid.p.180

4. ibid.p.208

5. ibid.p.230

6. ibid.p.301

7. Buffalo Weekly Express 01 Jun 1882, Thu p.4

8.Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 15, Number 83, 29 May 1882

9.Marysville Daily Appeal 3 June 1882/Marysville Daily Appeal, Volume XLV, Number 131, 3 June 1882

10. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1884/02/22

11. New York Times, 1882/06/25

12. San Francisco Call, Volume 73, Number 30, 30 December 1892

Abstract

Charles Tong Sing, Ah Sam were part of the 1879 US Navy Artic Expedition on Jeanette. While Ah Sam perished on Lena Delta in Sept. of 1881 at the side of De Long the Captain, Charles Tong Sing was one of the 13 survivors out of the initial 33 members of the crew.

Very impressive presentation, Cathy. You did a lot of research to bring this remarkable story to life.

Pingback: Promoting National Museum of AAPI – 美华史记