Fan Jiao

The three amendments (Amendments 13, 14, 15) adopted after the American Civil War (1861-1865) to abolish slavery and establish civil and legal rights for black Americans,among which, the 14th amendment established in 1866, granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including former slaves, and guaranteed that all persons can be protected by law on an equal footing. This Amendment and its “Equal Protection Clause,” which states that “any person within its jurisdiction is equally protected by law,” has been the basis for many landmark rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court over the years.

The judgment of Yick Wo v. Hopkins on May 10, 1886 is one of the twenty-five most influential cases of SCOTUS, and more than 160 subsequent cases have cited this landmark case that was the first time based on the 14th Amendment.

In a 2018 speech on “The Importance of the Yick Wo Case,” former Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy said, “We would like to thank Yick Wo, who was not a U.S. citizen, for coming to the U.S. Supreme Court to help us establish this important indoctrination.” 1

The laws targeting Chinese immigrants in CA after 1850

In the 1850s, the United States was still a young country and lacked labor. Chinese immigrants came to the western part of the United States by steamboats to work in the gold panning and played an important role in creating the Transnational Railway. At the same time, European, and Latino immigrants from the east and west regions to immigrate to the U.S from land.

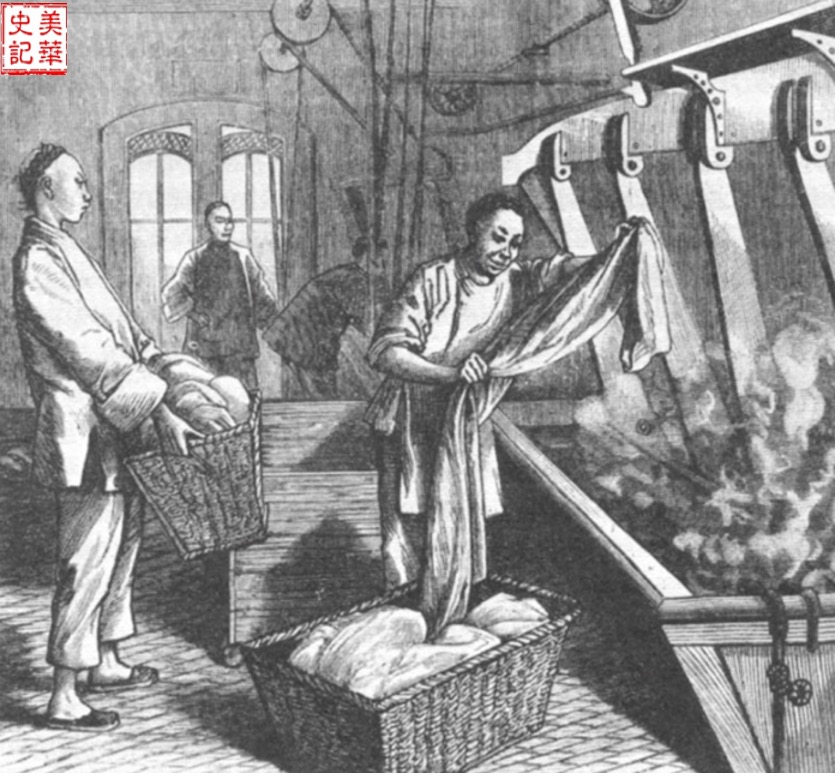

Gradually, many Chinese came to settle in San Francisco one after another, accounting for about 10% of the city’s population2. They worked hard and in some operations such as hand laundromats that didn’t use traditional dryers; rather, by natural drying from cool air such that the cost was lower. They became a new immigrant group to compete with the existing population in terms of employment.

In 1852, California passed a foreign miner license tax, requiring foreigners who were not U.S. citizens to obtain a license in 1870 for extra $3/month. Over the next 20 years, this tax was gradually increased, reaching $20 a month in 1870.

In 1855, San Francisco issued a decree that everyone who landed on a steamboat (meant by Chinese) had to pay a tax of $50.

In 1860, California enacted a law that Chinese fishmen must pay a special tax. San Francisco had passed a law banning Chinese children from attending public schools. San Francisco City Hospitals refused to admit Chinese patients.

The California Police Tax was passed in 1862, requiring every Chinese over the age of 18 who was not employed in California rice, sugar, tea, or coffee industries to pay an additional $2.50 per month in tax.

An 1870 San Francisco ordinance mandated that each rental house must have at least 500 cubic feet of space to limit family size. Another ordinance prohibited the use of poles to sell vegetables (a common practice for Chinese merchants to sell vegetables).

A state law passed by the California Supreme Court in 1873 ruled that Chinese people could not testify against Caucasians in court. San Francisco passed an ordinance that taxed laundromats $4 per horse ride delivery, while those without vehicles were taxed $60 per year. 3

The case of Vick Wo v. Hopkins

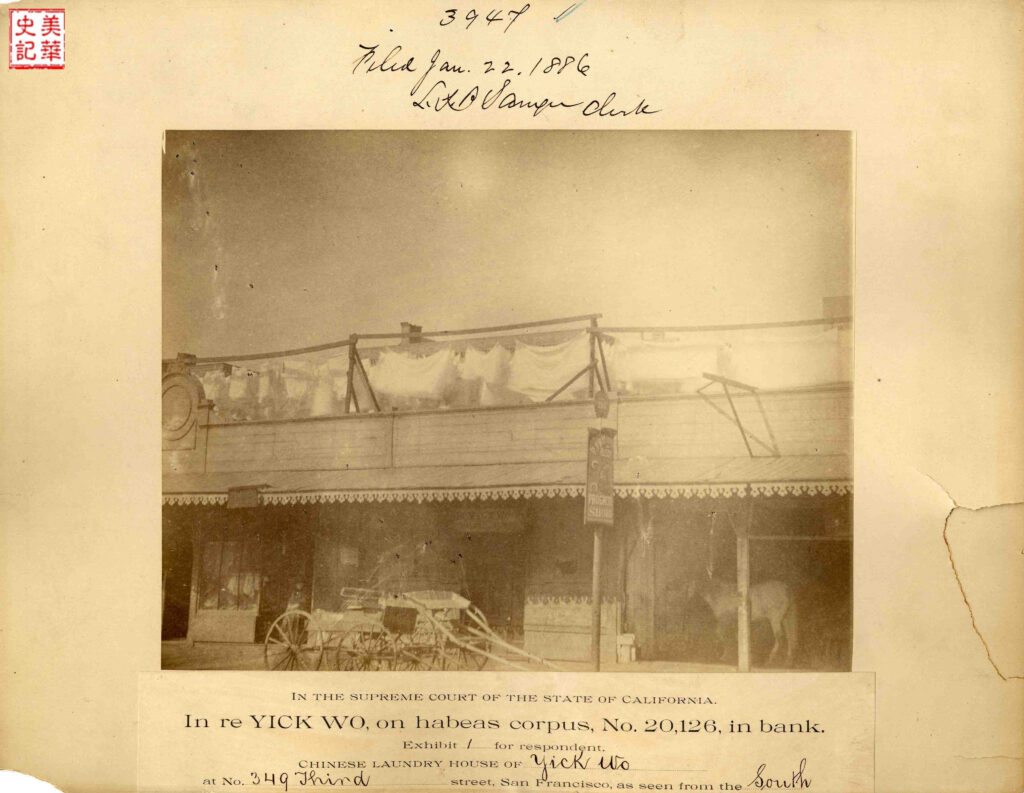

Yick Wo was a laundromat owned by Chinese immigrant Lee Yick in San Francisco, California, in 1880s.

In 1880, San Francisco passed laundromat legislation requiring the following articles:

- All laundromats must pass inspection by the city’s firefighters and the Sanitation Department and be approved by the Board of Supervisors to receive a license to operate.

- Since and after the passage of this order, except for laundromats in masonry buildings, unless prior consent of the Board of Supervisors has been obtained, any person or persons establishes, maintains, or operates a laundromat within the city and county of San Francisco on corporate grounds are illegal.

- Any person who erects, constructs, or maintains a rack for drying clothes on or on the roof of any building which may be constructed now or hereafter within the limits, erects or uses such scaffold without the written permission of the Supervisory Board; all are illegal.

- Any person who violates any provision of this order shall be considered a misdemeanor and shall, upon conviction, be liable to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, or imprisonment in the county jail. Not exceeding six months, or fines and imprisonment.

At that time in San Francisco, the Chinese owned more than two-thirds of the wooden laundromats with racks for drying clothes on the top floor (the laundries in the masonry buildings were all owned by whites). Ostensibly these decrees didn’t target any race, but they were known to be targeted at Chinese laundromats.

Then in San Francisco, there were 200 Chinese-run wooden laundries and 80 Caucasians owned wooden laundries. All but one of the white shops had obtained business permits. Even though they all passed inspections by city firefighters and health bureaus, none of the Chinese laundromats had obtained such permits. More than 150 of them continued to operate, and they were all arrested and jailed by the San Francisco Police Department.

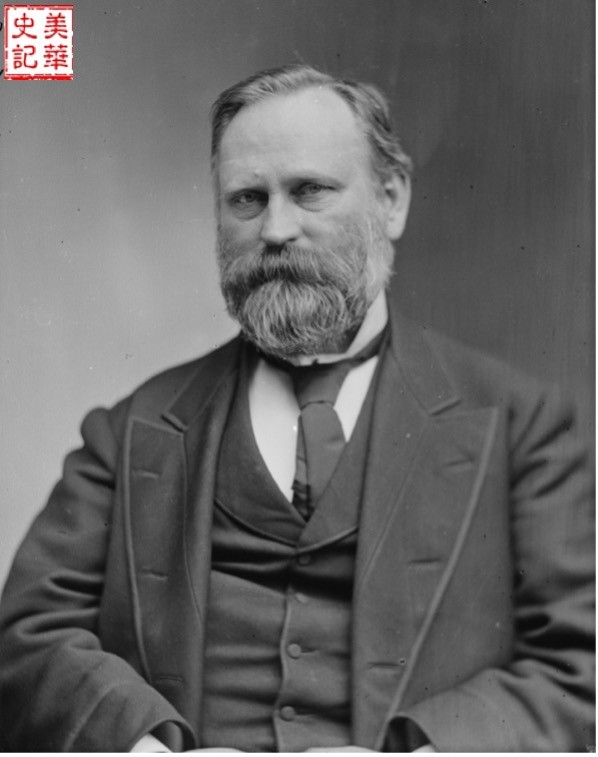

Sheriff Peter Hopkins (served from 1885-1886) fought in the Mexican War of 1846 and served as the city’s fire commissioner. He was responsible for arresting Yick Wo and more than 150 other Chinese who opened their business without a permit.

Among those more than 150 people in prison, Yick Wo vaguely knew that non-citizens were supposed to be protected by American law and sued police officer Peter Hopkins in the California Supreme Court for unfair law enforcement while in the prison. Soon the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of the sheriff, and Yick Wo refused to accept it and began to prepare to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Then another appellant, Wo Lee, went to the California Circuit Court, and Circuit Judge Sawyer saw the essence of the problem, stating in his opinion, “The petition shows that, in fact, all Chinese petitions were denied, Most Caucasian application were granted. So, in fact, the city discriminated against in the administration of the ordinance where the terms of the ordinance allowed it.” Sawyer then learned that Yick Wo was preparing to appeal to the Supreme Court. The two cases were virtually to be the same case; a Yick Wo’s victory was to “kill two birds with one stone”, so he intentionally sided with the Sheriff. Yick Wo hired a prominent attorney at the time, former California Circuit Judge Matthew Hall McAllister to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court (currently his statue stands in front of the San Francisco Civic Center, and McAllister Street next to the City Hall is named after him).

On April 14, 1886, Hall McAllister appealed to Supreme Court in habeas corpus on behalf of Yick Wo and Wo Lee alleging that the discriminatory enforcement of the San Francisco Laundry Ordinance violated their rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court ruled on May 10, 1886, that Associate Justice Thomas Stanley Matthews wrote the unanimous opinion on behalf of the court: “The law of ostensible neutrality, unequal enforcement violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees the equal application of the law. While the ordinance did not target Chinese laundries, statistics on how it was enforced indicated that it ended up being a racially discriminatory law, and thus unconstitutional, in violation of this part of the 14th Amendment:

No state shall make or enforce any law limiting the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; no state shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny that any person within its jurisdiction is equal to the laws protect. “4

The ruling makes Yick Wo the first case to use the Equal Protection Clause to strike down a law that may apply to everyone but is enforced unequally.

Soon, Yick Wo and Wo Lee were set free and were given a business permit to operate their wooden laundromats. 5

Chinese Fought back Discriminations and Benefited all Americans

“Yick Wo’s case is that enforcing the law with an evil eye, or an unequal hand violates the right to equal protection,” former Justice Anthony Kennedy pointed in a 2018 talk in the Yick Wo v. Hopkins.1

But that’s not the only precedent set by this extraordinary case; Yick Wo was not a U.S. citizen by law due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; however, the court ruled that his rights were still protected by the 14th Amendment, which states that no state may “deny grant its jurisdiction” equal protection of the laws of any person“, not just limited to the protection of citizens.

Since the case was decided in 1886, the Supreme Court alone has cited the decision in more than 160 opinions.6

The 1956 case of Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, held that defendants could not be denied appeal because of inability to pay for trial records.7

In Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 6-3 decision in 1965, the Supreme Court affirmed the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision that racial disparities in juries and the absence of any black jurors for a decade none of the evidence serving at the trial was sufficient “to establish prima facie evidence of unfair discrimination under the Fourteenth Amendment.”8

In 1982 in Plyler v. Doe 457 U.S. 202, the Supreme Court struck down a State of Texas law that barred illegal aliens from entering public schools. In its judgment, the court held that “in this case, the plaintiff, illegal alien, challenged the statute to claim the benefit of the equal protection clause, which states that no state may deny equality of law to anyone within its jurisdiction. protection, illegal aliens are people too. The undocumented status of these children cannot be a reasonable basis for denying them benefits.”9

Conclusion

Yick Wo v. Hopkins counter punched the discrimination against Chinese by the San Francisco government in the mid-nineteenth century and became an extraordinary case based on the 14th Amendment benefiting of all U.S. residents. The 14th Amendment will continue to be the basis for numerous civil rights laws such as interracial marriage, segregated schools, voting rights, disability rights, sex discrimination, college admission, and so on that the Supreme Court and other states would be ruled on in the future.

References:

- Yick Wo and the Equal Protection Clause, Annenberg Classroom, The Annenberg Public Policy Center, last accessed: 4:13pm,7/22/2022, https://www.annenbergclassroom.org/resource/yick-wo-equal-protection-clause/, https://assets.annenbergclassroom.org/annenbergclassroom-doc-yick_wo.mp4 19:07/20:10

- Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Demographics of San Francisco, last accessed 8/16/2022, https://usa.ipums.org/usa/

- The Chinese Experience in 19th Century America,Illinois Teaching Resources, The University of Illinois, 2006, last accessed:8:47am,7/20/2022, http://teachingresources.atlas.illinois.edu/chinese_exp/resources/resource_2_4.pdf

- Opinions/Syllabus, Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 366(1886) JUSTIA, US Supreme Court, last accessed:4:20pm, 7/22/2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/118/356/

- Annenberg Classroom, The Annenberg Public Policy Center, last accessed: 4:24pm,7/22/2022, https://www.annenbergclassroom.org/resource/yick-wo-equal-protection-clause/ https://assets.annenbergclassroom.org/annenbergclassroom-doc-yick_wo.mp4 first 15 mins of the video, 20:10

- Yick Wo and the Equal Protection Clause, The Constitution Project, last accessed: 4:41pm, 7/22/2022, https://www.theconstitutionproject.com/portfolio/yick-wo-and-the-equal-protection-clause

- Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, Court Listener, last accessed:6:23pm, 7/22/2022, https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/105382/griffin-v-illinois/?q=cites%3A(91704)

- Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, Court Listener, last accessed:645pm,7/22/2022, https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/106997/swain-v-alabama/?q=cites%3A%2891704%29&page=2

- Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202(1982), JUSTIA, US Supreme Court, last accessed:4:48pm, 7/22/2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/457/202/#tab-opinion-1954578