Weihua Zhang

This article introduces the readers to Gerald Chan Sieg, who, in spite of many business titles and career accomplishments, took great pride in being the first Chinese American poet in Savannah, Georgia. Born to the first Chinese American family in Savannah, Sieg has never forgotten her cultural roots. Many of her poems depict the early Chinese immigrants’ experience in America, especially in the South. Her poems provide a window into the world of Chinese immigrants: from dealing with loneliness, homesickness, nostalgia, racial discrimination in the early days to embracing family life, community well-beings, beautiful southern landscape, and becoming contributing members of the larger Savannah society.

Sieg’s Poetry

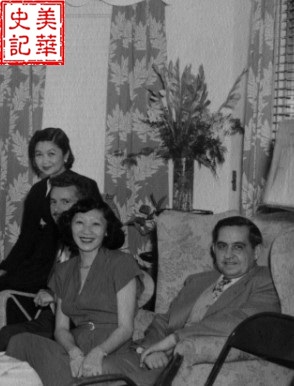

Christened Geraldine at birth, Gerald Chan Sieg was born on October 1, 1909 to Cecelia Ann Lee and Chung Tai-pan (known later as Robert Chung Chan) in Savannah, Georgia. She was the third child and first daughter to the couple, who eventually had 6 children total. Theirs was the first Chinese American family in Savannah, Georgia. On April 6, 1889, shortly after Robert Chung Chan arrived at Savannah while on his way from San Francisco to New York City, he witnessed the “Whirlwind of Fire” that destroyed “some 50 buildings, including 70-year-old Independent Presbyterian Church”1 located on Bull Street in downtown. A devout Christian, Chan joined the firefighters and onlookers to help put out the fire. Afterward, he decided to stay on to help rebuild the church and became a member once the church had been rebuilt. An educated individual, Chan loved to recite classical Chinese poetry at home which had greatly influenced his elder daughter. Years later, Sieg still recalled fondly the rhythms and cadence she heard as a child that led her to writing poetry at a very young age.

Fig. 1. Article on 100-year anniversary of the fire in Savannah

Evening Press, April 6, 1989.

Sieg’s poems are a far cry from the many limitations both her cultures placed on her. In The Far Journey, a collection of her 100 plus poems and published by the Poetry Society of Georgia in 2002, Sieg gives the reader a clear and wide window into her own world and that of her community. Whether laying bare the homesickness of early Chinese immigrants in Savannah, depicting the beauty of low country, confessing the love and loss of her late husband Edward A. Sieg, pinpointing the roots of mistrust between men and women, or peeping into the apprehensions of sickness and old age, Sieg’s poems never lose their elegant touch, exquisite form, unfettered imagination, rhythmical melody, and rich sentiment.

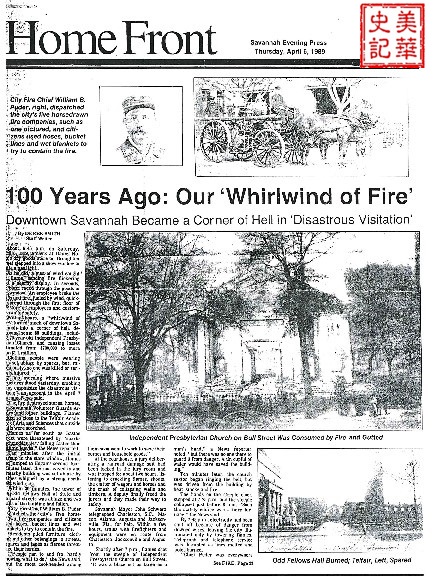

Fig. 2. Sieg’s family c. 1914. Sieg is standing on the left.

“The Sad Lady” is the first poem published by Sieg, in 1927, when she was still in high school and was encouraged to submit by her English teacher. The poem won a prize given by The Poetry Society of Georgia. After that, Sieg was invited to join the Poetry Society in 1928 and remained a member till her death in 2005. Over the years, Gerald Chan Sieg had won numerous poetry awards locally and nationally. She had held just about every office in the Poetry Society, from Corresponding Secretary to President to the Executive Board Member. In 2002, The Poetry Society of Georgia honored her with the publication of The Far Journey in its Chapbook Series. “The Sad Lady” is written from the perspective of a mother lamenting the separation, or perhaps death, of her little boy. It can also be interpreted as the mothers back in China missing their sons far away in America:

In an Eastern garden

Where the water lilies float

Sits the fair lady

In a jade-embroidered coat:

And tiny shoes of red,

Jewels on her fingers,

And jewels on her head.

This is the song she sings,

While the moonlit flowers sway

To the sobbing of the lute,

Which her fingers ever play:

“Sweeter than honey made by the bee,

Pretty one.

Little Pearl-boy was stolen from me . . .

I’m alone.

Little Pearl-boy is so far away.

He’s asleep

In the cold arms of the flower fay . . .

And I weep.”

So the sad lady sings

Where the water lilies float,

And in her eyes are tears,

Though she wears a ‘broidered coat,

A jade-embroidered coat,

And tiny shoes of red,

Jewels on her fingers,

And jewels on her head.2

Fig. 3. The cover of Sieg’s book The Far Journey.

Another one of Sieg’s early poems is “Laundryman,” published in 1934, which describes the loneliness of early Chinese immigrants:

If I could hear once more

The call of dark winged birds across the fields

Of rice and slim young bamboo,

If I could see once more

A crane with yellow legs so straight

Among cool water grasses,

If I could touch again

Her hands whose fingers in the sleeve of scarlet

Are softly curled and gentle,

My soul would be content,

O gods,

To iron away eternity.3

Sieg’s depiction may have a lot to do with her father’s early involvement in Savannah’s laundry business. According to George B. Pruden, Jr., an East Asian History Professor at Armstrong State College (now retired), that after “trying without success to operate a farm and a restaurant,” Robert Chung Chan “was taken in as a partner of Willie Chin & Co., a Chinese laundry.”4 This might not have been the best outcome for the father, but it must have allowed young Geraldine to witness life in a hand-operated laundry. Many of Savannah’s downtown businesses, including those hand-operated laundry shops like the one Sieg’s father had, were very close to Savannah River, which provided the perfect setting for the scene described in the poem “Laundryman.” Many who worked in these laundry shops were Chinese immigrant bachelors. So after a long day toiling in the hot laundry shops, they would go to the river bank in the evenings, watching the ships go by, sending their thoughts home with the departing ships, thinking of families back in China.

In “The Chinese Children,” Sieg perhaps envisioned a childhood that is carefree, devoid of racial tensions, though the setting of the poem seems to be China, as the River Pearl is a famous river in Guangdong, the region where her father and most of the early Chinese immigrants came from. Though Robert Chung Chan was never able to go back home to visit, he would often tell his children about his hometown and his own childhood. Sieg told Pruden in 1983 that while growing up, just like the African Americans, Savannah’s Chinese children were not allowed to go to white public schools. This did not change until the year she started junior

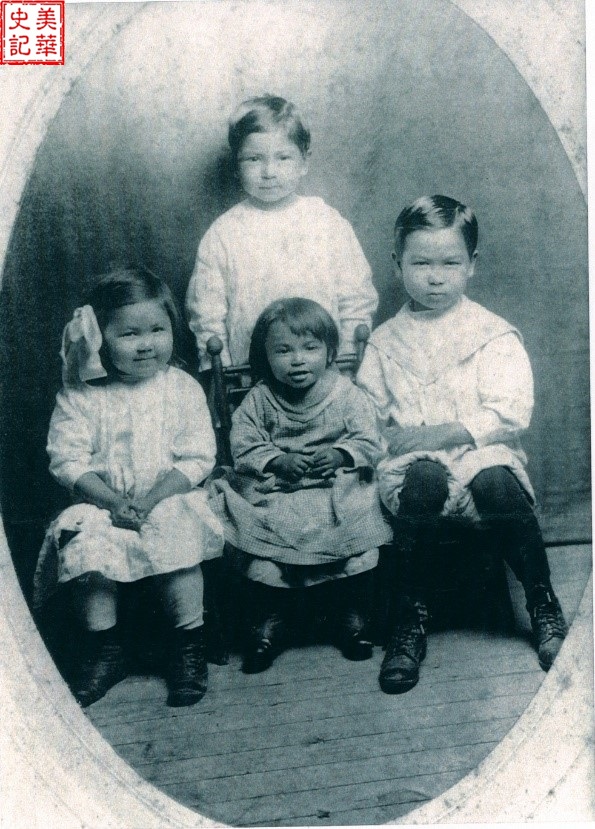

Fig. 4. Sieg, on the left, with her siblings. Used with permission.

Sieg and her siblings’ education was “provided by private teachers or in private schools.”5 Later in life, Sieg told Jane Fishman, who interviewed her on her 94th birthday, “‘I was a little Chinese girl who never associated with the white people,’ she says with just enough of a grin to make you wonder if that’s the truth.”6 The poem “The Chinese Children” depicts how a happy childhood should be:

Three small boys and one small girl

lived in a house on the River Pearl.

One small girl and three small boys

that had such very charming toys.

Stilts on which they walked so tall

that they could see above the wall.

A little junk to sail the pool

where lily leaves lay green and cool,

And where the golden fins below

went slowly gleamming to and fro.

A monkey climbing on a string

a jeweled bird that used to sing.

Some firecrackers red and bright

and rockets shooting out of sight.

Oh, what fascinating toys

for one small girl and three small boys!7

A lifelong Savannah resident, Sieg loved the life style of the low country and its southern charm. Depicting the beauty of Savannah and low country, Sieg writes in “A Gull Speaks” (1982):

This river front is home.

There busy wharfs and roofs and trees,

these cobbled walls and walks.

Where else would a bird find

life so varied?

. . . . . .8

Legends have it that Sieg and her late husband Edward A. Sieg (1907-1969) are partners in life. In “To the Wind,” Sieg, confessing the love and loss of her husband, she memorialized him with these touching words:

Wind, do you never

as you blow over,

those unknown peaks,

catch a glimpse of him

on some high crag?

For he was a rover

of heights, a lover

of rocks and cliffs,

where few have climbed

to lean on the cold

with space for cover.

Wind, should you hover

above him ever,

speak my name.

Say I am lonely.

Say I remember.

Say that I wait.9

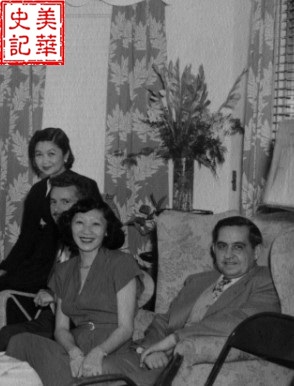

Fig. 5. Sieg with her husband Edward in 1950 (the couple on the left).

Sieg could be said to be an early feminist. She was an independent thinker and never let the fact that she was born a girl limit her potential. She famously explained her male sounding first name. Christened as Geraldine at birth, Sieg “simply hated” that name and later shortened it to Gerald, because “I knew early on that boys were considered better than girls, so if I couldn’t be a boy, I’d at least have a boy’s name.”10 In her poem “Eve,” published in 1997, Sieg pinpointed the roots of gender wars. She made it perfectly clear who should take the blame for the animosity and mistrust between men and women:

Yes, Adam,

I am sad: but not because our garden gate

is closed to us,

and we shall never hear again

the small birds singing words

we understand,

or comb again

the lion’s golden hair,

or lie together

on our couch of petals

watching the stars go up

the stairs of night,

so close we almost touched them.

No, Adam,

I am sad

because when Father called us

in that voice

he has never used before,

and we came to him

cringing and in shame,

you let me take the blame.11

“Portrait: Osteoporosis” (1989), one of Sieg’s favorites, peeps into the apprehensions of sickness and old age. Yet, Sieg never gave up on life or writing. I was fortunate enough to get to know Sieg in her waning years and saw how she carried herself with dignity and grace. I moved to Savannah in 1996 and joined the Chinese Benevolent Association the next year. I recall at our monthly meetings, Sieg, who was in her late 80s then, insisted on everyone calling her G.G. Elegantly dressed, straight-backed, she would walk up to every new member with a pen and little notebook in hand, and introduce herself. Then she would ask for their names and inquire about their life. She would take notes on her little notebook, as if she were collecting new materials for her poetry, which she may very well be. I remember visiting her at the Azalealand Nursing Home in May 2003 when I was preparing for a photography exhibition, which featured seven early Savannah Chinese immigrant families, including Sieg’s. She graciously shared with me some of her family’s photos and answered all my questions about her family’s experience in Savannah. She even gave me an autographed copy of her newly reprinted poetry collection, The Far Journey. Mark Murphy, a Savannah physician and writer, who is married to Sieg’s granddaughter Daphne, describes his first meeting with Sieg when he was 15, and his poem “Transitions” was first runner-up in a poetry contest sponsored by the Poetry Society of Georgia: “Stylishly attired in red, with perfectly manicured nails and hair pulled up tightly into a bun, G.G. moved with the subtle grace and erect posture of a ballerina. She was imposing, despite her slight build.”12 I find it hard to reconcile the image I have of Sieg with the ones in this poem:

If a dry bough long fallen

should stand and slowly move

its stiffened curvature

along the street,

it would give an idea

of her desiccation,

her crumbing hollows.

If a praying mantis

should don a dress

with a Victoria neckband,

it would give an idea,

of her wispy going

on her errands,

her little head out front,

brittle fingers clutching

the handbag handle.13

Sieg’s Other Writings

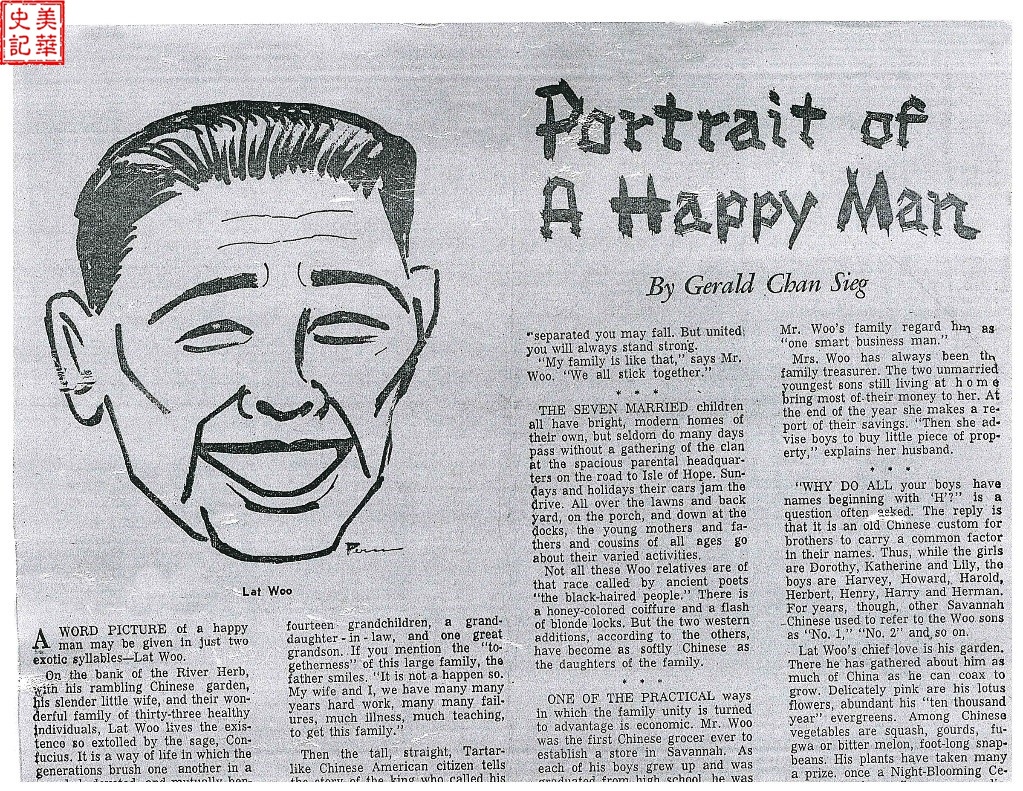

In addition to writing poetry, Gerald Chan Sieg was a frequent contributor to the local newspapers: Savannah Morning News and Savannah Evening Press (the two merged in 1969 as Savannah Morning News). She used her pen to promote Chinese immigrants, Chinese cultural heritage, and called attention to their many valuable contributions to the Savannah community. In the November 11, 1958 issue of Savannah Morning News Magazine, Sieg’s article “Portrait of A Happy Man” was featured. In the article, Sieg profiled Lat Woo¾who co-founded Chinese

Benevolent Association with Sieg’s father Robert Chung Chan and Charlie Jung in 1945¾as the “first Chinese grocer ever to establish a store in Savannah”: “On the bank of the River Herb, with his rambling Chinese garden, his slender little wife, and their wonderful family of thirty-three healthy individuals, Lat Woo lives the existence so extolled by the sage, Confucius. It is a way of life in which the generations brush one another in a rounded, devoted, and mutually beneficent communication.”14

Fig. 6. Sieg’s article “Portrait of A Happy Man” in Savannah Morning News Magazine, November 30, 1958.

Another example can be seen in Sieg’s article marking the Chinese New Year, Year of Rat, January 28, 1960. The title of the article has simply two Chinese characters 鼠年 (Rat Year). Here, she informed the readers how Year of Mouse, as she called it, was celebrated: “With gongs and parades, with feasts and ceremonies, wherever Chinese gathered, the Year of the Pig ended Thursday and the New Year is being welcomed this weekend. Celebrations all over the world will continue through today.”15

As a lifelong member of The Poetry Society of Georgia, Sieg would never have missed an opportunity to promote the society’s events. In October 1964, when Pearl S. Buck, the Nobel Prize laureate in literature, came to Savannah to kick off her foundation’s annual campaign with a public dance at the DeSoto, Sieg penned an article “Poetry Society Pays Tribute to Pearl Buck” published in October 20, 1964 issue of Savannah Evening Press. Sieg’s article focused on Mrs. Buck’s speech at the fall meeting of the Poetry Society of Georgia on October 19 where she touched on the world of the writer: “Writing a book . . . is like the making of a star. It is only a movement in the mind. Then just as particles whirl and collect other particles” in forming a star or a planet, ideas collect in a “sort of magnetism . . . in a process almost apart from ourselves.”17

It is worth noting that during Mrs. Buck’s visit to Savannah, whose main mission was to raise money for “a fund she established to aid half-American children in foreign countries, particularly in Asian,”18 the local Chinese community came out in full force to embrace the famed author, who put China on the world map with her books based on her early days living in China, such as The Good Earth (1931) and Dragon Seed (1942). They threw a dinner in her honor and presented her foundation with a $130 check. You guessed it: Sieg proudly represented her community at the dinner.

Fig. 7. Sieg, first on the left, attended the dinner Chinese community in Savannah given in Pearl S. Buck’s honor, October 19, 1964. Chinese Benevolent Association file photo.

Sieg’s Legacy

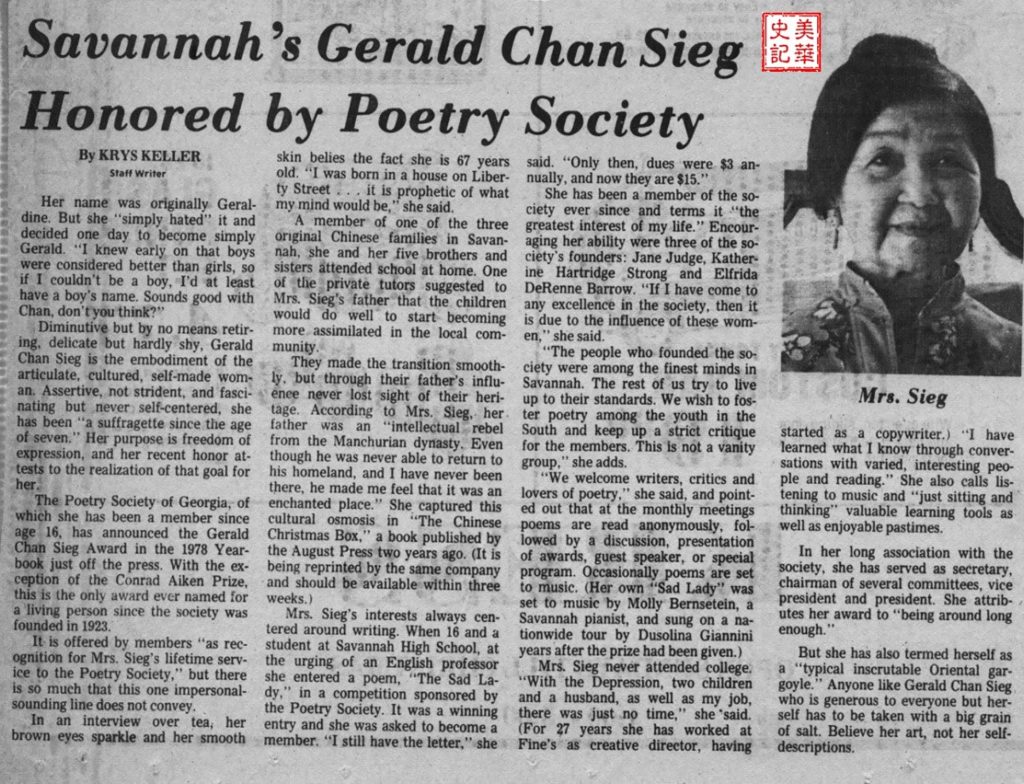

The Poetry Society of Georgia knew they had a rare talent in Sieg and honored her by establishing a Gerald Chan Sieg Award in 1978. In the article “Savannah’s Gerald Sieg Honored by Poetry Society,” Krys Keller writes, “With the exception of the Conrad Aiken Prize, this is the only award ever named for a living person since the society was founded in 1923.”19 Thedescription of Sieg in the article captures her endearing quality and enduring charm: “Diminutive but by no means retiring, delicate but hardly shy, Gerald Chan Sieg is the embodiment of the articulate, cultured, self-made woman. Assertive, not strident, and fascinating but never self-centered, she has been ‘a suffragette since the age of seven.’ Her purpose is freedom of expression, and her recent honor attests to the realization of that goal for her.”20

Fig. 8. Keller’s article in Savannah Morning News-Press, November 5, 1978.

In the introduction to Sieg’s The Far Journey, Hugh Pendexter III, the editor of The Poetry Society of Georgia Chapbook Series, included his own poem “Gerald Chan Sieg” at her request. I leave it with you to remember Sieg, a laundryman’s daughter, Savannah’s famous poet:

Delicate, the porcelain receives

A steaming gush upon the pungent leaves;

Among her glazed chrysanthemums of gold

The guardian dragon’s crimson coils enfold

Translucent rondure of her polished clay

And rear its spouting head. Beguiling spray

Of jasmine scented mist she wafts to woo

Our taste to oolong’s dark astringent brew.21

References:

1. Derek Smith, “100 Years Ago: Our ‘Whirlwind of Fire’” in Savannah Evening Press, Thursday, April 6, 1989, p. 15.

2. Gerald Chan Sieg, The Far Journey (The Poetry Society of Georgia Chapbook Series, Number Two): 6.

3. Ibid., 11.

4. George B Pruden, Jr., “History of the Chinese in Savannah, Georgia” in Studies in the Social Sciences, Vol. 22, (1983): 13-25: 17.

5. Ibid., 21.

6. Jane Fishman, “A born poet reflects on growing up Chinese” in Savannah Morning News, date unknown.

7. Sieg, The Far Journey, 26.

8. Ibid., 32.

9. Ibid., 55.

10. Pruden, 21.

11. Sieg, The Far Journey, 78.

12. Mark Murphy, “Goodbye to Robert Earl, the last of the Chan clan, who lived the American dream,” March 13, 2016. https://www.savannahnow.com/column/2016-03-13/mark-murphy-goodbye-robert-earl-last-chan-clan-who-lived-american-dream

13. Sieg, The Far Journey, 84.

14. Gerald Chan Sieg, “Portrait of A Happy Man” in Savannah Morning News Magazine, November 11, 1958.

15. Gerald Chan Sieg, “鼠年” in Savannah Morning News Magazine, January 31, 1960.

16. Ibid.

17. G.C. Sieg, “Poetry Society Pays Tribute to Pearl Buck” in Savannah Evening Press, October 20, 1964.

18. “Novelist Buck Arrives” in Savannah Evening Press, October 20, 1964.

19. Krys Keller, “Savannah’s Gerald Sieg Honored by Poetry Society” in Savannah Morning News-Press, November 5, 1978.

20. Ibid.

21. Hugh Pendexter III, “Gerald Chan Sieg” in Sieg’s The Far Journey, 5.