Author: William Tang

Translator: Rosie P. Zhou

Chinatown in the History of Santa Cruz, California

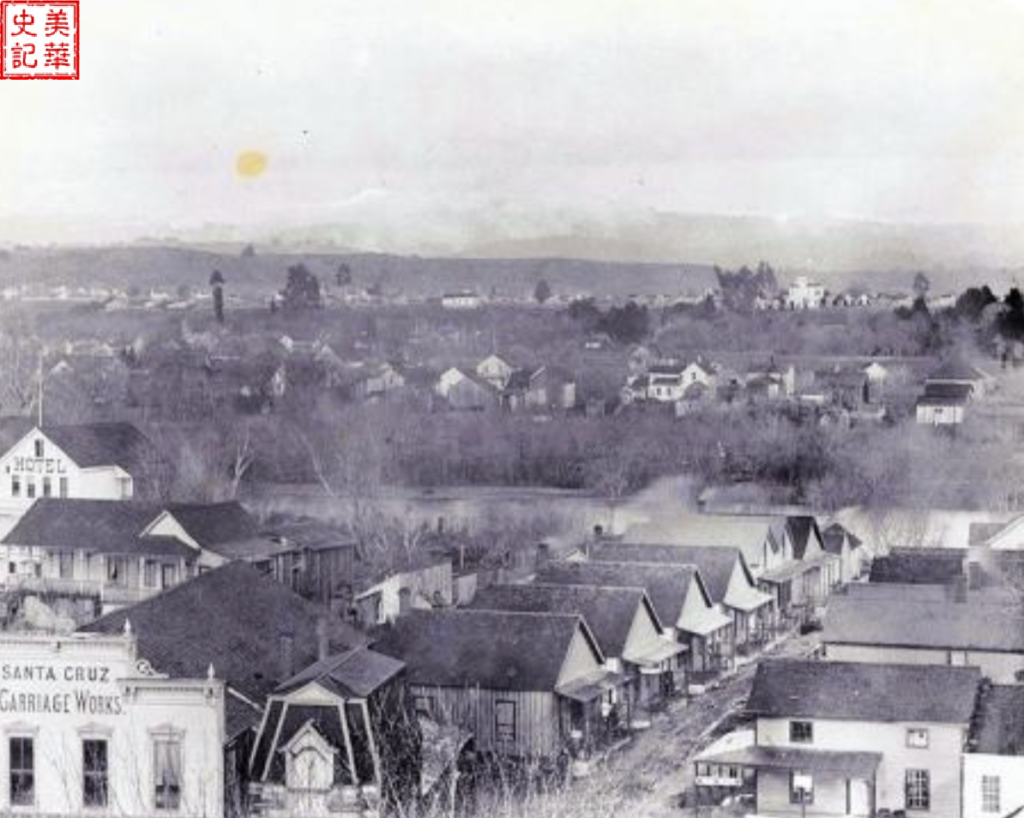

Santa Cruz, a small city near the Pacific Ocean and south of San Jose, belongs to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is a beach city full of joy, tourist attractions, and charming scenery.

Picture 1. The main street of today’s beautiful Santa Cruz was originally the front street of Chinatown. The picture was taken from https://www.alamy.com.

Just like San Francisco, which is famous for its Chinatown, Santa Cruz has also always had a Chinatown throughout its history. However, a fire in 1894 and a flood in 1955 caused the Chinatown of Santa Cruz disappear forever [1,2].

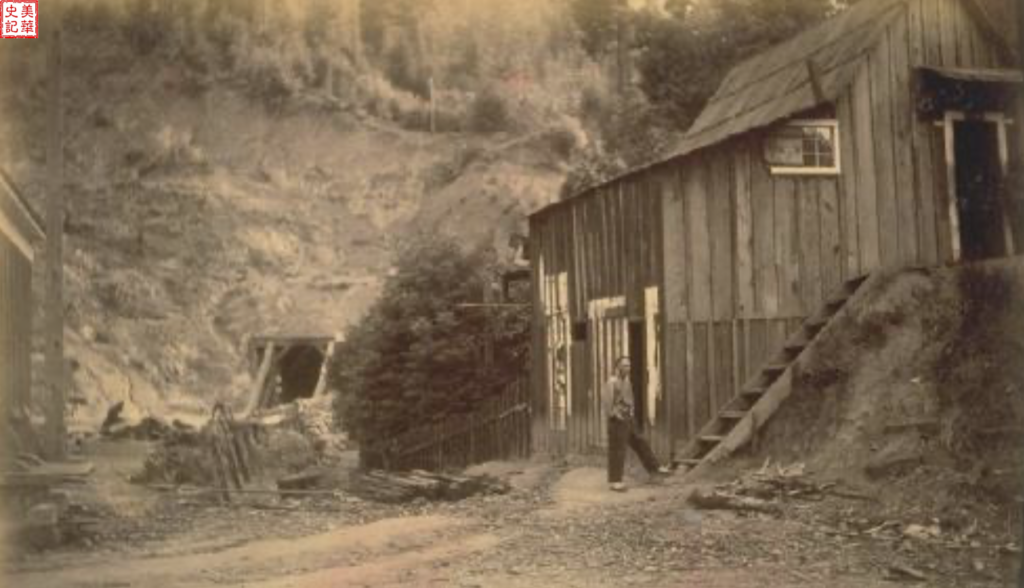

Picture 2. The front street of Santa Cruz’s Chinatown. It was razed to the ground by a fire in 1894. The Loma Prieta mountain is in the background. About 60 people lived in Chinatown. There were three casinos, as well as a laundry room and some boarding rooms. https://brattononline.com/november-26-december-2-2012/

In the present day, the Evergreen Cemetery of the Chinese in Santa Cruz City is the burial place of about a hundred Chinese, including many Chinese workers who worked in gold mines and built railways. Most of the original simple wooden tombstones decayed completely, and only five recognizable wooden tombstones remained, which were later replaced by stone tombstones. On four of the tombstones, only the surnames of the deceased were engraved, without their given names, or their dates of birth and death or places of origin. It is said that in the early years, Chinese workers in the United States changed their names frequently in order to escape arrest by the Immigration Bureau. This may be one of the reasons why their identities cannot be confirmed after death [3, 4].

Picture 3. The Santa Cruz Chinese Evergreen Cemetery, where adventurers who came in the 1800s, including gold prospectors, artists, civil war veterans, lawyers, stonemasons, and so on, were buried. Chinese immigrants were also buried in the Evergreen Cemetery.

Sadly, the United States Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, prohibiting Chinese from entering the country with their family members and from marrying and starting a family with locals. The Chinese Exclusion Act also prohibited Chinese from buying property in the United States. The Chinese workers could only work hard, save money, and send it back to their hometown. They lived frugal, lonely lives in the United States, gradually becoming old and sick, and having nobody to commemorate their deaths.

Back then, the Chinese came to the United States by boat and arrived in San Francisco. When they first arrived, they dreamed of getting rich by rushing for gold, but most people’s dreams fell through. Facing disappointment, the language barrier, and the distress of returning home, they had no other choice but to stay and do any work they could find for subsistence, such as being a cook or a laundry worker.

In 1864, about twelve Chinese laborers set foot in Santa Cruz for the first time to work in a factory. In the 1869’s, a Chinatown where Chinese immigrants lived gradually formed and grew in Santa Cruz. The 1880 census showed that Chinatown was composed of 10 buildings, with 37 men and one woman. Among them, 31 were laundrymen, two were cooks, one was a domestic servant and one was a businessman. In 1880, of the 98 Chinese living in Santa Cruz, less than half lived in the front street of Chinatown. Others lived in the laundry rooms, but most people lived in their masters’ houses as servants. According to the data from the 1889 census, the total population of Santa Cruz was only 4,000, and there were nearly 100 Chinese, indicating that proportionally, the Chinese population in Santa Cruz was not low [5].

Picture 4. The historical Chinatown in Santa Cruz

Chinese Workers Build Wright’s Tunnel

After the wave of gold mining in California gradually subsided, Chinese workers began to transfer to the construction project of the first transverse east-west railway in the United States. (1863-1869). After the east-west railway was completed in 1869, these experienced Chinese railway workers turned to construction of local railways in California.

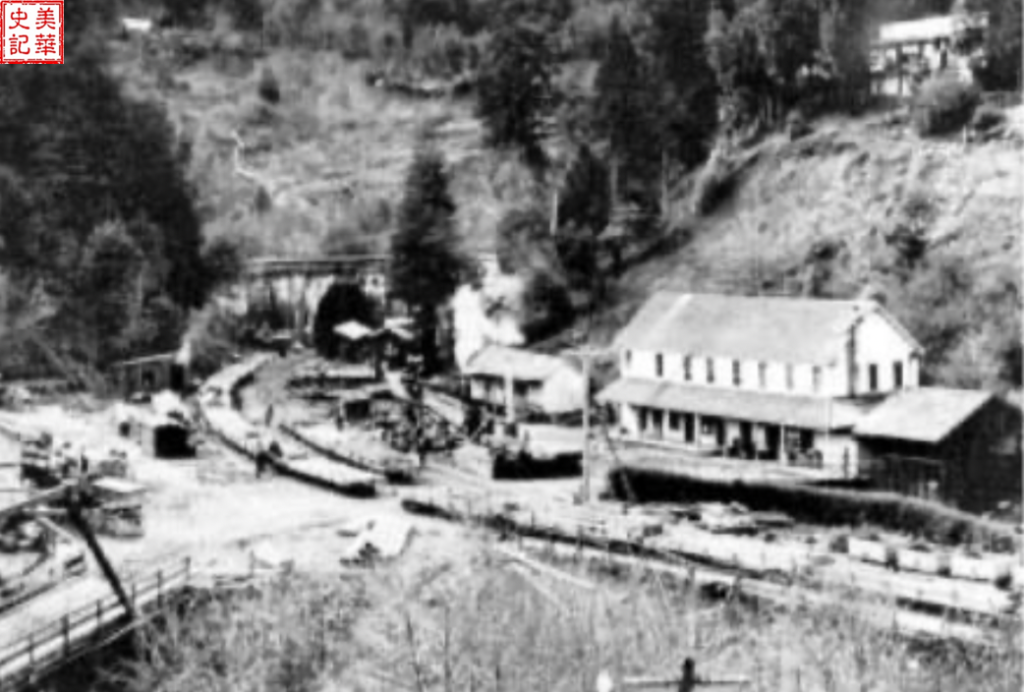

The transportation from Santa Cruz to San Jose used to be on the South Pacific Coast Railroad (SPCRR), a narrow gauge steam locomotive with a gauge width of 3 feet (914 cm). At that time, the railway was built to transport the huge redwoods near Santa Cruz to the densely populated San Francisco Bay Area. Ninety percent of the 1,000 workers who constructed railways were Chinese. The railroad was now abandoned, and the fast California Highway 17 replaced the original railroad.

To the east of Santa Cruz are the Santa Cruz Mountains, where a total of eight tunnels were built for the railway to traverse. Wright’s Tunnel was one of the four main railway tunnels from Los Gatos to Santa Cruz’s railway. It was the longest with a total length of 6,208 feet. The South Pacific Coastal Railway Company recruited 100 Chinese workers to build Wright’s Tunnel [1].

In 1869, Reverend James Richard Wright received 48 acres of land for paying his debts. Wright died on his land, so the land was named after his last name [6].

Wright’s Tunnel passes just below the summit of the Santa Cruz Mountains, so it is also called the Summit Tunnel. It took 27 months to develop this tunnel from 1877 to its completion in 1880.

Picture 5. View of the South Entrance of Wright’s Tunnel from the outside

Picture 6. View of the South Entrance of Wright’s Tunnel from the inside

On a rainy day in December 1877, Chinese workers began to blast the mountain and dig a hole. Due to the sandy soil, the speed of workers’ digging was not as fast as the rate of rocks collapsing and backfilling, and the progress of the project was very slow.

Despite switching day and night shifts, they were only able to dig five and a half feet deep into the mountains every day. At first it looked like a 10-month project, but it was estimated that it would take at least three times that amount of time, and that the final cost would far exceed the funding.

Railway companies needed cheap, obedient, efficient, and reliable Chinese workers who earned only 77 cents a day [6, 7].

Picture 7. A Chinese worker who worked on Wright’s Tunnel. By Frank B. Rudolph, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

After going deep into the cave, surprisingly, the exposed rock changed and turned into black coal. Chinese workers often fainted and discovered that methane gas was seeping out of the cave. The methane in the cave had to be burned out from time to time before they could enter the cave and continue to work. The working environment was extremely dangerous.

By mid-November 1878, when the tunnel reached a depth of 2,300 feet in the mountain, an oil-like substance began to seep out from cracks in the rock quite regularly, and a layer had to be burned every 5 to 10 minutes to prevent the dangerous layers from accumulating.

On the night of February 12, 1879, an inevitable tragedy occurred. While igniting the explosive’s fuse, the foreman, in the middle of his shift, accidentally ignited a bag of gas. The flame from the explosion fired like a cannon full of gunpowder. The foreman survived somehow, but none of the five Chinese workers on sight survived.

On November 17, 1879, one minute before midnight, a team of 21 Chinese workers and two white men detonated an explosive at a depth of 2,700 feet. The fire ignited a large area of gas, causing a loud noise accompanied by earth-shattering vibrations. When two white men stumbled in a severely burning tunnel, 20 Chinese workers rushed inside from their side and tried to rescue their compatriots. These brave souls had just entered 1,500 feet into the tunnel when a second larger explosion occurred, shaking the entire mountain [6].

The 20 Chinese workers ran out of the cave quickly. Some of the other Chinese workers had no time to escape and were blown up alive, while some were severely burned by the flames from the explosion, and begged their companions to kill them immediately to relieve the pain. The scene was terrible.

The next morning, the railway company placed multiple gigantic mirrors at the entrance of the cave to reflect sunlight into the cave and search for the victims. As a result, a total of 32 charred Chinese workers’ bodies were found. The earth-shattering tragedy came to an end, and the remaining Chinese workers, who were extremely frightened, left one after another. The company later asked a sorcerer to recite scriptures to collect the deceased workers’ souls, according to Chinese customs, but it was still unsuccessful in persuading the Chinese workers to return to the cave to continue working.

The 32 Chinese workers who lost their lives, together with the five Chinese workers killed in the bombing on February 12, 1879, were killed at the site for the construction of Wright’s Tunnel. Their remains were buried hastily along the rails north of the now-abandoned Wright’s Station. Their graves can be seen on the train many years later. They were swallowed by the mountains and forgotten by people over the years [6].

In January 1880, the company brought a new group of Chinese workers to complete this cursed tunnel, and their daily wages were increased to $1.25 U.S. dollars. They burned incense and carved prayers on the supporting wood in order to drive away the demons. But the curse was too strong, and the frightened people refused to enter the tunnel, let alone complete the project.

The company had no choice but to transfer these Chinese workers to the South Entrance to work, and they recruited new Cornish workers to work at the North Entrance, where the explosion had taken place. Cornish workers progressed at an average of 4 feet a day, while Chinese workers progressed at a rate of 8 feet a day.

On March 13, 1880, Cornish workers and Chinese workers blasted a hole in the last stone separating the north and south ends of the tunnel, and the two groups of workers met in the mountains. At the end of April, the tunnel was finally completed and opened. The celebration of the completion of the mountain railway failed to mention the dozens of Chinese who lost their lives in its construction [8].

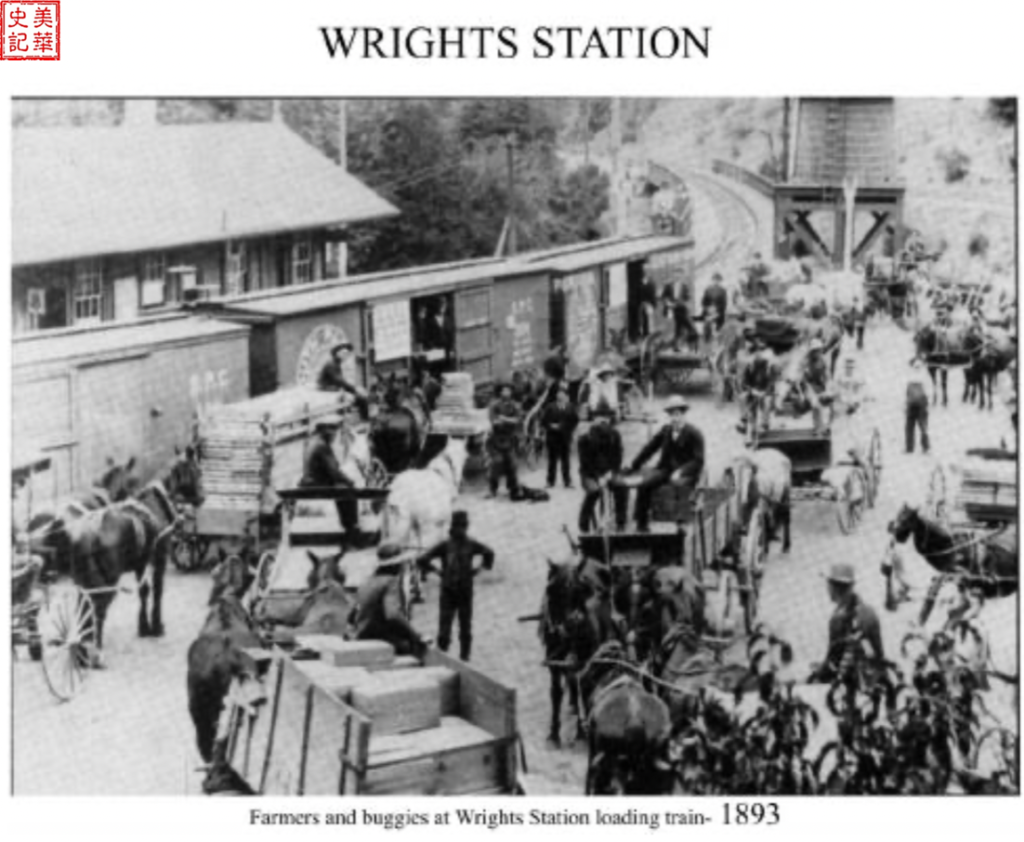

Picture 8. Wright Railway Station, which no longer exists, in 1893.

The Hungry Ghosts in the Tunnel

The Chinese have a saying that if people die away from their families, then their helpless and neglected souls will become hungry ghosts, and they will do evil until their bodies are reunited with their families. In the second year, this statement was unfortunately true. On May 23, 1880, a terrible train accident occurred on the new railway, which killed 15 passengers and injured more than 50 people. The accident haunts and stains the railway tunnels, which were supposed to be something to be proud of in Santa Cruz’s history.

Picture 9. An artist’s rendering of the accident that occurred on the newly built South Pacific Coast Railroad on May 23, 1880. It is said that this accident was caused by the anger of the hungry ghosts of the Chinese who died in the tunnel in 1879 [8].

In April 1906, a 7.9 magnitude earthquake occurred in San Francisco. After the earthquake, the tunnel was closed for two years. The North Entrance closed because geologists discovered that at the junction of the Western Pacific Plate and the New World Plate, the San Andreas Fault, which is about 1,050 kilometers long, moved laterally under the tunnel, 6 feet, just near the North Entrance of the tunnel.

Figure 10. View of the North Entrance to Wright’s Tunnel from the inside.

Picture 11. Wright’s Railway Station in 1907, with Wright’s Tunnel in the background. By Greg De Santis.

On April 4, 1942, the U.S. army detonated a large amount of explosives in the cave about a hundred feet away from the entrance, blowing up the entire tunnel, and permanently sealing the tunnel. They destroyed what the Chinese workers had achieved in a single day, which took 27 months and the sacrifice of dozens of lives. Except for the mention of them in the writings of some historians, the people who died in the tunnel have never received any recognition or due respect for their work [6].

Local historian Sandy Lydon pointed out that Chinese immigrants believe that the lone souls of the Chinese workers who died in the Wright tunnel were homeless and became hungry ghosts, still living in the tunnel, waiting to reunite with their relatives and be brought home, one by one [8].

Today, among American explorers travelling, some have taken pictures of bizarre lone souls in the cave, and others have taken pictures of steam engine trains just entering the tunnel at the entrance of the cave, leaving behind a mixture of coal-burning smoke and steam.

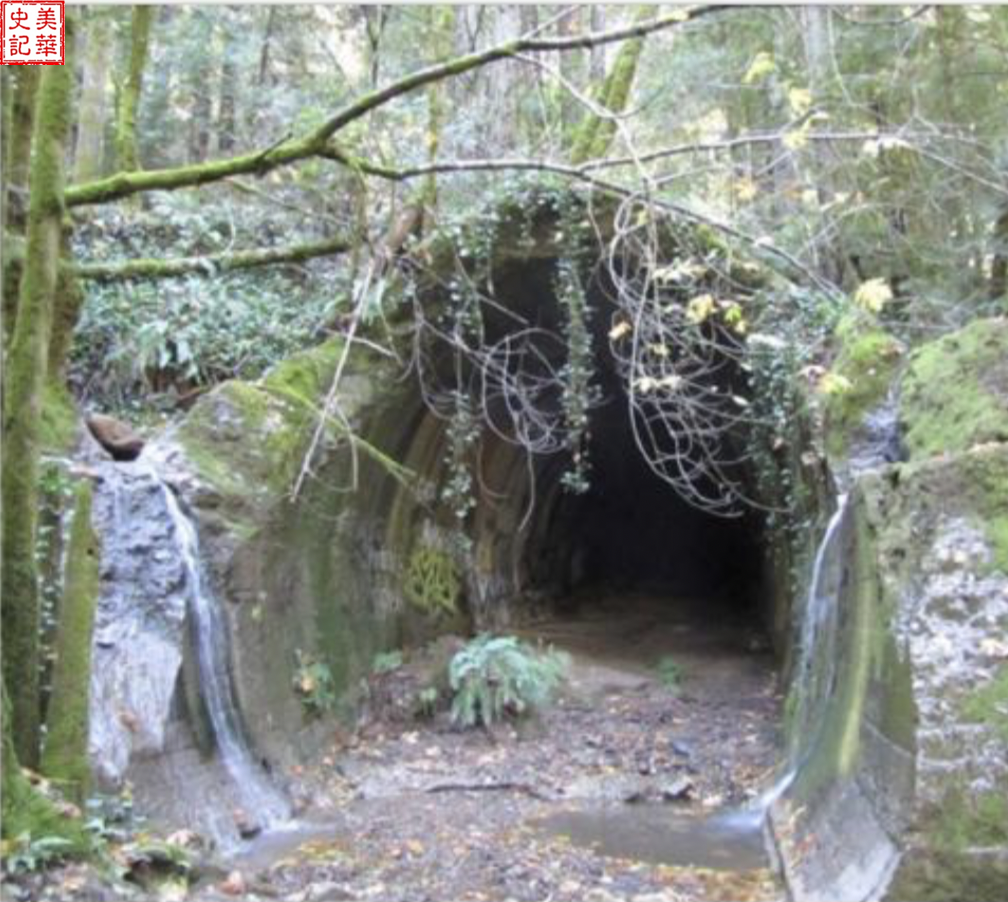

Now, the north entrance of Wright’s Tunnel is overgrown with weeds, with tree roots entangled and staggered covering the roof of the cave. The cement wall inside the cave is full of graffiti. There are still broken rails and a few discarded railroad ties half-buried in the mud in the stream in front of the cave; the sight is desolate and chilling.

Figure 12. View from the outside of the North Entrance of Wright’s Tunnel.

REFERENCES

- Wright’s Tunnel https://exploreapaheritage.com/index.php/sites/wrights-tunnel/

- Greg Pepping. Chinatown Bridge Update. May 18, 2020. https://coastal-watershed.org/chinatown-bridge-update/

- An Inspiring Place. https://www.santacruzmah.org/evergreen

- 萍萍。《追尋華工遺跡》 2019年10月6日《世界日報》F3 世界副刊

- Susan Lehmann. Economic Development of the City of Santa Cruz, 1850-1950. https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/files/original/3d763c4590f66443f14512a0a2e530fe.pdf

- Ryan Masters. The history of Wrights Tunnel in the Santa Cruz Mountains—once the second longest railroad tunnel in California—is a tale of death, greed and bigotry. https://hilltromper.com/article/horrors-summit-tunnel

- In Memoriam: Chinese Train Tunnel Workers heathenchinese.Wordpress.com

- Gas and Ghosts in the Santa Cruz Mountains. http://www.sandylydon.com/new-page-18