Zhida Song-James

I first learned about California Delta due to its importance in the State’s water resources system. During a conversation with a California-born colleague, he casually mentioned that once there were Chinese farms in the Delta.

Today, the Delta is one of California’s richest agricultural regions. Since the 1860s, Chinese immigrants were already settled in the delta and created Chinatowns in and between the two towns of Freeport in the north and Rio Vista in the south. Over one hundred fifty years, the history of Chinese immigrants in the California Delta is a history of their contribution to this land and the discrimination they suffered, a story of pioneering, resilience, and striving.

The Chinese immigrants who came to California in the late 19th and early 20th centuries faced many challenges and discrimination. Still, they made an irreplaceable and indelible contribution to the development and prosperity of the region.

Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta

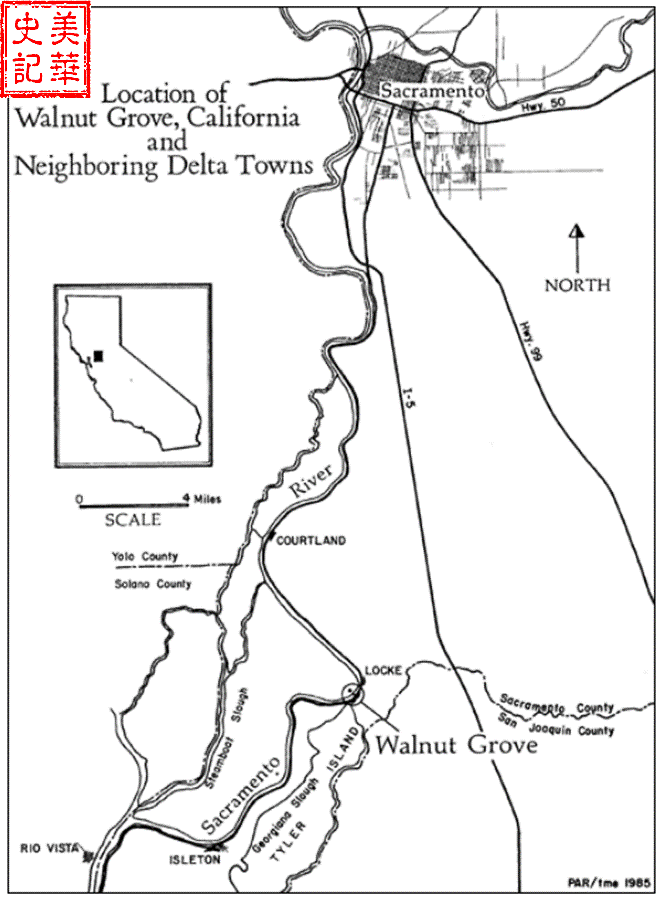

California Delta is a sprawling inland delta and estuary with a size of 1,100 square miles. It formed at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, therefore also called the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The Delta’s landscaping was a vast network of river channels and higher ground (islands) surrounded by marshes. Tidal water from the ocean and overflow from the river runoff periodically flood the expansive lowlands where the elevation is as low as five feet or less above sea level. The frequent inundations affected soil composition. Marsh plants like tules and reeds grew, died, and decomposed over more than 10,000 years to form an organic soil known as peat.

Picture 1, California Delta. Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Beginning of Reclamation

The consecutive federal Swamp and Overflow Lands Acts of 1849, 1850, and 1860 started the page of wetland reclamation in the United States. The Acts permitted the States to sell swamp land in the public domain and use the proceeds to finance internal land improvements, such as constructing levees and dredging drainages. In 1855, the California legislature authorized the sale of “swamp and overflow” lands in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta at $1 per acre, with 320 acres as the maximum per patch. This upper limit was doubled in 1859 to attract more settlers to convert the marshes to farmland. In 1859 the State removed the acreage limit to accelerate the reclamation. 1

Picture 2, Tule Marsh, the image created by Bing

The investors and land agents immediately grabbed the opportunity to purchase large tracts. One of the largest, Tide Land Reclamation Company, obtained 120,000 acres of Delta land in 1869. They aimed to buy cheaply, reclaim the land and sell for a high profit. The acquired land price was as low as $1.50 per acre; the reclaimed lands were sold at up to $75 per acre. The estimated profit was ample; however, the reclamation progressed slowly due to labor shortage until Chinese immigrants arrived. By 1871 Tide Land Reclamation Company’s holding jumped to 250,000 acres. 2

From Railroad Workers to Levee Builders

After the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, most Chinese workers were terminated by the Central Pacific Railroad and needed to find new jobs. Many workers were from the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong (formerly Canton) province. They had skills and experiences from the homeland, particularly fit to converting the swamps into farmland. The land in Delta was fertile, but it is also prone to flooding and erosion. Their first task is building levees to protect the higher islands from flooding.

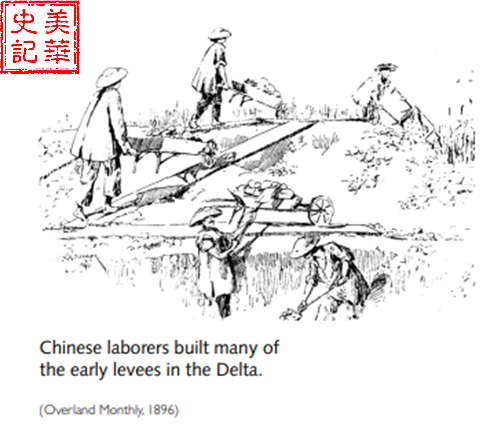

Picture 3, a California magazine, Overland Monthly, published an article in 1896 about Chinese workers building embankments in the Delta with the illustration on the left.

Chinese laborers worked under the contract system, as they did during the transcontinental Railroad construction. Chinese labor agents or “bosses” negotiated contracts with the land owners, employed laborers, organized and managed workforces, and paid wages. The bosses also provided food and board, usually just makeshift camps. Reclamation companies liked such a system as it simplified the process of hiring and managing many workers and consequently reduced competition and lowered costs.

The Chinese laborers built almost all the levees in the Tide Land Reclamation Company tracks. By 1876, as many as 3,000 Chinese laborers were employed in levee construction. It was before mechanical dredges were generally applied; the tools Chinese workers relayed on were shovels, wheelbarrows, wooden rammers, and baskets. They “dammed sloughs, cut drainage ditches, built floodgates, and piled up levees.” 3 The manually-constructed levees were impressive: they usually had an eight to twenty feet wide base, four to six feet high, and three to six feet wide at the crown. The circled embankment protected the entire island from flooding. 4 The Chinese workers also took time-consuming and painstaking work to drain the muddy water, clear dense aquatic plants, break the compacted soil, and level it into arable fields.

Their works were recognized by Tide Land Reclamation Company as well as others. Amid rising anti-Chinese sentiment in California cities and the clamor that “Chinese must go,” California state legislature set up a committee to investigate the status of Chinese immigrants. George D. Roberts, the Company’s principal investor, clearly told the committee that the Chinese were good workers; without their efforts, reclamation could be virtually impossible in the Delta. 5 In his 1876 report to the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Benjamin S. Brooks, a Republican congressman from California, admitted: “Chinamen reclaim these lands; they build levees; they patiently work in the mud and water where white men will not; and as a rule, it may be said they ‘create’ wealth for they do that work which but for them would not be done at all.” 6,7 The profits of the Tide Reclamation Company gained from Chinese laborers on the 40,000 acres of reclaimed land were estimated between $1,000,000 and $2,000,000. 8

Unfortunately, such testimony was erased from history for a long time.

The Chinese levee builders were essential for creating and preserving the farmland in the Delta. Between 1860 and 1880, they drained and reclaimed 88,000 acres of rich river-bottom peat soil — ideal for agriculture, and planted willows along the levee to prevent erosion. Levee builders not only paid for their sweat but their lives. In an unusually harsh winter of 1885, levees on several islands were washed away after recording rainfall. Flooding was particularly devastating on Robert’s Island. Four Chinese workers and a white engineer drowned when repairing the broken levee to save lives and property on the island.9

As more machinery was introduced, these manually built early levees were continuously strengthened, and some were rebuilt; drainages were dredged. By 1930, the levees protecting 55 Delta islands and the drainage systems were completed. Now all levees and other flood protection structures in the Delta are managed and maintained by the Sacramento District of the U.S. Army of Crops of Engineers (USACE).

Picture 4, The Sacramento Military District of USACE repairs the levees at Walnut Grove. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District.

Pioneers of Delta Agriculture

Chinese were not only levee builders. Many of them stayed in the Delta and became pioneers of delta farming and laid the foundation for the world-leading California agriculture.

By 1880, land reclamation shifted to more efficient and cheaper mechanical operations. New and stronger levees were built from clays and alluvial material dredged from the channels. The labor demand was dramatically reduced. Tenant farming emerged on newly created rich land. The Chinese immigrants, many originally farmers in their homeland, were very active in agriculture development. Most of them initially leased land; as the scale of agriculture expanded, many became agricultural workers.

Lee Phillips, a capitalist, saw the opportunity to invest in the reclaimed land; he formed California Delta Farm in 1906. The “Farm” was not interested in cultivating land; instead, its business was to lease the reclaimed land and turn it into tenant farms. 10 Many Chinese farmers leased land from such owners to grow various crops; the most famous were potatoes, celery, onions, and orchard crops. Chinese from Zhongshan County were specialized fruit orchards, and those from Si Yi (four former counties of Xinhui, Taishan, Kaiping, and Enping on the west side of the Pearl River of Guangdong Province) were vegetable growers. The reason for such a separation was that each region had its distinct dialect.

Asparagus later became one of the leading crops. When it was first introduced, eager-trying Chinese farmers actively participated in the field experiment on Bouldin Island to determine if asparagus could grow on the delta soil. In 1901 the Chamber of Commerce of Stockton, the major city on the San Joaquin River, praised Chinese farmers for their “expertise in horticulture” and (many) “members working in the field” as essential factors in successfully introducing this highly profitable new crop. When later factories were built to can asparagus, owners recognized that the Chinese workforces were the backbone of the industry’s success. 11

Picture 5. Chinatowns in Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Source: National Park Service.

Chinese Farmers were known for their hard work, efficiency, and innovation; some eventually developed large-scale tenant farming.

Chin Lung, who arrived in California in the 1880s, was among the first Chinese who leased land in the Delta. Starting from a small patch, he eventually expanded his leased land and hired as many as 500 Chinese laborers. He grew a variety of crops, most famously potatoes, as well as asparagus, beans, onions, and grain, and became one of the major producers of Delta. Delta-grown potatoes were particularly popular in the eastern market; he was known as the potato king for a time. Like other industries that relied on Chinese laborers in the same period, Chin adopted the same contractor system. He negotiated the lease with the land owner, hired Chinese laborers, provided boarding, appointed supervisors for the daily work, and developed his produce distribution system.

However, like all Chinese farmers, Chin faced many obstacles and challenges. They had to fight racism and exclusion from the “dominant society.” They were subject to discriminatory laws and regulations restricting their rights and stripping their opportunities.

After many years of cultivating his leased field, Chin purchased a large, 1,100-acre land in 1912 and planned to start his farm. Just a year later, the California legislature passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” i.e., Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and other Asian immigrants, from owning land. In 1920 updated Alien Land Law further prohibited “ineligible aliens” from leasing land in the name of their US-born children. From 1860 to 1920, ninety percent of the Delta had already been reclaimed; many Chinese immigrants, like Chin, had played crucial roles from the very beginning. They were not “sojourners”; Chin and many others worked hard to make this land their homes. However, they all were forced to leave California when their last land leases expired.12 Japanese farmers who moved to the Delta after the 1882 Chinese Exclusive Act suffered the same fate.

Despite these difficulties, the Chinese farmers persevered and survived. A few Delta Chinese persisted and stayed in the small river towns between Sacramento and Antioch. Locke was one of the few places where the Chinese escaped the notorious “driving out” when most Chinese farm workers, who made up 75% of California’s agricultural workers in 1890, were expelled.13

Locke was built on the land leased from George Locke, a pear grower. In 1912 three Chinese businessmen constructed a salon, a boarding house, and a gambling house which also served as the social center for the Chinese immigrants. California passed the Alien Land Act (Webb-Haney Act) in 1913, which jolted all Delta towns. In 1915, a fire burnt out the Chinese quarter of Walnut Grove (Picture 5). Chinese businessmen negotiated with Walnut Grove’s bank owner Alex Brown, who agreed to add seven more buildings in Locke instead of rebuilding in Walnut Grove. The new buildings included stores and a new gambling hall. Most Walnut Grove Chinese moved to the newly constructed Locke. At its peak, Locke’s permanent population reached around 400, and up to 1,000 seasonal workers entered the town and the nearby orchards during harvest and packing peaks. 14 The agriculture patterns Chinese immigrants started in Locke, including contracted labor, tenant farming, sharecropping, and the piece wage system, are continued today in the Sacramento-San Joaquin region and California,

In the harsh environment after the Chinese Exclusion Act, little Locke became a safe haven for the Chinese and a base for them to preserve their traditions. They grew Chinese vegetables such as snow peas, winter melon, and napa cabbage in their public garden, and families gathered to celebrate traditional Chinese holidays.

Picture 6, Visitors are paying respect in Locke’s Chinese Cemetery, photo by Cathy Huang.

After repealing the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, Locke’s Chinese gradually found other jobs and left the town, moving to cities or suburbs. Locke was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1990. The old houses and streets are maintained as their origin look, but few Chinese still live there.

Delta Today

What is the Delta like now? Can we still see any Chinese Farm relics? With these questions in mind, I went to the Delta.

Picture 7, Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta in California, USA, looking northwest. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/76074333@N00/6744795173/ by worldislandinfor.com

I entered Delta from the south. Antioch is located upstream of the confluence of the Sacramento and the San Joaquin Rivers. The city had a history of “driving out” Chinese immigrants who were already barred from walking on streets after sundown. On April 29, 1876, white mobs told Chinese residents that they had “until 3 p.m. to leave Antioch — no exceptions.” After they were forced to leave, the city’s Chinese quarter was burned. Some Chinese escaped to the Delta, drained swamps and built levees, grown vegetables and fruits to feed Californians, regardless of their colors.

In May 2021, the Antioch City Council unanimously adopted the resolution to formally apologize to early Chinese immigrants. “I think we will be the first city, not only in the Bay Area, in California but throughout the United States, to officially apologize for the misdeeds and mistreatment of the Chinese,” Mayor Lamar Thorpe said at the news conference.15

Driving north, I crossed the river channels to River Vista. It was early summer; roadside signs told me I had entered orchard land during its harvest season.

Figure 8. On California Delta Farm Trail, photo by Zhida Song-James

Northeast along the Sacramento River, I arrived in Isleton. When at its peak, Isleton’s Chinese population was about 1,500. Its Chinese quarter is reserved as a National Historic Landmark. Although few Chinese still lived there, a renovated Chinese community center/school building and a well-maintained Chinese-style pavilion stand as monuments, silently recording Chinese immigrants’ footsteps and reminding people of their contributions to Delta, California, and the United States.

There is no doubt that Chinese immigrants contributed to the economic and social development of the Delta region. They are an essential part of the history and heritage of California Delta. Their story is one of courage, resilience, and achievement. Their legacy is still widely visible today in the Delta region’s landscape, culture, and economy.

Picture 9 (Left), Chinese Labor Memorial Pavilion, Isleton. Each wooden sculpture on this octagonal pavilion records a piece of the history of Chinese immigrants in the United States. Photo by Zhida Song-James

Picture10 (Right), This building was constructed in 1926. It was purchased by the Bing Kong Tong (or Bing Gong Tang) and occupied by its Isleton branch. The lower floor was a Chinese language school where students came after their regular school time. The 2nd floor used to serve as the Chinese community center and was opened as Isleton Museum in 2022. Photo by Zhida Song-James

References:

- Daniel D. Arreola, The Chinese Roles in the Making of the Early Cultural Landscape of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 1975, P2. Accessed June 9, 2023. CAgeographer1975_p1-15.pdf (csun.edu)

- Alan M. Paterson, Rand F. Herbert and Stephen R. Wee, Historical Evaluation of the Delta Waterways, Final Report, Prepared for the State Lands Commission, 1978, P7.

- George Chu, Chinatowns in the Delta: The Chinese in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 1870–1960, California Historical Society Quarterly 49, 1970, no. 1, P24.

- Philip Garone, Managing the Garden: Agriculture, Reclamation, and Restoration in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California State University Sacramento Center for California Studies, Delta Narratives: Saving the Historical and Cultural Heritage of The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 2015, Garone P26.

- U.S. Congress Report of Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration, 44th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Report 689, 1877, P436-441.

- Benjamin S. Brooks, The Chinese in California, Report Delivered to the Committee on Foreign Relations of the U.S. Senate, San Francisco, 1876, no page number.

- Arreola, 1975, P3.

- Jennifer Helzer, Building Communities – Economics & Ethnicity, California State University Sacramento Center for California Studies, Delta Narratives: Saving the Historical and Cultural Heritage of The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 2015, Helzer P19.

- Sylvia Sun Minnick, Samfow: The San Joaquin Chinese Legacy. (Panorama West Publishing), 1988, P156.

- Philip Garone, 2015, Garone P43.

- Minnick, 1988, P183-184.

- Garone, 2015, P42-43.

- Carmen Lee, California Agriculture’s Chinese Roots, Vegetarian News, Fall Issue, 2008.

- William R. Swagerty and Reuben W. Smith, Stitching a River Culture: Communication, Trade and Transportation to 1960, California State University Sacramento Center for California Studies, Delta Narratives: Saving the Historical and Cultural Heritage of The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 2015, Swagerty & Smith, P51.

- CNN, May 21, 2021.