Zhida Song-James

This article presents several historical cases from 1875 to 1905. After the signing of the Burlingame Treaty in 1869, large numbers of Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States. Later, the United States promulgated a series of laws to limit Chinese immigration, each increasing the restrictions on Chinese immigrants. Chinese persons, residents and citizens alike, were continuously being denied and detained upon entry. They filed multiple lawsuits in U.S. courts challenging the constitutionality of these immigration laws.

22 Chinese Women v Freeman (Chy Lung v Freeman), 1875

Picture 1. Hong Kong to San Francisco Line opened in 1867; San Francisco became the Gateway for Chinese immigrants to the U.S. Sources: Smithsonian Institute Libraries, https://americanhistory.si.edu/onthewater/exhibition/5_2.html

The case occurred before the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and was the first brought to the U.S. Supreme Court by Chinese immigrants. The appellants were 22 Chinese women.

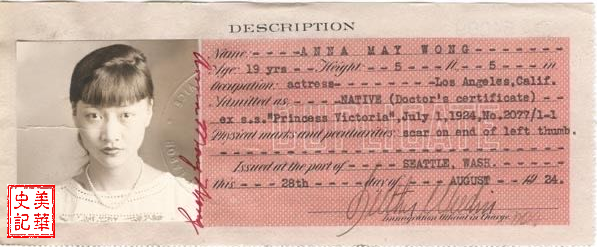

On August 24, 1874, the steamer “Japan” from Hong Kong docked in the port of San Francisco to await immigration inspection. Almost all 600 passengers on board were Chinese,1 and 89 were women. The “22 Chinese Women’s Case” began here.

Boarding the ship was California immigration commissioner Rudolf Piotrowski, a native of Poland, with his assistants and interpreters. He found that 22 women among the passengers were traveling alone, not companied by their husbands or children, which he considered suspicious. From his exam, he decided these were prostitutes. He then asked the captain to pay a $500 bond for each of them before allowing them to disembark. The captain refused; Piotrowski ordered the women detained on board and forced them to return to Hong Kong. That’s because, he said, the women were, by his judgment, “lewd and debauched women.”2

Piotrowski relied on California statute, “An Act to Prevent the Kidnapping and Importation of Mongolian, Chinese and Japanese Females for Criminal and Demoralizing Purposes.”3 Under the decree, all immigrants were subject to inspection by California immigration officials when they disembarked, and each must pay a 75-cent inspection fee. Immigration officers had the power to prohibit “certain travelers” from disembarkation unless each paid a bond of $500 in gold. These travelers primarily refer to women, whom immigration officials consider lewd.4 In many cases, California immigration officials couldn’t distinguish whether a traveler was a “lewd and debauched woman,” only arbitrarily labeling Asian women as such. This situation happened after the Transcontinental Railroad’s completion and before the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, California passed and implemented various laws to extort and restrict Chinese immigrants. Such rules included a high Foreign Miner tax for Chinese miners, a fishing tax on Chinese involved in fishing, and an additional Chinese police tax for most “Mongols.” There were also legislations prohibiting Chinese from testifying for Whites in criminal or civil cases and denying Chinese children access to state schools. Rumors spread that many Chinese were entering California to take jobs from Americans and that, as outsiders, the Chinese were threatening American morality and civilization with their language and culture.

These California anti-Chinese laws were contrary to the policy of the U.S. Federal Government. The Burlingame Treaty in 1868 formally established equal and friendly relations between China and the United States. Citizens of both countries could go to school in each other’s countries, enjoy the most-favored-nation treatment, and free immigration for people from both countries. The treaty opened the door for Chinese laborers to immigrate to the United States. Domestically, it was nearly a decade after the Civil War’s end, and the southern states’ reconstruction had largely been completed. The Federal Government has been increasingly powerful. Moreover, “state rights” had long been a pretext used by the South slave-holding states against the Union. By the middle of the century, California’s immigration laws aimed at deporting or suppressing Chinese were self-contained, ignoring federal government treaties and directly colliding with growing Federal power.

The day after Piotrowski ordered the detention of the 22 women, local Chinese, possibly Chinese businessmen, hired a lawyer and sued out a writ of habeas corpus on their behalf. During the four-day trial in San Francisco, the women’s lawyers argued fiercely with the State’s attorney. The battle centers on three main issues: what were the state power vs. the federal authority, the women’s freedom and their rights, and whether rapid screening by immigration officials was sufficient to make the judgment about these immigrants’ character.

The State argued that California had the right to protect itself from “despicable immorality.” Chinese women’s lawyers countered that their clients had legitimate tickets and identification. Under the treaty between the United States and China, it was their “inherent and inalienable right” to reside as individuals in a country they chose. The travel unaccompanied was not sufficient evidence to support the immigration commissioner’s judgment. The women called to the witness stand protested the insult to their reputation by California immigration officials and insisted on their innocence. Some said their husbands were in China or the United States. When a woman named Ah Fook told the Court that she had come to San Francisco with her sister and intended to make a living as a tailor, she burst into tears and cried in anger, insisting that she had no other purpose. Her tears triggered sadness and irritation due to their humiliation; many couldn’t help but cry. For a while, the sad voice filled the courtroom. Judge Robert F. Morrison hurriedly left the bench and ordered the women to be temporarily removed from the courtroom to calm them down.

Judge Morrison held that the women were not U.S. citizens and were not protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. As the trial progressed, determining whether they were “lewd” became the critical legal basis. A former missionary in China testified that it was customary for slutty women in China to wear flashy clothing to attack attention; however, not all witnesses agreed. With the judge’s consent, a lawyer examined the garment of several of them. He found some colorful clothes under their coat. Based on the clothes, Morrison ruled against the women: they were indeed “obscene,” he said, and the State’s laws were justified in safeguarding California’s “well-being and safety.” 5

Morrison allowed the women to disembark and handed them over to the San Francisco Sheriff to wait for the return of stream boat “Japan” and send them back.6 The women refused to return; the California Supreme Court denied their appeal a week later. But the women remained steadfast and petitioned the Federal Circuit Court of the District of California.

Stephen J. Field, nominated by President Lincoln to the Supreme Court in 1863, was hearing lower court cases. The case came to his desk. First, he acknowledged the right of State Governments to invoke the so-called “sacred law of self-defense” that prisoners, lepers, people with incurable diseases, and who had committed crimes were not allowed to enter, lest they become a public charge. But he declared that Congress had exclusive power to regulate immigration.

In the ruling, Justice Field expressed his opinion: except for the aforementioned State’s right, any other factors affecting the dealings of immigrants were under the jurisdiction of the U.S. government. They were not controlled or interfered with by the State. In Field’s view, the governments of some states at the time (formerly slave-holding States) were trying to exclude blacks from the freedoms they were entitled, and there were similarities in California immigration laws. He noted that the state government’s mistreatment of foreigners could lead to “the most serious consequences,” including war. The law was required to protect the Union from these states’ wrongdoing as if it was not bound by some provisions in State statutes that prevented blacks from gaining their liberty. Field concludes that the California statute violated the rights of these women under the U.S.-China treaty, the recently passed Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the 1870 Code of Confederation. He ordered the Sheriff to release the women. 7

The treaty between the United States and China refers to the Burlingame-Seward Treaty of 1868 (or Burlingame Treaty), as a revision of the Sino-American Treaty of Tianjin, by Anson Burlingame, in his capacity as China’s first plenipotentiary minister for foreign affairs, and Secretary of State William Henry Seward, representing the United States, signed in Washington on July 28, 1868. It was the first relatively equal foreign treaty of the late Qing dynasty.8

The Burlingame Treaty established reciprocity between the two countries through Western international law. The treaty established formal friendly relations between the two countries, with the United States granting the most-favored-nation status to China. Its primary contents include: China maintained “Eminent Domain” over all its territory, including the land resided by foreigners in China; China had the right to appoint consults at U.S. ports; liberty of conscience, protecting citizens of both countries from religious persecution in each other’s territory; free immigration; citizens of both countries could attend each other’s public schools and enjoy the most-favored-nation treatment, and citizens of both countries could set up schools in each other’s territory. The U.S. government would not interfere with China’s internal affairs, and China would independently manage its construction projects. If the Chinese Government wanted to take advantage of Western technology, the U.S. government would assist.

After the signing of the Burlingame Treaty, the United States became the first choice for the Chinese Government to send students studying abroad. In 1872, the first Chinese children sailed to the United States. The treaty also opened the door for Chinese laborers to migrate to the United States. California violated this treaty by denying the women’s entry without evidence.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted on July 9, 1868, 9 was one of three reconstruction amendments after the Civil War. This Amendment deals with civil rights and equal legal protection and has profoundly impacted American history. It has since been the basis for many judicial cases. In particular, the first of these provisions, also known as Equal Protection Provisions, requires states to protect everyone under equal law in their jurisdiction and is one of the most litigated provisions of the U.S. Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution provides that no State may deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor may it deny any person equal protection within the law.

Justice Field explained that this equal protection meant that all people had equal access to the Courts to prevent or correct wrongs and to exercise their rights and that all people were equal in their immunity from charges and burdens. He noted that the Enforcement Act, passed by Congress on May 31, 1870, declared that no State could impose and coerce any additional conditions unequally and that any state acts that contradicted the congressional act were declared null and void. California’s requiring certain people to pay a bond to land contradicts this congressional act.

The anti-Chinese media in San Francisco was furious about the decision. The twenty-two Chinese women didn’t stop there either. Their representative, Chy Lung, challenged the constitutional basis of California’s law. Justice Field also wanted to know if his Supreme Court colleagues would agree. In 1876 the case was brought before the Supreme Court as Chy Lung v Freeman (92 U.S. 275 (1876)). 10 The case marks the first time a litigant from China appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court.

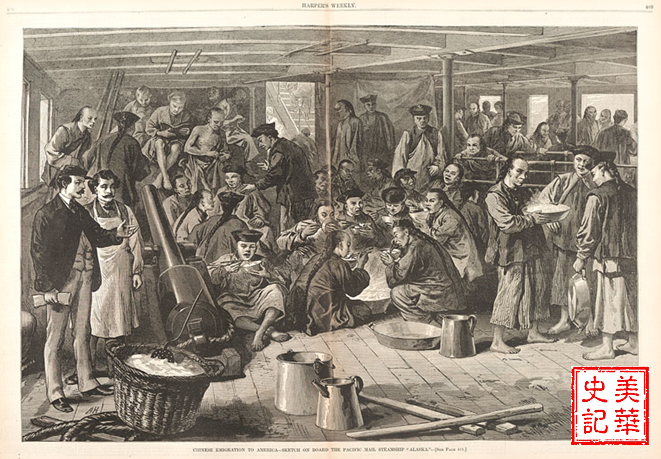

On March 20, 1876, nine Supreme Court judges unanimously ruled to overturn the California Supreme Court’s decision, and twenty-two Chinese women finally won. Justice Samuel Miller, who authored the ruling, argued solemnly that California’s statute was contrary to the Constitution, and he discussed the basis for the ruling in three ways:

First, immigration policy and foreign relations with other countries were solely the authority of the U.S. Congress, and the responsibility to execute immigration and regulations solely belonged to the national Government, not the State. Therefore, California did not have the authority to admit or impose restrictions on immigrants. The Supreme Court noted that California’s actions could violate U.S. government treaty obligations and harm U.S. government foreign relations. The Supreme Court held that while states can enact reasonable and necessary regulations for those who might become a burden of public and convicted criminals, California statutes go far beyond that.

Picture 2. U.S. Supreme Court Justices 1876. Stephen J. Field and Samuel F. Miller are second and third left, respectively. Sources: U.S. Supreme Court, https://www.supremecourt.gov/visiting/exhibitions/GroupPhotoExhibit/section1.aspx

Second, California statutes make immigration officials make decisions based on superficial impressions, lacking due process. It inflated the power of petty government officials, allowing them to do whatever they wanted. Miller wrote: “The commissioner has but to go aboard a vessel filled with passengers ignorant of our language and our laws, and without trial or hearing or evidence, but from the external appearances of persons with whose former habits he is unfamiliar, to point with his finger to twenty, as in this case, or a hundred if he chooses, and say to the master, ‘These are idiots, these are paupers, these are convicted criminals, these are lewd women, and these others are debauched women.'” He said immigration officials “deciding whether a young woman’s manners are such as to justify the commissioner in calling her lewd may be made to depend on the sum she will pay for the privilege of landing in San Francisco” is systematic extortion.

Third, California’s actions degrade America’s global standing and may provoke retaliation. The Court ruled that if the state government had the right to deny immigration entry, “a state … embroil us in disastrous quarrels with other nations.”

Picture 3, 22 Lewd Chinese Women: Chilung v. Freeman, 1876, historical reenactment, Asian American Bar Association of New York

Can such a California immigration law be said to be good if it dangerously usurps federal control, allowing officials to abuse their power at will based on their perceptions and use the statute to extort money? Miller concluded. The decree “contradicts the U.S. Constitution and is therefore null and void.”

Following the decision, all 22 Chinese women involved regained their freedom.

However, the federal administration of immigration did not guarantee immigrants’ rights. Almost at the same time as this case. Congress passed the Page Act, 11 the first of a series of laws to restrict immigration. Since then, all Chinese women who came to the United States must be screened in Hong Kong.

Treaties and Acts on Immigration After 1875

In November 1880, James Burrill Angell, a negotiating envoy representing the United States, met in Beijing with Li, Hongzao, a Grand Minister of State representing the Qing government of China, to discuss amendments to the Burlington Treaty. On November 17, the two sides signed the Treaty of Angell, officially known as the Treaty of Regulating Immigration from China of 1880. 12 Under this treaty, the U.S. government could regulate, restrict, and suspend Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States and still accept merchants, scholars, and other personnel to immigrate. Although the treaty also reaffirmed the continued commitment of the United States to protect the rights and interests of Chinese laborers already in the United States. Through this treaty, Sino-US trade was separated from free immigration; as a result, it became more difficult for the Qing government to support the rights and interests of Chinese laborers in the U.S. It opened the door for pass of a series of Chinese exclusion laws later.

Picture 4, James Burrill Angell represented the U. S. in negotiating and signing the Treaty of Regulating Immigration from China. 1875.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese laborers altogether. First and foremost, it affected Chinese who had left the United States temporarily, making their return to the United States complicated and increasingly difficult.

The Scott Act 13 was introduced in 1888 to supplement and extend the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. After it became a law on October 1, 1988, 20,000 to 30,000 Chinese immigrants were stranded and unable to return to their residence in the United States.

The 1892 Geary Act 14 extended the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by adding requirements and restrictions on Chinese nationals in the United States. One of them was that the Chinese must obtain and carry a government-issued resident certificate at all times; otherwise, they could be deported or punished by doing hard labor. Geary Act also prohibited Chinese from testifying in court. By this provision, the U.S. government added the burden of proof of legal residency onto Chinese immigrants.

Between 1884 and 1905, the Chinese repeatedly fought against these discriminatory laws and restrictions through judicial courts, especially applications for habeas corpus. They took their cases to the Supreme Court several times. But increasingly harsh immigration laws continue to press their living space. Under the U.S. justice system, every court decision could be cited to justify restriction for the latter cases. The following cases are examples.

Chew Heong v U.S., 1884

On September 22, 1884, Chew Heong arrived in San Francisco. He had traveled from the United States to Honolulu, then the Kingdom of Hawaii, on June 18, 1881, and stayed there until September 15, 1884. When the ship anchored, he was denied entry and detained on board. According to the Chinese Exclusion Act of May 6, 1882, Chinese immigrants must have return permits issued by the Government before leaving the United States, without which they could not land in the United States. Chew Heong believed that under the treaty between the two countries, Chinese nationals visiting or residing in the United States enjoyed the most-favored-nation treatment, including freedom of travel. He filed a petition for habeas corpus in the California District Court, claiming that he was not subject to the restrictions of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and that the detention was unlawful deprivation of his liberty. The California District Court judges disagreed on whether to issue the writ of habeas corpus, and the case was eventually brought before the Supreme Court.15

The case preceded the Scott Act. The Supreme Court held that Chew Heong had left the United States for Hawaii before passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; therefore, he did not require a return permit to re-enter the United States. They refused to retroactively operate the regulations on the base of the Chinese Exclusion Act, ruling that the plaintiffs had the right to go ashore, enter and remain in the United States. In this case, the Supreme Court rejected the immigration official’s decision.

Chae Chan Ping v U.S., 1889

This case occurred after the passage of the Scott Act. Chae Chan Ping, a laborer, moved to San Francisco, California, in 1875. He was in the United States from 1875 to June 2, 1887. Following the Chinese Exclusion Act provisions, Chae obtained a re-entry permit before leaving the United States for China. When the Scott Act was passed, he was on the steamship “Belgic” back to the United States from Hong Kong. Chae Chan Ping arrived at the port of San Francisco on October 8, 1888, presented his permit and requested to enter the United States. Port officials not only denied his entry based on the Scott Act but also forbade him from entering the United States in the future. He was detained on board by the ship captain. Chae Chan Ping applied for habeas corpus, asking the captain to release him and allow him to appear in Court. The captain complied; however, the Court found that he had not been deprived of his liberty and returned him to the captain. With the support of the Chinese community, he appealed, and the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court.16

In May 1889, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the lower court’s decision. After detailing the background and content of the Angell Treaty, they stated that the U.S. government could replace the provisions of previous treaties with new legislation. Treaties were considered valid laws only until new legislation became effective. The Burlington Treaty had been amended in 1880; under Angell Treaty, the Chinese Government recognized the right of the United States to regulate and restrict Chinese immigrants. They noted the treaties between the U.S. and other nations as precedence that the U.S. government indeed had the power to regulate immigration for the national benefit. The U.S. government, through legislative action, could exclude aliens from its territory, which the Court affirmed to be the undisputed exercise of sovereignty. Finally, the Court decision stated that the judiciary was not the appropriate forum to appeal any violation of the provisions of international treaties, and diplomatic issues should be resolved between the governments concerned.

Justice Stephen J. Field wrote the Supreme Court ruling; he was the justice who had ordered the release of 22 detained Chinese women in 1875. Through this case, the Supreme Court established the full legislative power of Congress to make immigration laws and the power of the Government as the executive to amend provisions in international treaties. This decision became a key precedent for subsequent immigration litigations. If the judicial system was still a channel for the Chinese, especially the Chinese laborers, to defend their rights, this decision significantly narrowed this channel.

Fong Yue Ting v U.S., 1893

This case occurred after the Geary Act came into force. Fong Yue Ting and two other Chinese nationals living in New York City were arrested and detained because they did not have resident certificates. All three applied for habeas corpus in Court.

Fong Yue Ting came to the United States before 1887 and lived in New York. He neither held nor applied for a resident certificate. The law enforcement officials arrested him. The other Chinese was in a similar situation, except a local court had approved his arrest. The third Chinese had applied for a resident certificate but did not receive it. The witnesses he presented were all Chinese; because he didn’t have two white witnesses to testify for him, the testimonies by the Chinese were deemed invalid. He was arrested regardless. All three appellants argued that their arrest and detain were without the due process of law. The Geary Act provisions, which the law enforcement relied on to justify their arrests and detentions, were contrary to the Constitution. It should therefore be null and void.

The Supreme Court decision (5 : 3) upheld the Geary Act provision and rejected habeas corpus.17

The ruling cited the Chae Chan Ping case as a precedent. It was within the Federal Government’s power to regulate immigration, including setting conditions for foreigners to live in the United States. The Court rejected the similarities of this case with Chy Lung v Freeman, in which the Supreme Court explicitly ruled that states had no authority to impose restrictions on immigrants beyond those provided for in federal immigration law. By 1893, Congress has passed a series of bills to exclude and restrict Chinese immigrants. The Supreme Court majority believed that the New York authority’s actions were consistent with federal law at the time. It also held that the lower Court’s decision did not infringe on Fong Yue Ting and the others’ right to equal protection from the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

The three justices opposed the majority ruling from different angles.

Justice David J. Brewer put it plainly: the decision was “a blow against constitutional liberty.” The Geary Act itself was unconstitutional. Resident aliens should be fully protected by the Constitution. Section 6 of the Geary Act deprived their liberty by ignoring the rights guaranteed by the Constitution, particularly articles in the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 8th of the Constitutional Amendments, without due process of law.18 He wrote, “I am of the opinion that the orders of the court … should be reversed, and the petitioners should be discharged.”

Justice Stephen Field held that the Federal Government had the authority to set conditions for immigrants to reside, determine whether they were in the country illegally, and deport them. However, he argued that the criteria for the deportation of U.S. residents should be higher and stricter than the criteria for refusal of entry. Deportation simply because one did not have a certificate was an excessive penalty. Precedent cases were about admission rather than expulsion and, therefore, not applicable to this case. He also noted that the procedure introduced in the Geary Act was insufficient to be due process.

Another justice, Melville Fuller, argued that the Geary Act itself was inappropriate. “No euphuism can disguise the character of the Act in this regard. It directs the performance of a judicial function in a particular way and inflicts punishment without a judicial trial.” It was “a legislative sentence of banishment and absolutely void.” He also expressed concern that the Geary Act contained “germs of unlimited and arbitrary powers,” arguing that the Act was generally “incompatible with the immutable principles of justice, inconsistent with the nature of our Government, and in conflict with the written Constitution by which that Government was created and those principles secured.”

The discernment and impartiality of these justices were the light of justice in the wave of Chinese exclusion.

Lem Moon Sing v U.S., 1895

Lem Moon Sing was a Chinese merchant living in San Francisco who worked at Kee Sang Tong Co., a retail and drug company. On January 30, 1894, he left the United States for China. While he was away, Congress passed Appropriations Bill on August 18, 1894, which included expenditures earmarked for implementing the Chinese Exclusion Act. It specifically stated that in every case “where an alien is excluded from admission into the United States under any law or treaty now existing or hereafter made, the decision of the appropriate immigration or customs officer, … shall be the final.” Only the Secretary of Treasure could reverse such decisions.

Lem arrived in San Francisco on November 3, 1894. He submitted testimony to customs officials from two non-Chinese witnesses, confirming that he had indeed been a businessman and had not worked as a laborer during the year before leaving the United States. But he was denied entry and detained on board. In his appeal, Lem stated that he was not a laborer barred from entering the U.S. under the Chinese Exclusion Act. Moreover, the inaccessibility would devastate his company and livelihood, and his detention deprived him of his liberty and violated the Constitution. Finally, his case was submitted to the Supreme Court.19

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal. The judgment cited the above Fong’s case as a precedent and decided that denying his entry did not violate his freedoms and constitutionally guaranteed rights, and reaffirmed the discretion given to immigration and customs officials to grant or deny entry of immigrants.

Reviewing the above cases, one can observe how a series of laws beginning in 1882 have systematically strengthened restrictions and exclusions of Chinese and Chinese Americans. Under such circumstances, the judicial system had been an important channel for the Chinese to fight against such limitation and exclusion; the most common way was habeas corpus petitions. Some Chinese have successfully obtained help through the court. But the Supreme Court’s ruling in U.S. v. Ju Toy was a turning point.

United State v Ju Toy, 1905

Ju Toy was a U.S.-born citizen. One would say that as a Chinese American, neither the Chinese Exclusion Act nor the Scott Act would affect him. In 1905, Ju Toy returned to San Francisco by ship after visiting China. Although he was not an immigrant, port officials denied his entry and ordered his expulsion. Ju Toy then filed for habeas corpus in Federal District Court, which ruled that Ju Toy was American and ordered his release. However, the Government appealed the ruling, and the case was submitted to the Supreme Court on April 3, 1905. The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the Government, holding that habeas corpus applications should be dismissed. 20

The ruling found that Ju Toy’s application only mentioned his citizenship but did not disclose abuses of power by government officials or the existence of unsubmitted evidence. The Supreme Court held that while laws passed by Congress did not give executive officers the power to deny a citizen’s re-entry, they indeed gave them the power to decide whether a person was a citizen. Therefore, the refusal of Ju Toy’s application for entry without a judicial hearing did not amount to a denial of due process; even without a judicial trial but denying a citizen’s re-entry, it still was due process. Justice Oliver W. Holmes wrote in the ruling that even if Ju Toy was a Native American, the Court could not help because the immigration officer’s conclusion was decisive and not subject to judicial review.

Three justices, Brewer, Rufus W. Peckham, and William R. Day, dissented from the majority ruling. They argued that Ju Toy had been judicially determined to be an innocent free-born American citizen. Returning to one’s country was not a crime for citizens. Brewer argued that allowing an innocent citizen to be deported without a jury trial and judicial hearing ultimately deprived him of his rights as a citizen.

Picture 5, Justices David J. Brewer (left,1888) and William W. Ray (right, 1899)

The importance of this case lies in the fact that the Supreme Court had relinquished its power of judicial review of immigration matters. The Supreme Court held that the immigration officer’s refusal of entry to the applicant at the port did not amount to a denial of due process and confirmed that the immigration officer’s findings were definitive. The decisions were not subject to judicial review unless there was evidence of their bias or negligence. The case marked a significant shift in the Court’s dealing with appeals filed by habeas corpus petitioners, completely changing the justice system’s role when citizens apply for entry and face deportation.

After the ruling, criticism poured in, with critics arguing that the Court had seriously deviated from constitutional principles. The main arguments focused on Holmes’ controversial opinions that a simple administrative process of immigration officials to examine applicants would satisfy “due process,” and it was no need to grant applicants judicial hearings. Before this case, the courts had distinguished the constitutional rights of citizens from aliens, holding that aliens could not use the Constitution to protect themselves from administrative decisions. In this decision in Ju Toy, the Court blurred the distinction between aliens and citizens.

After this case, the Federal Court was no longer involved in investigating whether the person had the right to enter the United States, and the immigration officer’s decision became final. Additionally, the Ju Toy ruling empowered immigration officials to decide whether an applicant was a citizen who previously had a legal entry. This practice severely limited the opportunities for the Chinese to appeal the entry decisions in Courts. After U.S. v. Ju Toy, the number of Chinese habeas corpus petitions filed by the Northern District of California dropped from 153 in 1904 to 32 in 1905 and 9 in 1906. With routine denies to their habeas corpus petitions by the San Francisco District Court, the possibility of getting a judicial hearing for Chinese immigrants has largely disappeared.

Conclusions

In 1875, the Supreme Court ruled that California could not enact its own immigration laws and deny Chinese nationals entry, and 22 Chinese women won their case. In 1884, the Supreme Court ruled that immigration officials couldn’t apply the Chinese Exclusion Act retroactively to deny the Chinese right to travel freely garmented by the Burlingame Treaty. Until then, the Chinese could still find protection through the judicial Court. In 1889, by the Scott Act, the Supreme Court upheld immigration officials’ decision to reject the entry of a Chinese laborer who had a permit to return to the United States, denying his habeas corpus petition. In 1893, Chinese immigrants living in the United States were detained by law enforcement in New York City because they did not have the resident certificate requested by the Geary Act, and the Supreme Court found the detention lawful. In 1895, a Chinese businessman in San Francisco with documents and witnesses was denied entry and detained. The majority of the Supreme Court was in favor of the Government. In 1905, even an American-born Chinese citizen was denied the entry right, and the Supreme Court agreed to waive judicial review and allowed immigration officials to act arbitrarily.

Looking back, it was politicians who first rode the rising anti-Chinese waves to pass a series of Chinese exclusion laws. The Government formulated and implemented a series of regulations, gradually eroding the legitimate rights of the Chinese immigrants. The judiciary, represented by the Supreme Court, insisted on defending the Constitution and upholding justice before and in the early days after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, and later concede in the facing more systematic Chinese exclusion laws. The voices of justice were drowned out, and the Chinese lost their last support. Although there were still kind and fair American people everywhere who cared for Chinese individuals and offered assistance in many ways, the Chinese immigrant community entered unprecedented difficult years.

References

- Elizabeth Yuan, ’22 Lewd Chinese Women’ and Other Courtroom Dramas. A U.S. circuit judge brings historic Asian-American trials back to life, The Atlantic, September 4, 2013.

- Chinese Women Arrested: A Furore in Cklnadom in Reference to tlaa Matter, Daily Alta, August 26, 1874.

- Race, Racism and the Law, Accessed December 6,2022,https://www.racism.org/index.php/en/articles/citizenship-rights/immigration-race-and-racism/1506-marriage-and-morality?start=12

- Marriage and Morality: Examining the International Marriage Broker Regulation Act – A. Act to Prevent Kidnapping and Importation of Mongolian, Chinese, and Japanese Females, Accessed May 15, 2019, https://racism.org/articles/citizenship-rights/immigration-race-and-racism/1506-marriage-and-morality?start=12

- Paul A. Kramer, The Case of the 22 Lewd Chinese Women, a crazy 19th-century case shows how the Supreme Court should deal with Arizona’s immigration law. Slate, April 23, 2012.

- A Righteous Decision: Judge Morrison Orders the Chinese Courtesans to Be Taken Back to China, S.F. Chronicle, August 30, 1874.

- Kramer, 2012.

- The Burlingame-Seward Treaty, 1868. Office of the Historian, Department of State, Accessed May 12, 2019, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/burlingame-seward-treaty

- 14th Amendment Citizenship Rights, Equal Protection, Apportionment, Civil War Debt, Accessed May 19, 2019, https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/amendments/amendment-xiv

- Chy Lung v Freeman ET AL., Legal Information Institute, Cornell University, Accessed November 21, 2021, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/92/275

- Page Act of 1875,Accessed December 6, 2022,https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Page_Act_of_1875

- Angell Treaty of 1880, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://immigrationtounitedstates.org/343-angell-treaty-of-1880.html

- Scott Act, 1888, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott_Act_(1888)

- Geary Act, 1892, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geary_Act

- Chew Heong v U.S., 112 U.S. 536 (1884), U.S. Supreme Court, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/112/536/

- CHAE CHAN PING v. UNITED STATES, 130 U.S. 581 (1989), LII Legal Information Institute, Cornell University, Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/130/581

- Fong Yue Ting v U.S., 149 U.S. 698 (1893), Accessed November 28, 2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/149/698/

- The Constitution, the White House, Accessed November 28, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/our-government/the-constitution/

- U.S. Reports: Lem Moon Sing V U.S., 158 U.S.538 (1895), Library of Congress, Accessed November 21, 2022, https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep158538/

- Unites States v Ju Toy, 198 U.S. 253 (1905), Accessed November 28, 2022, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/198/253/