Author:Zhida Song-James

Translator: Ella N. Wu

ABSTRACT

The first Transcontinental Railroad in America was built from 1865 to 1869, which connected the east and west coasts of the American Continent for the first time in history. More than ten thousand Chinese immigrants worked on constructing the most dangerous segment of this railroad. In the treacherous terrain of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, while enduring all sorts of extreme weather, Chinese construction workers toiled from dawn until dusk to blast tunnels, chip away granite cliffs, and lay hundreds of miles of track. Many of these workers perished under such dangerous conditions. However they were erased in history as “silent spikes,” as no Chinese worker was confirmed to have attended the ceremony to celebrate the railroad completion in May, 1869.

This article tells the stories of these Chinese railroad workers–their courage to overcome challenges to build this great engineering project as well as their lives after its completion. 2019 will mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Transcontinental Railroad. Following the footprints of Chinese workers, while revisiting this significant part of the history, the article demonstrates Chinese railroad workers’ remarkable contributions to building this great nation.

The Transcontinental Railroad

In 1850, California became the 31st state in the United States of America. In the next few years, the gold mining industry developed rapidly and the population increased dramatically. The first silver mine was discovered in Nevada in 1858. After the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the federal government needed to control the rich mineral resources in the west to support war needs. Nevada quickly became a federal territory, and it became an urgent need to connect the political and industrial centers of the east with the important resources in the west. In 1862, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, encouraging people in the east to migrate west in order to develop the sparsely populated west. That’s when the idea of building a continental railway sparked. With the approval of Congress, Union Pacific Railroad was contracted to construct the eastern portion of the railroad starting in Omaha, and Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was contracted to construct the western portion.

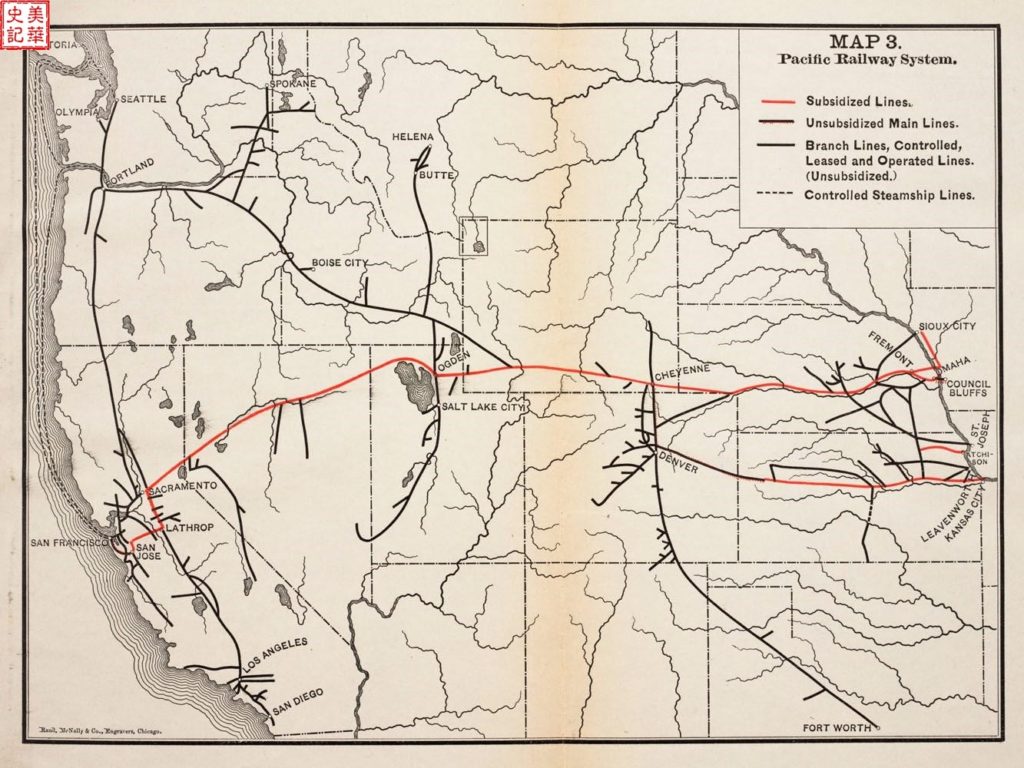

On January 8, 1863, the Central Pacific Railroad Company began construction in Sacramento, the capital of California. The planned route goes from Newcastle, California, through the Sierra Nevada mountain range–which is steep and snow-covered all the year round–through the east slope of Truckee, and enters the sparsely populated Nevada desert. Continuing east, the railroad route follows the Humboldt River in the Great Basin, through Wells and then northeast into Utah. The railroad’s eastern and western portions meet at Promontory Point, Utah. The railway brought people to the west, connected them to mining areas, and resulted in many towns forming. Now Reno, Winnemucca, Battle Mountain, Elko, Wells, etc. along the I-80 are all towns that prospered because of the construction of the railway.

Figure 1: Map of the Pacific Railway. Source: Linda Hall Library of Science Engineering Technology http://lhldigital.lindahall.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/rr_maps

Figure 2: The Sierra Nevada Mountains near Carson City. Source: US Geological Survey, for public use

Figure 3: Looking east to the Great Basin Source: https://www.googlefreephotos.com

This was a major, unprecedented project for the United States. When it first started, the Pacific Railroad estimated that it would require 5,000 workers to build, so it began to publish recruitment advertisements in newspapers across California. At this time, the civil war had not yet ended California’s mining and agriculture industries also required a lot of manpower, and there was a shortage in the labor market. Two years after the beginning of the railroad’s construction, only 800 people were recruited and less than 50 miles of railroad tracks had been laid. The company realized that the completion of the railway would have to rely on the Chinese workers who were called “Celestial workers” at the time [1].

As early as 1858, Chinese workers had begun to build railways in California. According to a report by the Sacramento Union, the California Central Railroad once hired fifty Chinese workers to build the Sacramento-Marysville railway. It didn’t take long for their reputation of hard work, perseverance, and reliability to spread in the engineering world [2]. In February 1865, the Central Pacific Railway Company hired the first batch of Chinese workers. Most of these people were “Golden Mountainer” during the gold rush. After the gold rush entered an industrial scale the Chinese were either completely kicked out or could only do the most menial jobs in the industry. The salary for working on the railroad was decent, so many Chinese thought it was a good opportunity. These Chinese workers had lived and worked in the United States for a period of time, knew some English, and had some understanding of the local society. At the beginning, the company only allowed them to level the roadbed by shovels and picks. Soon, however, the Chinese workers began to chop down trees, fill and excavate earth, lay railroad tracks along the route, gradually taking on all kinds of tasks in construction. They were silent, diligent, responsible, and hardworking. By the time the railway climbed along the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada to Colfax in the fall of 1865, the number of Chinese workers had increased to more than 3,000.

When no more Chinese workers could be hired in California, the Central Pacific Railway Company turned to Chinese labor intermediaries and directly advertised to recruit laborers out of China. At that time, the Taiping Rebellion was occurring (1851-1864). The chaos of the war displaced farmers and made it difficult to earn a living. Overseas recruitment brought them hope. They left their hometown, boarded the Pacific Mail Line and crossed the ocean to San Francisco, and then traveled by boat up the Sacramento River. The Central Pacific Railway Company sent them up the hillside to join the ranks of other Chinese construction workers. These people did not speak English, unlike the Chinese that had lived in the US for a while.

Usually 10 to 20 people from the same place would form a small team, live in the same shed, and jointly pay for Chinese food. Each team had an English speaking person as the leader, who is responsible for purchasing rice, peanut oil, dried fish, vegetables, dried fruits, sugar and other food as well as daily necessities from Chinese businessmen. The leader would also deal with the foreman on the construction site [3] [4].

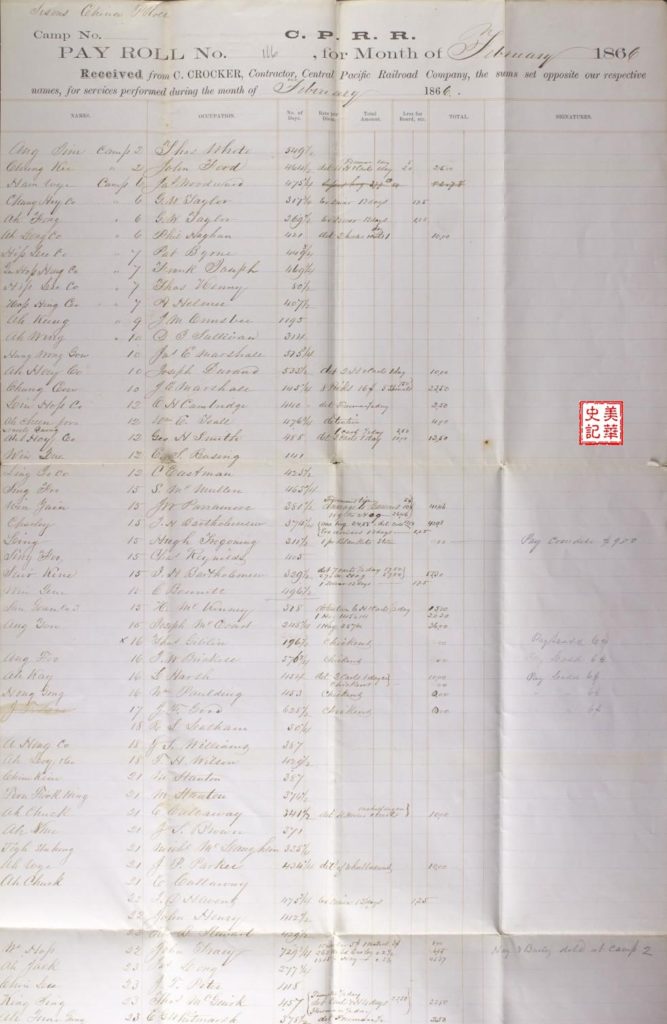

When the salary was paid at the end of the month, the leader would take it for the whole team and distribute it to everyone. Perhaps because of this reliance on intermediaries, people have not been able to find the names of all the Chinese workers on the Central Pacific Railway’s payroll.

Figure 4: Central Pacific Railway’s wage table of Chinese workers in February 1866. Source: Stanford University North American Railway Chinese Engineering Research Project http://web.stanford.edu/group/chineserailroad/cgi-bin/wordpress/sisons-china-proll-cprr-payroll-no-116-february-1866/

To this day, the traces of this organization can still be seen in China’s labor overseas . This team formation provided Chinese workers with a relatively familiar and convenient living environment, which was a comfort to the lonely soul far away from home. Forming groups also improved work efficiency. At the same time, it allowed the Chinese workers to rely on teammates, while being relatively isolated from the outside world.

The man who conquered the mountain

It’s quite accurate to describe the Chinese railway workers as “splitting mountains to pave the way.” There were three major difficulties in the construction of this railway. In the 1860s, the industrial center of the United States was in the east, and all kinds of railway materials like rails, wheels, carriages, spikes, locomotives, and road construction machinery could only be manufactured in the east. tThe Panama Canal had not yet been completed, and various materials could only be transported from the sea to the west coast via Cape Horn in the southern tip of South America. There were no good roads and heavy-duty bridges from the port to the construction site. Due to the astronomical transportation cost of such long distances and road restrictions, it was almost impossible to use machinery, and road construction mainly relied on human labor.

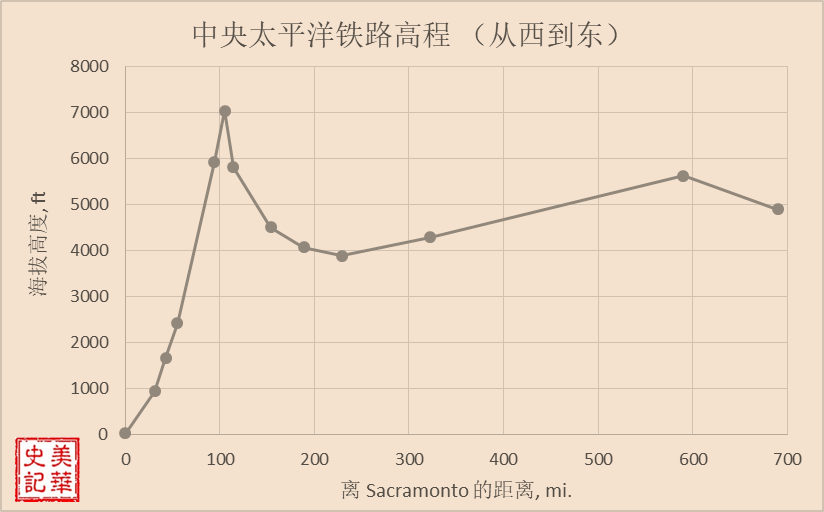

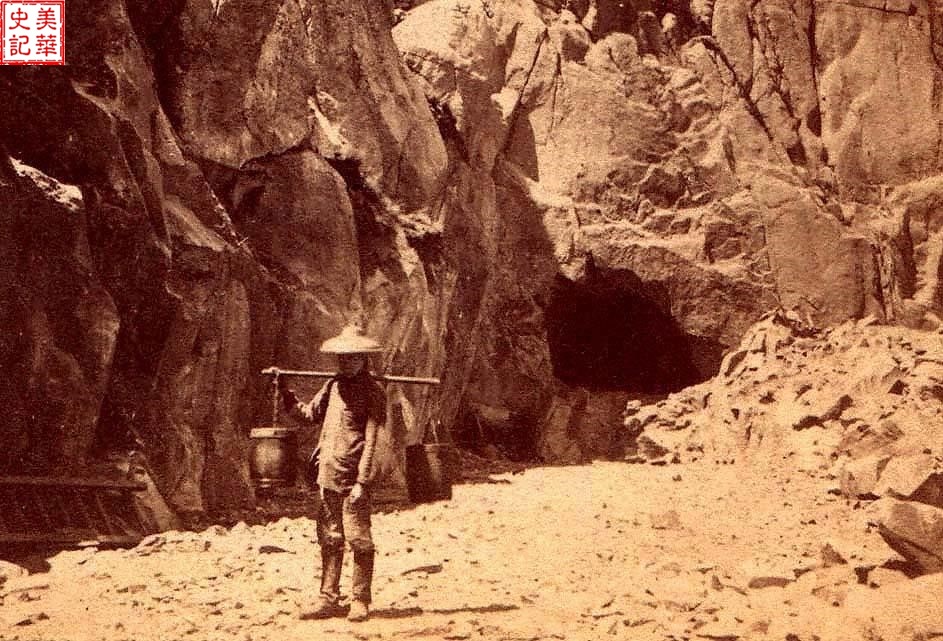

The Sierra Nevada runs north-south, and the railway crosses the mountains, starting from Sacramento at an elevation of 30 feet, climbing a west slope in a straight line of 105 miles to Donner Pass at an elevation of more than 7,000 feet. On the steep mountain, the Chinese workers blasted rock and laid roadbed at least 8 feet wide on the cliffs. At high elevation of six to seven thousand feet, 15 tunnels were dug on the hard granite mountain with a total length of 6213 feet [5].

Figure 5: The elevation of the Central Pacific Railroad, with Sacramento at the zero point, the highest tunnel at Donner Pass at the top, and Promontory Point at the junction at the east end.

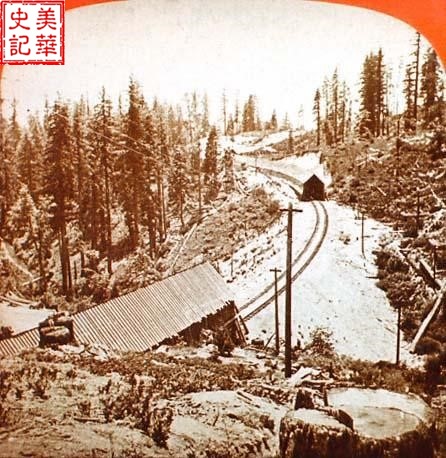

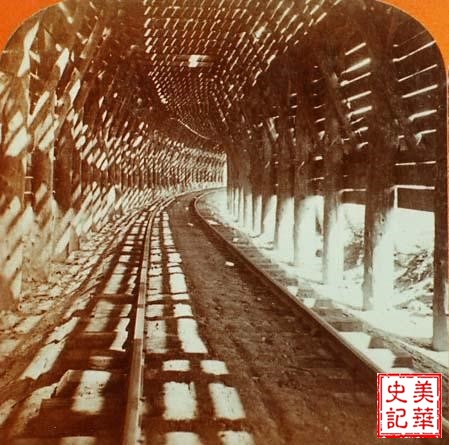

There was heavy precipitation in the Sierra Nevada from October to April of the following year. The winter of 1867-1868 was infamous for its blizzards. There was a heavy storm that lasted more than ten days, with the depth of snow accumulated up to 10 feet. The total amount of snowfall throughout the winter exceeded 44 feet [6]. Workers spent a lot of time clearing the snow. In the deepest part, the Central Pacific Railroad had to use 12 locomotives to open a passage in the ground [7], and set up a 37-mile snow-proof corridor above the roadbed to continue construction.

Figure 6: Alpine snow corridors. Road builders jokingly called them the highest and longest barns in the world. Source: New York Public Library Robert Dennis Stereograph Collection, reprinted from http://www.cprr.org/Museum/Eastward.html#Construction of the CPRR

The campsite of the railway workers moved with the laying of the railroad tracks. The Central Pacific Railway Company provided tents to workers, but many Chinese workers still lived in sheds and pits. During seasons when the mountains were covered by heavy snow, only the chimneys and vents of their huts could be seen from the ground. To go to work, you had to go through a passage with snow walls on both sides, down the snow steps to the working surface, and work under the dim light. There is no exact figure on how many Chinese workers were buried in the repeated avalanches. It is only known that the remains of some people were not discovered until the spring of the following year. Under such extremely difficult and dangerous conditions, the railroad tracks still continued construction inch by inch every day.

The main method of tunneling was blasting. Every 30-40 Chinese workers formed an engineering team, led by an Irish foreman. Workers worked in three shifts a day, each working eight hours, and the foreman changed shifts every 12 hours [8]. The Chinese workers toiled twelve hours a day, six days a week [9]. When digging the Donner Pass tunnel, the highest and most difficult tunnel, the company specially hired the prestigious Cornish miners from the United Kingdom [1]. The Chinese workers dug from one end of the tunnel, and the Cornish miners from the other. The chief engineering officer Clark (Charles Crocker, note 2) was very satisfied with the work of the Chinese workers. He described the results of this experiment, saying, “we measured the work every Sunday morning; and Chinaman without fail, always out measured Cornish miners.” [10].

Figure 7: Chinese workers outside the unfinished tunnel 8 Source: http://cprr.org/Museum/Steve_Heselton/_h204.tunnel8_sh.html

After nearly two years of hard work, the railway finally passed the Sierra Nevada and entered the relatively flat Great Basin The first forty miles were all desert, and there was no water or inhabitants. Across this area was the Humboldt Sink, Humboldt River from the eastran out of water here and was unable to reach the ocean. From here, the railway followed the Humboldt River valley to the east, crossing the Great Basin.

During its peak, the number of Chinese railroad workers exceeded 10,000, but almost no Chinese were among the engineering and technical personnel. In September 1868, when the Central Pacific Railway was repaired to Winnemucca, Chin Gee Hee was living here. A few years ago, he had come to the United States with a country man who had from California returned to Taishan, China to visit relatives. Witnessing the continuous extension of railroad tracks in the desert and the roaring of iron horses, he became very interested in railway engineering and joined the road construction crew of the Central Pacific Railway, starting as a handyman. Under the encouragement and guidance of the engineers, he began to study railway engineering. Smart and hardworking, he quickly mastered certain skills and became an engineer’s assistant. His deeds are recorded in the Nevada State Museum [11].

Strike on the mountain

The Central Pacific Railway Company had a majority of Chinese laborers, and the company has always employed a certain number of white workers. Wages were paid in gold coins with the best credit at the time, and paid to the workers at the end of each month (Table 1). However, the wages and benefits seemed to be different: the company provided food and lodging for white workers, while the Chinese workers were responsible for themselves. Chinese workers often worked more than ten hours a day from morning to night. The white laborers often treated the Chinese workers rudely and harshly, which caused widespread indignance from the Chinese workers.

Table 1: Number and wages of Central Pacific Railway workers, 1864-1869

| 年份 | 华工人数 | 每月薪水 | 白人人数 | 每月薪水 |

| 1864 | 极少 | 不详 | 1200 | $30 |

| 1865 | 7,000 | $30 | 2,500 | $35 |

| 1866 | 11,000 | $35 | 2,500 – 3,000 | $35 |

| 1867 | 11,000 | $35 | 2,500 – 3,000 | – |

| 1868 | 5,000 – 6,000 | – | 2,500 – 3,000 | – |

| 1869 | 5,000 | – | 1,500 – 1,600 | – |

Source: Testimony of J. H. Strobridge, US Pacific Railway Commission, pp 3139-41, as printed in Stuart Daggett: Chapters in the History of the Southern Pacific, p 70.

On June 25, 1867, about 90 miles east of Sacramento, the 3,500 Chinese workers who dug the tunnel on the Sierra Nevada, where the snow still remained between Cisco and the summit, laid down their tools and walked out of the construction site in an orderly manner. This was the first recorded strike by Chinese workers in the United States. The organizer of the strike is still unknown. The representatives of the Chinese workers put forward three requirements to the company: 1. The working hours per day should not exceed ten hours; 2. The salary should be increased from US$35 to US$40 per month. 3. The foreman was not allowed to hit the worker, so as to protect the worker’s right to find other jobs [12] [13].

The calm and organized strike surprised the company. The company first planned to hire Black people who had been freed not long ago to replace the Chinese workers. After the recruitment failed, the company stopped supplying Chinese workers with food and various daily necessities, claiming that they would fire all the Chinese workers who went on strike, and refused to provide them with transportation to return to the foot of the mountain. The Chinese workers were trapped on the high mountains without food or drink. Eight days later, the hungry Chinese workers agreed to resume work, and the Central Pacific Railway finally raised their monthly wages by two dollars [14].

Where to go after railroad completion

On May 10, 1869, railroads from the east and west were connected in Promontory, Utah, declaring the completion of the railroad across the North American continent.

Figure 8a: Promontory, Utah, taken by the author in 2018, copyright.

Figure 8b: There are still relics of the mountain that opened on the rock, taken by the author in 2018, copyright.

Figure 8c: The junction of the Central Pacific Railway and the Union Pacific Railway, taken by the author in 2018, copyright

Picture 8d: This place is called China Gate, which commemorates the Chinese workers who built the railway here. The author was taken in 2018, with the copyright

This railway not only connected the east and west, but also brought great changes to the lives of residents along the railroad. The Winnemucca Regional History states that “The railway brings the outside world to Winnemucca, and also brings Winnemucca to the world. With this railway, the Humboldt County center moved to Winnemucca. This place will definitely prosper in the future.” The cowboys of the Humboldt Valley Ranch proudly looked forward: “In the future, all the beef in the restaurants in San Francisco will be produced here.” On the day the first train passed through the town, people were gathered and celebrated. They drank, shot a pistol in the sky, and celebrated in a way unique to the west [15].

As soon as the golden spike drove into the ground, residents along the railroad bursted out in joy, looking forward to the future. However, immediately after construction, the Central Pacific Railway Company fired almost all of the Chinese workers, except for the hundreds of maintenance personnel who remained at the stations along the ruote. What were the whereabouts of these Chinese workers?

Build roads and walk the world

Some Chinese workers continued to build railways in the western states. The Southern Pacific Railway Company hired a group of Chinese workers to extend the northern California railroad to southern California, which brought rapid development and prosperity in the 1880s for southern California [16]. In 1870, the Northern Pacific Railroad established a base in where is now Kalama, Washington. It planned to build a railroad from there northward connect to the Northern Pacific Railroad, which was advancing westward from Minnesota. The project managers recruited a large number of Chinese workers. Kalama even had a Chinatown called China Garden. The Chinese workers had left their footprint in the Montana portion of the Northern Pacific Railway, the Alabama and Chattanooga Railway from Alabama to Tennessee, and the Houston and Texas Railway from the Lone Star state.

The mines in California and Nevada needed to build branch railroads to connect with the main continental railway. Construction of the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railway started in 1875, and the contractor hired 300 Chinese laborers. When there were no more Chinese workers to hire, 150 white men had to be employed. People said that the Chinese workers who earned 26 dollars a month were hardworking and self-disciplined, and did not complain about working long hours, while the white workers who earned 30 dollars a month drank on the payday and stayed drunk for several days after. You don’t need to think too much to understand that this railway was mainly completed by Chinese workers [17].

The pioneers of the delta

Those who did not stay in the railway industry had to switch jobs to earn a living. The delta in the confluence of the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers in central California was low-lying, with seawater to the west and frequent flooding during the spring snowmelt season. It formed a swamp with hundreds of uninhabited square miles. Only aquatic plants such as rushes and cattails and mixed shrubs could fend for themselves there. Farmers took an interest in this humus-rich land and bought it from the government at a low price. After the mainland railroad was repaired, California’s agricultural products became very popular in the markets of major eastern cities. Reclaiming the land was profitable, and all that was needed was cheap labor. Many Chinese workers who had built mainland railways turned into agricultural workers who reclaimed the Delta. They came from the rural areas of Guangdong and had experience in drainage and farming. The Chinese workers waded through muddy water, cutting tangled vegetation, dredging waterways, building river embankments, installing gates, enclosing islands with cofferdams on the delta, and opening up fields. In addition to growing vegetables and fruits, the land with abundant water was also suitable for growing rice. California rice agriculture developed in this way. To this day, large paddy fields can still be seen south of Sacramento. Although this project was not as famous as the Continental Railway, it also brought important wealth to California.

Figure 9: Today’s delta has regular channels and rich farmland. More than 90% of California’s agricultural products come from this area. Image source: California Department of Water Resource, https://www.kcet.org/redefine/understanding-californias-bay-delta-in-63-photos

Lumberjack work in the high mountain mining area

Another industry with a large number of Chinese workers was the logging industry, which was closely related to mines and railways. Nevada was very rich in mineral resources, but white-dominated labor unions did not allow Chinese to directly participate in mining. Opening a silver mine required wood as a roadway support, so it was necessary to cut down trees, transport them down the mountain, send them to the sawmill, and sell the remaining branches to miners for heating, etc. Each step in the process required a lot of manpower. Documents record that the Chinese once held a monopoly position in the logging industry; 70-80% of the loggers in the snow-capped mountains of Nevada in the 1880s were Chinese, and many of them were Chinese railway workers who changed their jobs [18]. Other Chinese workers transferred to the service industry. In addition to the well-known laundry industry, Chinese laborers also worked as cooks and servants in white houses.

From workers to labor contractors

During this period, the social class among Chinese workers became more obvious. During the construction of the railway, there were already leaders among the Chinese workers, managing the daily affairs of the Chinese and dealing with the company. This experience cultivated their leadership and communication skills, and many of them became labor contractors after the completion of the railway. The Chinese who could speak English often helped others find jobs. Railway companies, farmers, and logging industries often contacted these leaders when they needed Chinese workers. In addition to commissions, they also opened shops to provide Chinese workers with daily necessities such as food, lodging and transportation. This double-edged take-all status allowed them to accumulate wealth at a much faster rate than ordinary laborers in a short period of time. They changed from Chinese workers to Chinese businessmen, and distanced themselves from the lower-level workers. Their economic and social status enabled them to obtain a certain amount of legal asylum in the future anti-Chinese waves. Some people were able to retreat and return to China with the wealth accumulated over the years. Chin Gee Hee (Chen Yixi as current spelling) is one of them.

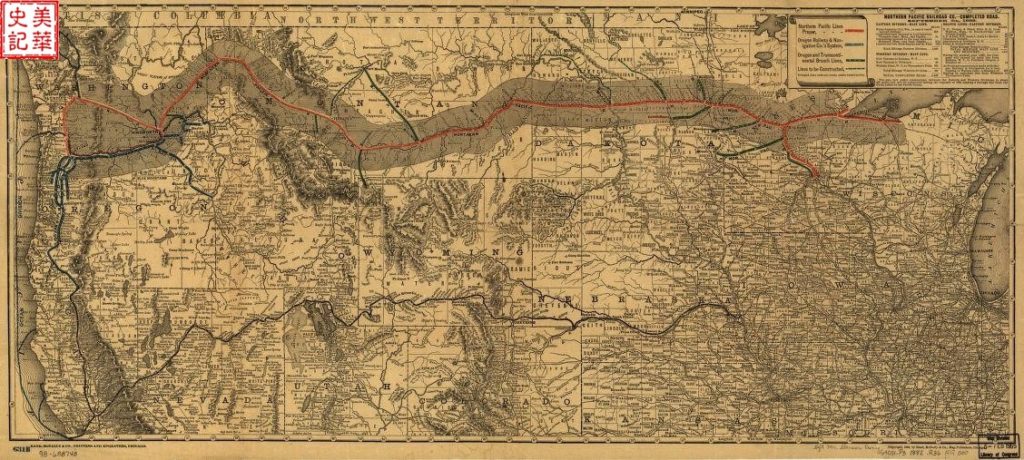

After the completion of the Transcontinental Railway, Chin Gee Hee worked in logging, port and other industries; in 1873, he moved to the emerging city of Seattle. Chin Chun Hock, a man also from Taishan, introduced him to join the prosperous Wo Chong Company as a manager. The company was originally engaged in the importing business, but after Chin Gee Hee joined, he mainly did labor contracting. His biggest customer was the Northern Pacific Railway Company, which constantly needed Chinese workers. The Northern Pacific Railway ran from Saint Paul in Minnesota in the east, Seattle and Tacoma, Washington in the west, and to Portland, Oregon. It was an important passage connecting the Great Lakes region with the Pacific harbors.

Figure 10: Northern Pacific Railroad Route, September 1882 Source: Library of Congress

With the progress of this project, the demand for Chinese workers greatly increased, and Chin Gee Hee’s career also flourished. In addition to recruiting, the labor contractors at that time also had to manage workers, and were responsible for arranging food and lodging, managing payroll, and filing taxes. Because of his familiarity with railway engineering, he participated in labor contracting during the construction of Grant Northern Railroad and Seattle-Walla Walla Railway in this area. Participating in these major projects made his company well-known in the business community, and he gradually rose to the status of a leader in the Chinese society.

An anti-Chinese riot broke out in the nearby Tacoma in November 1885. With the support of the city government, the rioters drove the Chinese to the railway station, forced them to leave along the railway (which was built by Chinese workers 12 years ago), and burned down their shops and houses. The Chinese in Seattle were also affected. Chin Gee Hee quickly telegraphed the situation to the Qing Consulate in San Francisco, demanding protection, and recorded in detail the losses suffered by the Chinese. Later, the Qing government was able to claim compensation based on his records. Chin Gee Hee continued to do business in Seattle until around 1904, when he left his American business to his son and son-in-law, and returned to China by himself [19].

China’s early railway construction and returning Chinese workers

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Westernization Movement (1861-1995) emerged in China, and the railway was one of the most important projects in science and technology imported from the West. The first state-owned and long-running railway in the Qing Dynasty was the Tang Xu Railway, which was completed in 1881. In 1893, this railway extended from Tianjin to Shanhaiguan and was renamed Jinyu Railway. Returned Chinese laborers played an important role in the construction of this railway. In 1896, the American consul in Tianjin, Sheridan P. Read, described in detail the history of the railway and its operating conditions at the time in a report, specifically mentioning that there were Chinese personnel who were bilingual in Chinese and English. In February 1896, the Engineering News and American Railway Journal published a summary of the report, stating, “The workers who built this railway have built the entire continent in California, Nevada, and Utah. They have also built a railway from the Central Pacific Railway Company to Oregon in the north and Los Angeles in the south.” [20] Unfortunately, we haven’t found their names yet.

The aforementioned Chin Gee Hee returned to China and made outstanding contributions to China’s railway industry. After his return, he presided over the construction of the Ningyang Railway. This railway, located in Xinning (Taishan) and Xinhui, Guangdong Province, China, was a total length of 59.3 kilometers. Construction started in 1906 and opened to the public in 1909. All funds for the construction of the railway were raised by Chinese at home and abroad. Among them, Chin Gee Hee and others raised more than 2.7 million silver dollars from overseas [21]. Engineering and technical personnel and road construction workers are also Chinese. Taishan City specially erected a monument to commemorate his outstanding contribution to China’s railway industry and his hometown.

Figure 11: The bronze statue of Chin Gee Hee next to Ningcheng Station. Source: https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-hans/Xinning Railway

More than 20 years ago, in a Chinese restaurant in Berkeley, the owner told me that the place was once a station for the Transcontinental Railroad. His ancestors were the Chinese workers who built that railway. Time flies. One hundred and fifty years have passed. With highways, airplanes, and other transportation networks, the mission of railways is still far from over. Today, on the vast plains and mountains of the west, you can still see two or three locomotives pushing and pulling trains several miles in length and hundreds of carriages, sending containers, petroleum products, heavy machinery, etc. everywhere. Amtrak also provides travel routes from Chicago to San Francisco to Los Angeles and along the Pacific coastline, so travelers can enjoy the magnificent scenery along the way. For all of this, I can’t help but thank the older Chinese workers who shed their blood, sweat, and tears to build the railroads.

“They tell us with their lives,

You must dare to bear any fate.

When you leave,

Your footprints will remain on the shores of the sea of time.”(Note 3)

Some of the senior Chinese workers passed away silently, and some were killed and driven away during the anti-Chinese wave. This railway is the indelible evidence left by them. Without Chinese workers, there would be no such railroad, and there would be no unified and powerful America. On April 29, 1999, Congressman John T. Doolittle from California pointed out in his speech in the House of Representatives, “Without the efforts of the Chinese workers in the building of America’s railroads, our development and progress as a nation would have been delayed by years. Their toil in severe weather, cruel working conditions and for meager wages cannot be under appreciated. My sentiments and thanks go out to the entire Chinese-American community for its ancestors’ contribution to the building of this great Nation.”

[22].

The achievements of these Chinese workers will live on forever.

Figure 11:The train parallel to I-80 in the Great Basin. The author was taken in 2018, with the copyright

Sources:

- Cornish Miners康沃尔矿工:英格兰西南角的康沃尔郡(Cornwall)有上千年开发锡矿和铜矿的历史,那里的矿工被誉为世界上最早也最能干的开凿隧道者。十九世纪中叶开始有康沃尔矿工 移民到美国西部。

- Charles Crocker 查尔斯 克拉克: 中央太平洋铁路四巨头之一,铁路施工总监,他的公司 Charles Croker &Co. 是中央太平洋铁路分包商,并在此基础上建立了南太平洋铁路公司。

- 集Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (朗费罗)人生礼赞 (A Psalm of life) 诗句,作者译。

Annotations:

- Samuel Montague, Report of the Chief Engineer upon Recent Surveys and Progress of Construction of the Central Pacific Railroad of California.” December, 1865. Courtesy of Lynn D. Farrar. http://www.cprr.org/Museum/Chinese.html

- Mae H. B. Boggs, My Playhouse Was a Concord Coach (Oakland, 1942): 310. Quoted from the June 15, 1858, issue of the Sacramento Union.

- Southern Pacific Relations Memorandum: The Chinese Role in Building the Central Pacific, Jan. 3, 1966.

- Charles Nordhoff, California, a Book for Travelers and Settlers (N. Y., 1873): 189-190.

- John R. Gillis, “Tunnels of the Pacific Railroad.” In Van Nostrand’s Eclectic Engineering Magazine, January 5, 1870, 418-423.

- Mark McLaughlin, Reign of The Sierra Storm King: A Weather History of Donner Pass, P7

- Iris Chang, The Chinese In America A Narrative History (New York: Penguin Group USA, 2003): 60.

- George Kraus, Chinese Laborers and the Construction of the Central Pacific, in Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol 37, No. 1(Winter 1969): 41-49.

- Zhang,2003: 61.

- Ronald Takaki: Stranger from a Deferent Shore: A History of Chinese America (Boston: Little Brown, 1990): 84.

- Nevada State Museum Exhibit,Las Vegas, 2018.

- Steven M. Graves: The Impact of the Railroad: The Iron Horse and the Octopus: 11, http://www.csun.edu/~sg4002/courses/417/readings/rail.pdf

- Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University, http://web.stanford.edu/group/chineserailroad/cgi-bin/wordpress/faqs

- Peter Kwong and Dusanka Miscevic: Chinese America the Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Community (New York: New Press, 2005): 55.

- J. P. Marden:The History of Winnemucca, The Central Pacific Railroad http://cprr.org/Museum/Winnemucca_Marden.pdf

- Graves: 9.

- Bob Wyckoff: ”Grass Valley’s Chinatown; not forgotten” in The Union. August 21, 2006.

- Sue Fawn Chung: The Chinese and Green Gold: Limbering in the Sierras, June 2003.

- Willard G. Jue, “Chin Gee-Hee, Chinese Pioneer Entrepreneur in Seattle and Toishan”, The Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1983, 31:38.

- The First Railway in China, Engineering News and American Railway Journal, Feb. 17, 1896.

- Lucie Cheng and Liu Yuzun with Zheng Dehua, “Chinese Emigration, the Sunning Railway and the Development of Toishan” in Amerasia Vol 9, No1 (1982): 59-74.

- Archive:gov/us/fed/congress/record/1999/apr/29/1999CRE822A [Congressional Record: April 29, 1999 (Extensions); Page E822.

Great article on the Chinese railroad workers.

Pingback: Promoting National Museum of AAPI – 美华史记