Author: Zhida Song-James

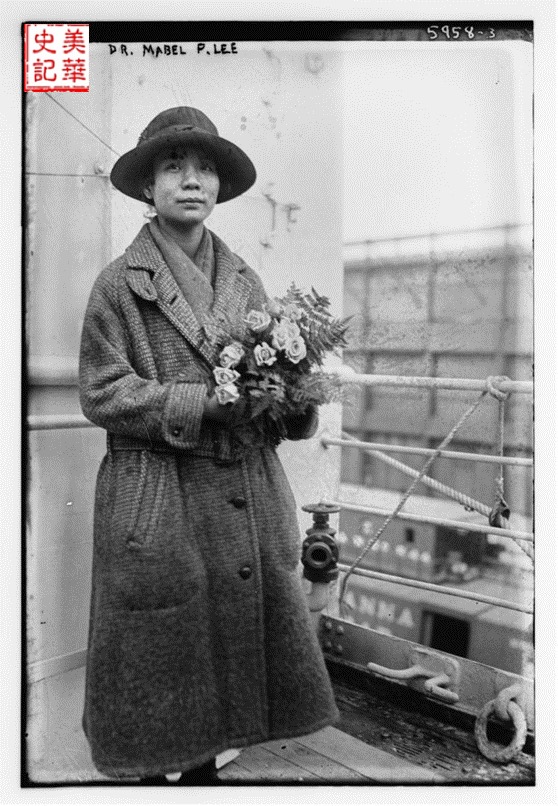

On May 4, 1912, tens of thousands of New Yorkers gathered in the streets of Greenwich Village, and the march for women’s suffrage was about to start. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a young Chinese woman, was on horseback leading the procession. It was one of the largest gatherings of US women’s political participation. Although, as a Chinese, Mabel could not apply to become a US citizen under the discriminative immigration laws at the time, she played an important role in women’s prolonged fighting for the right to vote in the United States from a young age. Later, she became the first Chinese woman to receive a doctorate in the United States. Today, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee is recognized as a pioneer for Chinese women to participate in women’s rights movements in the United States.

Let’s briefly review the living environment from the perspective of female Chinese immigrants in 1912.

Since 1875, the US Congress had passed two strict immigration laws that discriminated against the Chinese, and the first victims were Chinese women. The Page Act, passed in 1875, falsely assumed that all Chinese women who came to the United States engaged in “immoral trades,” which violated American society’s morals and undermined American families. It banned Chinese women from entering the country. With such restriction, the Page Act effectively eliminated the possibility of male Chinese immigrants starting families in the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 drastically reduced the number of Chinese immigrants allowed to enter the United States legally. It forbade Chinese immigrants to apply for naturalization to become American citizens. In 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was supposed to renew every ten years, became the permanent law of the land. Chinese women faced double discrimination and oppression due to race and gender.

Mabel was born in 1897 in Guangzhou, China. 1 Her father, Towe Lee, was a teacher working at a Christian school run by a US Baptist Mission. With the help of the Mission, he became one of the very few Chinese who were able to come to the United States during the Chinese Exclusion Act. Mabel arrived in the United States at nine with his mother, Lee Lai Beck (also recorded as Lennick Lee or Libreck Lee in the different census). By then, his father was a missionary at the Baptist Morning Star Mission in New York’s Chinatown. 2 As the only child of two teachers, Mabel initially received her traditional Chinese education in China. After coming to New York, her parents sent her to Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn. When she graduated, she was the only Chinese student in her class. It was in Erasmus where she was first exposed to the women’s suffrage movement and soon became an active member.

Who Has the Right to Vote in the United States in 1912?

Voting is one of the fundamental rights of a citizen of a country. Since British and other European immigrants came to Northern America in the 17th century and established the first thirteen colonies, who could vote was a gradually developed process. In 1776, the thirteen colonies declared independence; in 1789, the nascent United States passed the first Constitution. However, it did not define voting eligibility nationwide but gave the decision power to states. 3 Most states then granted the voting right to European male immigrants who owned sufficient property and paid taxes. There were only 6% of the total population met the criteria. Some states did not specify race, which let free black males who owned enough properties vote too. 4 However, all women, like men with no property, were not eligible to vote. 5 From 1792 onwards, property claims were gradually abolished, and more whites were granted voting rights.

After the Civil War, the United States went through a critical reconstruction period. In 1868, Congress passed the historic Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which established equal rights for all persons born or naturalized in the United States, laying the groundwork for expanding suffrage to all citizens. Two years later, in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment extended the right to vote to all citizens, making it clear that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged on account of race, color, or previous conditions of servitude.”

At this time, however, women were still excluded from citizens with the right to vote. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the forerunners of the women’s rights movement had made suffrage a central part of women’s political participation; the first National Congress of Women’s Rights was held in 1850, and the American Equal Rights Association was established in 1866. The leaders increasingly made it clear that without women’s suffrage, all citizens would not have equal rights. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), founded in 1890, became a central force leading the movement. In 1909, the Women’s Suffrage Party (WSP) was founded as a political coalition of women’s equal participation in New York City. The WSP offered opportunities for many New York women to exposure to politics; Mabel Lee was one of them. This organization was very active and directly contributed to the subsequent passage of an amendment to the New York State Law which granted women suffrage.

What Happened in China in 1912?

China, in 1912, was experiencing the most significant turning point in its long history. On October 10, 1911, the sound of gunfire in the City of Wuchang opened a new era for this ancient nation. The Xinhai Revolution (or 1911 Revolution) overthrew the rule of the Qing Dynasty and ended China’s imperial governing since 221 BC. Led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, China broke away from the shackles of the feudal dynasty and began to move toward a republic. This revolutionary movement has received extensive support among overseas Chinese. Before 1911, Sun Yat-sen had traveled overseas to promote the concept of establishing a democratic republic tirelessly. He received enthusiastic support and donations from Chinese communities in the US. After firing the first shot of the Xinhai Revolution, many overseas Chinese organizations declared their support by sending open telegraphs and publishing articles in newspapers. Witnessed the tremendous contributions made by overseas Chinese to the revolution, Sun Yat-sen once said that there would not be the Republic of China without overseas Chinese. The success of the Chinese revolution also encouraged Chinese immigrants in the US: Chinese people were no longer ruled by an emperor with absolute power. On January 1, 1912, Sun Yat-sen officially proclaimed the establishment of the Republic of China in Nanjing and was sworn in as its Provisional President.

With the fall of the Empire, Chinese women, who had been at the bottom of society, rose to fight for equality between men and women. Women educated abroad were the first to speak out in favor of the republic, emphasizing that in a republic, men and women should have equal rights and obligations. In a meeting with Ms. Lin Zongsu, the leader of the newly emerged women’s rights movement, Sun Yat-sen expressed his approval of women’s full participation in society. On April 8, 1912, the Women’s Political Participation League of the Republic of China was founded in Nanjing, and Ms. Tang Qunying was elected as its President. The purpose of the Association was to “practice equality between men and women and to participate in politics.” The organization formulated eleven political platforms for women’s equal rights.

The news spread overseas; together with the surging suffrage in the United States, it stirred up big waves in the heart of Mabel Lee, who faced racial and gender discrimination. It became a powerful driving force for her to join the movement fighting for women’s equal rights and political participation.

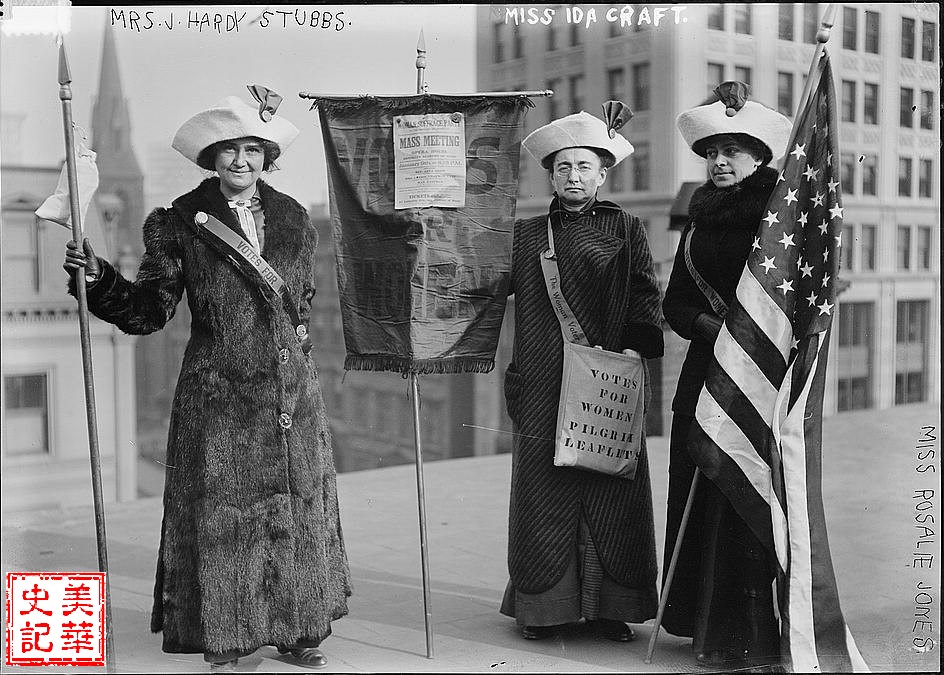

Jointly Strive for Women’s Suffrage

The news that Chinese women were about to receive full rights for political participation was like a thunderclap that greatly shook the leaders of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States. Once China, a country where feudal dynasties had ruled for over two thousand years, moved towards a republic, it actually got ahead of the United States regarding women’s suffrage. The leaders thought they must seize this opportunity to push the movement further. The Chinese community, struggling to survive under a series of discriminative exclusion laws, also believed it might be an opportunity to fight against discrimination and for the equal right to pursue citizenship.

In 1912, female Chinese activists in Portland, Cincinnati, Boston, New York, and other cities were invited to address National Women’s Suffrage Federation meetings. They took this rare opportunity to share the news about Chinese women’s contribution to overthrowing feudal rules and establishing a new state. They told the American sisters about the heroic women who fought side by side with men in the armed uprising that led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty and envisioned the future of Chinese women as equal citizens in the newborn republic. Although there have been twists and turns in Chinese women’s political participation since then, this initial progress was very encouraging. They called on the white women attending the meetings to uphold justice, lend their helping hands, listen to the needs of the Chinese community in the United States, and support the overthrow of immigration laws that discriminate against Chinese immigrants.

National Women’s Suffrage Federation was preparing to hold a big march in the Spring of 1912; leaders in New York City were keenly aware that the progress the women in China achieved could be the main point attracting more attention. They met with Mabel Lee and other Chinese community leaders at Peking Restaurant at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 47th Street. The attendees were Harriet Laidlow, a prominent leader of the women’s suffrage movement; Anna Howard Shaw, the President of the Manhattan chapter of the Women’s Suffrage Party; and Alva Belmont, the President of the National Federation of Women’s Suffrage and one of the principal patrons of the feminist movement. In addition to Mabel Lee and her parents, businesswoman Grace Yip Typond and a female teacher Pearl Mark Loo also attended. Sixteen-year-old Mabel Lee pointed out to these white leaders that Chinese women suffered not only from gender discrimination as other American women did but also from racial discrimination. Most Chinese youth, both men and women, did not have equal access to education opportunities. Pearl Mark Loo exposed the harsh and unfair treatment of legal immigrants by US immigration officials, using her personal experience as an example. She stressed that the United States should give Chinese immigrants equal rights. The New York Endowment Tribune reported the story, which described Mabel Lee as “Chinese Girl Wants Vote” in its headline.

On the day of the parade, Mabel Lee was in front, leading the entire crowd. Her mother and Chinese women from Chinatown walked arm-in-arm, holding China’s five-color republic flag and a sign with the slogan “Light of China.” Anna Howard Shaw, President of the Manhattan chapter of the Women’s Suffrage Party, walked ahead of the Chinatown ranks holding a banner of “Women’s Suffrage Federation Catches Up with China.” Like most Americans, New Yorkers generally believed that the modern United States was ahead of China in all respects of life and that American culture was superior to China’s. In contrast, her banner declared the opposite: in the stage of women’s political participation, the United States lagged and must catch up. As expected, such a statement shocked onlookers. Suffrage activists hoped this shock would encourage more people to participate or support their efforts and make women obtain equal voting rights soon. The Chinese also took the opportunity to declare that China was no longer a feudal empire and that a republican China was emerging on the world stage with a new look. They hoped this would break the public stereotype and thus prompt the US government to change its discriminatory policy against Chinese immigrants.

In the fall of 1912, Mabel Lee entered Barnard College, a private woman’s liberal arts college affiliated with Columbia University. During her studies, she followed suffrage in the United States by writing articles, giving speeches within and outside the school, and participating in activities promoting women’s equal rights. In addition, she had never forgotten the women’s rights progress in China and was involved in activities of students from China.

In 1908, the United States established a $17 million Boxer Indemnity Scholarship for students from China, aimed to train China’s future political, industrial, and business leaders through US education. The first batch of recipients arrived in the United States in 1909. Mabel Lee herself later became one of the scholarship winners. These students organized a nationwide organization of the Chinese Students Federation and published periodicals for its members. Realizing their influence on China’s future, Mabel wrote an essay entitled “The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage” 6 published in the journal in 1914. She stated that women’s rights should be integral to the new national structure. The feminist movement was not advocating for “women’s privileges” but “the requirement of women to be worthy citizens and contribute their share to the steady and progress of our country.”

Two years later, she gave a lecture at a Women’s Political Union symposium titled “The Submerged Half.” She encouraged women of all ages in China to pursue education and civic activity, saying that “no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization unless its women are following close to its men if not actually abreast with them.” 7 She did as she said; she not only continuously contributed to women’s suffrage but was also active in the Chinese Student Federation. She ran for its President in 1916, only lost to her tough opponent, T.V. Soong. 8

After graduating from Bernard College, Mabel studied at the Teacher’s College of Columbia University and earned a master’s degree in educational management. She then began her Ph.D. studies in the history of economics; during this period, she met and developed a friendship with Hu Shih, who was also studying at Columbia. Years later, Hu Shih, who had become a leading scholar, dedicated his prestigious Haskell Lecture to Mabel Lee at Oberlin College. 9

In 1917, New York State granted women’s suffrage. The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1920, prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States based on sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. But the Nineteenth Amendment did not fully grant the same rights to ethnic minorities such as African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanics, and Indigenous women. Shortly after the amendment was adopted, the National Women’s Suffrage Federation began working on the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which they saw as the next step toward full gender equality.

A year later, in 1921, Mabel earned her Ph.D. in Economics from Columbia University, becoming the first Chinese woman to receive a Ph.D. in the United States. Her doctoral dissertation, The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture, was soon published. 10 Despite such an outstanding achievement, Mabel Lee still was not allowed to apply for citizenship and still did not have the voting right. In 1924, US Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which further restricted immigration from Asia and set quotas for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere. Chinese community’s efforts to get assistance from women’s rights activists to fight against the racial-based immigration restrictions once again hit a wall. This barrier was not broken until 1943. When China and the United States were fighting against Japan shoulder by shoulder during World War II, and many young Chinese immigrants were shading their blood to defend the US, Chinese living in the US were finally able to apply for citizenship.

Although holding her doctorate, Mabel could not obtain a teaching position in the United States. In contrast, most 53 female Boxer Indemnity Scholarship recipients returned to China and became pioneers in their fields. Among them were professors, medical doctors, physicists, journalists, musicians, and a pilot.11 Each made significant contributions to China’s development. If it were not due to the double discrimination of race and gender, Dr. Mabel Lee would have had a good chance of becoming a prominent economist.

Serving Chinese Church and Community

Mable Lee returned to the Chinese community where she grew up, working as a manager at the First Chinese Baptist Church in New York, where her father, Towe Lee, was a pastor. By this time, her father had become President of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society in Chinatown. Mabel did not give up her hope of working in higher education institutes; she traveled to China and Europe to explore. She had an opportunity in China: the University of Amoy invited her to take a position as the dean of its Women’s College. However, Pastor Towe Lee died of a heart attack while settling a dispute between two rival tongs in Chinatown. The American Baptist Home Mission Society, to which his church belongs, appointed Mabel as his successor to take overall administrative responsibility for the church. From then until 1930, Mable maintained contact with Columbia University and visited China several times to experience the environment and explore opportunities. Due to various reasons, she finally gave up the consideration of teaching in China; instead, she decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and serve wholeheartedly in the Chinese church he had founded.

In addition to the daily work of the church, Mabel Lee raised funds from the New York chapter of the Baptist Family Missionary Association and Chinese communities, bought a house, and opened the Chinese Christian Center. This community center provided much-needed community services: it operated a health clinic and a kindergarten; it offered vocational training and English courses to help the Chinese, especially newcomers, enhance their ability to survive in the United States. Her friend Dr. Hu Shih, who had supported her for years, served on the Center’s Board.

Mabel had a plan that her church would become economically self-sufficient and fully administrated by Chinese Christians. She worked hard to break away from the white-led national church organizations. Finally, the church split off and became the First Baptist Church of China; Mabel Lee independently assumed the responsibility of keeping the church running.

During World War II, the generation that grew up in the church either joined the military or got jobs elsewhere, and many left Chinatown. Some church members disagreed with her vision and how to manage the church and chose to leave. The younger Chinese became more and more secularized. All of these led to a continuous decline in church membership. However, the activities of the Community Center never stopped. Fluent in Chinese (Cantonese) and English, Mabel Lee could access all groups of the Chinese community. Under her leadership, the Center continuously provided language and a variety of vocational education courses, including typing, carpentry, early childhood education, etc. Such activities complemented the social services the city government failed to provide the Chinatown community. The Center played a crucial role in helping later immigrants. Mabel served in the church and community until her death in 1966 at the age of 70. The Community Center still exists today.

Decades have passed, but Mabel Lee’s contribution to women’s suffrage and her lifelong services to the Chinatown community have not been forgotten. In 2018 Nydia Velázquez, the congresswoman in New York’s 7th District, introduced legislation to name the Chinatown Post Office, located near the church, the Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office. It was signed into law by President Trump. In the dedication ceremony, Velázquez said: “At a time when women were widely expected to spend a life in the home, Lee shattered one glass ceiling after another. From speaking out in the classroom to organizing Chinese-American women to secure the right to vote, Lee’s bold vision for Chinatown is very much alive in our community today.” 12

We do not know for sure whether Mabel Lee became a US citizen and exercised her right to vote during her lifetime. Still, she played a unique role and significantly contributed to American women’s fight for the right to vote. As a Chinese woman, she and her peers spread women’s advocacy for equal political rights in the newly founded Republic of China to the United States, opening the door for suffrage leaders to promote the movement from another perspective. Mabel and her peers claimed that the pursuit of equal rights is not limited to gender but must include race. Her influence extended far beyond the Chinese community. Her actions inspired many later women to join the movement, eventually prompting women of all ethnicities in the United States to gain the right to vote. She represents the earliest Chinese women to participate in politics and is the forerunner of the countless women who continue to oppose gender and racial discrimination today.

References

- Kerri Lee Alexander, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1897-1966), Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mabel-ping-hua-lee

- Cathleen D. Cahill, Mabel Ping-Hua Lee: How Chinese American Women Helped Shape the Suffrage Movement, National Park Service, Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/mabel-ping-hua-lee-how-chinese-american-women-helped-shape-the-suffrage-movement.htm

- The Constitution, The White House, Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/our-government/the-constitution/

- Hanes Walton Jr, Sherman C Puckett, Donald R. Deskins eds., The African American Electorate: A Statistical History (CQ Press), 2012, P84.

- The Founders and the Vote, Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/elections/right-to-vote/the-founders-and-the-vote/

- Mabel Lee, The Meaning of Woman’s Suffrage, The Chinese Students’ Monthly, May 1914, P526-531.

- Timothy Tseng, Dr. Mabel Lee: The Interstitial Career of a Protestant Chinese American Woman, 1924-1950, paper presented at the Organization of American Historians Meeting, 1996, P5. Accessed July 15, 2022. https://timtsengdotnet.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/mabel-lee-paper-1996.pdf

- Ibid. P5

- Ibid. P1

- Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, The Economic History of China: with Special Reference to Agriculture. (AMS Press New York), 1921.

- 王晓慧 ,全球史视野下的清华专科女生留美教育述略,首都师范大学全球史中心,Accessed July 14,2022. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzUzOTgxODQyMg==&mid=2247484281&idx=1&sn=a73f258bb37fd69fb62afffa6b95df6f&chksm=f

- USPS News, New York News, November 27, 2018, Accessed July 14, 2022. https://about.usps.com/newsroom/local-releases/ny/2018/1127-mabel-lee-memorial-post-office-dedication-ceremony.htm