Author: Xin Su

Translator: Pingbo Zhou

ABSTRACT

Faced with continued prejudice at the turn of the 20th century, Chinese Americans had developed their own social organizations. However, the political struggle and corruption in American society had arguably made Chinatown to be a place filled with vices, violence, and bloody battles, which aggravated the plight of the Chinese whose life had deteriorated since the Chinese Exclusion Act. This kind of situation had not seen any improvement until 1921 and after 1931 it finally disappeared.

~~~

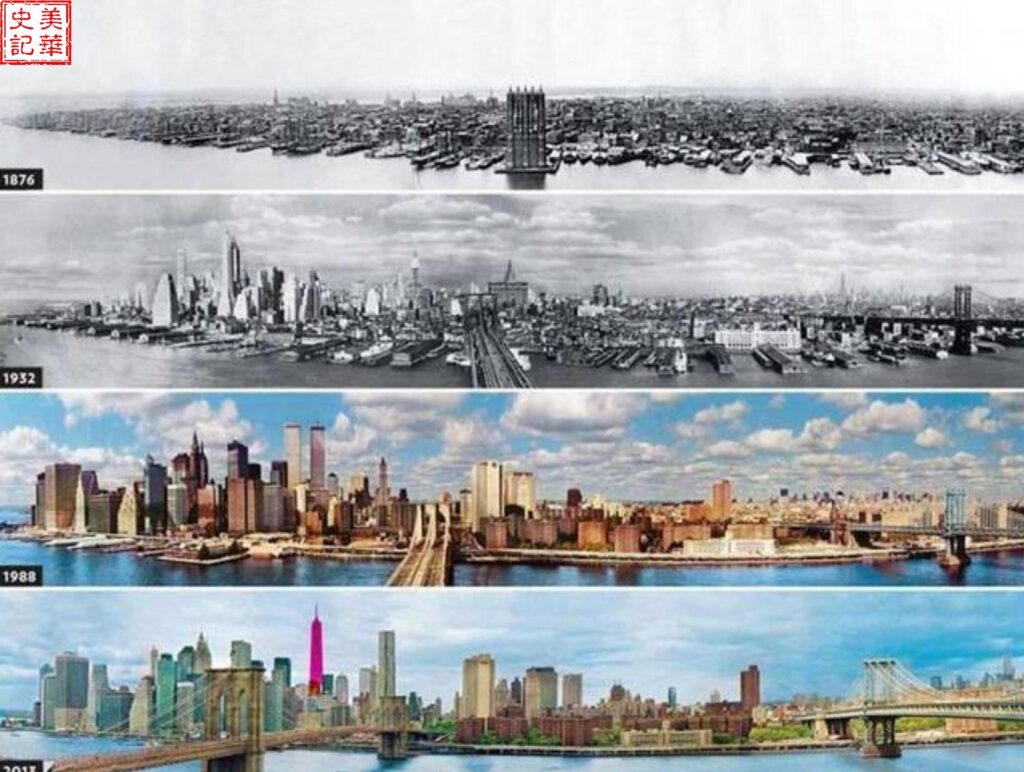

Finance, art, fashion, trends, skyscrapers, the Statue of Liberty, paradise for the adventurous… New York dominates in every aspect and its growth has been unrivaled. From 1870 to 1900, New York’s population nearly tripled to 3.5 million people. The city became the second largest in the world after London, and was the cultural capitol of the world (1, 2). Prosperity and poverty coexisted in New York at the time, and regardless of social status, the Irish, Italians, and Chinese came to the city in search of opportunity.

Image 1: New York’s evolution over time. Source: https://untappedcities.com/2014/03/21/downtown-manhattan-skyline-from-1876-to-2013/

Image 2: Manhattan’s Mulberry Street, also known as Little Italy, at the turn of the 20th century. Source: https://seanmunger.com/2015/01/29/historic-photo-mulberry-street-new-york-city-little-italy-1900/

Friendship: Friendship and companionship are everything – more important than government, more concrete than values, and closely tied to one’s personal safety and interests. The Chinese built a wall of friendship to create a highly isolated and self-sufficient Chinatown.

When new immigrants from China arrived in Manhattan, many were greeted at the train station or wharf by an enthusiastic businessman who was born in Hong Kong. He was short and stout (5’4”) and had sallow skin and an unshaven beard. His name was Wong ah Chung (1849-?), and everyone called him Wo Kee. In 1873, at just 24 years old, Wong opened a small store on 34 Mott Street called Wo Kee. Aside from providing amenities for newly arrived immigrants, he also sold cigars. In addition, he also operated an underground casino. New immigrants stayed at his home while they got their bearings, sleeping two to a bed. His home could accommodate up to 24 people(3). Over the years, Wo Kee helped many Chinese get settled in Manhattan and slowly formed a Chinese community. Wo Kee was the leader of this small Chinese community and formed a non-profit organization (called Polong Congsee) that had 75 members and several thousand dollars of funds. This organization helped Chinese immigrants get into the laundry business and look for jobs.

Accompanying New York’s growth and development, Manhattan’s Chinese population grew larger and larger. In 1870, there were possibly less than 100 Chinese in New York City; the 1875 census indicated that there were 157 Chinese in New York City. In 1880, the population increased to 4,500, and by 1890 there were approximately 13,000 Chinese in the city(3). The majority of the Chinese worked in the laundry business, where an enterprising worker could earn 10-14 dollars a week. It only cost $75 to open a laundry, and there was no competition with white workers in this industry, thus making it relatively easy for the Chinese to get into. There were also Chinese who worked in tobacco factories where they could earn $27 a week(4).

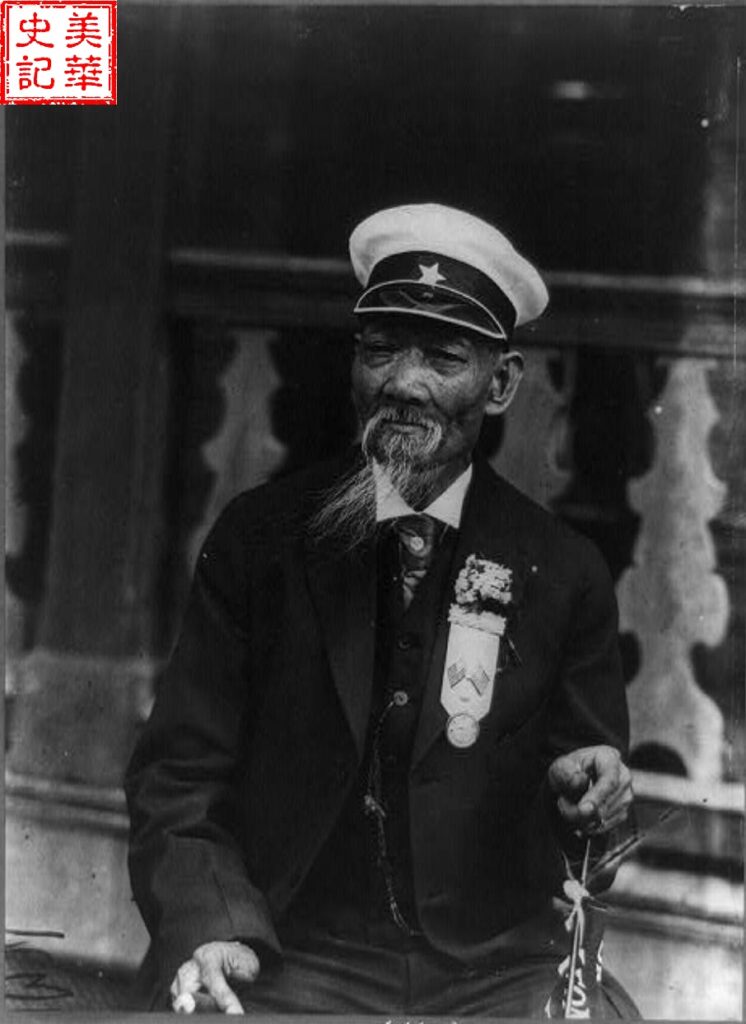

Around this time, a historic figure with a long, goat-like beard appeared among the crowd. Tom Lee, born Wu Ah Ling (5’6”), was short and skinny, but had a heroic air about him. In 1849, the 14-year old Tom Lee came to San Francisco from Guangzhou, China to work as a laborer in a white-owned company. He quickly became an influential figure in the local Chinese community. In 1876, Tom Lee was dispatched from San Francisco by the Six Companies. He traveled through St. Louis and Philadelphia and arrived in New York in 1878 (3,5).

Tom Lee was sharp and spoke in fluent, slightly accented English. He married an American woman. Upon arriving in New York, he and his wife rented a place on 20 Mott Street. This three-story brick building was luxuriously decorated and demonstrated his wealth and influence. Before long, Tom Lee began maneuvering politically, forming relationships with high-ranking white officials and inviting the most powerful figures in the legal and political sphere to parties at his home. As a result, he quickly became the leader and spokesman of Chinatown. In November 1878, he was lauded as a model citizen among the Chinese by New York’s The Sun Newspaper. It must be noted that at the time there were only a few Chinese in the city that were American citizens.

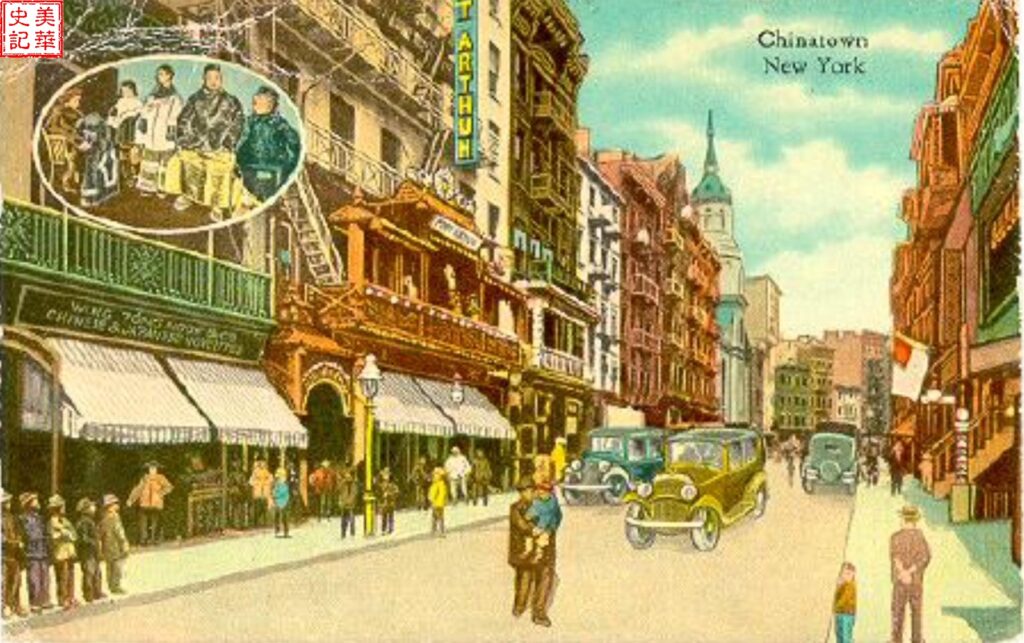

Due to their work ethic and business acumen, Chinese immigrants gradually established themselves. By 1879, New York City’s Chinatown had over 300 Chinese-run laundries, 50 vegetable markets, 20 tobacco stores, 10 pharmacies, and six Chinese restaurants. In the early 1880s, the Chinese owned practically every building on Mott Street, which became known as “Little China”(4).

New York was full of opportunities, but it was no paradise. Even the Chinese who were financially successful and had decent lives faced more and more discrimination. Most of them had limited English-speaking ability, and the police naturally could not speak to them in Chinese. This was especially problematic for casino owners, who desperately needed police protection. The Chinese were accustomed to authoritarian hierarchies, and Tom Lee became an arbiter between the Chinese and local officials. He collected fees from the Chinese in order to bribe cops and city officials for protection(7).

Image 3: Tom Lee (1849-1918). Source: https://blogs.baruch.cuny.edu/asianamericanhistorynyc/?p=446

Tom Lee succeeded Wo Kee as the leader among the Chinese and formed a new benevolent association called Loon Ye Tong in early 1880. The benevolent association collected $10 of initiation fees per member and $5 of annual membership fees per year. Within a few days, 150 people signed up and the association had collected thousands of dollars within a month. After a year, membership doubled to roughly 300 people(7).

Wo Kee became a friend and follower of Tom Lee.

Power: Power is the ability to realize one’s goals at any time, and to have the capacity to maintain influence or control actions both inside and outside the Chinese community even in the face of discrimination and Chinese exclusion. In Chinatown, Tom Lee had this kind of power.

Chinese social organizations (familial associations, business groups, mutual aid associations, and tongs) originally formed to protect Chinese interests and aid in everyday life by providing mutual aid, helping new immigrants navigate problems, and resolving disputes in an organized manner, among others. Tongs, which were similar to gangs, were an unofficial government structure in Chinatown that allowed the Chinese to implement a form of self-government. Tongs were also the bridge between the Chinese and the U.S. government; as a result, tong leaders were known as the “mayors” of Chinatown.

Loon Ye Tong quickly took over 18 Mott Street. Two-thirds of its members were laundry workers, so Loon Ye Tong was especially careful to protect the interests of the laundry industry. For instance, they set a rule that any new laundry had to be opened at least two blocks away, in order to protect the business of Loon Ye Tong members(5).

Tom Lee cleverly formed close relationships with Tammany Hall. Tammany Hall was a political organization associated with the Democratic party and its members were predominantly Irish Catholics. Starting in 1854, Tammany Hall began controlling the selection of Democratic candidates in Manhattan and had massive political influence for the next several decades. It was a major player in local politics, especially among immigrant communities(8). With Tammany Hall’s support, Tom Lee was elected as Manhattan’s deputy sheriff in 1880, becoming the first New York government official of Chinese heritage in history. This further cemented his absolute power in Chinatown (5, 9).

As Chinatown grew and developed, its major leaders flourished financially. Tom Lee’s personal wealth grew astronomically, and his net worth totaled $200,000 by 1883. At the same time, Wo Kee also had $150,000 in net worth. In April 1883, Wo Kee paid $8,500 for 8 Mott Street, another Chinese bought 10 Mott Street for the same sum, and yet another Chinese bought 15 Mott Street for $5,000. Tom Lee bought the most expensive unit, 18 Mott Street, for $14,500(10).

Image 4: 18 Mott Street, one of the earliest gambling dens. Source: http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2011/09/manhattans-chinatown-tribute-to-old.html

Of the 9,000 Chinese in New York at the time, only 50 were American citizens and had voting rights. Tom Lee was the undisputed leader of these 50 voters(10). His genius lay in his proficiency at bribing officials and securing his interests across a variety of departments. Although Tom Lee was investigated for collecting casino protection fees, which caused internal divisions in Chinatown, he was ultimately able to weather the storm due to his connections with politicians(10).

In 1886, Tom Lee formed a Chinese gambling association at 18 Mott Street with the primary purpose of controlling the gambling business and resolving internal disputes. If members were arrested, the association would help them get out of jail and receive protection from police and officials through bribes(11). As a result, city officials and representatives of various levels received shocking amounts of protection fees. This was Chinatown’s government, whose power and influence rivaled that of the official government. Tom Lee established a regular payment schedule for these bribes, which provided officials a stable “income”.

Tom Lee greatly valued his growing social prestige that came about as a result of his wealth and power. He was a passionate philanthropist and funded many events held in Chinatown. In 1889, China’s Yellow River overflowed and caused mass catastrophe in Shandong province. Tom Lee organized a donation of over $1,200 to flood victims, and donated the most out of those who participated. In addition, when Johnstown, Pennsylvania flooded in the same area, he spread the word and encouraged the Chinese to provide donations(12).

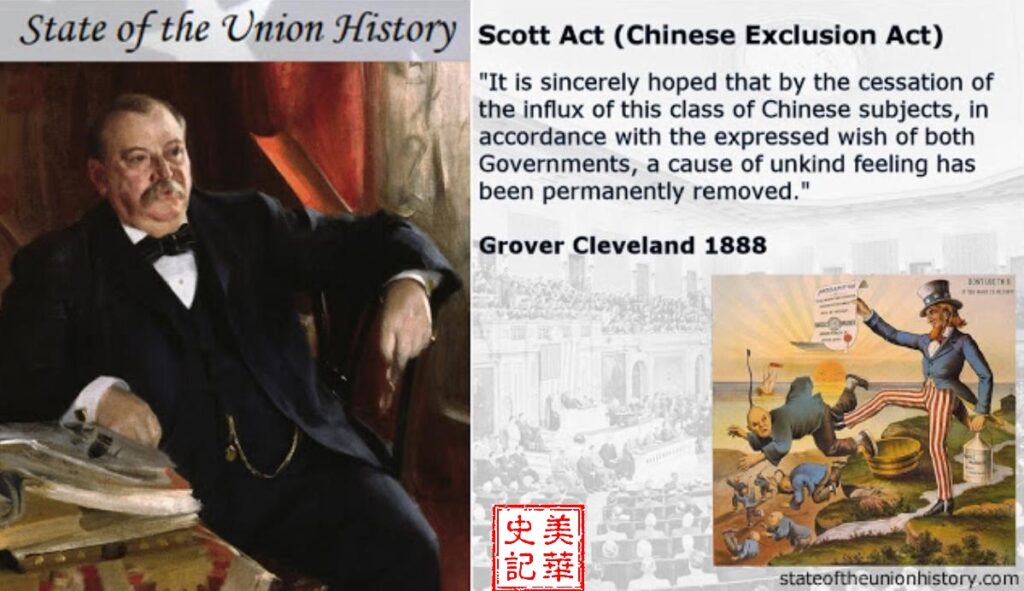

Image 5: Grover Cleveland signed the Scott Act, which permanently banned immigrant Chinese laborers from returning to the United States. Source: http://www.stateoftheunionhistory.com/2015/07/1888-grover-cleveland-scott-act-banning.html

Tom Lee continued to fight for the Chinese politically. On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited the immigration of all Chinese laborers and jailed or deported anyone who resisted. In addition, this law also stated that Chinese immigrants could not become naturalized citizens(13). On October 1, 1888, Democrat President Grover Cleveland signed the Scott Act, which prevented Chinese laborers from re-entering the United States after leaving the country(14). Cleveland was elected President again, beating out General Benjamin Harrison, who opposed Chinese exclusion. Tom Lee believed Harrison could potentially repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act, and provided him his full support in his bid for the presidency. Tom Lee and his followers put election donation boxes in front of Chinese restaurants and laundries. He personally donated $10,000 and called on wealthy merchants to donate as well. Tom Lee personally delivered the collected funds to Republican Party headquarters on Fifth Avenue. Despite this he also maintained close relationships with the Democratic Party(12).

Tom Lee successfully navigated political structures both within Chinatown and mainstream American society. His service and abilities made him respected in both underground and official circles, and made him the most powerful Chinese in New York at the time(12).

Wealth: Wealth is the food on our plates, the clothes we wear, the cash we carry, an essential for living, and the influence we have at our disposal. When people refuse to engage in honest labor, they resort to blatant violence to obtain wealth.

Power derives not from political prestige but from the background wealth and influence that makes it possible. Because of this, secret societies and tongs were common in Chinatowns throughout America. They controlled key facets of these communities, including jobs and credit. Only by seeking their protection could new Chinese immigrants hope to survive in America. Each tong operated within its own designated territory and managed brothels, casinos, and opium dens. Acting out of self-interest, corrupt American courts, policemen, and political groups fueled the flames of conflict between various gangs.

Tom Lee’s Loon Ye Tong (which later became On Leong Tong) was the largest tong in New York City. The struggle for wealth in New York’s Chinatown was primarily between On Leong Tong and Hip Sing Tong, a rival gang. According to a report from The Sun newspaper, in summer 1894, Tom Lee’s influence gradually began to decline following challenges from the West Coast-based Hip Sing Tong. He slowly lost his position of absolute power in Chinatown.

Hip Sing Tong formed branches on the East Coast in the late 1880s(15), forming a branch in Philadelphia in 1889 and one in Washington D.C. in 1995. At the same time, On Leong Tong formed branches in Boston (spearheaded by Meitong Seetoo in 1905), Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. Both tongs had sizeable influence in Chicago(16). For tongs that were spread across state lines, a conflict in a given region could lead to violence across the country.

In New York, Tom Lee’s On Leong Tong found political protection in Tammany Hall. Tammany Hall’s primary rivals were the Methodists. With the help of lawyer Frank Moss, Methodist leader and social reformer Charles Parkhurst sought to restore moral order to Chinatown. His goal was to use the Hip Sing Tong to oppose and eliminate the corruption and vices brought about by the On Leong Tong.

New York’s Chinatown appeared like an impenetrable fortress from the outside, yet its foundation was decrepit, crumbling, and susceptible to collapse. Wong Get, the secretary and spokesperson for Hip Sing Tong, understood this fact well. Despite his lower status, he was able to secure the moral high ground, time his opportunity, and attack the powerful Tom Lee. As a witness, he exposed Tom Lee and On Leong Tong’s despicable actions in court in 1894. For this, Hip Sing Tong was lauded and known as the Chinese Parkhurst(17).

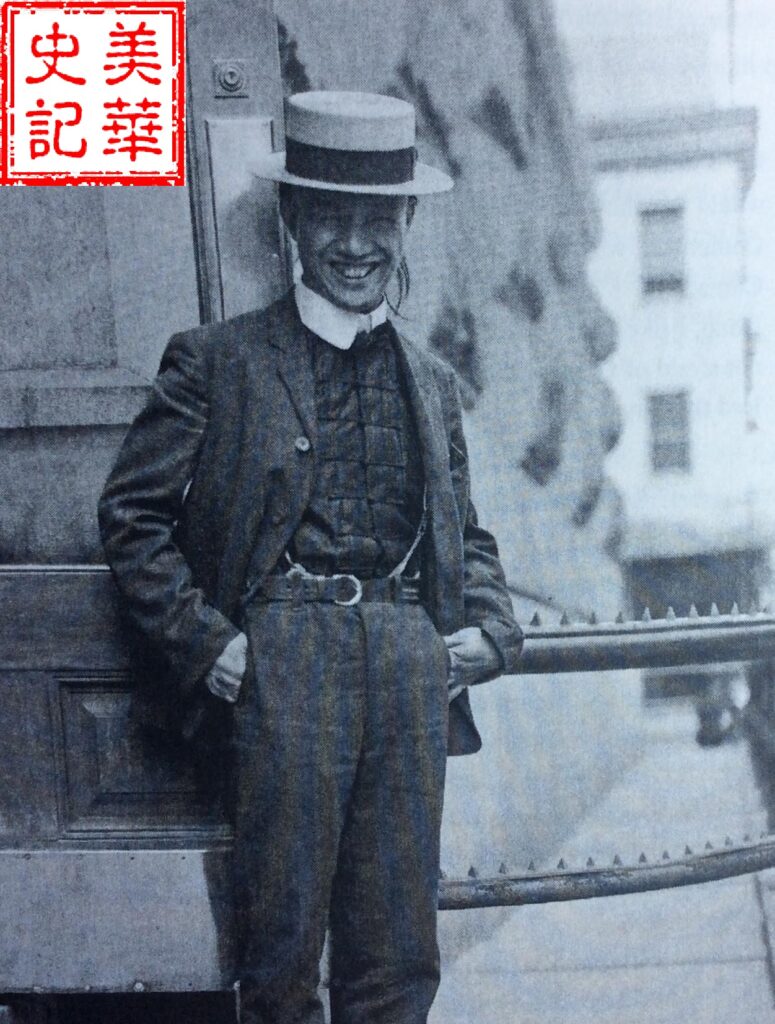

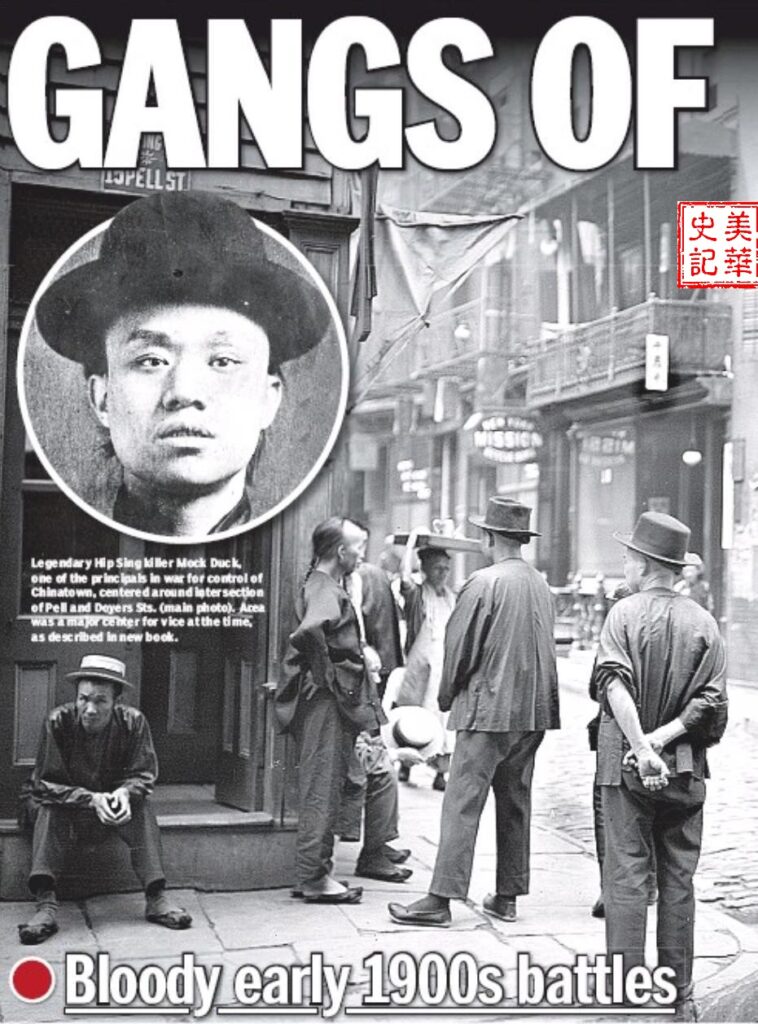

For leaders, toughness is an essential characteristic. Hip Sing Tong’s leader Sai Wing Mock (Mock Duck) certainly had this character trait. In the early 1900s, he led the Hip Sing Tong in challenging On Leong Tong’s authority and made a name for himself in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Whereas On Leong Tong’s success came as a result of bribing cops and officials, Hip Sing Tong’s influence was won as a result of its members’ toils and efforts(18).

So how did Mock Duck make his fortune, and become one of New York’s most prominent crime bosses? Mock Duck was born in San Francisco in 1879 (although this has not been confirmed via official records), and arrived in New York’s Chinatown in 1895(19). He was of medium build among Chinese, standing at 5’6” and weighing 125 pounds. Mock Duck had a handsome, friendly appearance that belied a courageous heart. Mock Duck constantly braved danger in his everyday life and was nicknamed the Clay Pigeon of Chinatown and the Mayor of Chinatown by the media. According to reports, he always had a pair of .45 revolvers on his person as well as an axe. His battle prowess was renowned as well – in conflicts, he would crouch down and fire at his opponents with his eyes closed in an extraordinary manner(20).

Image 6: Mock Duck (1879 – July 23, 1941). Sourced via Scott D. Seligman, “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown. New York: Viking-Penguin.” 2016: p.60.

In reality, Mock Duck was not a typical ally of the Methodists and had numerous gang affiliations and businesses. He even took over On Leong Tong’s most prosperous business activities. Chinese gangs fought fiercely to control the opium, prostitution, and gambling businesses, and the weapons of conflict gradually escalated from axes and blades to handguns and automatic weapons. At times, bombs were even used. Inter-gang conflicts transformed the Chinatown of America’s largest city into a battlefield.

In 1900, Mock Duck challenged Tom Lee and demanded that he give up half of the illegal gambling business. Within 48 hours of Tom Lee’s refusal, Mock Duck declared war on the On Leong Tong. A male member of Hip Sing Tong set fire to Tom Lee’s residence (in 1908), leading to the death of two men inside the house. In another conflict, an On Leong Tong member was decapitated by two members of the Hip Sing Tong. This marked the beginning of open conflict in Chinatown between the two tongs (21, 22).

War: War is the clash between the civil and savage aspects of our natures. It is to use blood and death to coerce the opposition into accepting unequal conditions and to force them to submit to one’s will.

In war, the winners get the respect and victory they want, while the defeated side stands to lose everything. Of course, even losers will not give up their territory easily and cave fully to the victor’s demands. As a result, violent clashes between New York’s Chinatown gangs continued to occur sporadically for nearly 30 years. This resulted not only in the death of Chinese immigrants and damage to their property, but also destroyed the reputation of Chinese communities. On Leong Tong used to run Manhattan’s Chinatown, but its control was challenged by both the Hip Sing Tong and the Loong Kong Tien Yee Association, resulting in two major tong wars. After the tong wars, On Leong Tong’s influence weakened by the day, and Hip Sing Tong was poised to take over and establish its dominance.

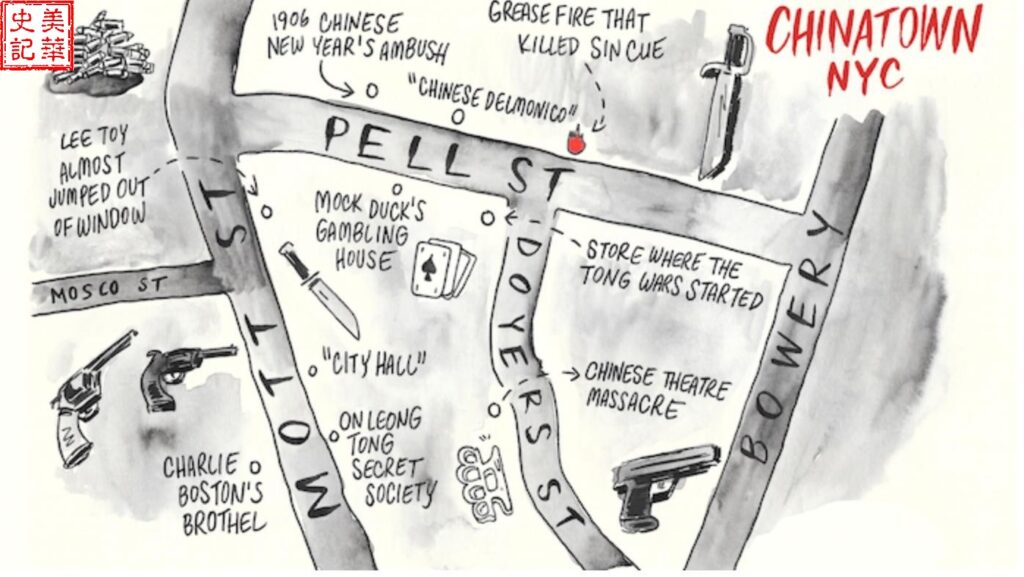

The First Tong War Was Fought Over Gambling

Lung Kin of Hip Sing Tong worked at a laundry on Amsterdam Avenue. He would often go to Chinatown on Sundays. For unknown reasons, on August 12, 1900, he went the 9 Pell Street instead. As described by The New York Times, it was “a gloomy five-story building that was filled with countless dens passing as bedrooms, and carried a disgusting smell.” Around 6 pm, there was an altercation in a narrow hallway. It is unknown how many people were involved – it could be six, twelve, or even up to eighteen. Media reporting on this incident was extremely uncoordinated, but they agree that the crowd scattered after two gunshots were heard. They left behind Lung Kin, who had sustained mortal injuries and was laying in a pool of his own blood.

Not only after this, the police arrested a suspect on the second floor of an apartment building across the street. It was Gong Wing Chung of On Leong Tong. The Times described the killer as such: “When faced with the murder charge, he had no reaction; when he was taken away, there was a smile on his face.” In this incident, the slain was a member of Hip Sing Tong. Within six weeks, an On Leong Tong member named Ah Fee (1857-1900) was killed in retaliation. He just so happened to be a witness that was testifying that Gong Wing Chung was not present at the scene of the crime. On the surface, it looked like this incident arose because Gong Wing Chung blamed his gambling losses on Lung Kin’s deception; in reality, it was an orchestrated killing by On Leong Tong. There were four Hip Sing Tong members on the list of targets; the other three aside from Lung Kin survived (23).

Image 7: In 1900, Mock Duck allied with clergyman Charles Parkhurst and pretended to be an “honest businessman”. He provided Parkhurst with evidence and information regarding On Leong Tong’s crimes, including addresses related to criminal activity on Pell and Doyers Street. Authorities conducted a raid on On Leong Tong’s opium dens and casinos on Pell and Doyers Street. As a result, Mock Duck took control of the advantageous territory around Mott Street (which was the true hotspot of criminal activity) and continued his campaign against Tom Lee. Source: https://www.pressreader.com/usa/new-york-daily-news/20160717/281844347979387

Image 8: Diagram of the Chinatown tong wars. Source: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/population-change-1939-2015

On Easter Sunday, April 23, 1905, Hip Sing Tong orchestrated a police investigation on twelve Chinatown casinos in order to harm On Leong Tong. This was the largest raid in the New York police’s history up to that point(24). That same year, Hip Sing Tong staged another gang massacre at the Chinese Theater on Doyers Street. The Chinese Theater was one of only a few neutral locations in New York’s Chinatown. Without any warning, Hip Sing Tong’s thugs tossed lit explosives into the crowd, filling the area with white smoke and sparks. Afterward, Hip Sing Tong shooters began firing at On Leong Tong members. By the time police arrived at the theater, all four On Leong Tong members at the scene had been killed, and two innocents had perished as well(25).

Mock Duck was the mastermind behind this massacre, and the authorities cracked down on Hip Sing Tong’s outrageous behavior. As the primary suspect behind the Chinese Theater killings, Mock Duck spent most of 1905 behind bars. Hip Sing Tong’s spokesperson Wong Get returned to China for several years to escape the backlash surrounding the incident. After losing its leader, Hip Sing Tong quickly weakened(26).

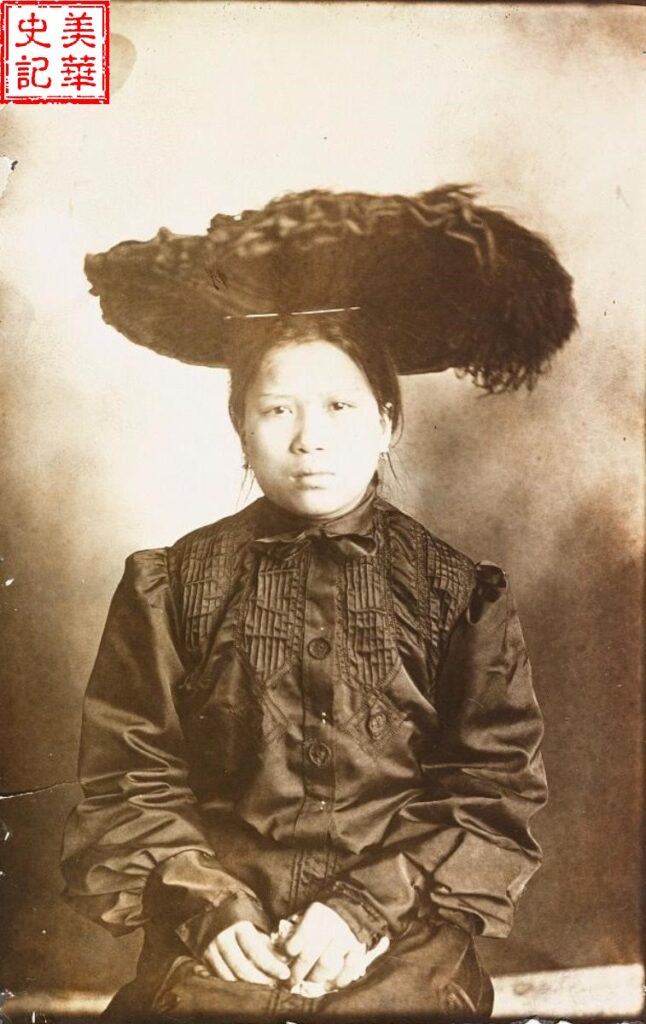

At this time, Mock Duck’s gang activities were running into roadblocks, and he was facing emotional troubles as well. In 1906, Mock Duck married his first official wife Tai Yow Chin. Tai was a widow; her previous Chinese husband had passed away, leaving her with a mixed-race daughter Hai Qi (1901-?) that he had in his previous marriage to a white woman. Although they were step-parents, Mock Duck and Tai Yow Chin were very loving to this stepdaughter. On March 19, 1907, the members of a child protection organization (the Gerry Society) and two police officers knocked on Mock Duck’s door. They had received a report that claimed Hai Qi was kidnapped from a white family and had been abused by the Chinese community, having been forced to wear Chinese clothing and had her blonde hair dyed black. Mock Duck and his wife’s explanations fell on deaf ears, and the child was forcibly taken away from them(27).

Image 9: Mock Duck’s wife Tai Yow Chin. Image sourced via Scott D. Seligman, “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown. New York: Viking-Penguin.” 2016: p.145

This incident hurt Mock Duck deeply. Even though he was a hardened leader, and had been to jail twice for orchestrating murders, he still collapsed sobbing on his child’s bed. In order to win back custody of his daughter, Mock Duck sued, but lost. He tried to sue again, and was denied once more. Because of her appearance, the court did not accept that Hai Qi had Chinese heritage. With his criminal history, Mock Duck had no way to prove he was a qualified guardian. As a result, the case went all the way to the highest court, and he still never won back custody(27). Shame and hopelessness overwhelmed Mock Duck, who went west to San Francisco, Chicago, and other cities and gambled mindlessly, with no regard for the outcome. In reality, he won big as a result of his gambling. When he returned to New York, he had shiny diamond studs on his shirt, and more than $30,000 in his pocket(28).

Mock Duck returned to the battlefield of Manhattan’s Chinatown(28) with the intention of revitalizing Hip Sing Tong. Before long, Hip Sing Tong won control over large portions of Pell Street from On Leong Tong, and the war between the two factions was back on. This conflict raged until 1909 and drew the attention of the news media.

The Second Tong War Was Fought Over Women

This tong war happened in 1909, and was waged by the “Four Brothers” Lau, Kwan, Cheung, and Chu of the Loong Kong Tien Yee Association against the On Leong Tong. The passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act contributed to a severe gender imbalance and lack of women in Chinese American communities, which was one of the reasons behind this tong war. In Chinatown, a Chinese women would receive attention from hundreds of Chinese men. Because there were too few Chinese women, Chinese men of means would often marry Irish or Italian women, who were also considered to be of lower social standing. Around the year 1900, children became common in Chinatown, many of whom were mixed race.

Bow Kum (1888-1909) was born in China and was a sex slave in the San Francisco home of Loong Kong Tien Yee Association member Lau Tong. After being rescued by Presbyterian ministers, she married an On Leong Tong laundry worker named Chin Lem and moved to New York. Lau tried to get his “property” back, but failed to do so. After this, he demanded $3,000 ($80,000 in today’s money) from Chin Lem as compensation and was once again denied(28).

The two men’s contest over Bow Kum eventually escalated to On Leong Tong leadership, who sought to remediate the issue. On Leong Tong ruled: this woman was rescued by the church, so Chin did not have to return her to Lau and did not have to pay him any compensation. This decision by On Leong Tong led to Bow Kum’s subsequent death. On August 15, 1909, 21-year old Bow Kum was murdered and dismembered in an apartment at 17 Mott Street. When police arrived, they found an exceptionally grisly scene. The victim’s heart had been stabbed twice, and a seven-inch long hunting knife was stabbed into the floor next to the body. This was the beginning of a series of retaliatory murders carried out by Chinese gangs over women.

In order to strike out at On Leong Tong, in 1910, the Loong Kong Tien Yee Association allied with the enemy of its enemy, the Hip Sing Tong. To face their mutual foe, the Hip Sing Tong eagerly joined this conflict which it originally had no part of. At the time, Charlie Boston (formerly named Lee Quan Jung, 1866-1930) was in control of On Leong Tong and led its members in opposition against the two rival gangs. As a result, Chinatown’s major tongs fell into bloody conflict(28).

If no one was killed, the Chinese would seldom petition for help from the police and the courts and would elect to resolve issues internally. Once the tong war began, it was hard to stop. In order to save face, the gangs would often have to go through lengthy negotiations in order to agree to a ceasefire. To end this war, the Chinese ambassador and the Six Companies had to step in to finally facilitate a peaceful resolution. This peace agreement was very respectful of each gang’s interests and authority and clearly defined each group’s territory. It was like an underground code that maintained the peace in New York’s Chinatown for a period of time. Each tong’s territory in Manhattan gradually stabilized – Mott Street belonged to On Leong Tong, Pell Street was Hip Sing Tong’s, and Doyers Street was communal land(29). The ceasefire was accompanied by declarations of peace, fireworks, and celebrations. The tongs would put their money and lives on the line to establish dominance in a repeating cycle. In the end, those who suffered most were the normal Chinese immigrants who had no choice but to ally themselves with the tongs.

Image 10: The only photo of Bow Kum. She was murdered at 17 Mott Street on August 15, 1909. Image sourced via Scott D. Seligman, “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown. New York: Viking-Penguin.” 2016: p161

The Third Tong War Was Fought Over the Opium Trade

In the previous tong wars, Hip Sing Tong used its alliance with Charles Parkhurst to gain control over half of New York’s Chinatown. This time, they planned to repeat the same trick and break into the lucrative opium business with help from the government, taking over the drug market from On Leong Tong. On January 25, 1911, investigators from the federal customs office discovered that over the course of several months, hundreds of thousands of dollars of opium had been shipped to a few Chinese in East Coast cities. In order to gather evidence, the officials disguised themselves to appear unkempt and homeless and tried to buy drugs at two stores. Both stores sold them opium that was packaged to resemble lychees and nuts. After obtaining irrefutable evidence, authorities prepared to arrest the dealers. In an attempt to avoid arrest, four Chinese drew weapons but were subdued before they were able to fire them. The cops had a successful outing – in addition to drug-manufacturing equipment, they seized over $10,000 of opium(30).

Starting in 1909, it became a federal crime to import opium. There was extensive evidence of a massive underground drug network that had tacit support from the police in several cities. With Tom Lee’s support from behind the scenes, Lee Quan Jung led On Leong Tong in controlling this crime network that dealt opium throughout the nation. Gin Gum (1863-1915) was On Leong Tong’s longtime underwriter. When investigated by federal officials, Lee Quan Jung was arrested in front of On Leong Tong headquarters on Mott Street(30).

On Leong Tong quickly figured out that Hip Sing Tong was responsible for reporting them to customs officials, but did not immediately retaliate. On December 12, 1911, Lee Quan Jung was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison in addition to three years of probation afterwards. A week later, Lee Quan Jung was sent to the Atlanta Penitentiary to serve out his sentence. At that time, news of the 1911 Chinese Revolution spread to New York’s Chinatown. Chinese communities worked together and raised more than $75,000 to support the anti-imperialist revolution(30).

In his interview with The Sun newspaper, Tom Lee claimed that brotherly ties were strong between the various gangs. He even openly praised Hip Sing Tong leader Mock Duck’s patriotism. Tom Lee announced that the rivalries and hostilities between gangs would evaporate alongside the fall of the Qing Dynasty. In January 1912, to celebrate the founding of the Republic of China, hundreds of thousands of fireworks were set off above Chinatown and thousands gathered in attendance. Sun Yat-sen’s portrait and the Chinese flag were all over Chinatown, and the Chinese let go of prior tensions(30).

However, this peace only lasted a few days. The third great tong war, which would last ten years, was about to begin. On January 5, 1912, four members of On Leong Tong snuck into 21 Pell Street and ambushed Hip Sing Tong. On Leong Tong shooters fired over 20 shots. One person was killed on the spot and another died the next day after being gravely injured. Mock Duck was there at the time but fortunately avoided getting shot. Subsequently, a Hip Sing Tong member led the police to On Leong Tong and arrested two shooters. Due to charges of murder and gambling, Lee Quan Jung of On Leong Tong and Mock Duck of Hip Sing Tong were both imprisoned. In reality, this tong war was fought over control of the New York opium trade(30).

Chinese gangs continued their bloody underground battles while pretending to be harmonious and united in public. In the second half of 1912, On Leong Tong threw a celebration in Manhattan that was attended by 2,000 people and lasted 11 days. The celebration was thrown in order to celebrate the completion of On Leong Tong headquarters at 42 Mott Street, a project that cost $150,000. On Leong Tong not only invited Hip Sing Tong members to this celebration, they also sent a ten-foot wreath of flowers to the funeral services of Fong Foo Leung, (the former leader of Hip Sing Tong) in July 1922 to pay their respects(30). American media expressed confusion at this simultaneous combination of violent warfare and brotherly compassion present among tong members.

Over the years of conflict, Mock Duck was involved with many major or minor skirmishes and was arrested several times. In 1912, the court sentenced Hip Sing Tong leader Mock Duck to two years behind bars at Sing Sing Prison for running illegal gambling operations. In 1914, after Mock Duck was released, he announced via the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that he vowed to become a respectable citizen. He changed his ways, moved to Brooklyn, and left the tong life behind(22).

At the same time, Tom Lee also stepped away from gang life in 1916 and refused to take part in any conflicts. On January 10, 1918, the once-vigorous Tom Lee fell asleep in bed, never to wake again(32). A lengthy procession went to 18 Mott Street to pay their respects, including members of Hip Sing Tong and Loong Kong Tien Yee Association, political figures, businessmen, laundry workers, and regular citizens. Both whites and Chinese were in attendance. On the day of Tom Lee’s funeral, all stores in Manhattan’s Chinatown closed and thousands of people took to the streets as part of the funeral procession. Tom Lee, although not loved by all, was deeply respected and looked up to. A hero of his time bid farewell to New York’s Chinatown!

Reputation: Reputation is our face to the world, and an evaluation of character, ability, personality, and dignity. In New York’s Chinatown, a man’s reputation was essential. The torrents of the Yangtze wash away heroes of yore; right or wrong, success or failure, all are no more.

Image 11: Tom Lee was initially buried at Cypress Hills Cemetery, but was moved three months later. According to his last wishes, he was accompanied back to Guangdong, China by his son Frank William Lee. Image source: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/359795457724332496/

In 1917, America declared war against Germany and the First World War began. According to the law, males aged 18 to 25 were required to join the military. Non-citizens did not have to participate in battle, but had to sign up. Around 1920, 30% of Chinese Americans were naturalized citizens who were born in the United States. In New York’s Chinatown, over 100 Chinese chose to fight under the star spangled banner, and even more served in support capacities during the war(33).

According to records, 38 members of On Leong Tong fought in the war. On Leong Tong leader Lou Fook bought $50 war bonds. Although very few among them were American citizens, many Chinese merchants in America bought war bonds. In April 1918, the Chinese on Mott Street organized a parade to promote buying war bonds, highlighting the patriotism among Chinese Americans(33). New York publication The World published an article about this parade.

In April 1919, Hip Sing Tong, On Leong Tong, and Loong Kong Tien Yee Association threw a joint celebration to welcome the victorious New York Chinese after the war. Those returning included On Leong Tong hero Lau Sing Kee (1896-1967), who was born in Saratoga, California. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the predecessor to the Purple Heart by the United States, as well as the Croix de Guerre from France. Lau Sing Kee braved German artillery and gas, fighting at a recon station for three days. He even held the line alone for 24 hours, successfully delivering vital wartime intelligence. Chinatown threw a massive welcome parade and banquet for Lau Sing Kee and other returning heroes(33).

Image 12: On Leong Tong hero Lau Sing Kee. Image source: https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/commemorate/family-ties/stories-of-service/2207-lau-sing-kee.html

Image 13: On December 1, 1922, police and federal officials searched Hip Sing Tong headquarters and found thousands of dollars of morphine in addition to poppy heads, from which morphine could be extracted. At the same time, they confiscated a large number of firearms. The third tong war thus came to an end(p221). Image source: https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/scott-seligmans-tong-wars-the-untold-story-of-vice-money-and-murder-in-new-yorks-chinatown

Loyalty: Loyalty is the bond that helps one resist temptation and choose which causes to devote one’s time and effort to. Loyalty and emotional connection are intricately linked, and loyalty allows love of a group, organization, or country. Loyalty cannot be forced.

The Fourth Tong War was Fought Because On Leong Tong Members Joined Hip Sing Tong

The one who initiated the war was Chin Jack Lem (1878-1914), who had led On Leong Tong’s Chicago chapter for more than twenty years. In April 1924, when On Leong Tong held its annual conference in Pittsburgh, Chin and 13 other members of his gang ran into a dispute with On Leong Tong over funding. In a rage, Chin secretly became a member of Hip Sing Tong and pledged to bring Pittsburgh and Cleveland members of On Leong Tong under Hip Sing Tong’s wing. Once the news got out, On Leong Tong treasurer Wong Sing called the police, claiming that Chin extorted him into signing over $70,000 worth of tong funds. Afterwards, On Leong Tong chapters in Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Chicago all received threatening letters. Although there were heated internal debates on the matter, Hip Sing Tong ultimately agreed to let the On Leong Tong members join. This led to yet another tong war, which claimed the lives of 41 people in just six months.

The two tongs called upon members from all over the United States and even in Hong Kong to join the battle. The weapons of war escalated into automatic firearms and bombs, making it exceptionally difficult to get the conflict under control. The fighting raged on until fall 1929(34). In the end, both sides suffered heavy losses. Around this time, Tammany Hall lost its political influence, which greatly weakened On Leong Tong’s control as well. In addition, the police redoubled their efforts to shut down casinos and brothels, arresting and sentencing perpetrators. Some were even executed when found guilty of murder. The courts and federal government stepped in to force an end to the conflict, even deporting several Chinese(35).

In the 1930s, the Great Depression weakened not only the American economy but each tong’s financial strength and ability to wage conflict. In 1931, 25% of Chinese Americans had lost their jobs and many called upon the tongs to provide benefits. As a deeply connected community, the Chinese chose to endure poverty, fear, and hardship together. The Great Depression severely impacted Chinatown – in 1930 alone, more than 150 Chinese restaurants went out of business and 25% of the population was unemployed. By mid-1932, more than 4,000 Chinese were unemployed in New York City. The city provided aid to the poor, but this aid flowed to whites and Blacks – not a single Chinese received relief funding. The Chinese were solely dependent on mutual aid in Chinatown. The tongs no longer fought and united in their effort to help the poor(36).

The media were dumbfounded and thought the Chinatown gangs were playing a joke. Interactions between tongs led to speculation from those on the outside. On April 27, 1931, On Leong Tong and Hip Sing Tong threw a joint national convention in New York. On Leong Tong was based out of 41 Mott Street, while Hip Sing Tong was at 13 Pell Street. Amid shouts, thousands of Chinese crowded together in Manhattan. It seemed like war would break out at any moment, unnerving the outside world, yet there ended up being no conflict(37)!

Image 14: Hip Sing Tong’s parade on Pell Street during the national convention. In the distance On Leong Tong flags are visible. Image sourced via Scott D. Seligman, “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown. New York: Viking-Penguin.” 2016: p249

New York’s Chinatown tongs were forced to evolve and change due to global events. In 1931, the Japanese invasion of China began. In addition to supporting the poor, the tongs had to provide for the war effort to help China resist Japan. On Leong Tong and Hip Sing Tong allied together and scheduled regular meetings to gather donations for China. New York’s Chinatown alone successfully raised over $1 million. They claimed, we are all Chinese, we must help China(38).

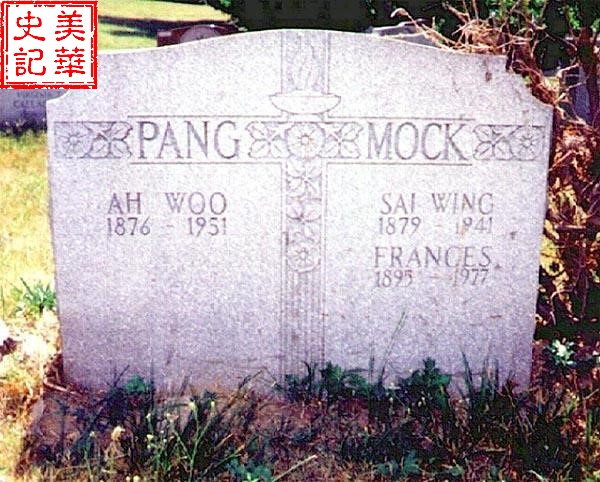

In 1932, Mock Duck came to an agreement with the U.S. and Chinese governments, declaring an end to the Chinatown tong wars. He then retired peacefully to Brooklyn, where he died of tuberculosis on July 23, 1941. He was buried at Cypress Hills Cemetery with not his official wife but his latter one Frances Toy Yuen (1894-1945), in addition to a mysterious boatman(39, 40). Mock Duck’s burial arrangements remain an unsolved mystery.

Image 15: Mock Duck’s gravestone. Source: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5931/mock-duck

Crime: Crime is an act that breaches both morality and legality. The innocents who are punished often bear the guilt for those who are guilty or even actually responsible for the crime. It is often unclear what is truly right of fair, and those who administer justice need to open their minds and self-reflect. The tong wars arose as a result of systematic injustices against the Chinese, yet they themselves exacerbated the suffering of Chinese Americans.

Long periods of exclusionary policies led to a severe gender imbalance in Chinese communities. Statistics show, in 1860 the ratio of Chinese men to women was 20:1. By 1890 this ratio had risen to 27:1. Even in 1930, this ratio was still 4:1(41). Many Chinese were unable to form families and have children. Single men without any women nearby took to brothels, gambling, and opium to indulge their urges. From 1900 to 1927, of the Chinese arrested in America, 2/3 were involved in one of three criminal acts: visiting brothels, gambling, or using drugs(42).

The Chinese were not treated equally under the law and turned to tongs for mutual aid and assistance. Despite the tong wars, which horrified the outside media, the majority of Chinese Americans were peaceful(41). White criminals and scoundrels also frequented Chinatown’s red light district, which made the area even more dangerous. This strengthened the argument for exclusion from those who were anti-Chinese.

Many people were afraid of going to Chinatown. The New York World claimed that Chinatown was New York’s worst slum, and was a hive of filth, crime, and nastiness. In reality, all of New York was a hub for criminal activity for half a century, with violent crimes being perpetuated by Irish, Italian, and Jewish mobs. Their behavior was even worse than that of the Chinatown tongs. In 1904, 334 Chinese were arrested, in comparison to 20,000 Irish, 13,000 Italians, 12,000 Russians, and 11,000 Germans(42).

Yet the news world was not interested in reporting on the crimes of Europeans, and focused their time on drawing attention to those committed by the Chinese. Irish-born William McAdoo (1853-1930), who served as New York City’s police chief from 1902-1906 and later served as chief magistrate of the city magistrates’ courts, did not even admit to the existence of systematic crime by Italians. He claimed, “the Mafia are made up, I do not believe in them (44).”

Systematic discrimination is an injustice. The rise of the Chinese Exclusion Act had already proven the legality of discriminating against the Chinese, which forced the Chinese to segregate within Chinatown and its associated criminal activity. This delayed their assimilation into American culture and society.

Friendship, power, wealth, war, reputation, loyalty, and crime…human nature is as ancient and unchanging as the face of a mountain.

Image 16: The crowded Mott Street in today’s New York Chinatown (former On Leong Tong territory). Image source: https://goo.gl/images/HnrxVy

Image 17: The beautiful Pell Street after a rainfall (former Hip Sing Tong territory). Image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vivnsect/7874191038

Sources:

2. https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/population-change-1939-2015

3. Scott D. Seligman, “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown. New York: Viking-Penguin.” 2016: P1-3

4. Seligman, 2016: P4-5

5. Seligman, 2016: P5-7

6. Seligman, 2016: P9-10

7. Seligman, 2016: P11-13

8. Tammany Hall,AMERICAN POLITICAL HISTORY. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tammany-Hall

9. Seligman, 2016: P14-15

10.Seligman, 2016: P16-26

11. Seligman, 2016: P29

12. Seligman, 2016: P34-35

13.”The People’s Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)”. U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

14. “Scott Act (1888)”. Harpweek. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

15. Seligman, 2016: P39

16. Seligman, 2016: P149

17. Seligman, 2016: P42-56

18.Seligman, 2016: P51

19. Seligman, 2016: P61

20. http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/09/story-sai-wing-mock-mayor-chinatown/

21https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5931/mock-duck

22. Stephen C Duer , By (author) Allan B Smith,“Cypress Hills Cemetery”。 Publisher Arcadia Publishing (SC),2010

23.Seligman, 2016: P66

24. Seligman, 2016: P93-125

25. https://infamousnewyork.com/2013/09/01/the-chinese-theater-massacre/

26. Seligman, 2016: P138

27. Seligman, 2016: P144-148

28. Seligman, 2016: P156-170

29. Seligman, 2016: P132

30. Seligman, 2016: P182-202

31. Seligman, 2016: P220

32. Seligman, 2016: P125-126

33. Seligman, 2016: P218

34. Seligman, 2016: P223-233

35. Seligman, 2016: P257-258

36. Seligman, 2016: P243

37. Seligman, 2016: P248-250

38. Seligman, 2016: P252

39. Seligman, 2016: P264-265

40. Brooklyn Death Index: “Mock Sai 62 y July 23, 1941 15191 Kings County

41. 托马斯·索威尔 美国种族简史 中信中版社 2011:p523

42. 托马斯·索威尔 , 2011:p531

43. Seligman, 2016: P120

44. Seligman, 2016: P122