Xin Su

Unlike the island on the East Coast, the Ellis Island Immigration Station in New York that welcomed European immigrants to the United States, Angel Island at San Francisco, Califonia received immigrants from Asian countries. About 80% of applicants passed the Ellis Island immigration inspection and medical examination and were on their way to New York or New Jersey within hours. On Angel Island, nearly 60% of immigrants were detained and confined for up to three days. For Chinese immigrants, who made up 70% of the entire detainee population, the average stay duration was two to three weeks. They were subject to scrutiny for days, weeks, or even years [1].

When ships arrived in San Francisco, most Europeans and first-class passengers were able to disembark freely; Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian immigrants, as well as those from countries such as Russia and Mexico, were ferried to Angel Island and detained for questioning and medical examinations. At the hospital, most immigrants were required to undress and line up in groups to be physically examined and screened for disease, a humiliating process. It should be noted that this humiliating treatment was only targeting on a specific race.

This overtly racist procedure at Angel Island Immigration Station legally existed for 30 years along with the 60-year long of the Chinese Exlusion Act. The United States Congress approved the construction of an immigration station on Angel Island in 1905. The immigration station was completed in 1908 and officially opened in 1910. [2] In 1940, a fire destroyed the administration building on the island, and immigration was then forced to move to the city of San Francisco. An estimated half a million people, a majority from China, Japan and other Asian countries, passed through Angel Island in the 30 years it was active [3].

Anti-Chinese Immigration Walls Built on the North and South Borders

While the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 closed the legal door for immigration, many Chinese switched their tactics by entering the country illegally and they probably became US’ first illegal immigrants. Moreover, these illegal Chinese immigrants who had sneaked into the US through Canada, Mexico, or unguarded shores might have set a precedent for future unlawful immigrants.

They endured many hardships, hid in any possible means of transportation or cargo, bribed officials and intermediaries, risked their lives to break through barriers, and lived shameful lives because of their illegal identities, just to enter the US.

This made the Chinese, a group of people from the prosperous but declining Qing Empire, the first and largest number of illegal immigrants in the US at the time [4]. To prevent the breach of its border by illicit immigrants, the US government hence began to extend its border security to its neighbors such as border diplomacy in Canada and border policing near the border with Mexico. Despite the effective border security in both northern and southern sides, some Chinese managed to take advantage of legal loopholes to acquire admission to the country as legal immigrants or even citizens.

In fact, since the signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, illegal immigrants were no longer a myth: beginning from the Atlantic Gulf in the east, to the Pacific Port in the west, Canada in the north, and Mexico in the south, illegal Chinese immigrants flooded into the country. The huge profits made by officials who allowed illegal immigrants to enter caused immigration to be repeatedly banned from the Chinese [5].

For example, one immigrant did not bribe the translator when he entered customs in Boston, and the translator told the immigration officer that his document was forged. As a result, he was sent home. In desperation, he paid $6,500 to get smuggled back in. He had borrowed the money, and it took 20 years of work to pay it off [6].

There were both European and Asian illegal immigrants, but Europeans were eagerly welcomed by the United States, whereas Asian immigrants were looked down upon, thus the Chinese had to smuggle themselves in [4].

The United States wanted to work with its neighbors in the north and south to deal with the illegal immigrants. However, the north and south borders operated differently. In the north, US efforts centered on border diplomacy based on a historically amicable diplomatic relationship and a shared antipathy for Chinese immigration. In contrast, US control over the southern border relies less upon cooperation with Mexico and more upon border policing, a system of surveillance, patrols, apprehension, and deportation [7,8].

There were two types of illegal immigrants from Canada. The first type was the Chinese who came to the US and had to cross the border to work in Canada. After the Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted, it would be difficult for them to return to the United States. The second type were those who went directly to Canada from China in order to reach the US. The border between the United States and Canada was wide and unattended to, so it was very easy for Chinese Canadians to cross the border to the United States [7]. An American journalist estimated that 99% of the Chinese arriving in Canada intended to “smuggle themselves over our border” [7].

Early on, Canada allowed Chinese people to pay head tax to enter. For example, in 1900, it cost each person 100 US dollars to enter, but in 1903, the fee grew to 500 US dollars per person. An Oregon magazine editor complained: “Canada gets the money, and we get the Chinamen.” It was true that Canada’s northern border had generated a steady stream of wealth. So at the beginning, the Canadian government was unwilling to actively cooperate [9,10].

Under constant pressure from the United States and the threat of closing the border, the United States and the Canadian Pacific Railway Transportation Company reached an agreement in 1903. All Chinese visitors must be checked to see if they meet the requirements for entering the United States. After the inspection, the qualified persons were sent to the designated U.S. border post for inspection. Those who passed the inspection would get a passport to enter the United States, and those who failed the inspection would return to Canada [10].

At the same time, the U.S. government realized that the acceptance of the Chinese from Canada would bring potential pressure for illegal immigration to the U.S. In 1908, the United States put further pressure on Canada, hoping for them to enact a Chinese Exclusion Act, similar to the one the US had in place. In 1912, Canada finally agreed to reject the Chinese who had been barred from entry by the United States. Under the dual pressure of the anti-Chinese sentiment by the US government and its private sector, Canada overhauled its Chinese immigration policies altogether to more closely mirror U.S. law. In 1923, Canada abolished the head-tax system and implemented the Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act [11].

Compared to Canada, the border situation in Mexico was very different. The boundary between the United States and Mexico was very vague, and it was difficult to tell if one was standing in Mexico or on the territory of the United States. Since the entry of a large number of Chinese promoted local economic development and provided products and services, Mexico’s President Diaz believed that if Chinese immigration were controlled like the United States, Mexico would lose a lot of valuable labor, so they were willing to accept Chinese labor. Mexican officials not only did not cooperate with the request of the United States, but also openly resisted it [12,13].

Some Mexican citizens and gangs helped the Chinese cross the border illegally and made a lot of money. One proudly said, “I have just brought seven yellow boys over and got $225 for that so you can see I am doing very well here.” [14] It is estimated that 80% of Chinese arriving Mexican seaports would eventually cross the border [14]. Some Chinese people disguised themselves as Indians or Mexicans and crossed the border [15].

However, there were also Mexicans who helped the US Immigration Service catch smuggling. The US government offered rewards to those who provided intelligence on both sides of the US-Mexico border or helped catch illegal immigrants. These spies took photos of suspicious-looking immigrants and then sent them to boarder patrol. The clever spies were able to observe all sorts of suspicious people. Patrolling the border included all possible passages, pedestrian routes, car and train routes. In 1909, a comprehensive and systematic defense network was established. If the illegals were caught, they would face the fate of being brutally repatriated [16]. At the same time, anti-Chinese sentiment and anti-Chinese incidents began to grow in Mexico.

Immigration statistics showed that boarder surveillance, policing and deportation were very successful in preventing illegal immigrants from entering Mexico. The Chinese deported in 1898 accounted for 4% of those who entered Mexico, and in 1904 this percentage rose to 61%. In 1911, US border guard officials proudly declared that it was “no longer acting upon the defensive.” [17].

Border diplomacy with Canada and strengthened supervision of the US-Mexico border had been implemented, and the United States had effectively built a “wall” to prevent illegal immigration in both the north and south, which greatly reduced the problem of illegal immigration.

The gateway to legal immigration: Angel Immigration Island

Because the Immigration Bureau restricted the entry of Chinese labors, many Chinese people began to change strategies to enter the country as merchants or directly as citizens. Because children and grandchildren of citizens can stay, even someone who could have immigrated as a businessman was willing to fake and “become” an American citizen[18]. In this way, immigration became a mind game.

Chinese who were already in the United States claimed that they were born in the United States and that their citizenship had not been registered yet [19]. Many Chinese claimed that the fire caused by the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 burned their birth certificates [20]. Chinese who wished to enter the United States said they were the sons of their mothers who were pregnant and gave birth to their American fathers when they returned to China to visit relatives. In both cases, you can justifiably become a US citizen. After becoming a U.S. citizen, many people created more of these “paper sons” for their families or sold the slots to friends, neighbors, and strangers. [21] Some people often acted as middlemen in this scheme to make money. [22, 23]

Duncan E. McKinley, the Assistant U.S. Attorney, gave a speech at a Chinese exclusion conference in 1901, which reflected the problem of Chinese immigration fraud. He said, “Almost every morning there is a lawyer who claims that a Chinese man in his 20s was born in the United States. Witnesses who are also Chinese appear in court to testify, claiming that they had known the applicant twenty or twenty-five years ago. And that he was born in room 13 on the third floor of 710 Dupont Street. And that when the boy was 2 years old, he was taken by his mother to China for education. Now both parents are dead and relatives in the United States need him to take care of the business. And the uncle or cousin will also be there to swear to prove the truth of the matter. This story is too common, the evidence is solid, and the plan is well planned.” In 1901, a federal judge noted, “If all the stories told in the court were true, every Chinese woman who was in the United States 25 years ago must have had at least 500 children.” [24]

This kind of Chinese “cunning” bewildered immigration officials. For the Chinese, building relationships was more important than the law. According to the Chinese way of thinking, there was nothing immoral about wanting rights to live in a country. These human rights were innate. Since God did not say that the Chinese should not come to the United States, helping innocent Chinese gain entry should also be regarded as a good act. The moral bottom line is that the kin should support and aid one another. In this way, loopholes in the law have allowed populations of ethnic groups to grow [25].

The fire after the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 destroyed all public birth certificates. If there was no document, then the proof of citizenship could only be based on words. In the following years, a large number of “paper sons” appeared in San Francisco. The issue of “paper sons” greatly troubled the Immigration Bureau.

In order to identify the authenticity of these claims and truly implement the Chinese Exclusion Act, local governments in the United States believe it necessary to establish an interrogation process to ensure the truth of these oral claims. At first, the newly arrived Chinese in San Francisco were confined in a windowless two-story building on the side of the Pacific Cruise Line’s dock, which was very dirty and full of the smell of sewage [26]. The government wanted to establish immigration station that could prevent escape and that was isolated to the outside world, so Angel Island was an ideal location.

The island had a beautiful name, because in 1775, a Spanish warship entered the San Francisco Bay for the first time under the command of officer Juan de Ayala. Ayala’s warship docked on the island and gave it a more modern name (Ángeles) [27]. Angel Island used to be a military fortress, a public health service quarantine station, and an immigration office. The immigration station in the northeast corner detained and inspected immigrants from 84 different countries, about 175,000 of which were from China [28].

The bay where the island is located is commonly known as China Cove, because it was mainly used to control the entry of the Chinese into the United States. [29] One of the immigration inspections conducted by the Angel Island customs was routine sanitation and health inspections. Very few Europeans and American citizens were required to be checked and when they were, the doctors fairly abided by the hygiene regulations. [30] However, with the inspection of Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian immigrants, they were harsh and brutal in their inspection. In addition to standard inspections, Chinese immigrants also needed to take stool samples for intestinal parasite testing [29]. The Chinese who were diagnosed with the disease would be sent to the hospital on the island until they could pass the medical examination and immigration hearing. [31]

The interrogation process took an average of 2-3 weeks, but the review of certain immigrants could take up to several months. Each immigrant was interrogated individually by two immigration inspectors and a translator. The immigration officer asked hundreds of questions, including the details of the immigrant’s family and village and the specific circumstances of his or her ancestors, such as “Which direction does the door of your house face?” and “How old is your grandmother?” Their witnesses and other family members living in the United States would be asked the same questions for verification. Any deviation from the testimony would lead to prolonged questioning, and when customs officials suspected anything wrong, the applicant faced the risk of deportation. How did the Chinese overcome this obstacle? They prepared and memorized these details months in advance to make sure every word was perfect.

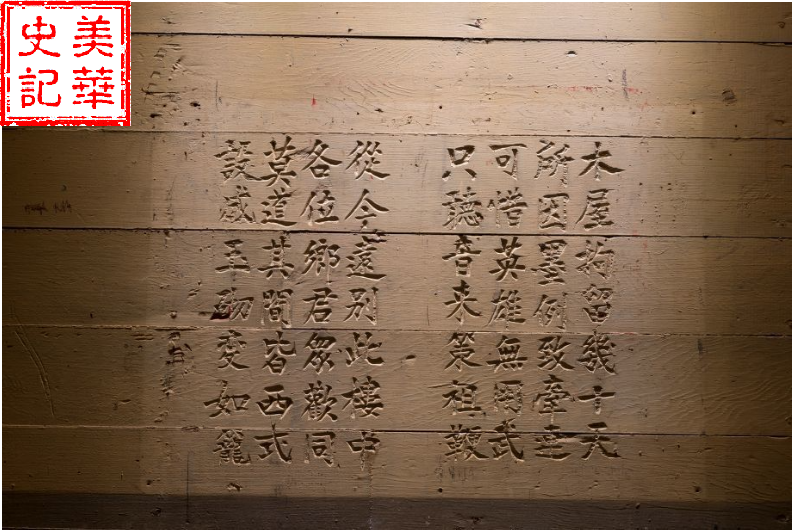

The detention center on Angel Island was like a prison. The door of the barracks was locked all day long, the windows and the walls outside the courtyard were covered with barbed wire, and guards with loaded guns stood guard. Detainees had only a limited number of hours a day to breathe fresh air in the yard. As soon as the detention center was built, the detainees began to carve poems on the walls of the barracks to express their emotions. Three months later, the director of the Island claimed the poems to be graffiti, so he covered it with paint, but the poems were engraved once more. Some of the verses are as follows:

“When I came to America, I was arrested in a wooden building and turned into a prisoner. Americans do not approve of us and turn us back. Upon hearing this news, I am worried about how to return home. China is weak and the Chinese are not allowed here.”

“Trapped in the wooden house, worried and depressed. I wonder how my hometown is. My family wants to know how I am, but who will tell them if I am safe?”

These slightly clumsy, unrhythmic poems have eroded over time, but have not disappeared, expressing the infinite sadness, uncertainty, confusion and indignation of the detainees. These poems were published by well-known Chinese historians Him Mark Lai, Judy Yung, and Genny Lim in 1980. They were compiled, collated, and translated into a Chinese-English Collection of Poems [32] .

“My father came to the United States in 1921 and was detained on Angel Island for two months,” Professor Yang Yuefang said in an interview. “But then he never mentioned this experience to me, mostly because he was a ‘paper son,’ and that memory was not pleasant to him.”[33]

“If you suddenly find out that your last name is fake, how would you feel?” This is what happened to many Chinese-American families who came to the United States before World War II. Though Chinese workers entered the country legally, and tens of thousands of illegal Chinese forged documents to enter the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act was accompanied by corresponding countermeasures and even crimes that occurred among the Chinese, causing generations of Chinese immigrants to live in fear, self-pity, shame, and anxiety. Today, the descendants of “paper son” are uncovering the truth, restoring the truth of their predecessors and allowing future generations to live without this shame.

People of the Future will Remember

The U.S. military continued to use Angel Island as a base during World War II and held Japanese and German prisoners of war here before sending them to camps elsewhere. In 1963 the U.S. military sold Angel Island to California to build a park campground. As a result, the dilapidated buildings of the immigration station began to be demolished. In 1970, Alexander Weiss, a California State Parks ranger, ventured inside the barracks and found by chance that almost every square inch of every room had something carved into the walls. He thought that “there was a whole story to be told”. Weiss told this to his biology professor at San Francisco State University, George Araki; Araki, in turn, reached out to a photographer friend, Mak Takahashi, to help document the poems. The discovery of poetry aroused the attention of community. Christopher Chow, a young journalist, marshaled leaders in the Asian American community, activists and historians. The rediscovery of the poems catalyzed a larger effort to save the barracks and eventually the station itself. [1]

Thanks to the tireless efforts of these people, today we have an opportunity to visit this well-preserved Angel Island immigration station, follow in the footsteps of the early immigrants, walk every part of the land, and read the poems Chinese left on the walls. It often reminds us that we stand against all discrimination and prejudice against specific groups.

Translated by Ella N. Wu.

Reference:

- https://savingplaces.org/stories/messages-from-angel-island-powerful-personal-histories-at-a-former-us-immigration-station#.YqNE66jMI2w

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/Real-story-behind-Angel-Island-17150401.php

- Erika Lee, “At America’s gates : Chinese immigration during the exclusion era, 1882-1943”. (University of North Carolina Press, 2007): P173

- Lee, 2007: P169-172

- Lee, 2007: P148

- Iris Chang, “The Chinese in America: A Narrative History” (Penguin, 2003): P156.

- Lee, 2007: P152-153

- Lee, 2007: P174

- Lee, 2007: P153-154

- Lee, 2007: P176-178

- Lee, 2007: P178-179

- Lee, 2007: P157-158

- Lee, 2007: P179-181

- Lee, 2007: P159

- Lee, 2007: P161

- Lee, 2007: P182-186

- Lee, 2007: P186-187

- Lee, 2007: P112

- Lee, 2007: P106

- Chang, 2003: P145-146

- Lisa See, “‘Paper sons,’ hidden pasts”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Chin, Thomas. “Paper Sons”. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Lee, 2007: P1204

- Duncan E. McKinlay, “Legal Aspects of the Chinese Question”. San Francisco Call. (23 November 1901), Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Lee, 2007: P192

- The National Register of Historic Places (16 August 2007). “Celebrating Asian Heritage”. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- William Bright; Erwin Gustav Gudde (30 November 1998). 1500 California place names: their origin and meaning. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-520-21271-8. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Chang, 2003: P148

- Lee, 2007: P127

- “United States Immigration Station (USIS) « Angel Island Conservancy”. angelisland.org. Archived from the original on 2014-09-16.

- Howard Markel, Alexandra Stern. “Which face? Whose nation?: Immigration, public health, and the construction of disease at America’s ports and borders, 1891-1928”. The American Behavioral Scientist. 42 (9): 1314–1331.

30. Luigi Lucaccini. “The Public Health Service on Angel Island”. Public Health Reports. 111 (January/February 1996): 92–94. - Him Mark Lai and Genny Lim. “Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940” (Naomi B. Pascal Editor’s Endowment) Nov 11, 2014

- “美国天使岛上的华裔移民梦魇 经历奇耻大辱”中国新闻网. 2009. http://news.sohu.com/20090315/n262799197.shtml