Author: Xin Su

Translator: Audrey M. Jiang

ABSTRACT

The Mississippi Delta, for a long time, has been a multiracial land where both black and white people lived. However, this is not to say that different races have never inhabited this area. They have, and one group, the Delta Chinese, made quite an impression. For one, they challenged the long-standing social order when they arrived. Secondly, they originally came to pick cotton, but made a drastic change to opening stores when working in the fields did not prove lucrative. These stores, often located in African American communities, did much to shape the local economy. Their success story is made even more impressive when you consider the social and political climate of the time– the Chinese Exclusion Act, spurred on by overwhelming anti-Chinese sentiment, had been passed not long before. In a way, their story embodies the quintessential American Dream or immigrant story– they were a group of people who had to fight for the opportunity for better lives and also made contributions to the country.

Introduction

A portion of Chinese Americans migrated south to an alien, unfamiliar land where white people and African Americans lived largely segregated– the Mississippi Delta. There they relied on opening small grocery stores for money, carved a unique position in society, and rose above their struggles.

The ability to withstand a harsh political and economic environment and yet stubbornly live on should be considered a miracle.

What power was it that allowed them to conquer poverty and proudly multiply in number?

What kind of wisdom was it that allowed them to persevere in the fiercely competitive environment and come out stronger?

What kind of hard work allowed them to win educational resources, to raise many shining examples of talent?

What patriotic sentiment was it that drove them to accept their duty, making sacrifices for their country, on the path to ultimate glory?

Let us walk down once again the difficult and glorious path traveled by our ancestors.

Figure 1, a timeline of the southern migration of the Delta Chinese

Chinese Americans Migrate to the Mississippi Delta

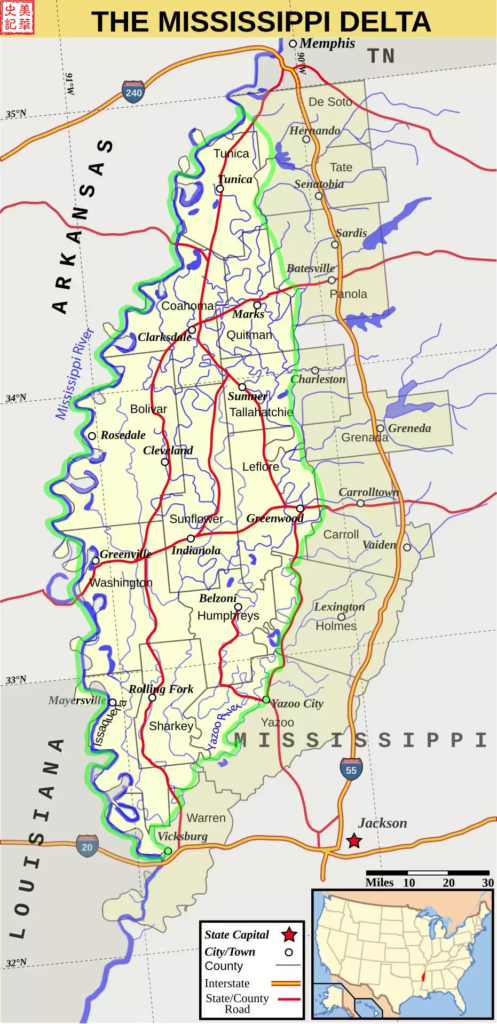

The Mississippi Delta is located in the northwestern part of Mississippi, between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. Due to its unique ethnic, cultural, and economic history, this area has been called “the most southern place on Earth” [1]. 200 miles long and 87 miles at its widest, it contains about 4,415,000 acres of alluvial floodplains.

Figure 2, location of the Mississippi Delta. Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mississippi_Delta [2].

In the beginning the region was covered in hardwood forests. Before the American Civil War (1861-1865), it was one of the richest cotton-growing areas in the whole country. The cotton that was cultivated along the banks of the river attracted many speculators to the area, who would become plantation owners dependent on slaves for their wealth. Because of this, African American slaves outnumbered white people two to one before the Civil War [2]. After the war, during the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) – which coincided with the end of slavery and the defeat of the Confederacy, Mississippi was thrown into a significant period of turmoil. The relationship between free African Americans and white people was extremely strained.

The first wave of Chinese immigration to the Mississippi Delta began after the Civil War – in that time, the labor system was unstable and plantation owners were in urgent need of cheap labor, and so hired many Chinese workers to replace the freed African American slaves. Because of their political silence, hard work, and, as mentioned before, a great source of cheap labor, Chinese workers became the best choice [3].

Apart from taking up jobs as laborers, Chinese workers were also pushed south by powerful anti-Chinese sentiment in the northwest. Calls for Chinese exclusion began as early as 1862, afterwards they began calling on Congress to slow down or stop the flow of Chinese immigration. Finally, in April 1882, the Senate passed the Chinese Exclusion Act (32 Yea, 15 Nay, 29 Not Voting), as did the House (202 Yea, 37 Nay, 52 Not Voting). On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law [5]. The passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act caused considerable harm to the lives of Chinese Americans; in the northwest, massacres, riots, and robberies toward Chinese Americans occurred one after the other. The number of Chinese Americans migrating south increased.

Why did Chinese Americans go south to the Mississippi Delta? It was because the climate of the Delta was quite similar to that of their home, the Siyi (Sze Yup) region of Guangdong [3]. The social structure depended on race and class. Everybody knew their place in the social hierarchy without being told. Just when whites and African Americans were carrying on in their established social order, a few Chinese Americans decided to put down their roots in the Delta and find their own footing.

Initially, Chinese Americans mainly worked in the cotton fields. Some came from California, others were coolies freed from sugarcane fields, and still others were local railroad workers [6]. A year later, however, employers discovered that the plan of using Chinese workers to cover for freed slaves was a bad idea, as Chinese workers were not used to working in the fields. On the other hand, Chinese workers also quickly realized that plantation work was unable to earn them economic success. In the fields by sunrise, done by nightfall, face to the ground and backs to the sky. Employers often owed workers wages as well, which caused no small amount of dissatisfaction. Eventually, Chinese workers were no longer willing to work in the cotton fields. But in such a remote place, whose economy was dominated by field labor, it was not easy to open a laundry shop [6].

Though many of these Chinese immigrants came from farmer or artisan families, their home region of Siyi, Guangdong was a relatively commercialized area, with a focus on business and trade [4]. They were more suited to selling sundry goods or opening grocery stores, so some of the pioneers of Chinese southern migration began making the switch from working on plantations to business. Chinese Americans shaped the local economy by opening grocery stores [7]. By the time of the 1920 census, store owner was the only occupation of Chinese Americans [6].

Many Chinese immigrants of the time were looking to make money rather than societal acceptance [4].

Successful Family Business Model

The first Chinese grocery store in Mississippi may have appeared in the early 1870s– tax records from early 1880 show that Chinese Americans were already owning land in Rosedale in Bolivar County by then [4].

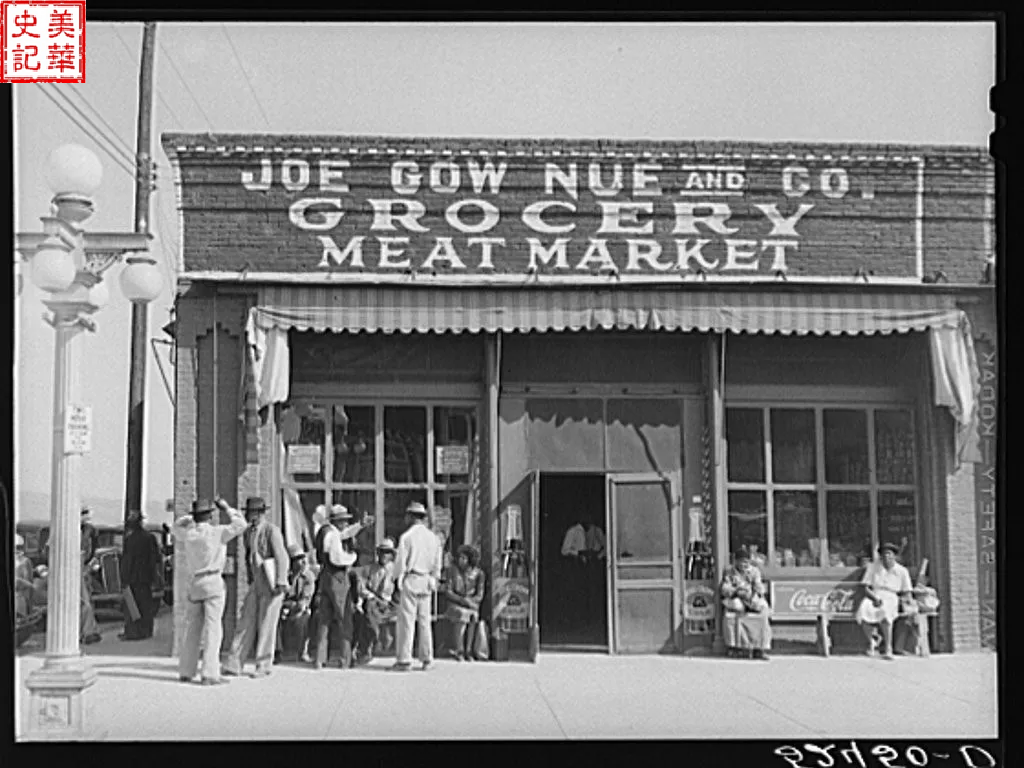

During this period, the first stores of many grocery store owners was a small house stocked with a small amount of goods, like meat, corn starch, or molasses. In addition, these stores also supplied fresh vegetables, canned food, detergent, soap, and other daily necessities. Aside from store owners, there were not many Chinese Americans in the area [4]. Chinese grocery stores were generally located in African American districts, with the whole family living in the backyard of the store. By 1920 many store owners had opened restaurants in the backyard of their stores [6].

Chinese shops were mostly oriented toward low-income plantation workers, or other laborers, like swamp drainers, loggers, or urban manual laborers [4].

In the years immediately following the Civil War, migrants to Mississippi could buy land in exchange for clearing the land and selling the lumber. Before the end of the nineteenth century, African Americans occupied a hefty two-thirds of the land area. However, after 1890, state legislatures found a way using legal means to restrict the rights of African Americans. Eventually they lost their land due to a credit crunch and political oppression and became poorer and poorer [2].

At that time segregation was a very serious phenomenon and white vegetable shops could only serve white people. Seeing an opportunity, Chinese business owners grabbed it, opening low-priced vegetable shops in African American residential areas [3].

In those days, stores were not self-service: customers would tell workers what they wanted to buy. Chinese store owners initially did not speak English, and customers did not understand Chinese, resulting in them using hand gestures to complete transactions. Buying a bag of corn starch was a complicated matter. Because of the language barrier, Chinese Americans were often exploited [4].

One of the reasons why Chinese grocery stores were able to overcome hardships was the model of family businesses.

Traditionally, young Chinese men would first come to America to earn some money to support their families. When they had accumulated enough financial resources, they would then bring their other family members over to the area [4].

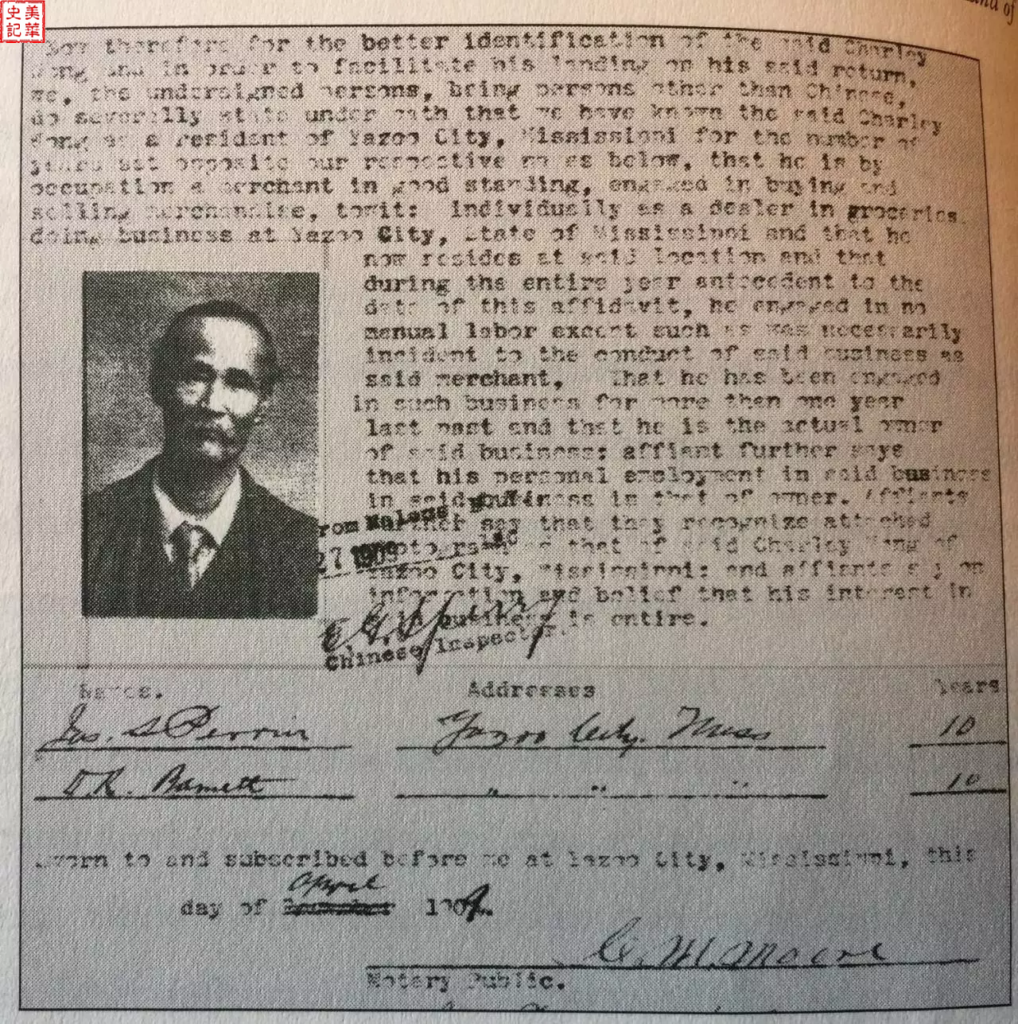

After the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese workers were not permitted to enter the US, but if a businessman was able to prove that someone was a relative of theirs, they could then bring that person to the US and that person would be able to move the Mississippi Delta [6, 7].

Figure 3, Charlie’s 1909 return documents after he traveled overseas to visit his family in China. He needed two white witnesses to prove that he had a business in the Mississippi Delta and had never done labor before. Source: Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton, Lives of Mississippi Delta Chinese Grocers [6].

The first small-scale shops were managed by a single family. Bonds between members were built on the basis of mutual trust. They could sacrifice their personal freedom for working longer hours. Every member was loyal and dedicated regardless of personal gains and losses, and everyone did all that they could to work.

Family members learned about business operation from their work. At this time, relatives would accumulated some savings and borrow some money to help other family members open shops independently. Wholesale suppliers, because of the integrity of Chinese shop owners, were more willing to lend money. Due to hard work, accumulation of business experience, and good reputations, Chinese stores became more and more prosperous.

Figure 4, grocery store circa 1930-1940. Source: Marion Post Wolcott/Library of Congress

More often than not, grocery stores passed from fathers to their sons or other family members. By the end of 1970s, 80% of the Delta Chinese consisted of six family names [4].

Unity, cooperation, and shared development was another reason why Chinese stores were successful. Though there was economic competition between different vegetable shops, cooperation between them was generally good. By sharing the responsibility of restocking goods, they managed to keep prices low and maintain their advantage.

The Chinese, when doing business, were always honest, with their service attentive. African Americans of the time were often poor to the point of not being able to buy food, and so Chinese store owners allowed them to buy on credit. These debts were due when wages were paid. In this way, Chinese store owners won the trust of many African Americans [6]. If you think about it, trust is a very good way of showing respect to the customer. This system brought a lot of business around to the shops, allowing them long-term survival and development.

Chinese Americans used all the resources they could and did their utmost to survive. They did not escape the harsh conditions of the time, but they did proactively make the most out of the reality of that society. They bravely swam against the current, and continued to persevere.

Surviving in a Unique Environment Where Three Races Must Coexist

Chinese immigrants added a third element to the original white-and-African American social order, bringing with opportunities and extra competition. Though there were many African Americans in the Delta, and they were also the source of most Chinese business, they were low on the rungs of the social ladder and were oppressed by white people, who wielded absolute power. In a severely segregated society, the Chinese served as a sort of bridge between white and African Americans [4, 6].

Despite the fact that Chinese Americans were culturally and linguistically different from the African American so the Delta, the local white people saw them much the same: second-class citizens of low status, the only difference being that their skin was lighter. Economically, though, Chinese Americans managed to escape the cotton fields and found different business opportunities, which meant that they were economically better off than the average African American.

Chinese Americans’ dedication earned them economic success, they still maintained some amount of distance from the rest of society– they did not attend clubs, fraternities, or entertainment activities [4].

Chinese Americans were not always the most conscious of race. Most of their customers were poor African Americans, and they lived in African American neighborhoods. These customers were willing to sit down in Chinese shops and talk, and sometimes even found temporary work there.

When the economy was in recession, the first to be fired were African Americans– and when African Americans did not have money, Chinese American shops would also feel the strain too. It was the same with the lows of the cotton industry.

Small grocery stores in impoverished areas were often the targets of robbery, as many people knew that Chinese American stores were likely to have money on hand, which they would then use to buy drugs. When shop owners got up to see what was happening, they often put their lives into danger as well.

Racial discrimination was present in a lot of Chinese American circles as well. Some Delta Chinese viewed themselves as more likely to receive white approval than African Americans, and treated African Americans much the same as white people treated them, often looking down on poorer Delta Chinese who ran with African American circles and those Delta Chinese who intermarried with them. John Jung [6] interviewed Robert Chow, a man who had lived there. He said: “Many Chinese Americans thought of African Americans as poor, cultureless, vulgar, and lazy.” This kind of racist thinking reflected back on daily life– the attitude of shop owners toward white and African American customers could not be more different– without fail, they were more friendly and more polite toward white people [6].

Chinese American Families and Education

Most Chinese immigrants were single when they first came to America, but there were also men who had to leave their wives in China. Of these Chinese immigrant men many had sexual relationships with African American women, but these relationships were secret and not to be spoken of. The society of the time was extremely unaccepting of interracial relationships, and mixed-race children were heavily discriminated against [6].

When economic conditions improved, more businessmen brought their wives and/or children over from China, so that they could finally enjoy family life. The number of Chinese women in the Delta increased after 1920, and the 1923 census showed that 11 Chinese children had been born there [6].

The Chinese Exclusion Act prompted the strange phenomenon of “paper sons” among Chinese Americans. The way it worked was that businessmen would offer a false certificate to immigration offices that proved that they had a son. The purpose of doing so was to create a quota for sons, that could be reserved to help skilled and unskilled laborers immigrate, send children to relatives, or to help a “paper son” immigrate. These “paper sons” were required to know the many, many details about their families and villages and the like to withstand the Immigration Bureau’s questioning [6].

In the beginning, many Chinese immigrants planned to make enough money and then return to their roots. With the passing of time, these Chinese immigrants realized that their dream of returning to their hometowns had shattered, and that they were fated to settle down in the United States and be buried there [6]. In towns like Greenville, Chinese Americans had their own cemeteries separate from white and black cemeteries. These cemeteries, however, were usually small but in a good location with a high wall surrounding them [4].

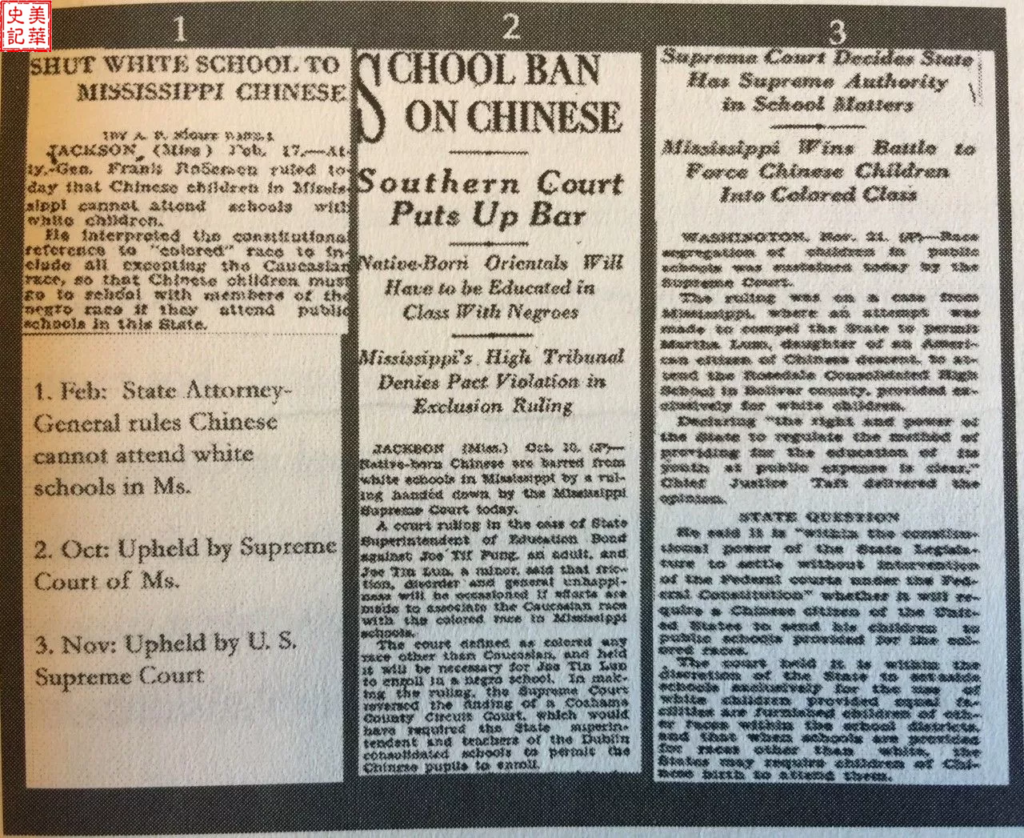

The Chinese have traditionally attached great importance to the education of the next generation. Public education was a big problem. At the time, black and white schools in the Delta were segregated. These schools were supposed to be “separate but equal,” but in reality, white schools had more educational resources than black ones. The Chinese were committed to working with white communities to make sure that Chinese children were receiving the same quality of education as their white peers. There were many challenges to that goal, among them the issue of the children of Chinese men and African American women who were excluded from white society. If white schools were to accept Chinese American children, what were to become of these mixed African-Asian children?

Chinese Americans also used legal means to try to solve the problem of educational discrimination. In the fall of 1924 Lum sued the Supreme Court of Mississippi (Gong Lum, et al v. Rice et.al, 275 US 78) because his daughter could not enter white schools. The lawsuit was dismissed in 1927, and the Court upheld the 1890 state constitution, ruling that the “yellow races” were colored people and therefore cannot enter white schools. The lawsuit was later re-tried by the Supreme Court, but it was sadly dismissed again. In the end, Lum and his family moved to Arkansas, where his daughter could attend a white school.

Figure 5, the Los Angeles Times and New York Times report on Mississippi’s Attorney-General ruling that Chinese children cannot attend white schools. This decision was backed by the Mississippi Supreme Court and the Supreme Court. Source: Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton, Lives of Mississippi Delta Chinese Grocers [6].

After the 1920s the situation underwent a change, the Delta Chinese formed civil society groups to try to unite Chinese Americans, create summer dance classes for high school and college students, and organized social clubs. Out of the desire to assimilate into white society, many Chinese Americans began attending white church activities.

In the 1930s, Baptists played a major role in the assimilation of the Delta Chinese into white society. Schools affiliated with the church began accepting Chinese students.

After World War II, with the improvement of US-Sino relations, Chinese children could finally enter some white schools. The admirable academic performance of Chinese children won many people’s respect. In the mid-1940s, some regions offered a small, separate class course for Chinese students. For example, in Cleveland Chinese students had two classrooms to themselves. There were 36 Chinese students total and three teachers, one of which was Chinese [4].

The issue of segregated schools was not completely resolved until 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education decided that any form of educational segregation was unconstitutional. Only then did schools experience the integration of multiple races.

According to statistics, the number of Delta Chinese who had received higher education (bachelor, master) from 1940 to 1950 was the highest in the United States [3].

Honor and Duty

Chinese Americans put their loyalty into practice through every part of their lives – their families, communities, and country.

Nobody knows exactly how many Chinese Americans enlisted in the army. According to rough estimates, about 12,000 to 20,000 Chinese men (about 22% of the men in their portion of the population) participated on behalf of the United States during World War II. Of those 12 to 20 thousand, about 40% were US citizens [8]. It is also said that from 1941-1945 about 13,000 to 16,000 first generation and/or second generation Chinese immigrants participated in the war. In the delta alone, records show that either 128 or 180 people enlisted in World War II. [3, 9] No matter which one is the true number, that was an astonishingly high portion of the population.

Figure 6, pictures of some of the Delta Chinese who joined the army during World War II. Source: http://www.openculture.com/2017/09/learn-the-untold-history-of-the-chinese-community-in-the-mississippi-delta.html [9].

American history remembers those Chinese Americans who fought for our country or committed themselves in service to it, and we salute them!

Diffusion of Chinese in Mississippi

World War II changed the way of life of the people of the Delta. Soldiers had the opportunity to live in other parts of America, and others on the European and Asian battlefronts got to see worlds that they’d never even dreamed of before. These experiences changed the way they viewed the world, improved their job opportunities and working skills, and influenced race relations and migration patterns. Many people left the Delta because of job opportunities.

Before the 1960s, Chinese Americans in Mississippi were concentrated in the Delta region. In 1960, the Chinese Americans in 14 Delta counties accounted for over 90% of the Chinese American population in Mississippi [7].

From the 1960s onward, with the rise of large chain stores, the Delta Chinese were faced with severe economic challenges, and the grocery store business began to decline. The political and economic status of African American manual laborers improved as a result of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement [2]. As it turns out, African Americans, the primary customers of Chinese American grocery stores, had other shopping options. The decline in the grocery store business led some Chinese American shop owners to turn to other operations, such as Chinese restaurants, for example Chinese barbecues or Cantonese cuisine [7].

More and more descendants of the Delta Chinese shop owners choose not to run the family businesses. They are more willing to go to college and move to nearby cities, such as Jackson and Memphis [7].

Although Asian Americans are the fastest-growing ethnic group in the South, the Delta Chinese have all but disappeared. With the departure of many Chinese Americans from the region, the economy of the Delta region declined even further [3].

Conclusion

The history of the Delta Chinese is a story of struggle and conquering of that struggle, written by the very people who experienced it. They came into the world at an unpredictable time in history, walked through the wind and rain, and entered into a youthful, dream-filled rise out of adversity.

This history of conquering adversity exemplifies the ability of Chinese Americans to take like a seed to soil to a foreign land, and through struggle eventually become firmly rooted like tall trees.

What is left behind in history is Chinese Americans’ sense of honor, responsibility, and the record of their contributions.

References:

1. James C. Cobb, The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity (1992)

2. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mississippi_Delta

3. YouTube E. Samantha Cheng Interview

6. Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton, Lives of Mississippi Delta Chinese Grocers. John Jung. Yin Yang Press. 2016.

8. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_Asian_Americans

9. http://www.openculture.com/2017/09/learn-the-untold-history-of-the-chinese-community-in-the-mississippi-delta.html