Author: Xin Su

Translator: Pingbo Zhou

ABSTRACT

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first and only law in US, implemented to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the United States. It was signed on May 6, 1882 and repealed on December 17, 1943. The declining economy and high unemployment were politicized for the anti-Chinese movement by Denis Kearney, a labor leader who was himself an immigrant from Ireland. When the Sand Lot rally erupted in San Francisco in 1877, Kearney helped found the Workingmen’s Party of California with a sledgehammer four-word slogan: “The Chinese must go!” Kearney’s attacks against the Chinese for working for cheaper wages were supported by many white Californians. The Workingmen’s Party won almost every elective seat in San Francisco and successfully promoted anti-Chinese sentiment. By 1882 the federal government was finally convinced to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning all Chinese immigrant laborers. The Workingmen’s Party of California was gone after the passage of The Chinese Exclusion Act.

~~~~

Leaders often have their own slogans and catchphrases. Who did the phrase “The Chinese Must Go!” belong to?

Leaders play a decisive role in key historical moments and can either change the course of history for the better or the worse. It is up to us in the present to reflect on and evaluate the merit or fault of their actions.

Denis Kearney’s Workingmen’s Party of California was around for less than five years, an insignificant amount of time in the context of human history. The reason it is important is the countless ripples and after-effects that it led to, some of which are even repeating in the present day…

The national economic recession from 1873 to 1878 and San Francisco’s Sand Lot riot had momentous impacts on that period of American history. The Workingmen’s Party of California rode this historical tide and was founded in 1877. In 1878, it had taken control of the California legislature and revised the state constitution[1].

Kearney and other labor leaders relied on racist rhetoric to alienate Chinese immigrants. They described the Chinese as “cheap wage slaves”, the lowliest, basest, and most obedient slaves. They claimed that the Chinese had lowered the American quality of life, and therefore must be evicted from the country.

A laborer’s highest priority is meeting his survival needs, not his intellectual or moral ones. Kearney’s openly racist attacks against the Chinese won him widespread support. Amidst a sea of racist mainstream voices, the Chinese were hopeless to defend themselves and fight for their rights. Kearney was successful in promoting anti-Chinese sentiment, which ultimately culminated in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

Although Kearney was not the sole force behind the Chinese Exclusion Act, he remains a vital part of the conversation when it comes to America’s anti-Chinese history.

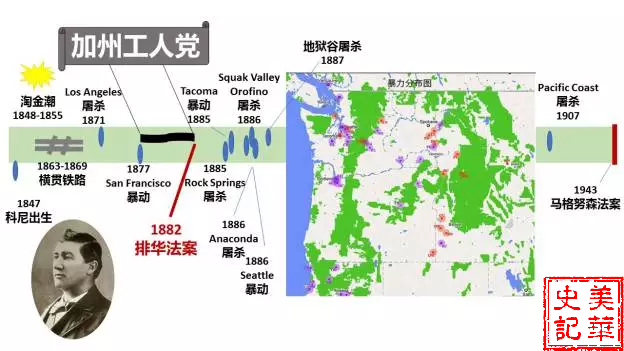

Image 1: Kearney’s Workingmen’s Party of California promoted and led America’s anti-Chinese movement from 1877-1882.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, which was in place between 1882 and 1943, forced the Chinese to the bottom layer of American society. Along with the rise of the Chinese Exclusion Act, violent acts towards the Chinese became widespread, especially in the Pacific Northwest region. The image of Kearney is sourced from [2], and the “Map of Violence Against the Chinese” comes from the geographical breakdown of violent acts against the Chinese in the Pacific Northwest presented by http://www.cinarc.org/.

Part One: The Anger Towards Chinese Laborers

Poverty and unemployment will always contribute to panic and unrest, and panic was heavy in the air in sunny California.

Many white workers lost their jobs, yet the Chinese did not lose theirs, continuing to provide large amounts of cheap labor to American society. The stiff competition discouraged white workers; unfortunately, the Chinese were scapegoated as the root of their problems.

Along with the California Gold Rush in the 19th century, large amounts of Chinese migrants came to America. In 1852 alone, 20,026 Chinese immigrated to California. When the American economy experienced a downturn in 1853 and 1854, railroad construction halted and gold prices fell, and anti-Chinese sentiment and anger became more prolific. Conflicts became more and more violent [3].

In reality, the Chinese were doing hard jobs that many whites refused to do, such as plowing the fields, running laundries and restaurants, and serving as domestic workers. Of course, even these jobs were too much for them in the eyes of unemployed white workers, who believed that the Chinese had taken jobs that should have belonged to them.

These whites felt humiliated by the foreign Chinese workers. They believed themselves to be racially superior and could not endure working alongside the Chinese in a time of high unemployment. To these white workers, who had become American citizens after coming to the U.S. from Europe, working with the Chinese was an unbearable disgrace.

As a result, a series of laws were passed to constrain Chinese migrants. In 1852 the passage of a foreign miners’ tax imposed a three-dollar monthly tax on foreign miners in the state. In 1855, the California legislature passed another act entitled Discourage the Immigration to this State of Persons who Became Citizens thereof. On February 19, 1862, the 37th United States Congress passed An Act to Prohibit the “Coolie Trade” by American Citizens in American Vessels, thus reducing the number of Chinese laborers in the country and protecting white laborers.

Eight years after the anti-coolie law of 1862, the Naturalization Act of 1870 allowed African Americans to become American citizens through naturalization, expanding the citizenship rights of African Americans. However, it continued to exclude Asians and prevent the Chinese from becoming naturalized citizens. Chinese immigrants were barred from voting or serving on juries, and dozens of states passed alien land laws preventing non-citizens from buying real estate. This made it so the Chinese could not establish permanent housing or businesses[4].

List of Notable Laws and Declarations Regarding the Chinese[5]:

- 1850: California passed the Foreign Miner’s Tax, which was renewed in 1852, 1853, and 1855. Although it did not explicitly spell out a race, it was clearly designated to target Chinese miners and mining zones.

- 1852: California Immigrant Bonding Law required all Chinese arriving in California to pay a $500 bond.

- 1852: The Foreign Miner’s Tax rose from $3 to $4. Many mining zones prevented the Chinese from prospecting.

- 1854: The California Supreme Court prohibited the Chinese from testifying against whites.

- 1855: Several California counties required a $50 “citizenship tax” per person ineligible for citizenship, an act designed to target the Chinese.

- 1855: Required a $50 capitation tax per Chinese immigrant.

- 1858: California passes a “law” restricting immigration of Chinese and Mongolians.

- 1860: Public schools in northern California stop accepting Chinese children. In 1866, a law was passed stating that Chinese children could only attend white schools if white parents did not object.

- 1860: San Francisco passes a law stating its hospitals are not open to Chinese patients.

- 1868: The Burlingame Treaty was positive legislation for the Chinese, granting right of reciprocity for voluntary immigrants.

- 1870: San Francisco public works projects prohibit the hiring of Chinese workers, and the city bans the use of shoulder poles to transport vegetables.

- 1870: California allows immigration officials to decide at will whether or not immigrant women are prostitutes in the Act to Prevent Kidnapping and Importation of Mongolian, Chinese, and Japanese Females.

- 1870: California requires Chinese men to show proof of good character before below allowed to immigrate.

- 1870: California prohibits any Chinese from owning land.

- 1873: San Francisco mandates that laundries transporting goods via shoulder pole must pay a $15 tax per season, while those using carriages only have to pay $2.

- 1873-1875: San Francisco passes a series of laws prohibiting firecrackers and gongs.

- 1875: San Francisco passes an anti-queue act; those who refused to cut their hair would be jailed.

- 1875: San Francisco law requires living spaces to have at least 500 square feet of space, to prevent poor Chinese people from crowding into small apartments.

- 1875: California passes law governing the size of shrimp nets, thus visibly decreasing the catch of Chinese fishermen.

- 1875: The Page Act prevents prostitutes and those with mental illness from entering the country. Although this law did not directly target the Chinese, it set a legal precedent through which they were alienated.

- 1876: Henderson v. Mayor of New York rules that the federal government has absolute say over immigration law. This effectively rendered all other laws surrounding Chinese immigration unconstitutional.

- 1879: California law prohibits businesses and municipalities from hiring the Chinese, and forced the Chinese to live in designated areas on the outskirts of the city.

- 1879: U.S. Congress passes law limiting the number of Chinese migrants that can be brought to America per vessel to 15.

- 1880: San Francisco anti-ironing law prohibits nighttime operations of laundries.

- 1880: California passes a fishing law that prevents the Chinese from working in the fishing industry.

- 1880: The Angell Treaty, which proposed to ban Chinese migrant workers from coming to America, passes a review.

- 1882 San Francisco laundry registration law requires Chinese laundries to receive a permit.

- 1882: California declares that anti-Chinese demonstrations will be treated as public holidays.

- 1882: Chinese Exclusion Act is passed.

Over time, whites grew increasingly angry and vengeful towards the Chinese, and racial conflicts happened regularly. In 1871, one of the most severe acts of anti-Chinese violence occurred in Los Angeles, and 17-20 Chinese were lynched in a brutal night[6].

The justification for alienating Asians was that Asians could not be integrated into American society. The notion that Asians and Chinese were an “undesired” race was the basis for Chinese exclusion. Twelve years later, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, directly prohibiting Chinese immigration and naturalization [3,4,7,8].

Part Two: The Beginning of Kearney’s Anti-Chinese Political Movement

From 1873 onwards, severe economic crisis befell the United States, which had been weakening for some time. With the decline of economic opportunities on the East Coast, many people (approximately 150,000) headed west. The unemployment rate on the West Coast skyrocketed and caused mass dissatisfaction. Most of the Chinese in San Francisco lived in Chinatown; the tense racial situation in the city directly contributed to the numerous instances of violence that occurred throughout Chinatown.

In 1877, from the evening of July 23 to the evening of July 24, there were large-scale violence and riots against the Chinese led by whites.

This riot seemed spontaneous, but was ultimately inevitable. On the night of the 23rd, members of the Workingmen’s Party held a special session debating the needs of workers, especially those who had lost their jobs. Roughly 8,000 people swarmed into the San Francisco city center. There had actually been rumors that people wanted to destroy a pier where the Pacific Mail Steamship Company handled Chinese immigration services. However, city officials did not try to stop the congregation, and the July 23rd meeting was held as scheduled.

Representatives of the Workingmen’s Party engaged in lengthy discussion on the questions and subjects raised by the laborers, blaming the Chinese for the unemployment that many of them were facing and riling up the audience. Anger and desperation spread like wildfire among the attendees, and the crowd’s cheers and shouts gradually turned violent…

At this time, a group outside the crowd began attacking a Chinese person, and began shouting “To Chinatown!” A surge of angry rioters rushed towards Chinatown and engaged in two days of violent rioting. The chaos led to four deaths, twenty Chinese-owned laundries were destroyed, and over $100,000 in damages [9].

On the night of July 24th, after efforts from local police, the state militia, and up to a thousand members of the citizen’s vigilance committee, the racial conflict was finally halted. Kearney gained recognition due to his efforts in calming down this riot, which kickstarted his short yet impactful political career.

Part Three: The Rise of Kearney

It would not be an exaggeration to say that history is written by political leaders, since every major social event has deep ties to a leader or agitator.

Kearney was born in Oakmont, County Cork, Ireland in 1847, and died in Alameda, California in 1907. His birth and death were both unextraordinary. It could be said that prior to 1877 he was a nobody, and faded from the public eye after 1882. The only memorable period in his life was the five years between 1877 and 1882, when he initiated and led America’s anti-Chinese movement [3, 5].

As a result of the Irish Potato Famine, boys in Irish families left home early to fend for themselves. Kearney was the second of seven sons in his family, and his father died when he was young. At age 11, and without any schooling or education, he went to work on ships for a living. In 1868, he arrived in America, and married an Irish woman who gave birth to a son and two daughters. He and his family lived in San Francisco and worked in the transport business. His business did well, and by 1877 he owned five wagons.

Quickly, Kearney rose among the masses, becoming the spokesperson and labor leader for the Workingmen’s Party of California. In October 1877, San Francisco’s labor organization was reconfigured into the Workingmen’s Party of California and Kearney became its leader. He united the poor and working classes in opposition of the industrialists, especially the greed of the railroad companies. He came an extremist due to his nativist beliefs and his racist hatred towards Chinese immigrants. His anti-Chinese slogan was “The Chinese must go!” [3, 5].

It is important to note: the Workingmen’s Party of California was a party for laborers that Kearney led in the 1870s, and should not be confused with the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, which was based on the East Coast and had relatively limited influence.

Although Kearney had never gone to school, he was an avid reader and a self-taught learner. He enjoyed debate and had a sharp wit, often going off on long speeches that smeared the media, capitalists, politicians, and the Chinese. He understood what words and phrases could create strong emotional responses in his audiences and lead them to take action. This can be seen in the speeches and articles he prepared.

Kearney was an extremely influential leader. In his early speeches, he called on laborers to be “thrifty and industrious like the Chinese”, but within a year, he was blaming Chinese laborers for the economic crisis that white workers were facing. In 1878, he frequently denigrated the Chinese and the problems they created at the Sand Lot. That year, Kearney also went to Boston and spread anti-Chinese sentiment on the East Coast. He received a warm welcome, and attracted audiences in the tens of thousands.

He warned the railroad companies that they had three months to fire all Chinese laborers. If the condition of white laborers had not improved, he said “If the ballot fails, we are ready to use the bullet”, and threatened to blow up the entire city.

Kearney definitely created a period of chaos and unrest. When he grew passionate in his speeches, he would throw away his coat and unbutton his shirt to roars and applause from his audience. He would then conclude his speeches with “The Chinese must go!”

Kearney and members of his party were arrested more than once, but were always quickly released because of a lack of evidence. These arrests and releases actually made him more popular among his rabid fanbase and expanded the influence of the Workingmen’s Party of California.

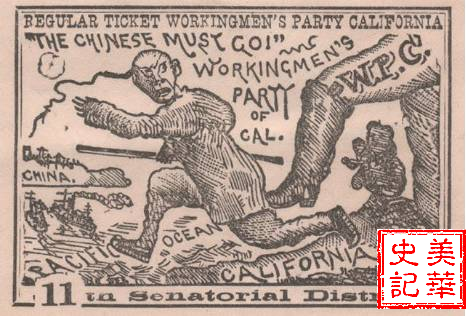

Image 2: Poster from the Workingmen’s Party of California. Image sourced from the California Historical Society.

The Workingmen’s Party of California quickly became California’s leading political force, displacing the Democrat Party as the Republican Party’s main contender. The Party won the election, and voted to rewrite the state constitution with more than a 33% advantage over the opposition [10].

Part Four: Canceling the Burlingame Treaty and Passing Chinese Exclusion

Clearly, Kearney could not pass laws on his own. Yet he undoubtedly contributed to an anti-Chinese environment in politics.

Kearney encouraged rewriting the California state constitution, formed a committee to investigate the “Chinese question”, and drafted anti-Chinese clauses into the proposed constitution. The committee recommended banning all Chinese immigrants from coming to America, preventing the Chinese from holding public office, and limiting the business licenses and property that the Chinese were eligible to obtain, among other suggestions.

Since the Chinese were blamed for the economic woes the country was facing, legislative bodies could use their power to prevent the Chinese from immigrating and settling in America. The final regulations prohibited the Chinese from working in companies or for the government, and took away their right to vote. It also gave local jurisdictions the power to deport or isolate the Chinese. Several extreme laws and protocols, including the ban on hiring Chinese laborers, were found unconstitutional by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Nevertheless, the ultimate legislation was still extremely anti-Chinese.

One of the Workingmen’s Party of California’s major efforts was to push for an overhaul of the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. This treaty was a friendly treaty between China and United States that granted China the status of “most favored nation”. It was signed in 1868 to expand upon the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin due to the efforts of Anson Burlingame, a diplomat who served as U.S. minister to China and later as China’s envoy to the U.S. The Treaty stated that citizens of both nations could freely immigrate or engage in trade. The Burlingame Treaty effectively protected the Chinese from being discriminated against or harmed via physical violence.

It is clear that the high number of Chinese laborers played a significant role in the construction of the continental railroad. By the same logic, in the mid to late 1870s, railroad construction had completed, and America had entered an economic recession, creating a surplus of Chinese workers. In reality, opposition voices calling for Congress to pass laws limiting or prohibiting immigration had begun in the 1860s. Kearney’s success was due to the fact that he managed to convey these ideas to lawmakers, such as James Blaine, Congressman and presidential candidate. Blaine said that their duty was to American interests, not the welfare of the Chinese.

Finally, the Angell Treaty was signed in 1880. This provided the legal basis for American officials to review whether immigrant Chinese laborers affected or threatened American interests and security. Although the Angell Treaty did not outright outlaw Chinese immigration, it was a clear departure from the spirit of the Burlingame Treaty, which allowed for unrestricted immigration between both countries. Kearney’s insistence that the “Chinese question” was a national problem led to the eventual Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

1882 was election year in California. In order to win more votes, California politicians eagerly affirmed their strong anti-Chinese beliefs. California Republican candidate John Miller stated that Eastern and Western cultures were incompatible, and that the Chinese would perpetually be foreigners and should not be allowed to immigrate to America[11]. All Western and most Southern Democrats supported Miller’s proposal, strongly opposing the point of view held by Eastern representatives. After intense debate, the House passed the Act with a vote of 202-37, with 52 abstentions, on April 17, 1882. On April 28, 1882, Chinese exclusion also passed the Senate with a vote of 32-17, with 29 abstentions. On May 6, 1882, President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law[12].

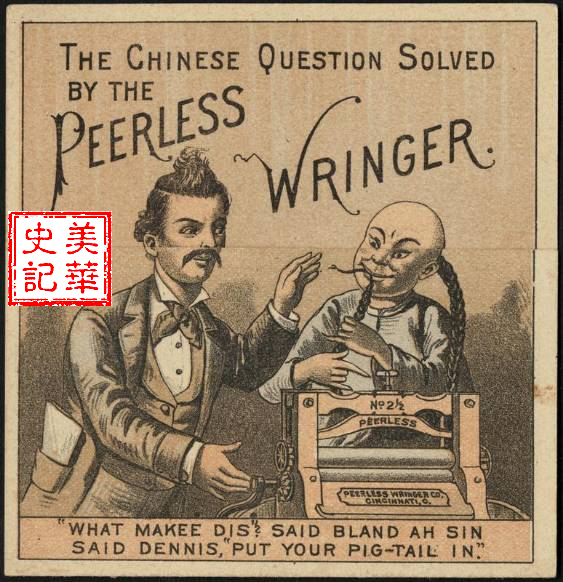

Image 3: The Chinese Exclusion Act claims to have solved the difficult “Chinese question”. Image sourced via Digital Commonwealth.

Part Five: Opposition Voices

Many people did not like Kearney’s rhetoric, his tendency to promote violence, and anti-Chinese attitudes. During Kearney’s visit to Boston to win the support of the East Coast working class, he received support from a few people but also no shortage of criticism. The Boston Transcript labeled Kearney as “a blatant booby”, and the Chicago Democrat called him “a flatulent little brat”. Some working-class observers also questioned Kearney’s motives, because they thought his language was “rooted in discrimination and not reason”[5].

In the social commentary section of the 1878 Labor Standard, Irish-born socialist Joseph McDonnell reminded readers that nearly every immigrant group that arrived in America had endured alienation and discrimination and been subjected to the same shameless and stupid cries to “go home!”[13] Hubert Bancroft, one of the most influential authors in California in the late 1880s, mocked the Workingmen’s Party as “ignorant Irish”. Former California attorney general Frank Pixley pointed out: these immigrants had just been graciously welcomed by America, yet they immediately turn around and flout the law by harassing another group of people who have the same legal rights as themselves. This behavior is extremely despicable![2]

The Workingmen’s Party of California’s victory was actually a victory for white supremacy and racism. This victory was brought about by sacrificing Chinese interests.

Part Six: Conclusion

Throughout their history, hard work and perseverance have been virtues that Chinese people cherish. No matter how much we have been discriminated against, we have fought for survival and upward mobility by taking on the hardest, dirtiest, and most undesirable jobs that others would not.

California governor Jimmy Doug praised the Chinese as California’s most valuable immigrants in 1852. Yet 30 years later, the “most valuable immigrants” were barred amidst shouts of “the Chinese must go!”

Our nation’s history of fearing immigrants is in the process of repeating, and anti-immigrant voices are rising again. The Native Americans fought against the Irish, British, and German immigrants from Europe; those European immigrants then excluded the Chinese. The older generation of immigrants always fears the new wave of immigrants, because their cheap labor provides extreme competition in the labor market.

History was once the present for those in the past. It is the result of generations of decisions, actions, and reflections!

References:

1. Cross, Ira. “Denis Kearney Organizes the Workingmen”. West Valley College.

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denis_Kearney

3. https://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/history/1870/anticoolieact.htm

4. “An Evidentiary Timeline on the History of Sacramento’s Chinatown: 1882 – American Sinophobia, The Chinese Exclusion Act and “The Driving Out””. Friends of the Yee Fow Museum, Sacramento, California. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

5. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. John Soennichsen. Landmarks of the American Mosaic Santa Barbara, CA:Greenwood, 2011.

6.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_massacre_of_1871

7. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Chinese_sentiment_in_the_United_States

8. Chin, Gabriel J. “Harlan, Chinese and Chinese Americans”. University of Dayton Law School.

9.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_riot_of_1877

10.http://immigrants.harpweek.com/ChineseAmericans/2KeyIssues/DenisKearneyCalifAnti.htm The Chinese Experience. HarpWeek, LLC. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

11,http://pluralism.org/document/1882-Chinese-exclusion-act-congressional-debate-senator-John-Franklin-Miller-of-California/

12,https://www.govtrack.us

13. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/