Author: Fin Qi

Editor: Audrey M. Jiang

United States citizenship law is founded on two traditional principles – “jus soli” (“right of the soil”) and “jus sanguinis” (“right of the blood”). A person born in the United States who is subject to the jurisdiction of the United States is a U.S. citizen at birth. However, this was not true more than 100 years ago. As a pioneer of Chinese immigrants in this country, Wong Kim Ark obtained his citizenship by challenging the U.S. law through “right of the soil” and later helped his sons (including one “Paper Son”) become U.S. citizens through “right of the blood”.

Wong Kim Ark, Born in the United States, Was Being Deported

On October 1, 1870 (1867, 1871 or 1873 from different sources) Wee Lee gave birth to a baby boy in the upstairs bedroom of a grocery store at 751 Sacramento Street, in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The boy was Wong Kim Ark, who would go down in the history of Birthright Citizenship in the United States (1, 2). Lee came to the U.S. with her husband, Wong Si Ping from Guangdong Province, China.

In the late 19th century, many Chinese immigrants came for the gold rush in California. They helped build the First Transcontinental Railroad, and worked as miners and merchants. A large number of Chinese laborers, almost all of them, were unmarried men. Consequently, it was quite difficult for a Chinese immigrant man of that time to find a wife. Data shows that only 2% of Chinese Americans were women in 1855, and that proportion increased to 4% in 1875 (3). As a result, very few children of Chinese descent were born in the United States. According to the U.S. Census, the Chinese population numbered 63,254 in the year 1870, and of those ~63,000, only 518 were children born in the United States (4). Wong was one of the few.

When he was 7 or 8 years old, Wong Kim Ark went to China along with his parents and 5-year-old brother. At the age of 10, he returned to the United States with his uncle, working as a dishwasher and cook in the Sierras (4). Soon after, Wong reached a marriageable age.

In the late 19th century, the United States introduced a series of discriminatory immigration laws restricting Chinese immigration. These laws included the Page Act of 1875 (5) and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In the name of restricting Chinese prostitutes, the Page Act effectively purged the population of Chinese women in the United States (6). In the months prior to the enactment of Chinese Exclusion Act, 39,579 Chinese entered the United States, of whom only 136 were women (7). In addition to this, the Act also prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States.

Figure 1. On February 18, 1875, Horace F. Page, a Republican from California, submitted an immigration proposal (the Page Act) to restrict immigration from specific groups of people. These specific groups included cheap Chinese laborers, “immoral” Chinese women, and all people considered convicts in their own countries. The Page Act was implemented on March 3, 1875.

Because the number of Chinese women in the United States was very low, it was difficult for a Chinese man at a marriageable age to find a wife and form a family in the United States. In accordance with the common practice of the Chinese people at that time, in 1890 Wong embarked on the road back home to find a wife. He married a 17-year-old girl (Yee Shee) in his hometown, and soon after his newly-married wife was pregnant with their first child. On July 26, 1890, before the birth of his son, Wong Kim Ark returned to San Francisco, thousands of miles away from his new family (4).

At that time, this new style of immigrant family life was an unfortunate reality due to immigration restriction. However, in many cases, the distance was not able to sever these relationships. Influenced by the ancient tradition, many men still earned enough money to support their families (8).

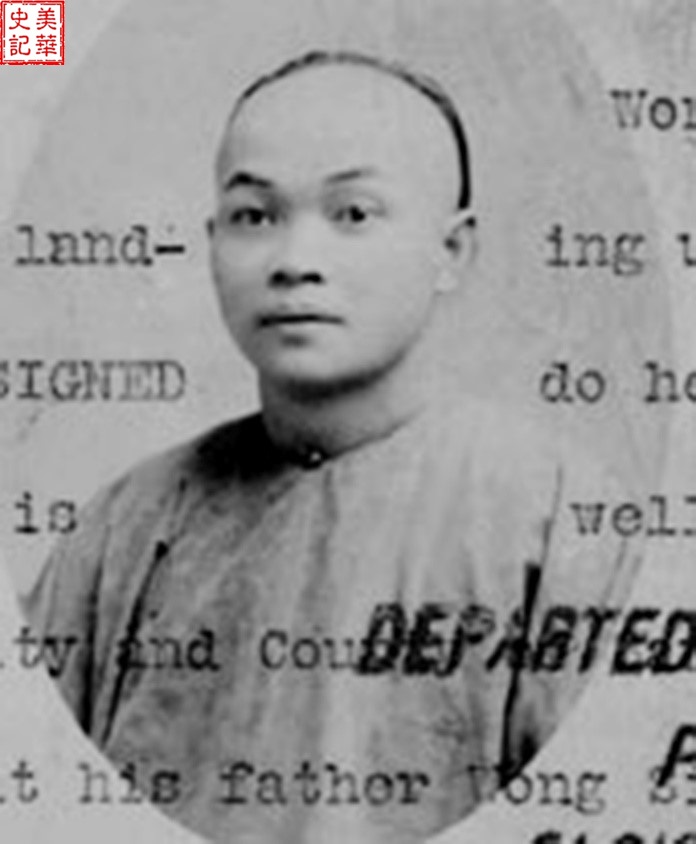

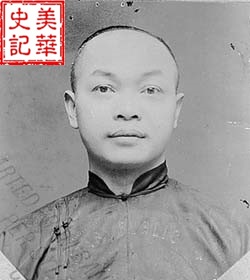

Picture 2. Wong Kim Ark, taken when he left San Francisco in 1894. He was described as quiet, peaceful and full of confidence. National Archives.

In December 1894, Wong returned to Guangdong where he met his eldest son for the first time after four years of being separated from his family. During the nine-month visit, Wong’s wife became pregnant with their second child. In August 1895, when Wong Kim Ark returned to the United States, he was denied entry to the country by the Collector of Customs and confined for almost five months on steamships off the coast of San Francisco before being released on a bail of $250 (4).

With support from the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, also known as the Six Companies, Wong Kim Ark decided to take legal action for Birthright Citizenship, also known as jus soli. A district judge, William M. Morrow, reviewed his case. On January 3, 1896, Morrow declared that Wong Kim Ark was a U.S. citizen based on “right of the soil”. However, the story was far from over. The U.S. government appealed the district court ruling directly to the United States Supreme Court, which resulted in the famous case United States v. Wong Kim Ark (11).

Wong and the Battle for Birthright Citizenship

The parents of Wong Kim Ark were people of the Qing Empire. Despite the fact that they did not live in, carry out business in, or were employed in any diplomatic or official capacity in China, , and were residents of the United States, their children being born in the United States was not enough for their children to be recognized as U.S. citizens.

U.S. citizenship law is founded on two traditional principles – “jus soli” (born in American territory – “right of the soil”) and “jus sanguinis” (parental citizenship – “right of the blood”) (12). The “Jus soli” is inherited from the English common law, in contrast to “jus sanguinis”, which derives from the Roman law that influenced the civil-law systems of mainland Europe. This applicability of “jus soli” was upheld in an 1844 New York state case, Lynch v. Clarke, in which a girl born in New York City, of alien parents temporarily sojourning there, was granted a U.S. citizenship (13).

However, prior to the Civil War, jus soli was not applicable to African-Americans (12). In 1857, the United States Supreme Court announced in Dred Scott v. Sandford that slaves, former slaves, and their descendants were not eligible under the Constitution to be citizens (14). After the Civil War, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and enacted the 14th Amendment to the Constitution in 1868.

According to the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the State wherein they reside.” The “subject to the jurisdiction thereof “ were intended to exclude the children of foreign diplomats, the children of enemy aggressors, and the children of Native Americans, all of whom were loyal to an independent sovereign power and were not necessarily bound by many federal and state laws (15).

As a result of the new 14th Amendment, newly liberated slaves and all persons not subject to any foreign power were granted Birthright Citizenship as long as they were born in the United States. However, Birthright Citizenship did not apply to American Indians, since Indian tribes were considered to be outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. government (Note: Congress eventually granted full citizenship to American Indians via the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924). At that time, the proportion of Chinese population was small and almost all of them were sojourners, so the Chinese were not under consideration for Birthright Citizenship. Wong Kim Ark was not the first Chinese person to challenge how Birthright Citizenship was applied; a few others had acquired citizenship through legal actions, such as Look Tin Sing, a Chinese businessman who was barred from reentering the United States by immigration officers in 1884 (16). Look’s case was heard in a federal circuit court in California by Judge Field. He won the case and was recognized as a U.S. citizen. But this case, like others pertaining to the question of Chinese citizenship, was not brought to the Supreme Court, resulting in a low level of awareness about the situation.

Figure 3. Look Tin Sing (left) was born in San Francisco on May 5, 1870. At the age of 5, he was sent to China to learn Chinese culture. Upon returning from China at age 14, he was barred from reentering the United States. He won his case in the federal circuit court of San Francisco and obtained his Birthright Citizenship.

San Francisco attorney George Collins criticized Judge Field’s decision in the Look case and accused the federal government for not challenging the Circuit Court’s decision in an article published in the journal of American Law Review in 1895. Collins tried to persuade the federal Justice Department to review a citizenship case of Chinese born in the United States in the Supreme Court. Eventually he was able to convince attorney Henry Foote to take the Wong case to the Supreme Court (10).

One stone stirred up a thousand waves. Debates were heated regarding interpretation of the 14th Amendment, especially what “subject to the jurisdiction” actually meant.

The objections of the U.S. government (lawyer Holmes Conrad) were straightforward, and they were as follows (17):

“Large numbers of Chinese laborers of a distinct race and religion, remaining strangers in the land, residing apart by themselves…and apparently incapable of assimilating with our people, might endanger good order and be injurious to the public interests.” Holmes Conrad, Reply Brief for the United States. Quoting Justice Gray, 149 US 747, p 717.

“As the respondent was born of alien parents, to wit, subjects of the Emperor of China, he was at his birth a subject of China, claimed by that nation as such, and therefore was not born “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States.” George Collins and Holmes Conrad, Brief on Behalf of the Appellant.

However, the lawyers of Wong Kim Ark (William Evarts, Joseph Hubley Ashton) argued that Wong, who was born in the United States, was a U.S. citizen and was free to travel between China and the U.S. Their main points were (17):

“He has always subjected himself to the jurisdiction and dominion of the United States, …and has been taxed, recognized, and treated as a citizen of the United States.” Thomas Riordan, Respondent’s Brief.

“Prejudice of race and pretension of caste were set aside by the Fourteenth Amendment, which ordained in unequivocal and far-reaching terms that ‘all persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States.’ The language cannot by construction or interpretation be confined…to persons of the Caucasian race and persons of African descent, to the exclusion of persons of Mongolian descent.” J. Hubley Ashton, Brief for the Appelle.

The San Francisco Call reported on February 8, 1896, “The question at issue is not one that affects American-born Chinese only, but every American-born son of a foreign-born father who did not become a naturalized citizen of this country prior to the time arrived at maturity. In this view of the case, one sees at a glance that many thousands of voters all over the United States are deeply interested in the knotty legal problem, though of course should the United States Supreme Court reverse the ruling of Judge Morrow, as it is confidently expected that it will, the American-born Chinese will be the only ones ultimately deprived of citizenship. Sons of non-naturalized Caucasians will merely have to secure naturalization in the ordinary way. But the Mongolians, while the existing Chinese restriction laws are in force, will be forever barred from citizenship. “ 【17】——San Francisco Call, Feb. 8, 1896.

Figure 4. Wong’s immigration file. National Archives: Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office

Figure 5. Signature of Wong Kim Ark, who confirmed that he was a U.S. citizen. National Archives: Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office

Wong Kim Ark and his lawyers tried to link Chinese Birthright Citizenship to that of thousands of white immigrant children. On March 28, 1898, in a 6-2 decision, the majority concluded that “subject to the jurisdiction” meant all native-born children, excluding only those who were born to foreign rulers or diplomats, born on foreign public ships, or born to enemy forces engaged in hostile occupation of the country’s territory, were citizens (1). Wong Kim Ark had finally acquired the citizenship that had long been denied to him.

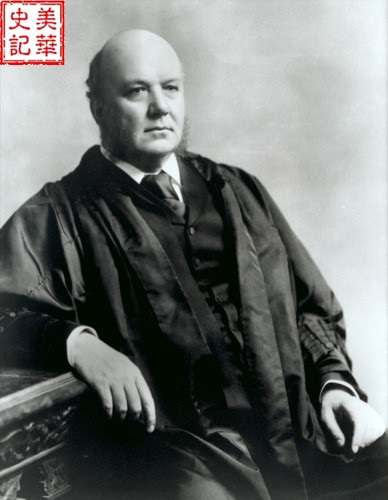

Picture 6. 1894 Supreme Court. Reproduced in Yarbrough, Tinsley E. Judicial Enigma: The First Justice Harlan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Figure 7. Associate Justice Horace Gray wrote the court opinion on the Wong Kim Ark case.

Figure 8. Chief Justice Melville Fuller wrote the dissent in the Wong Kim Ark case.

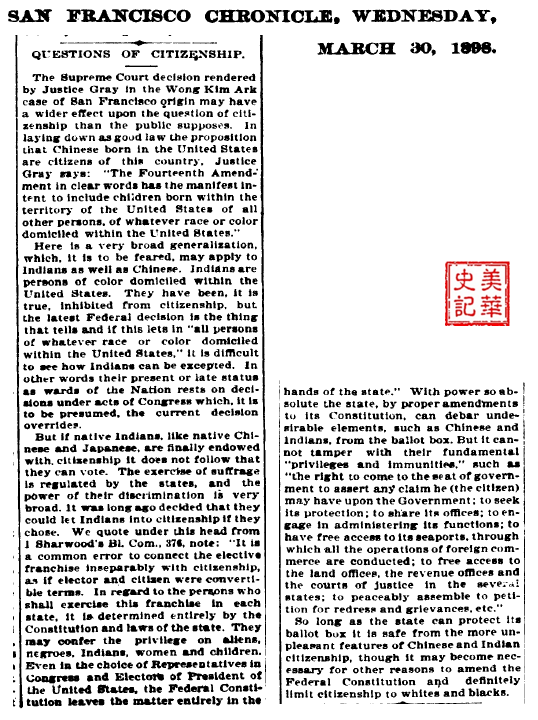

The San Francisco Chronicle published an editorial on March 30, 1898, expressing concern that the court decision could allow not only ethnic Chinese, but also ethnic Japanese and American Indians to become citizens, and possibly even allow them to receive the right to vote. It ended with a suggestion that it may become necessary to amend the U.S. Constitution and “definitely limit citizenship to whites and blacks.” (18)

Figure 9. “Wong Kim Ark” – San Francisco Chronicle, 1898-03-30.

Wong’s case has set a precedent for the children of all immigrants and significantly affected the U.S. immigration history, regarding the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and “Birthright Citizenship”. Since then, everyone born in the United States, regardless of race, color, or parental status, is eligible to be a U.S. citizen.

Since the 1990s, however, the long-standing practice of automatically granting citizenship to children of illegal immigrants born in the United States has caused widespread controversy, and legal scholars have disagreed on whether the Wong precedent applies to illegal immigrant parents (19). Congress has tried to pass legislation redefining the term “jurisdiction” to modify “Birthright Citizenship”.

Wong’s case set a precedent for the children of all immigrants and significantly affected the U.S.’s immigration policy. Since then, everyone born in the United States, regardless of race, color, or parental status, is eligible to be a U.S. citizen.

Recently, however, the long-standing practice of automatically granting citizenship to children of illegal immigrants born in the United States has caused widespread controversy, and legal scholars have disagreed on whether the Wong precedent applies to illegal immigrant parents (19). Congress has tried to pass legislation redefining the term “jurisdiction” to modify “Birthright Citizenship”.

Defending “Right of the Soil” and Violating “Right of the Blood”

After winning the case in the Supreme Court, Wong Kim Ark moved to Texas. In October 1901, immigration officials in El Paso, Texas, again jailed Wong Kim Ark. Wong, who had just won a Supreme Court case to prove his “American-ness”, was at risk of deportation again. After posting $300 bail, he was released. It took immigration officials nearly four more months to prove that Wong was a citizen entitled to remain in the United States. On February 18, 1902, the Government Commissioner, Walter D. Howe once again declared that Wong was a U.S. citizen and had the right to remain in his country (4).

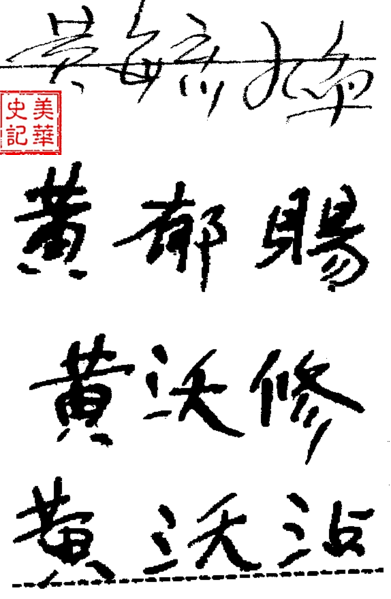

Wong did not dare to return to China for 7 years after acquiring his U.S. citizenship. His sons immigrated to the United States as U.S. citizens through “jus sanguinis, right of the blood”, between 1924 and 1926. The youngest son served during World War II and later worked in the U.S. Merchant Fleet for 25 years (8).

Figure 10. Signatures of Wong Kim Ark’s four sons: Wong Yoke Fun; Wong Yook Sue; Wong Yook Thue; and Wong Yook Jim. National Archives and Records Administration

A Startling Secret

Amanda Frost is a professor of law and government at the American University Washington College of Law. Her new book, You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers, uncovered an untold story of Wong Kim Ark and his family (20).

In March 2019, Professor Frost received an e-mail from an archivist filled with exclamation points. To Frost, this was a rare display of emotion from a man who worked with century-old documents in hushed rooms. What the archivist had discovered was that the record of Yook Sue, one of the sons of Wong Kim Ark, was missing in the immigration file. Instead, he found the record of Ernest J. Wong– with a startling secret inside (20).

Ernest Wong was a cook at the Drake Hotel in San Francisco’s Union Square. On October 18, 1960, he admitted to entering the United States fraudulently by claiming to be the son of Wong Kim Ark, “Wong Yook Sue”. Ernest Wong submitted an application to become a permanent resident of the United States, along with a confession statement (4).

Ernest Wong wrote (4), “I last entered the United States claiming to be WONG YOOK SUE, the citizen son of WONG KIM ARK,” but “I now admit that I am a citizen of China and that I have never been a citizen of the United States. … I am not related to my immigration father, WONG KIM ARK, in any way.” By this time, Wong had already returned to China and had died and been buried in his ancestral grave.

The irony is that the real eldest son of Wong Kim Ark, Wong Yoke Fun, was suspected of immigration fraud and failed to immigrate to the United States, while the “Paper Son” who had no father-son relationship with Wong Kim Ark succeeded. He later became the spiritual motivator of other “sons” to immigrate to the United States.

On October 28, 1910, Wong Kim Ark’s elder son, Wong Yoke Fun, arrived in San Francisco from China and was detained on Angel Island. Immigration officials questioned the father and son separately for several days in a cramped interrogation room to verify this fact. Because of the significant differences in the testimony of Wong Kim Ark and Wong Yoke Fun, a three-member committee unanimously ruled that they were not biological fathers and sons and that the applicant was suspected of fraud. As a result, Wong Yoke Fun was deported back to China on January 9, 1911. Wong Yoke Fun stayed in China for more than 10 years, until his younger brothers immigrated to the United States. Wong Kim Ark later returned home, and was finally able to reunite with Wong Yoke Fun in his hometown (4).

Thirteen years later, in 1924, another son of Wong Kim Ark’s, Wong Yook Sue, came to America–and underwent the same process– detention, interrogation, and repatriation. Wong Yook Sue, however, refused to be deported, opting instead to overturn the immigration officer’s decision with a legal process. His efforts paid off, eventually winning a lawsuit and staying in the United States as a U.S. citizen (20).

A year later, in March 1925, Wong Yook Thue, inspired by the success of the “Wong Yook Sue”, crossed the Pacific Ocean to enter the United States as a U.S. citizen. Another year later, Wong Kim Ark’s youngest son, Wong Yook Jim, who at the time was 11-years-old and 1.1-meters-tall (4-foot-2-foot), made it to the U.S (4, 20).

In the confession, Ernest Wong said, “I believe that WONG KIM ARK was actually born in the United States as he claimed,” and that “the third son, YOOK JIM, is a true son of WONG KIM ARK.” (4)

If not for Ernest Wong’s confession, people would have never known of Wong Kim Ark, who used the law (right of the blood) to help a “Paper Son” to immigrate to the United States. In this story we find a true record of the two sides of human nature. Justice and injustice are often intertwined in people’s life.

“Paper Son” and the Chinese Confession Program

The term “Paper Son” was specifically coined for Chinese immigrants who privately signed an agreement and paid a fee to become the son of a U.S. citizen to get into this country.

After Wong Kim Ark won the Birthright Citizenship, the U.S. born Chinese population grew rapidly in the 1890s. Due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was very difficult for Chinese people to get into the county. However, Chinese people looking to immigrate could take advantage of the 14th Amendment. A person could make a fake document to gain a Birthright Citizenship through “right of the soil”. The fire that followed the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco destroyed many immigration records, so almost all Chinese in the United States at the time could claim that they were born in the United States. In 1901, a federal judge noted, “If all the stories told in the court were true, every Chinese woman who was in the United States 25 years ago must have had at least 500 children.” (21)

After acquiring citizenship through “right of the soil”, these citizens could apply for citizenship for future generations through “right of the blood”. There were well-organized illegal immigration smuggling networks in the Chinese community, which forged documents and sold slots. Papers could cost $100 for each year recorded, so for example, a 20-year-old “Paper Son” would need $2000. But if the “Paper Son” managed to successfully enter the country and get a job in the U.S., he could pay off his debts in as little as two years. Smugglers would find those willing to buy “Paper Son” slots, ask for details such as age, gender, dialect, and so on, and then match each parameters. In addition, they provided a guidebook or shorthand manual to prepare the “Paper Son” for interviews by the Immigration Department (21).

In 1955, Everett F. Drumright, the U.S. consul in Hong Kong, submitted an 89-page white paper to the State Department, claiming that almost all Chinese entering the United States were illegal immigrants. He pointed out that a large number of Chinese-Americans entered the country “legally” as sons of citizens. What’s more, he asserted that the Chinese Communist Party was likely to exploit loopholes in the system to send spies to the United States. J. Edgar Hoover raised the Red-baiting bar in 1955 when he testified to the Senate, “The large number of Chinese entering this country as immigrants provides Rad China with a channel to dispatch to the United States undercover agents on intelligence assignments.” According to U.S. News and World Report, “Thousands of Chinese in recent years have obtained illegal entry into the U.S. by posting as the sons of Chinese who were American citizens. Many who entered this way were red agents.” (22) At the time, these statements were very much on the air.

Figure 11. Everett Francis Drumright (September 15, 1906 – April 24, 1993) was an American diplomat. He served as Ambassador of the United States to the Republic of China (Taiwan) from March 8, 1958 to March 8, 1962. He was a member of the Board of Directors of the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.

In 1956, the U.S. Immigration and Neutralization Service (INS) launched the “Chinese Confessions Program”, in which the federal government encouraged Chinese people who fraudulently obtained U.S. citizenship to come forward. Before making the confession, an individual had to surrender and officially sign all documents of citizenship over to the INS. Officers also required the confessors to state that they were “amenable for deportation” if their confession was denied. The INS only launched the confession program but did not have official statute governed the process and specific legal provisions for the amnesty of “confessors” (22).

Figure 12, In 1959, the United Press reported that the “Chinese Confession Program” has approved remarkably successful in thwarting the illegal of Chinese aliens into the United States.

The program affected a huge number of Chinese people between 1957 and 1965. Many of them lived under a dark shadow, not knowing who was telling what and on whom to the authorities. By 1965, when the program finally ended, 13,895 people had confessed, exposing 22,083 others and resulting in the closing of 11,294 potential “Paper Son” slots (22).

Like many others– half the whistleblower, half the confessor– Ernest Wong was accused of immigration fraud, so he confessed that Wong took money from his biological father to help him immigrate to the United States (4).

Half the victim, half the accomplice, Wong was initially denied his citizenship because his biological parents were Chinese. He defended himself with indomitable courage and resilience, and finally won his citizenship. Yet he also violated the immigration law to bring in a “Paper Son.”

Like everyone else, many Chinese immigrants had to go through an unusual path and take risks, often resorting to illegal means, to obtain U.S. citizenship in the era of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This is the true history of Chinese immigration history, with all its sorrows and tears.

In 1932, in his twilight years, Wong Kim Ark returned to his home in Guangdong and reunited with his wife, whom he had been separated from for decades, and his bones were eventually buried in the family cemetery with his ancestors (4).

A person, a story, a history, a kind of bitterness, right and wrong…

References:

1, United States Supreme Court: United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 18 S. Ct. 456; 42 L. Ed. 890; 1898 U.S. LEXIS 1515 (1898), Appeal from the District Court of the United States for the Northern District of California; 71 F. 382.

2, Lisa Davis. “The Progeny of Citizen Wong”. SF Weekly. Retrieved July 17, 2011. “Wong Kim Ark spent most of his life as a cook in various Chinatown restaurants. In 1894, Wong visited his family in China.” November 4, 1998

3, Jean Pfaelzer. Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans. University of California Press. 2008. P89-120.

4, Amanda Frost. You Are Not American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers. Beacon Press. 2021. P51-73

5, Public law 43–141. 18 Stat. 477, Chap. 141

6, George Anthony Peffer, “Forbidden Families: Emigration Experiences of Chinese Women Under the Page Law, 1875-1882,” Journal of American Ethnic History 6.1. Fall 1986. P28-46.

7, Kerry Abrams. Polygamy, Prostitution, and the Federalization of Immigration Law. Columbia Law Review. 105.3, Apr. 2005, P641-716.

8, Philip A. Kuhn, Chinese among others: emigration in modern times. Phoenix Publishing and Media Group. P19-20。

9, Bethany Berger. Birthright Citizenship on Trial: Elk v. Wilkins and United States v. Wong Kim Ark. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2610859

10, UNITED STATES v. WONG KIM ARK. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/169/649

11, Lucy E Salyer. Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship. In Martin, David; Schuck, Peter (eds.). Immigration Stories. New York: Foundation Press. ISBN 1-58778-873-X. 2005.

12, United States District Courts: In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. 382 (N.D.Cal. 1896)

13, Marshall B Woodworth. “Citizenship of the United States under the Fourteenth Amendment”. American Law Review. 1896. http://faculty.law.miami.edu/zfenton/download/woodworth32amlrev554.pdf

14, State courts: Lynch v. Clarke, 3 N.Y.Leg.Obs. 236 (N.Y. 1844)

15, United States Supreme Court: Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 1857.

16, Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) “Constitution of the United States: Amendments 11–27”. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

17, Anne Cooper Kelley, Lorraine Hee-Chorley. Discovering family ties at the Chinese temple in Mendocino. Ukiah Daily Journal. 2 September 2017.

18, Chuck Marcus. Wong Kim Ark’s Case. http://libraryweb.uchastings.edu/library/research/special-collections/wong-kim-ark/case.htm

19, “Questions of Citizenship”. San Francisco Chronicle. March 30, 1898. P6.

20, James C Ho. Defining ‘American’: Birthright Citizenship and the Original Understanding of the 14th Amendment. 2006. https://www.gibsondunn.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/publications/Ho-DefiningAmerican.pdf

21, Amanda Frost. Birthright Citizens and Paper Sons. The complicated case of an American-born child of Chinese immigrants. American Scholar. January 18, 2021.

Birthright Citizens and Paper Sons

22, Peter Kwong, Kusanka Miscevic. Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Commiunity. New Press, New York, London, 2005: P138-141.

23, Peter Kwong, P223-226.

Pingback: White Paper: National Museum of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders – 美华史记