Author: Rosie Pingxin Zhou

Introduction

In May 2021, following the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes occurring around the country, I felt a sense of urgency to talk about Asian American history and the importance of teaching it. I recognized that the rise in anti-Asian hate was part of a larger, historical trend of racially motivated violence against Asians in America. Quickly, I emailed my U.S. history teacher, who had taught me the year before, and he kindly offered me an opportunity to speak to his classes.

I began by giving a brief overview of Asian American history, and then dived deeper into the case of Vincent Chin. When I asked who had heard of the name Vincent Chin, not a single person responded. I was shocked and saddened that no one knew the story of Vincent, who had been killed with a baseball bat because of the color of his skin, only to have his death erased from history textbooks and unknown by future generations.

Vincent’s story is important to learn, not only because racial violence against Asians continues to this day and we have yet to fully learn from our history, but also because the protests invoked by Vincent’s death revealed the power of pan-Asian unity, collective action, and community mobilization.

Who Was Vincent?

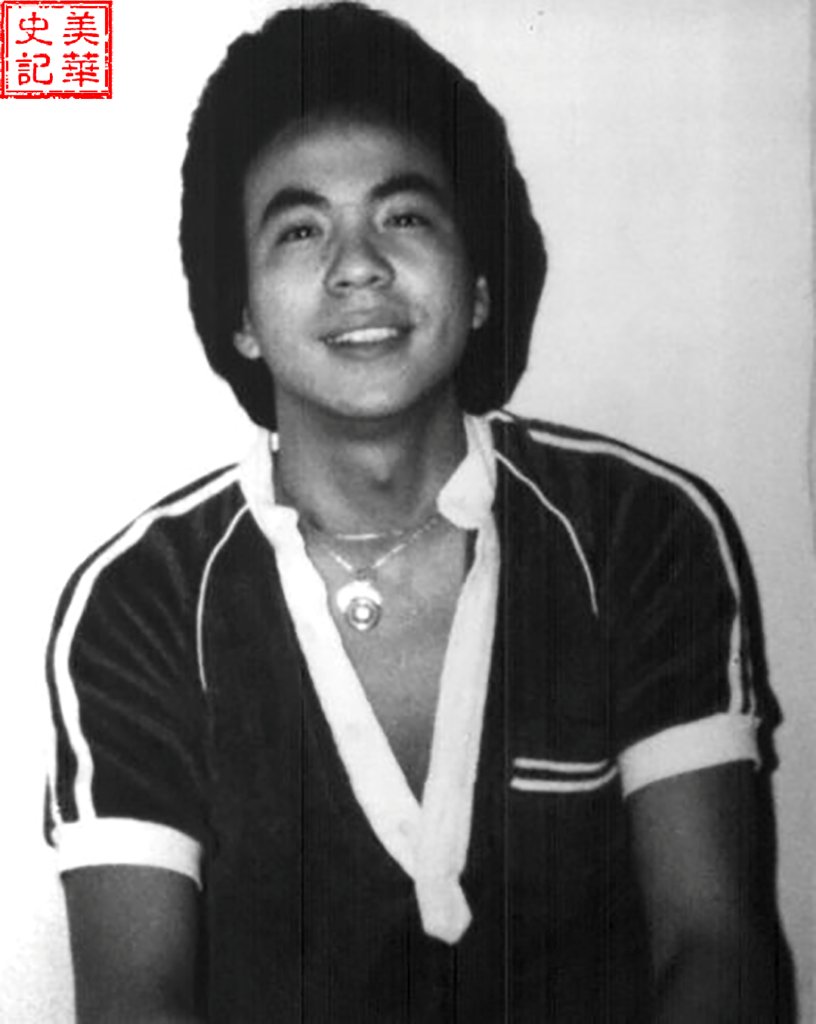

Vincent was adopted from China at the age of six by David Chin and Lily Chin.[1] As his childhood friend Gary Koivu describes in the documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin, Vincent adjusted quickly to the new country and American school environment.[2] In Gary’s words, “I think Vincent fit in very well. He learned the ways of America and he didn’t seem to be handicapped by the fact that he was Chinese, he had a lot of friends and a lot of girl friends. People accepted him pretty rightly. He had a very good sense of humor, he was always laughing.”

Photo 1: Photo of Vincent Chin. Courtesy of American Citizens of Justice.

Source:https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/who-vincent-chin-history-relevance-1982-killing-n771291

Vincent’s parents, David and Lily Chin, worked in the few industries where Asian immigrants could find jobs – laundries and restaurants.[3] Upon graduating, Vincent worked as a draftsman during the day and waiter on weekends, helping to support his family financially. Vincent looked forward to getting married, finding a good engineering job, and someday having children. In 1981, Vincent’s father died and Lily was left a widow. She planned to move in with Vincent and his wife, as that was the traditional thing to do in Chinese families.

As journalist, activist, and key figure in the Vincent Chin case, Helen Zia, describes in her book, Vincent knew little of the history of racial violence against Asians in America.[4] But he had witnessed the hardships of his immigrant parents, who had endured racism upon coming to America. As Lily Chin recounts in the documentary, “When the neighborhood kids saw us in the basement they made ugly faces. They stuck out their tongues and made as if to slit our throats.”[5] She describes a separate instance, “When I first came here I didn’t know much of anything! So my husband liked to take me to new places. We went to see a baseball game. But when people saw Chinese sitting there they kicked us and cursed at us. I never went back.” Negative sentiments towards Asians were clearly prevalent and would only increase as the general public became increasingly frustrated by a rise in Japanese automobile imports and a fall in the American auto industry.

Setting the Scene – A Collapsing Industry, Rising Frustrations, and Japan-Bashing

In 1978, a new oil crisis and subsequent gas price increases led to the heavy gas-guzzlers made in Detroit to become much lower in demand.[6] Japanese auto imports were, on the other hand, cheap to buy, cheap to run, and dependable. Leading up to the summer of 1982, the automobile industry in Detroit started to collapse, and Detroit began to experience an economic crisis. Unemployment rates rose, along with workers’ frustrations. At first, workers were blamed. But before long, workers and companies found a common enemy to blame – the Japanese.

Anything Japanese, or presumed to be Japanese, was increasingly targeted. Union-sponsored bashings of Japanese cars using sledgehammers became commonplace. Anti-Japanese rhetoric spread like wildfire and was reinforced through the media. Politicians and public figures exacerbated the scapegoating of the Japanese, publicly making irresponsible remarks aimed at Japanese people. As Helen Zia, who had been working in the industry herself, remarked, “It felt dangerous to have an Asian face. Asian American employees of auto companies were warned not to go onto the factory floor because angry workers might hurt them if they were thought to be Japanese.”[7] As reporter Shelley Czeizler observed, many politicians’ “verbal bullets aimed at the Japanese government and carmakers have strayed off course and are hitting home instead.”[8] It was in this context that Vincent Chin was wrongfully deemed Japanese and targeted by Ronald Ebens.

The Night of the Beating

On June 19, 1982, a week before his wedding, Vincent went out to a bachelor party with his friends.[9] They went to a striptease bar in Highland Park called Fancy Pants. At the lounge, Ronald Ebens, a plant superintendent for Chrysler, and his stepson, Michael Nitz, a laid off autoworker, disliked Vincent’s presence and soon provoked him with the sentence, “It’s because of you motherf****** that we’re out of work.” A fight ensued and the two were soon kicked out of the bar.

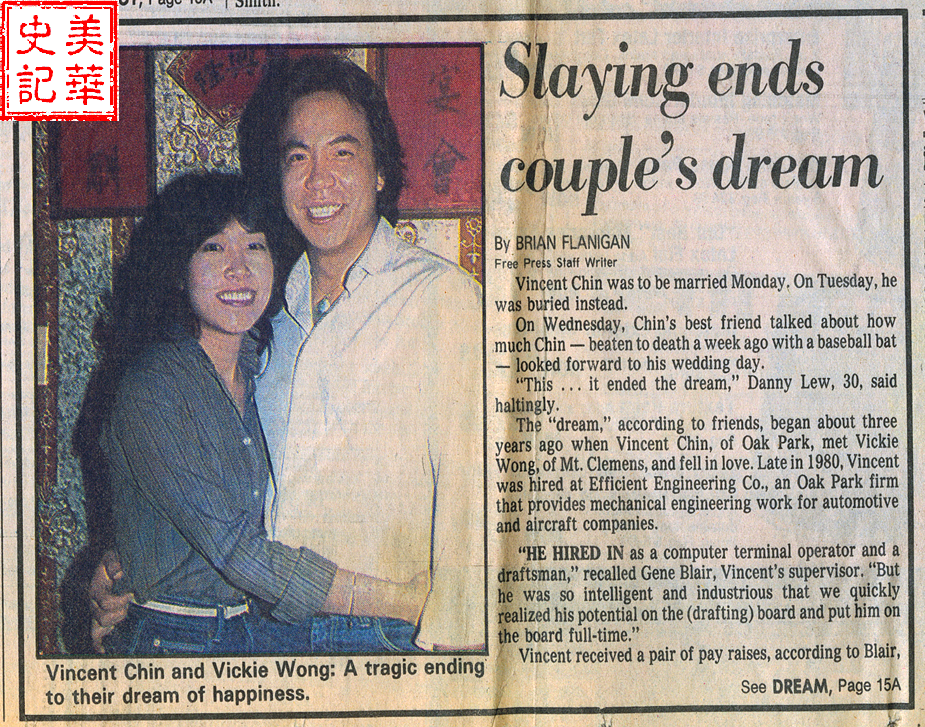

Chin and his friends drove away trying to escape, but Ebens and Nitz were determined to find Chin and the other Chinese man in his group. They hired a man to drive them through the neighborhood and help them “get the Chinese.”[10] They eventually spotted Vincent and his friend in front of a McDonald’s on Woodward Avenue. Ebens crept up behind Vincent, his Louisville Slugger baseball bat in hand. Nitz held Vincent down while his stepfather swung his bat into Vincent’s skull four times, “as if he was going for a home run.”[11] Two off-duty cops witnessed the attack. Mortally wounded, Vincent died four days later in the hospital. While his friends and relatives should have been attending his wedding, they attended his funeral instead. In the documentary, Lily Chin recounts the painful experience of seeing her son lying unconscious on the hospital bed, “I kept on crying and crying. Vicki was holding me. I said over and over Vincent, Mama come. You answer me, open your mouth Move your mouth. Let mama see you. But no feeling. I touched him many times.”[12]

The Outrageous Ruling and Subsequent Organizing for Justice

Photo 2: “Slaying ends couple’s dream,” by Brian Flanigan. An article clipping from the Detriot Free Press, Thursday, July 1, 1982. Courtesy of Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” Collection.

Source:https://www.mocanyc.org/2022/06/21/vincent-chin-40th-year-remembrance-june-19-23-1982/

The Detroit Free Press featured the incident on its front page, describing Vincent’s life, but offering no details because the circumstances were still unknown.[13] Detroit’s Asian Americans quickly took notice, and even though many could sense that race was a factor in the killing, they remained silent. The community was not yet organized and galvanized to take action.

The tides began to turn, however, nine months later. On March 18, 1983, new headlines appeared in the papers, “Two Men Charged in ‘82 Slaying Get Probation” and “Probation in Slaying Riles Chinese.” The two killers pleaded guilty, and each only received three years’ probation and $3,780 in fines and court costs to be paid over three years.[14] The judge, Charles Kaufman, explained his reasoning: “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail. You fit the punishment to the criminal, not the crime.” The lightness of the sentence immediately sparked outrage among people in Detroit. Detroit Free Press columnist Nikki McWhirter wrote, “You have raised the ugly ghost of racism, suggesting in your explanation that the lives of the killers are of great continuing value to society, implying they are of greater value than the life of the slain victim…How gross and ostentatious of you; how callous and yes, unjust…”

The Chinese American community was especially outraged. Many shared the same immigrant, working class background as the Chin family and the injustice surrounding Vincent’s death shattered the American dream that they had so desperately strived to obtain. Detroit News reporter Cynthia Lee interviewed members of the community, who voiced their disbelief.[15] Henry Yee, a local restaurateur who was well known among the community, pointed out the injustice of the case, saying, “You go to jail for killing a dog.” A distraught family friend cried that Vincent’s life was worth less than a used car.

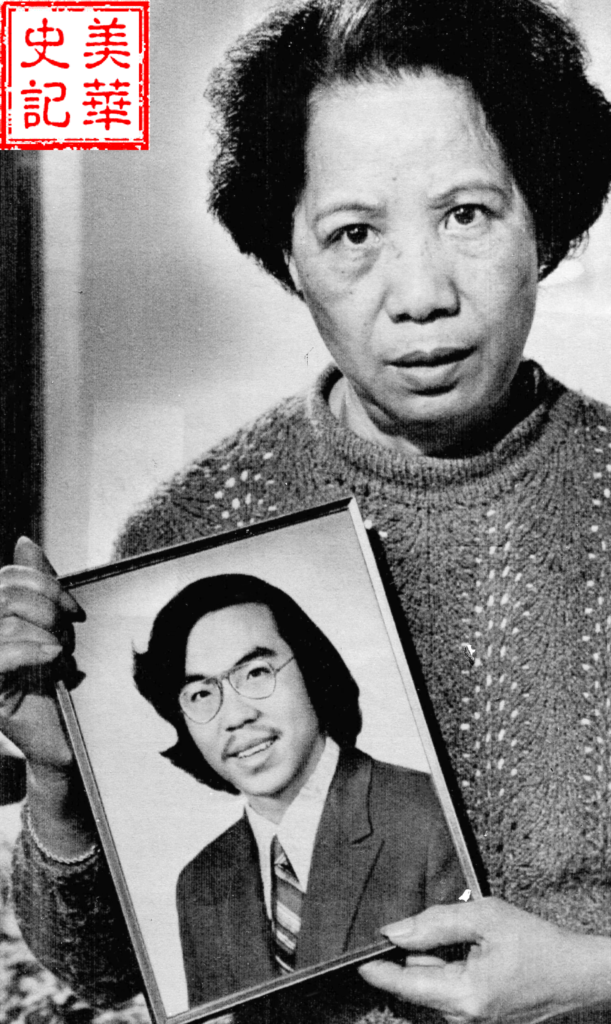

Lily Chin was devastated by the news. She wrote a letter in Chinese to the Detroit Chinese Welfare Council, “This is injustice to the grossest extreme. I grieve in my heart and shed tears in blood. My son cannot be brought back to life, but he was a member of your council. Therefore, I plead to you. Please let the Chinese American community know, so they can help me hire legal counsel to appeal, so my son can rest his soul.”[16] Motivated by Lily’s letter, Henry Yee and Kin Yee called for a meeting one week after the sentencing at the Golden Star Restaurant, where Vincent used to work as a waiter. About thirty people attended. The half dozen of lawyers in attendance constituted the majority of Asian American attorneys in the entire state. They agreed that little could be done to change a sentence once it had been rendered and that the law offered few options. An uneasy quiet covered the room, the only sounds being Lily Chin’s weeping in the back of the room.

Photo 3: Lily Chin holds a photograph of her son Vincent in November 1983.

Source: https://www.vox.com/2022/6/19/23172702/vincent-chin-murder-fortieth-anniversary

Photo 4: Helen Zia comforts Lily Chin as Chin starts to cry during a press conference in Ferndale following the verdicts in the Ebens/Nitz trial. Pauline Lubens, Detroit Free Press.

At that moment, Helen thought to herself that she had to decide between being a reporter on the sidelines and being an active participant in whatever happened. She hesitated, then raised her hand and said, “We must let the world know that we think this is wrong. We can’t stop now without even trying.”[17] At first there was no response. Then the weeping stopped. Mrs. Chin stood up and spoke in a shaky but clear voice. “We must speak up. These men killed my son like an animal. But they go free. This is wrong. We must tell the people, this is wrong.”

Catalyzing off of these sentiments, the group decided to press forward. The lawyers recommended a meeting with the sentencing judge, Charles Kaufman. Liza Chan, the only Asian American woman practicing law in Michigan, volunteered to accompany Mrs. Chin and Kin Yee to meet the judge. Helen Zia took on the task of publicizing the news that Asian Americans were outraged and preparing to fight the judge’s sentence. From the beginning, women would play a major role in the case.

Judge Kaufman, flooded by angry phone calls, letters, and media inquiries, avoided meeting with them. Liza began to find and interview witnesses to reconstruct what happened to Vincent Chin that fateful night, so that Mrs. Chin and the community could assess their legal options. It soon became clear that there were failures at every step of the criminal justice process, from the police and court record to the failure to interview numerous witnesses.

After the community meeting at the Golden Star, Helen Zia issued their first press release.[18] They received numerous responses and offers to help, to which they decided to hold a meeting to discuss next steps moving forward. Their first meeting, held at the Detroit Welfare Council building, included more than a hundred middle-aged and mainly middle-class Asian Americans from towns surrounding Detroit. The majority in attendance were Chinese Americans, but non-Chinese were also represented, including the Japanese American Citizens League, the Korean Society of Greater Detroit, and the Filipino American Community Council. They discussed the formation of a pan-Asian organization that might seek a federal civil rights investigation in the muder of Vincent Chin. There had never before been a criminal civil rights case involving anyone of Asian descent in the United States.

The pan-Asian intent of the group became clear as they discussed what to name the new organization and agreed upon “American Citizens for Justice.”[19] The founding of ACJ marked the formation of the first explicitly Asian American grassroots community advocacy effort with a national scope. A distinct pan-Asian identity was beginning to form. Japanese, Filipino, and Korean American groups joined in support, and both white and Black individuals also volunteered, making the campaign for justice multiracial in character. That night, ACJ drafted its statement of principles:

- All citizens are guaranteed the right to equal treatment by our judicial and governmental system;

- When the rights of one individual are violated, all of society suffers;

- Asian Americans, along with many other groups of people, have historically been given less than equal treatment by the American judicial and governmental system. Only through cooperative efforts with all people will society progress and be a better place for all citizens.

ACJ quickly gained the attention of local media; never before had Asian Americans come together to protest injustice. With the growing prominence of the case, Asian Americans were propelled into the given white-black race dynamic with an Asian American issue. As Helen Zia explains, “We tried to explain that we recognized and respected African Americans’ central and dominant position in the civil rights struggle; we wanted to show that we weren’t trying to benefit from their sacrifices without offering anything in return. On the other hand, many European Americans were hostile or resistant to ‘yet another minority group’ stepping forward to make claims. Underlying both concerns was the suggestion, a nagging doubt, that Asian Americans had no legitimate place in discussions of racism because we hadn’t really suffered any.”[20]

Many members of the African American community in Detroit were supportive of the growing Asian American movement. The umbrella Detroit-Area Black Organizations quickly endorsed ACJ’s efforts, and the Detroit chapter of the NAACP, the largest chapter in the country, issued a statement about the sentence. Several prominent African American churches gave their support. Other communities too, including Latinos, Arab Americans and Italian Americans, supported as well. Some women’s groups such as the Detroit Women’s Forum and Black Women for a Better Society endorsed ACJ, as well as a number of local political leaders.

At first, ACJ was tentative to tie the murder with race, as the evidence provided was not yet sufficient to support claims of race being a factor. This changed when a private investigator hired by ACJ reported that Racine Colwell, a blond dancer at the Fancypants, overheard Ebens tell Chin: “It’s because of you motherf****** that we’re out of work.”[21] Given the backdrop of anti-Japanese rhetoric being so commonplace, Asian Americans knew what Ebens meant. ACJ attorneys and leaders recognized it was enough to charge Ebens and Nitz with violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights.

At the next ACJ meeting, more than 200 people attended. A speaker from the US Department of Justice explained the difficult process of getting the federal government to conduct a civil rights investigation. The FBI would need to show that there was a conspiracy to deprive Vincent of his civil rights. A gray-haired engineer from General Motors spoke up, “If we try to pursue a civil rights case, is it necessary to talk about race?”[22] He voiced the conundrum of the crowd – where did Asian Americans fit in America? Asian Americans had never before been involved in conversations about race – nor had they injected themselves. Organizing over race might lead them to be perceived negatively by the white establishment.

As attendees of the meeting pondered upon this conundrum, they also shared frustrating personal experiences that had brought them to the meeting – why the Vincent Chin case had touched and outraged them. One computer programmer said, “They always pass me over for promotion because I’m Chinese. I have trained many young white boys fresh out of college to be my boss. I never complain, but inside I’m burning. This time, with this killing, I must complain. What is the point of silence if our children can be killed and treated like this? I wish I’d stood up sooner and complained a lot sooner in my life.”[23]

As Helen Zia recounts, the group had reached a consensus by the end of the meeting: “To fight for what we believed in, we would have to enter the arena of civil rights and politics. Welcome or not – Asian Americans would put ourselves into the white-black race paradigm.” With this newly developed purpose, ACJ began to publicize its findings of racial slurs and comments made by Vincent’s killers and to call for a civil rights investigation. Unsurprisingly, they immediately faced backlash, prominently from white liberals like Wayne State University constitutional law professor Robert A. Sedler, who believed that civil rights were enacted to protect only African Americans, not Asian Americans – who were considered white. The Michigan ACLU was not interested in the civil rights aspect of the Vincent Chin case.

In spite of backlash, local, national, and international support for ACJ’s efforts was growing daily.[24] This marked the first time that an Asian American initiated issue was considered national news. With this historic momentum, ACJ decided to hold a citywide demonstration at Kennedy Square in downtown Detroit, where many historic protests had occurred. The protest invoked an unprecedented outpouring of support – hundreds of Filipinos, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans from all different professional backgrounds marched together in pan-Asian unity. This protest marked a transformative moment within Asian American history. Interviews from Who Killed Vincent Chin demonstrate how important this protest was towards people. As an elderly woman said, “From the very beginning of our background, our parents have always taught us to be very low-key and not to participate in activities or… or even in… in politics. So the Asian-Americans have been always in the background and reluctant to speak out.” Another woman said, “To change the image of Asian people, our image of passiveness, able to sit, just doing nothing, just accept whatever is coming to us, we decided it’s time to stand up for our rights.”

Photo 5: Asian Americans For Equality participating in a protest for Vincent’s justice (photo taken by Corky Lee).

Source: https://www.aafe.org/who-we-are/our-history/aafe-vincent-chin-protestcorky-lee

Supported by Helen Zia, Lily Chin began to speak at community gatherings, protests and rallies, demanding justice for her son and gaining support and solidarity from Black leaders like Jesse Jackson. Her remarkable courage and resilience inspired Asian Americans across the country to join the movement. Her powerful words struck the nation at the end of the rally in Detroit, “I want justice for my son. Please help me so no other mother must do this.”[25]

Photo 6: Lily Chin speaks at a news conference in 1983 at historic Cameron House in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Rev. Jesse Jackson took time from his presidential bid to show support for the national campaign to seek Justice for Vincent Chin. Pictured on stage, left to right: Henry Der, Edward Lee, Rev. Jackson, Lily Chin, Butch Wing, Helen Zia, Mabel Teng, Alan Yee.

Source: https://www.aasc.ucla.edu/resources/untoldstories/UCRS_Vincent_Chin.pdf

Through demonstrations around the country, ACJ launched its call for a federal prosecution of the killers for violating Chin’s civil right to be in a public place. Highlighting the broader context, ACJ emphasized how prevalent anti-Asian violence had become because of the scapegoating of Asian Americans. Pan-Asian coalitions formed across the country, supporting ACJ’s mission and organizing to address anti-Asian violence in local communities. Unity was difficult to maintain among these coalitions due to conflicts arising over “homeland politics,” but a common purpose and collective vision brought people together and allowed them to transcend ethnic and cultural boundaries.[26]

In November 1983, a federal grand jury indicted Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz for violating Vincent Chin’s right to enjoy a place of public accommodation.[27] The trial would take place the following June. During this period, other racial attacks against Asian Americans occurred.[28] In Lansing, Michigan, a Vietnamese American man and his European wife were harassed and repeatedly shot at by white men shouting racial slurs. In Davis, California, a seventeen-year-old Vietnamese youth was stabbed to death in his high school by white students, while in New York a pregnant Chinese woman was decapitated when she was pushed in front of an oncoming subway car by a European American teacher who claimed to have a fear of Asians. Evidently, Vincent’s death was only a part of a larger trend of violence against Asians.

Miscarrying of Justice

On June 28, 1984, the federal jury found Ebens guilty of violating Vincent Chin’s civil rights and Judge Taylor sentenced Ebens to 25 years.[29] Nitz was acquitted. But the case didn’t end there – it won a retrial on appeal in 1986, and the new trial would be held in Cincinnati. This location of the new trial was certainly strategic, as very few Asians lived in Cincinnati, and the jury that was eventually seated was mostly white, male, and blue-collar. The jury of this second civil rights trial reached its not-guilty verdict on May 1, 1987, nearly 5 years after Vincent Chin was killed.[30] Though disappointing, the verdict was not surprising given how little understanding the jury had of Asian Americans, as well as the racial undertones behind Ebens’s and Nitz’s actions.

Lily Chin was, once again, devastated by this verdict. “Vincent’s soul will never rest,” she said, “My life is over.” Every day she grieved for Vincent. She moved to New York, then San Francisco, to stay with relatives, and finally to her birthplace in Guangdong Province, China, after spending 50/70 years in the U.S. She never got to see justice brought to her dear only son.

Though a civil suit was filed against Ebens and Nitz for the loss of Vincent’s life in 1987 and Ebens was ordered to pay $1.5 million to the Chin family, he stopped making payments towards the judgment in 1989. Ebens never publicly expressed remorse for taking Chin’s life, nor did he ever spend a full day in jail.[31]

The Legacy of the Vincent Chin Case

ACJ vowed to continue its mission of equal justice for all. Though they had ultimately lost this legal battle after five years of organizing, the Asian American community had been transformed. Since then, the legacy of the Vincent Chin case has lived on. Through documentaries like Who Killed Vincent Chin by Renee Tajima-Peña and Christine Choy and Vincent Who by Curtis Choy, organizations such as the National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium being founded, and growing political awareness about anti-Asian racism, Vincent’s story and the lessons behind it have influenced countless people and remain important to this day. As Yen Le Espiritu, professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California at San Diego, wrote in her book Asian American Panethnicity, “As a result of the Chin case, Asian Americans today are much more willing to speak out on the issue of anti-Asianism; they are also much better organized than they were at the time of Chin’s death…Besides combating anti-Asian violence, these pan-Asian organizations provide a social setting for building pan-Asian unity.”[32]

As we continue to see anti-Asian racism prevalent in our world today, it is critical to teach about Vincent Chin’s case and its legacy. It is my hope that more young people can learn the name “Vincent Chin” and understand the importance of his story. Students should learn about Vincent Chin’s case in American history class, along with other critical moments in history relating to the Asian American experience. Even more, the pan-Asian, multicultural organizing for Vincent’s justice can serve as inspiration for today, as we continue to face issues relating to scapegoating and racially motivated violence.

Conclusion

The murder of Vincent Chin in 1982 and the subsequent protests for Vincent’s justice marked a turning point in the history of Asian America. Vincent’s murder was not just the result of a drunken brawl gone wrong, of something that, as Ronald Ebens claimed “just happened,” it was a culmination of Ebens viewing all Asians as the same and his resentment towards the Japanese, falsely accusing them of “stealing” U.S. jobs.

Although Nitz and Ebens were both ultimately acquitted and Vincent was never brought true justice, the movement that developed from the case was a monumental moment in Asian American history. By standing up together to demand for an end to racially motivated violence and for the legal system to recognize the killing as a hate crime, Asian Americans brought the Vincent Chin case to the forefront of American society. They demonstrated the power of coming together behind a common purpose and mobilizing against injustice.

The last scene of Who Killed Vincent Chin features Lily Chin speaking to us, the viewers. “ Please, all of you good and honest people,” she says shakingly, “Please, I want everybody, tell the government do not drop this case. I want justice for Vincent. I want justice for my son. Thank you for all.” Lily Chin’s pleas reverberate to this day, calling on us to honor Vincent by speaking out, demanding justice, and educating people about his story.

References

Choy, Christine and Tajima-Peña, Renee. Who Killed Vincent Chin. Film News Now Foundation and WTVS, 1987. 87 min.

“Who is Vincent Chin?” Vincent Chin 40th Remembrance & Rededication. https://www.vincentchin.org/

Woo, Elaine. “Lily Chin, 82; Son’s Killing Led to Rights Drive.” Los Angeles Times, 2002. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-jun-14-me-chin14-story.html#:~:text=Lily%20Chin%2C%20whose%20grief%20and,She%20was%2082.

Zia, Helen. Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People, 70-93. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1st edition, 2001.

[1] Woo, Elaine. “Lily Chin, 82; Son’s Killing Led to Rights Drive.” Los Angeles Times, 2002.

[2] Choy, Christine and Tajima-Peña, Renee. Who Killed Vincent Chin. Film News Now Foundation and WTVS, 1987. 87 min.

[3] Who is Vincent Chin? Vincent Chin 40th Remembrance & Rededication.

[4] Zia, Helen. Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People, 70. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1st edition, 2001.

[5] Supra note 2.

[6] Supra note 5, at 69.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Supra note 2.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Supra note 5, at 70.

[11] Supra note 2.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Supra note 5, at 71.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Supra note 5, at 72.

[16] Ibid, at 75.

[17] Ibid, at 76.

[18] Ibid, at 77.

[19] Ibid, at 78.

[20] Ibid, at 80.

[21] Ibid, at 81.

[22] Ibid, at 82.

[23] Ibid, at 83.

[24] Ibid, at 84.

[25] Ibid, at 86.

[26] Ibid, at 87.

[27] Ibid, at 88.

[28] Ibid, at 89.

[29] Ibid, at 90.

[30] Ibid, at 91.

[31] Ibid, at 92.

[32] Ibid, at 93.