Author: Xi Luo

Translator: Ella N. Wu

Guide:

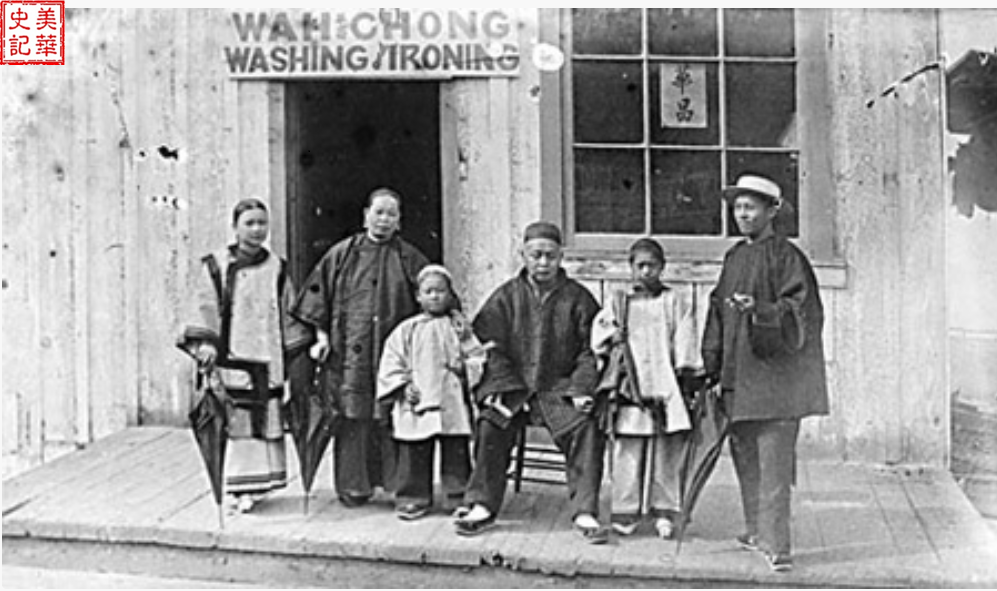

The Chinese are hardworking and intelligent, but why were the early Chinese immigrants in the United States subject to the laundry industry? For the first wave of Chinese immigrants to the U.S. in the mid-19th century, the laundry industry became a secure way for Chinese immigrants to support themselves in American society. By the 1870s, Chinese-run laundries had opened up in the streets of American cities, integrating into the daily lives of local residents, and the image of the laundry men had thus become an ethnic symbol for the Chinese in American society.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

– Emma. Lazarus’s “The New Giant” is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty

“Gold is not in the mountains of California, but in the mountains of dirty clothes.”

– John Zheng, “Chinese Laundry”

Chinese Laundry Business, from havenlight.com

What kind of job is laundry?

How does the job of doing laundry come into high demand? For centuries, laundry and ironing have been done at home—a job relegated to women, whether they be servants, mothers or wives. Doing the laundry is a tiresome, tedious job. It was not until the water supply system became available that washing clothes could be performed at home. Before this invention, the water for cleaning first had to be heated to a boil with fire. Then, the clothes needed to be soaked, rubbed repeatedly by hand to remove stains, and finally hand-wrung, to be hung on the rope outside to dry. This painstaking job takes an entire day and requires another day to iron the dried clothes.

Thus, there is no doubt that laundry is not an exciting task. In the nineteenth century, many people believed that the bacteria around them could cause disease, so wearing clean clothes and taking regular baths became a well-regarded daily ritual. Dressing neatly also became a sign of a higher social status. Cleanliness, like piety, was a virtue, which is why the laundry industry rose exponentially during this era.

On the western border of the United States, there were very few women who could do laundry, and the clothes and linens that required washing sometimes needed to be shipped to Hawaii for cleaning, which was an enormous waste of time and money. Doing laundry in cramped apartments in densely populated eastern cities was also a headache. It was clear that both the east and west struggled to do laundry comfortably, which opened up business for laundry.

For the early Chinese in America, laundry work is said to have been their ideal occupation. After the gold rush in California in 1849, a large number of Chinese migrated to the United States. When the gold mines began dwindling and the railroad line across the North American continent was completed in 1869, California began enacting a series of laws and tax provisions that discriminated against Chinese immigrants in the mid-19th century. Coupled with that was the rising wave of violence by white laborers. It would not be easy for the Chinese to survive in a country whose political and social institutions fought against them. Furthermore, the laundry industry was unattractive to whites: “In the eyes of whites, Chinese laundry workers deal with dirty sewage and unpleasant smells.” (1) However, for the Chinese immigrants who didn’t know English, this profession was suitable, requiring only a small investment of about $500 for start-up capital. Thus, the laundry industry allowed these immigrants to secure their own livelihoods.

What is the work of the laundry industry?

“Laundry is a grueling sort of work that requires 10-16 hours of work per day. The steaming water bubbles loudly in the kettles, and a hot iron sits on the stove. The family who works at laundry navigates the slippery ground with an eight-pound iron. Clothes need to be soaked, brushed, washed, scrubbed, dried, ironed and leveled, and the whole process must be done by hand. The job also includes bleaching removable collars, sleeves and chest liners, which requires patience, meticulousness and skill. What’s more, only high-quality service can satisfy customers. It’s a profession that works long hours and earns very little. Laundry workers typically earn $25 a month (the average daily wage for a Chinese worker building the transcontinental railroad is $1-3), seven days a week, and the Chinese laundries are open all year round. But they pride themselves on having ‘adaptable’ stomachs that can withstand not eating for one or two days. However, this is not true, and many laundry workers were struck by varicose veins and puffiness in the calves, a health implication as a result of the job. For most laundry workers, their daily routine consisted of working, eating, sleeping, and working again nonstop with no time for leisure. (2).

Therefore, although laundry is a dull, toiling job, for many early Chinese immigrants it was the only way to survive in a land where social, economic and political conditions worked against them.

Chinese laundries and struggles in the rainy years

Chinese Laundry http://countercultures.net/design/portfolio-item/the-hand-laundry-a-chinese-legacy-2/

The Chinese Laundry in Brooking, New York, is from rmichelson.com

IN 1851, Wah Lee opened his first laundry in San Francisco. The laundry was a small, rented property, with simple sign boards that read “wash and iron.” A few weeks after the laundry opened, business was booming and in short supply, so Lee soon expanded to 20 laundries, working three shifts a day.

The history of the Chinese Laundry continued from the middle of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, and in this stormy 100-year period, the laundry became the haven where Chinese people sought to survive in American society.

In this century, many historical events unfolded, the most important of which relating to the uncertain fate of Chinese Americans in the United States: the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was approved by both houses of Congress, was the first and only race-oriented law in the United States, which was designed to prevent Chinese migrants from entering the United States and to make it impossible for the Chinese already in the United States to obtain citizenship. The law lasted 61 years and was not repealed until 1943. Before and after the law came into effect, there were many discriminatory provisions levied against the Chinese—some which led to violence and massacres. For example:

The massacre in Los Angeles, California, on October 24, 1817. 500 white and Hispanic thugs broke into Chinatown, robbing, burning and killing about 20 Chinese, some of whom had their bodies hung and their fingers cut off. However, no justice was served as the mob was dismissed for insufficient evidence.

In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court disputed the case of Dred Scott. At the instigation of Dred Scott Decision, American nativists prevented Chinese from obtaining citizenship and called for their deportation.

In 1858, California began to prohibit Chinese from entering the state, and imposed discriminatory taxes on them. These laws were not repealed until twenty years later.

As a result of inaction by the U.S. government, race-related clashes and fights broke out on September 2, 1885, between white and Chinese miners in Stone Springs, Wyoming. The white miners claimed that the Chinese robbed Americans of their jobs, resulting in the massacre of twenty-eight Chinese, the dismemberment of some and the burning of others alive. But the end result was that the perpetrators were released for lack of evidence and the incident was over. Justice was not served.

In the 1870s, the Chinese living in the United States still faced serious discrimination. Beginning with the Burlingame-Seward Treaty of 1868 and the Page Law of 1875, which culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a series of decrees were implemented that severely restricted Chinese immigration to the United States. Chinese men were not allowed to enter the country to work, and most Chinese women were considered prostitutes, so were turned away as well.

On February 6-9, 1886, 300 Chinese were forcibly removed from Chinatown after an incident in Seattle, where they were driven onto a boat, forced to buy tickets for their removal, while racists jeered to them ashore, “Goodbye!”

Chinese laundry work was also criticized because most of the Chinese workers who performed this low-income, high-intensity work, were men, and this was thought to have robbed white women of their jobs and forced some white women into prostitution.

When non-Chinese workers began entering the laundry industry, Chinese laundries became targets to local governments, in an effort to rid the Chinese population from working in the industry to make way for white workers.

“In 1880, 95 percent of San Francisco’s 320 laundry businesses were operating in wooden buildings. On 26 May and 28 July 1880, legislators adopted Regulations 1569 and 1587, respectively, requiring owners of laundry businesses in wooden buildings to obtain permits. Those who refuse to comply would be fined $1,000, or up to six months in prison, or both. Two-thirds of the local laundries were run by Chinese, but none were authorized. However, only one of the non-Chinese laundry businesses was considered unauthorized.”

In an effort to resist this discriminatory regulation, the Chinese laundry business owner Yi He, who had run his business for 22 years, and 150 other Chinese laundry business owners who had also encountered the same discriminatory law, decided to ignore the regulations and operate as usual, which resulted in all of the workers’ arrests. Yihe operated a laundry business that had been inspected by the fire department and the public health department, who stated that “all the housing standards for running a laundry are safe.” However, the municipality refused to issue him a license to operate. So Yi He took Sheriff Hawkins, who arrested him, to court, asking the California Supreme Court to issue a habeas corpus and correct the city’s misdeeds. Yi He argued for a habeas corpus on the grounds that his arrest violated the California Constitution, the U.S. Federal Constitution, and the 1880 Sino-American Treaty. But the California Supreme Court rejected these charges. Meanwhile, another laundry business owner filed a similar lawsuit in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of California. In the end, the case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

After the victory of the Civil War, the United States passed three constitutional amendments, the 14th Amendment, which came into force in 1868, known as the Equal Protection Clause, which provides that states “shall not, within their scope, deny any equal protection under the law”. The amendment was originally intended to protect free Black people from discrimination, but Yi He’s lawsuit to defend his laundry business expanded the narrow interpretation of the amendment. The equal protection of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution applies to all those living in the U.S., including non-citizens. The “laundry clause” laid down by the authorities, which hides behind a false neutrality, was, in reality, enforced specifically to discriminate against the Chinese, which effectively negates equal legal protections for the Chinese. In the end, the weapons of discriminatory law were defeated in the laundry defense battle. During the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the laundry lawsuit became an important cornerstone of U.S. equal protection laws in the mid-1920s and a classic case for discussing equal protection provisions of the Constitution.

After the Great Depression after 1929, laundry work became a popular job, and Chinese workers were once again the target of white hatred. Chinese Americans were treated unfairly, but as individuals they had little ability, time and resources to fight back effectively. In the 1930s, before the Great Depression, there were about 3,550 Chinese laundries in New York City. In 1933, the New York City Council enacted a law that allowed only U.S. citizens to own laundry shops, and federal law suspended the naturalization process for all Chinese immigrants. Thousands of laundry workers gathered in New York to form the Chinese Laundry Workers Alliance to fight racism. The organization’s actions against this discrimination, which included conditions such as mandatory citizenship and high licensing fees for specifically Chinese-run laundries, successfully fought unequal legislation against the Chinese and enabled thousands of Chinese laundry shops to make ends meet.

Chinese laundry workers who are stigmatized in the eyes of racists

Stereotypes of the Chinese in America included vile depictions of the first generation of Chinese immigrants in American society, which was featured in mainstream media, literature, the Internet, film and television, and music. During the 20th century, only one in four Chinese immigrant men in the United States worked in the laundry industry; before, about 90% of San Francisco’s laundries were Chinese. The image of Chinese laundry workers in the U.S. is deeply rooted in American culture, even today, and with that, negative stereotypes based in race still hold enormous power over people. In order to rid these negative stereotypes, we as citizens must work diligently to reclaim the narrative of Chinese laundry workers.

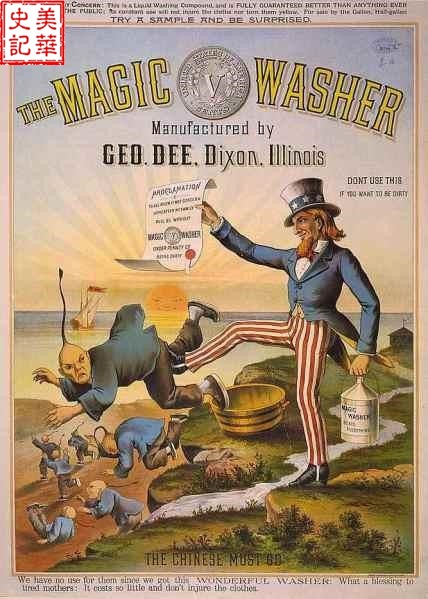

In the 1870s and 1990s, advertising cards were a popular way to sell products. The image of a Chinese laundry worker appeared as caricatures in all product promotions related to detergents, dryers, and soaps. Of course, many of the depictions of Chinese laundry workers were extremely racist. Racists often turn the Face of a Chinese Laundryman into an image of a man with braids, squinted eyes, incompetence, masculinity, sexual hunger, and threats to white women. Some comics drew caricatures of the Chinese language and clothing. White competitors of Chinese laundry workers also played a key role in the stereotyped Chinese society. Some European immigrant workers, union bosses and politicians deliberately spread malicious rumors about the Chinese, exacerbating racial hatred against the marginalized group.

The image of a Chinese laundry worker by Facebook https://chineselaundry.wordpress.com/page/10/

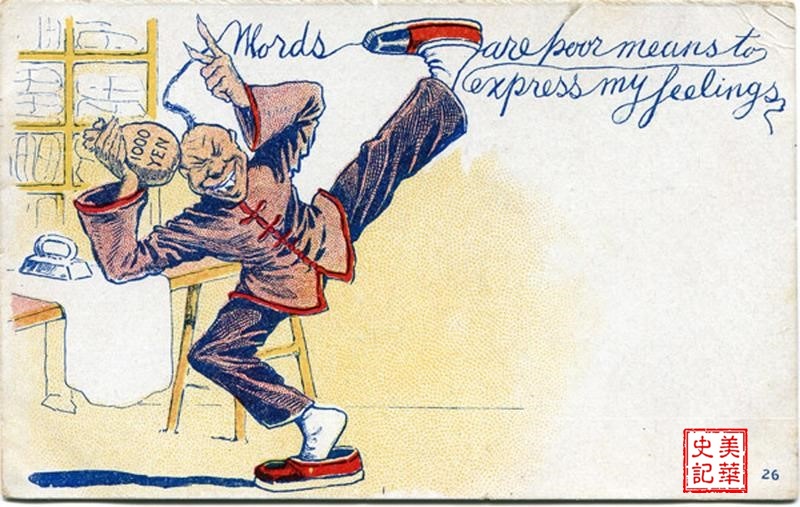

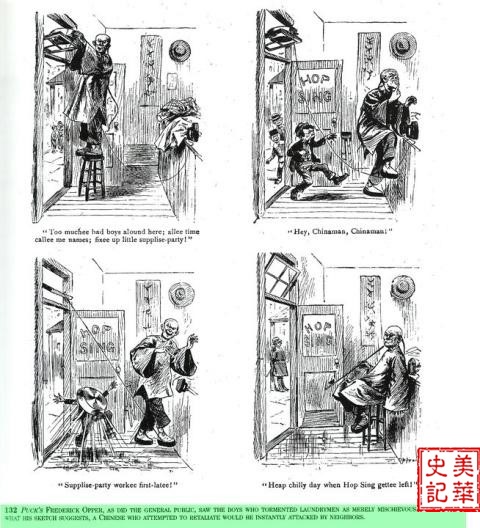

Chinese laundry workers were not only subjected to unequal laws, physical violence, and sometimes even children who played pranks on them, throwing mud on clothes that had been dried and hung outside, but corporations were spreading hate and propaganda against them.

The following cartoon is named “Chinese Laundry Man’s Fantasy of Fighting Back?” Current affairs commentators sometimes sympathize with the Chinese, such as the following FREDERIC OPPER cartoon. Although the action of the Chinese laundryman in this cartoon can be considered a “sweet counterattack” and the basin can be replaced with a frying pan, such a scenario is often a fantasy in real life.

The fantasy of fighting back https://chineselaundry.wordpress.com/page/10/

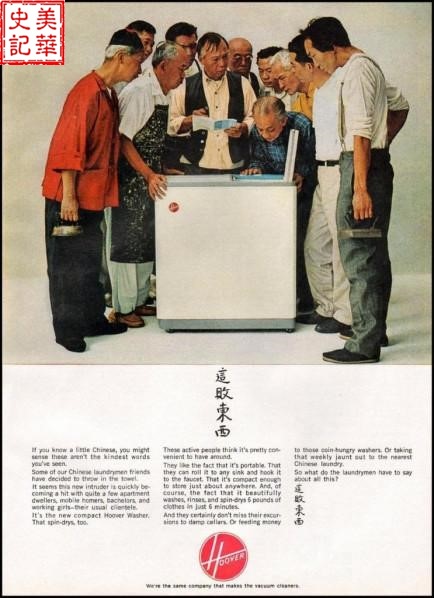

Earlier racial discrimination against Chinese was public, and sometimes violence against people and property occurred. Although laundry is not a profession that Chinese yearn for, racists used it to stigmatize all Chinese who do it to make a living. The cartoon below is a racially charged washing machine ad that shows that Chinese (human laundry machines) should be kicked out and replaced by washing machines.

Racist laundry ad https://chineselaundry.wordpress.com/page/10/

After World War II, American society became more and more accepting of Chinese because of China’s ally ship during the war and the repeal of the Exclusion Act, but some racists still targeted the Chinese. In an advertisement for a HOOVER washing machine, a group of laundry experts (Chinese laundry workers) are depicted curiously staring at the washing machine. The advertisement tells consumers that in the face-off between washing machines and Chinese laundry workers, Chinese laundry workers would become outdated, useless tools that could not keep up with the trends.

Even as recent as 2008, a racially-charged news story about Beijing’s inclusion of laundry in the Games was released, making racist jokes about Chinese people having an unfair advantage in the laundry sport category.

The news article is from https://chineselaundry.wordpress.com/page/10/

According to the latest Asia-Pacific data released by the U.S. Federal Census Bureau in 2017, the median household income of Chinese-Americans continues to lead other ethnic groups by more than $76,000, and Asians are the most educated ethnic group in the United States. Yet the status of an ethnic group in the United States is almost directly determined by its portrayal in the media and its subsequent influence on society’s view of the group. The Chinese are the weakest in this respect. In a democracy, whoever can control the media and use it to guide the public’s opinions, whoever can influence people’s votes to support favorable policies and candidates—those are the people who succeed in the United States. Mere income level does not define the acceptance and prosperity of a race of people in America. Now think: What is the image of Chinese people in the US today? Has the US shaken off the stereotype of the Chinese working the laundry? Has the US supported any political leader who can represent and support Chinese-Americans? Does the US amplify the voices of Chinese stars, athletes, and artists in an effort to shape a new image of the Chinese in American society?

Life of a Laundry Worker

In order to gain an in-depth understanding of the Chinese laundry career, it is more productive to focus on an individual rather than attempt to conceptualize the entirety of Chinese laundry workers. Although each individual experience is different, many share similar experiences during the migration to the US. Life in the laundry industry undoubtedly reflects the collective memory of many early Chinese immigrants who had no choice but to live in a small laundry, suffering from the separation from their families on the other side of the ocean and struggling to survive in a racially charged environment.

Due to a careful search for descendants of Chinese immigrants, we found a story of a laundry shop called Yee Jock Leong. A Chinese man named Yu Zuo Liang was born in San Francisco in 1884, but his father brought him back to China at an early age. When he turned nineteen, Yu returned to the United States and two years later returned to China to marry. In 1908, Yu left his wife and children in China and returned to the United States alone. In 1914, he opened his own laundry in Irwin, Pennsylvania, and re-married, this time to a Chinese and Mexican descendant in 1915. The couple then moved to Dayton, Ohio, where they ran a laundry shop, rarely making ends meet during the Great Depression. Later, Yu left his wife in Dayton to continue running the laundry shop while he traveled to Chicago on his own, attempting to find a job. However, he was unsuccessful and eventually returned to work his laundry business in Dayton until he died of tuberculosis in 1936 at the age of 52.

The laundry worker named Yu Zuo Liang https://chineselaundry.wordpress.com/tag/yee-jock-leong/

Yu’s life story is a typical one for many early Chinese immigrants, which was marked by suffering and hardship. Yu’s experience of traveling across the Pacific Ocean reflected a new identity: that of a wanderer. Although historically the Chinese have never considered themselves inferior, when they traveled to the US, Chinese immigrants accepted a second class working status. They had to find a place of belonging in a new land, living short lives due to the lack of aid in the face of hardship. Even some Chinese-Americans, although born in the United States, faced hostility from the outside world. This forced them to communicate with their homeland, and the support from China remained the backbone of this generation of Chinese-Americans in an unfriendly new world. Also, due to the historical background of the Chinese Exclusion Act , the separation of Yu and his wife was common among the Chinese community at that time. So in order to support family back home, many young Chinese-American men had to send regular remittances.

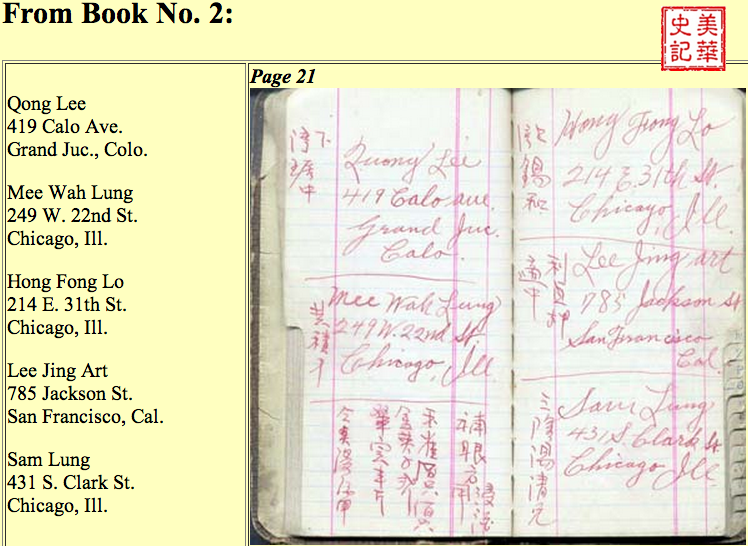

The most notable of the remains of the Chinese-Americans of the past are the three address books, which contain records of the names and addresses of more than 100 people. The books document many Chinese living in Ohio, working as business partners, suppliers, button sellers, plumbers, and so on. Although not aware of their kinship, it can be seen that Yu still had connections with those in the Chinese community.

The remaining address books http://fuzzo.com/genealogy/YeeJockLeong/addressbook2/YeeJockLeongBook2D.htm

In the face of these yellowing photographs, letters, and records that have been lost and replaced over time, we can better understand the position of John Zheng, author of The Chinese Laundry Business. He states that despite their inhuman treatment, Chinese laundry workers did not complain about their inferior status in American society and did not view themselves as victims, but rather as a group of great survivors.

While many white people in the US were racist, there were still some who learned to become accepting of those of other races. Due to extensive research online, the author was able to find out about the story of a white child and a Chinese laundry child. David Farside recalled his invitation to a Chinese family dinner at the Corner Laundry when he was eight years old, and more than a decade later, he still has a wonderful experience of that night. Here’s the URL of his full log: https://davidfarside.wordpress.com/tag/chinese-laundry/

In the article he wrote:

“There is a Chinese laundry shop on the same street not far from my home. When we were children, we always laughed at their bad English, their dress, their eating habits, the crowded room in the sweaty workroom.

But when World War II struck in 1944, almost all of them lost their jobs, and only the Chinese laundry business survived. Every morning, whether it was windy or rainy, a Chinese man pushed a huge iron basket cart into the city center to collect dirty clothes from businesses, government departments and restaurants. At dusk, he pushed the same cart to clean and iron tablecloths, work uniforms, and linens. Then, the man would trek back with the clean clothes, in exchange for payment. Week after week, day after day. Politicians also liked the Chinese laundry and its door-to-door washing, which was a most satisfactory service. ”

Eight-year-old American boy David Farside invited a Chinese girl named Meiyi to a birthday party. Meiyi was the only child without a gift, and David thought it was probably because her family was poor. But towards the end of the party, Meiyi gave David a note that said she would invite him to her house for dinner. David’s mother was afraid it would be unsafe to let her son go, but David insisted on going. At the laundry shop, David was welcomed happily and he walked through the “clothes-filled maze, with irons and laundry boards at the back of the shop.” ”

In the backyard, he saw a tin house, like an old garage. As soon as he walked into the tin house, he found “the whole family sitting on the ground, surrounded by a round teak table turntable filled with food.” Together, they sang a happy birthday song to David in Chinese. David sat in the guest seat and began to eat. He did not recognize any of the food except for rice. But 65 years later, David still recalled the taste of the night’s exquisite food.

After dinner, David joined the family’s cultural and recreational activities, which, though unfamiliar to him, were fascinating. Back home, David told his father that he would not be surprised if the Chinese could make a lot of money and get a high level of education, because they were hardworking and friendly. His father listened for a moment and said, “David, the truth of things is sometimes not what it looks like, and I hope you will always remember what you learned tonight from the Chinese laundry shop.” Thus, the experience of the Chinese laundry was the most precious gift David had ever received.

David finally wrote in his own journal: “It took me ten years to digest the experience of that cold November night in a Chinese laundry shop. From this I learned to be diligent, kind, and humble about wealth. I learned not to judge people easily by their clothes, skin color or accent, because after all, they are struggling to communicate with us in a language unfamiliar to them.”

1920 California Family Laundry chineseancestor.org

From the corner laundry shop to the mainstream

“As long as there is a person who is willing to work long and hard to wash dirty clothes, the laundry business will undoubtedly have promising business prospects. This exhausting job also binds men to their homes, with little energy to gamble, which is common in Chinatown. Furthermore, the job can generate a lot of money, and laundry work makes enough money to buy a $55,000 hotel.” (Note 3)

In the early nineteenth century, Chinese laundries played a vital role in the survival of Chinese-American society. Between 1890 and 1900, the number of Chinese laundries peaked in major cities, while Chinese restaurants opened up a new possibility for Chinese to start their own businesses. In 1896, US National News reported that a Chinese governor had praised a Chinese dish called “chop suey” in New York, which created a booming popularity of Chinese food from non-Chinese people. However, Chinese restaurants did not gradually take over Chinese laundries until the 1920s. For example, the Chinese in Dallas began switching from laundry businesses to restaurants from 1875 to 1940. In addition, many Chinese laundry shops were facing fierce competition with white steam-powered laundromats.

A hundred years ago, Chinese laundries were everywhere, in almost all cities, large and small, in the United States and Canada. Today, washing machines and dryers have become staples in thousands of households, and people without washing machines can go to coin-operated laundries to do the job. In the 1950s and 1960s as the laundry industry died out, Chinese immigrants turned to new industries such as restaurants. However, the next generation of Chinese did not follow this tradition, and most of them were able to gain college education and enter various fields of occupation that had previously been restricted to Chinese people.

Among the descendants of the Chinese laundry workers is the legendary Wen Yingxing and his great-grandson, Ke Liren. Wen Yingxing, the first Chinese-American graduate to graduate from West Point in 1909, served as an Army general during the civil wars of China, and later immigrated to the United States, where he opened a laundry shop. In 2017, the 21-year-old Ke LiRen also became a graduate of West Point, following the family’s legacy.

Ke Liren chinaqw.com in front of his great-grandfather’s tomb

Anna May Wong was the first Chinese Hollywood star to emerge from the Chinese laundry business. She was a third-generation immigrant with a long, successful career. Her acting career spans silent films, audio, television, stage and radio dramas, and she has a place on the Hollywood Walk of Fame alongside Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan.

Anna May Wong blog.sina.com.cn and m.lifeweek.com

When the Chinese came to the American continent, they were known as hard workers—digging in gold mines, building railways, developing farms in California, and then working in the laundry industry. It should be said that on the road to great power in the United States, the Chinese sweat and bled and paid the price of their lives. Chinese laundries are now history, and at the end of October 2016, the most successful and long standing Chinese laundry business in American history, Ching Lee, finally closed after 140 years of operation. This allowed Chinese society in the United States to enter a new age, leaving behind a period of sweaty, crowded laundry shops.

However, Chinese-Americans today must remember that without early Chinese immigrants who passed on the spirit of self-sacrifice, courage, skill, and perseverance, Chinese people today would not have achieved so much in American society. In fact, some international Chinese students would have been asked, “Is your father a laundry worker?” in an effort to mock Chinese-Americans’ humble beginnings. In order to counter this racist ideology, Wen YiDuo wrote “The Laundry Song,” which points out that “Jesus’ father was born as a carpenter,” showing that some of the most noble people in history came from humble beginnings and that it is not a cause for shame. Thus for Chinese-Americans, the road to success and prosperity is still a long one, but it is worth working and fighting for.

Citations:

1.2 Iris Chang, “The Chinese in America: A Narrative History”.

3. Graham Russell, “Anna May Wong: From Laundryman’s Daughter To Holly.”

4. Wenyi Duo “Laundry Song” https://baike.baidu.com/item/% E6%B4%97%E8%A1%A3%E6%AD%8C/2890831

5. All the pictures in the text are from the web.

Thank you so much for publishing this article. By informing the public about Chinese laundries, we are more knowledgeable about the history of Chinese integration into the United States and how they prevailed through racial discrimination in the workforce.

This was such an informative and well-written article. I appreciate all the hard work!

Thank you again!

-Mya

Two questions:

1. Do you know of any Chinese laundry business that existed in the Sierra Nevada’s sometime between 1848 (the start of the Gold Rush) and 1883 (the year after the Chinese Exclusion Act).

2. What was needed, other than capital investment, to start a Chinese Laundry. The washing was done all by hand, yes? Therefore, a freshwater source (stream) was needed? Plenty of that in the Sierras? But probably also people who wanted their clothes washed and had the money needed to pay someone else to do it? In SF, folks like that surely could be found. But in the Sierras during this time period?

Asking because I’m a high school US History teacher and have some students trying to find the answer online–to no avail.