—— The Life Story of Yan Phou Lee from the “Chinese Educational Mission” program

Author: Yuan Zhuang

Translator: Rosie Pingxin Zhou

Introduction

In the five decades that he lived in the United States, Yan Phou Lee participated in the establishment of the earliest Chinese school, introduced China and Chinese culture to the American people, and lobbied against the Chinese Exclusion Act. His life is the story of a brave and intelligent Chinese man who loved Western civilization and pursued Western idealism, and sadly suffered from insidious racism.

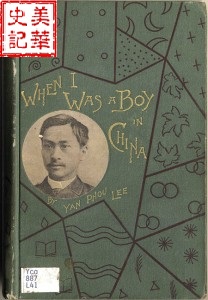

Picture 1: Yan Phou Lee in 1887 (1861-1938)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Yan Phou Lee, a child during the Qing Dynasty who studied and lived in the United States for more than 50 years, decided to return to China at the age of 65. On departure, Lee was asked by customs officials, “Of which country are you now a citizen or subject?”

“It is hard to say,” he replied. “I took out my first papers to become a citizen of this country but I never got my last papers on account of the amendment to the Exclusionary law preventing me.”

“Then you must be a citizen of China, is that right?”

“I presume so, or a citizen of no country at all.” 【1】

Lee graduated from Yale University in 1887 and was a writer, speaker, editor and reporter. He had two wives, both white, and four children. Through his groundbreaking book, When I was a boy in China, he became the first Asian-American author to publish in English in the United States.

Leaving the Homeland and Parting with Loved Ones Once Again

Lee was born in Xiangshan (or Fragrant Hills, now known as Zhongshan), Guangdong in 1861. His grandfather was the vice principal of a college, and his father ran a rental business of wedding sedan chairs. His father died when he was 12 years old. When he learned he was eligible to participate in the “Chinese Educational Mission” program, Lee “acceded without hesitation.” As he later wrote in his memoir, “The opportunity to go out and see the world is what I long for.”

In 1873, 12-year-old Yan Phou Lee (indicated as 13 years old on the Chinese version of Wikipedia’s “Chinese Educational Mission” program student list) and 29 others comprised the second group of the “Chinese Educational Mission” program. They boarded a ship in Shanghai, sailed to San Francisco via Yokohama, then traveled to Springfield, Massachusetts by train. Lee would later write wryly in his memoir that “Nothing occurred on our Eastward journey to mar the enjoyment of our first ride on the steamcars—excepting a train robbery, a consequent smashup of the engine, and the murder of the engineer.” He went on to describe a harrowing experience complete with gunfire, stolen gold bricks and luggage, robbers dressed as Indians who escaped on horseback, and more. “One phase of American civilization was thus indelibly fixed upon our minds,” Lee wrote. A newspaper at the time reported that a train was robbed in July of that year—by Jesse James—near Adair, Iowa; “Among the passengers were thirty Chinese students en route to Springfield, Massachusetts,” confirming Lee’s account. 【2】

Picture 2: The second cohort of students from the “Chinese Educational Mission” program.

Yan Phou Lee boarded in the home of a doctor named Henry Vaille in Springfield and attended Springfield Public Schools. When he arrived at the Springfield train station, Sarah, the doctor’s wife, greeted him with a hug and kiss – the first kiss he remembered since infancy. (Lee’s lack of memory of such gestures from his biological mother does not necessarily indicate a lack of love. Rather, as he stepped out of an environment of suppression, forbearance, subtlety and indifference, and integrated into American society for the first time, Sarah’s casual act of physical affection came as a shock to the young teenager.) Lee’s intelligence and understanding won Sarah’s love. As Sarah’s son later wrote about Yan Phou Lee in an August 28, 1884 article in the Buffalo Weekly Express, “Mother thought almost as much of him as of me.”

Lee maintained a close relationship with Sarah’s family and later chose their surname, “Vaille” , as the middle name of his son Clarence.

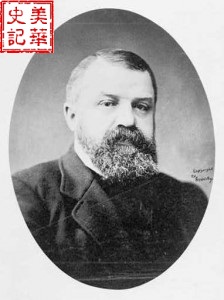

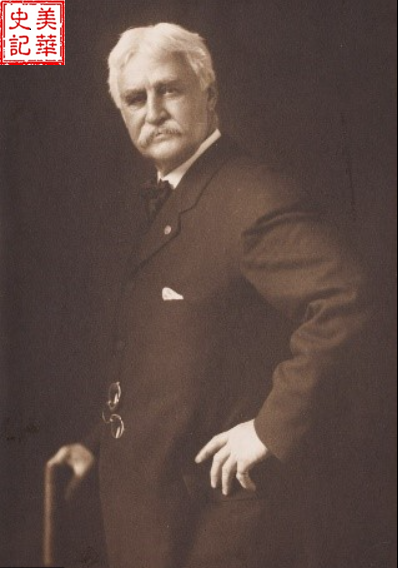

Lee gradually became intrigued by Christianity. In 1876, the famed evangelical minister Dwight L. Moody held a series of revival activities to spread the gospel and arouse religious awakening in Springfield. This had a profound impact on Lee. “I had a personal interview with Mr. Moody, and was strengthened in my resolution to be a Christian,” he wrote. He kept that quiet, though, for fear of being sent back to China.【3】

Picture 3: Evangelical minister Dwight L. Moody. A famous quote of his is, “Faith makes all things possible… Love makes all things easy.”

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwight_L._Moody

Five years later, Yan Phou Lee graduated from Springfield Public School with honors and moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he lived with a new host family and attended Hopkins School, a private high school. During his time at Hopkins School, Yan Phou Lee was an editor of the class paper. In 1880, he graduated as the valedictorian of the class, coming first in English composition and third in Greek. In the fall of the same year, he started college at Yale University.

Just one year later, in the summer of 1881, the Qing government terminated the “Chinese Educational Mission” program due to fears that the young Chinese students were becoming too Westernized. Yan Phou Lee was forced to leave Yale. At the Hartford train station, he tearfully said goodbye to his host family and friends before journeying back west with his fellow students and returning to China by boat.

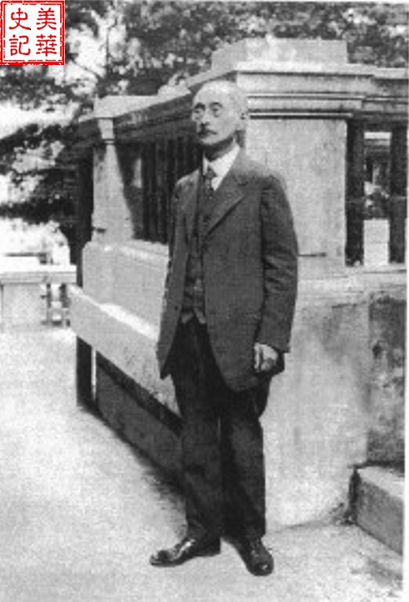

The establishment of the “Chinese Educational Mission” program arose from the China’s Self-Strengthening Movement (1861–1895) initiated by Qing government officials to “facilitate learning from barbarians to control barbarians” and “facilitate the spread of Western learning to the East.” The program began in 1872, and for four consecutive years, 30 boys with an average age of only 12 years old were sent to the United States each year to study abroad. When the program ended in 1881, the 120 children had been living in the United States for at least six years. The founder of the “Chinese Educational Mission” program, Yung Wing, wrote in his autobiography, My Life in China and America, published in September 1909, “In New England, the heavy weight of repression and suppression was lifted from the minds of these young students; they exulted in their freedom and leaped for joy.” 【4】

Picture 4: A statue of Yung Wing in the Sterling Library at Yale University. Yung Wing, the founder of the “Chinese Educational Mission” program, graduated from Yale University in 1854. He was the first Chinese student to study in the United States in the modern era and the first Chinese student at Yale University.

Source: https://images.app.goo.gl/vF3eF487A6oZ5ZJv8

After returning home, the students received an unexpectedly cold reception. Their western education, Americanized attitudes, and rusty Chinese language skills were all extremely dissatisfying to the Qing government – in fact, some students had even adopted Christian beliefs and cut their traditional braids. Russian aristocrats in the 18th and 19th centuries once took pride in imitating Europe, believing that to be close to Europe was to be close to civilization. In contrast, the Qing Dynasty held that China was the center of the world and every other civilization was barbaric in comparison. The Qing government therefore deemed that these returnees were not of much use to their society and could engage only in technical work. Yan Phou Lee was sent to work in the Tianjin Naval Academy. Later, in an interview, he said, “We were treated on our return more like criminals than innocent sufferers. We were confined and watched lest we should run away.” Six months later, he did just that, escaping to Hong Kong while on furlough to work in an English-speaking law firm.

Over the next year or so, he worked to raise funds for his return to the United States, during which he officially became a Christian through a Presbyterian church in Guangzhou. On Christmas Day in 1883, he cut off his braids, donned Western attire, and boarded a steamboat bound for New York. He arrived in February the following year.

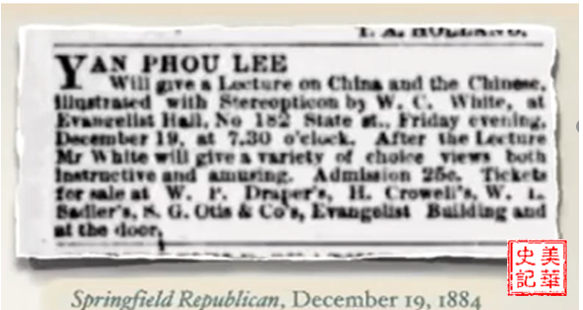

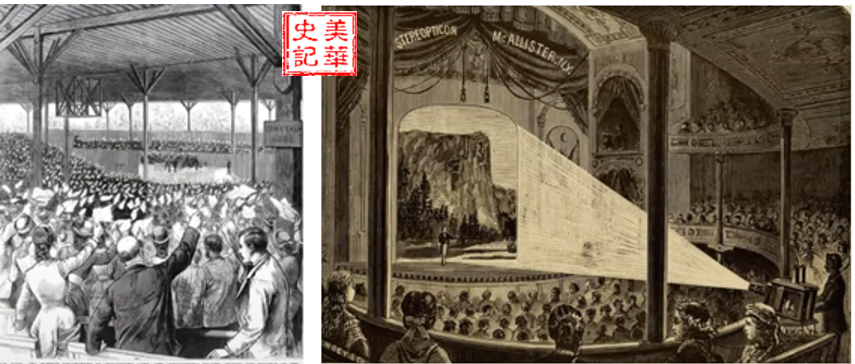

Foreign Encounters with Love and Pain

After returning to the United States, Lee, who had no financial support from his family or the Qing government, took on various jobs with the goal of returning to Yale University and continuing his studies. He felt that Americans had many misconceptions about China’s customs, etiquette, ancient imperial system, and so on, as their only exposure to Chinese culture came from occasional superficial travel notes in the newspapers. So, with his speaking and writing skills, Lee embarked on a career as an orator, introducing China to American audiences. Talks back then, much like TED Talks today, were a convenient and effective way to disseminate information and educate people.” 【5】

With this approach, Yan Phou Lee endeavored to break American stereotypes of China and the Chinese people. He sometimes wore Chinese clothes and a wig with long braids when giving speeches in order to convey the idea that as a bicultural person, he could be ethnically Chinese and wear Chinese clothes and still be an American despite some differences in appearance.

Picture 5: An ad for Yan Phou Lee’s speech

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gdft68sVae8

Picture 6: The scenes of Talks during Lee’s time, but not images of Lee’s speech

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gdft68sVae8

In addition to his career as an orator, Lee also signed on to write for a youth magazine called Wide Awake. From December 1884 to November 1885, the magazine published 12 of his articles with the following titles, in chronological order: Infancy, The house and household, Chinese cookery, Games and pastimes, Girls of my acquaintance, Schools and school life, Religions, Chinese holidays, Stories and story-tellers, How I went to Shanghai, How I prepared for America, and First experiences in America. In 1887, these articles were assembled and published in a book titled When I Was a Boy in China. Yan Phou Lee was considered a pioneering Asian American writer; as his work covered all aspects of his life in China before he came to the United States, it was not only authentic and educational, but also a meaningful conduit of cultural exchange, as his readers came from a range of different ways of life.

Picture 7: Cover of When I Was a Boy in China

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Yan Phou Lee wrote in the Buffalo Weekly Express on August 28, 1884, “I haven’t fully outlined my future. I want, however, to finish my education. Frederick Douglass [the African-American abolitionist and leader] has done great good to his people, and it is my ambition to do all I can for China.”

That fall, relying on income from speaking and writing, Yan Phou Lee returned to Yale University for his sophomore year. During his last three years at Yale, he continued to read and write. He was viewed as “a Chinese scholar, who combines a familiarity with the wisdom of his native land and acquaintance with the civilization and intelligence of America.” His writing covered a wide range of topics and genres. His contributions to the Yale Literary Magazine included not only articles on Chinese history, such as “‘Chinese’ Gordon and the Taiping Rebellion”, but also pieces on the Chinese tea ceremony, “The Romance of Tea”, and the poem, “The ‘Light of Asia’”. He also wrote on ancient eastern philosophy – most notably, Confucius andhis Spring and Autumn Annals. As Yan Phou Lee wrote,

“It is difficult for a European, with his moral training, to appreciate the Ch’un Ts’ew [the transliterated title of Spring and Autumn Annals] or to understand the admiration that has existed for it among the Chinese for twenty-five centuries. Its apparent inaccuracies or willful perversions of the truth are a part of the author’s plan to shield the vices and wickednesses of sovereigns of his state, of whom, according to his creed, no evil should be uttered. To a Chinese, the specimen in the text seems rather a travesty than a translation, for the delicate shades of meaning and the position of the words in the original, which give a clew to the moral nature of the act are lost in the English rendering. The author only echoes the sentiments of Dr. Legge (James Legge, 1815-1897) in his misjudgment of the philosopher. The commentaries on the Ch’un Ts’ew, written some time after it, explain and unfold the principles by which Confucius was guided in writing it, and no Chinese is deceived by it.” 【6】

When Lee graduated from Yale University in 1887, he entered the Pundits and Phi Beta Kappa societies with honors, won awards for speech and writing, and spoke at the commencement ceremony as a graduate representative.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, signed into effect in 1882, was the first immigration bill passed in the United States to exclude a specific ethnic group. It not only barred the Chinese from immigrating, but also prevented those who were already in the country from naturalization, relegating them to the status of perpetual foreigner. At the time of Lee’s graduation in 1887, five years after the Chinese Exclusion Act took effect, the “China question” was still a contentious issue in American politics. Despite this, Lee remained committed to introducing Chinese history, culture and customs to American audiences in a friendly, congenial manner. His commencement speech was unconventional: he denounced racism and prejudice against the Chinese in America and mounted a full defense of Chinese immigrants. In his words,

“The torrents of the hatred and abuse which have periodically swept over the Chinese industrial class in America had their sources in the early California days. They grew gradually in strength, and, uniting in one mighty stream, at last broke the barriers with which justice, humanity and the Constitution of the Republic had until then restrained their fury. The catastrophe was too terrible, and has made too deep an impression to be easily forgotten. Even if Americans are disposed to forget, the Chinese will not fail to keep the sad record of faith unkept, of persecution permitted by an enlightened people, of rights violated without redress in a land where all are equal before the law. Sad it is that in a Christian community only a feeble voice here and there has been raised against the public wrong…”

The Hartford Courant reported: “The oration of Yan Phou Lee of Fragrant Hills, the Chinaman, one of the set pieces of the Center church commencement exercises, was a phenomenal affair. It was frequently interrupted by loud and long applause, which seldom happens at that formal season. He gave his mind a very free delivery, and his was the Chinese side of the story. The way in which he ‘let into’ the government policy made the representatives of the government, to say the least, very attentive listeners.” New York politician Chauncey M. Depew, a graduate of Yale in 1856 who later became a Senator, joked in his witty speech at the alumni dinner: “This morning I heard a dozen—including Yan Phou Lee—speak at Center Church, and I have come to the conclusion the Chinese must go. We can’t stand this kind of competition.”

In response to calls that “The Chinese Must Go”, Lee published his famous article, “The Chinese Must Stay”, in the April 1889 issue of The North American Review. He wrote,

“No nation can afford to let go its high ideals. The founders of the American Republic asserted the principle that all men are created equal, and made this fair land a refuge for the whole world. Its manifest destiny, therefore, is to be the teacher and leader of nations in liberty… How far this Republic has departed from its high ideal and reversed its traditionary policy may be seen in the laws passed against the Chinese…”

A week after his graduation ceremony, at age 26, Yan Pho Lee tied the knot with a wealthy young woman from New Haven, Connecticut. This was the pinnacle of his life: he had just graduated from Yale University, was set to study journalism at graduate school in the fall, recently published a new book, and was surrounded by loved ones.

Picture 8: Yan Phou Lee’s first wife, Elizabeth Maude Jerome (1862-1939). The couple married in 1887 and divorced in 1890.

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

How Yan Phou Lee met and fell in love with 24-year-old Elizabeth Maude Jerome is not well documented, but Lee had lived in New Haven from high school through college, and the two may have encountered each other in church or other social circles. Elizabeth’s family, whose history dates back to the city’s founding, owned land and other assets in the area. Elizabeth was her parents’ only surviving child. Gossip newspapers at the time estimated her expected inheritance to be worth between $65,000 and $100,000 — about $2 million to $3 million today.

The wedding took place at the bride’s home. The well-known pastor Joseph Twichell, a Yale trustee at the time, presided over the ceremony, and guests included Yale professors and Yung Wing. Newspapers across the country reported on the marriage with praise, curiosity, and some teasing, implicitly ridiculing the Chinese. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon at an exclusive summer retreat on Watch Hill, Rhode Island, but a newspaper reported that they cut the trip short because “whenever they take their daily walks abroad, they are gazed at by hundreds of curious eyes.”

Picture 9: Joseph Hopkins Twichell, a famous pastor and author who graduated from Yale University in 1859 and was a close friend of Mark Twain. He was the prototype of the character Harris in Mark Twain’s In A Tramp Abroad.

By the end of 1889, they had two children – a girl, Jennie, and a boy, Gilbert. The previous year, Yan Phou Lee had paused his graduate studies to take a position at a Yale classmate’s family bank in San Francisco. Elizabeth briefly moved to San Francisco with her husband, but soon returned to New Haven.

In 1890, Lee returned to New Haven due to illness, and in May of that same year, Elizabeth filed for divorce, accusing Yan Phou Lee of adultery. In his letter to Pastor Joseph Twichell, Yan Phou Lee expressed that he didn’t want to “have my dirty family linen washed in court.” Lee thus declined to contest the lawsuit. He told the New York Evening World that his mother-in-law had been the source of much of the trouble, and that she hated him “like poison.” The short-lived marriage concluded and disintegrated under unrelenting media attention. After the divorce, Yan Phou Lee was completely cut off from his home in New Haven. Elizabeth reverted to her maiden name, and her two children subsequently took their mother’s surname. Elizabeth and her family did their best to erase any traces of Lee from the lives of the two children, but as their appearances could not be changed, they were treated differently by their peers. “We played alone a lot,” Jennie said later in an interview, “but we were more concerned with cultural things than the others anyhow.”

Picture 10: Sister Jennie Gilbert Jerome (1888-1979)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Picture 11: Brother Gilbert Nelson Jerome (1889-1918)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Gilbert, Lee’s son, graduated with a degree in Electrical Engineering from Yale University in 1910, volunteered to join the U.S. Air Force as a lieutenant during World War I, and was killed in an air battle over France at a young age. His mother and sister went to France to bring his coffin back to New Haven for burial.

After graduating from Mount Holyoke College – at the time, Yale did not admit women – his sister, Jennie, worked as an art librarian at the New Haven Public Library for 35 years. Aside from the four years she was in college, she lived with her mother at their home in New Haven. After Elizabeth died in 1939, Jennie remained in the home alone until her death in 1979, at the age of 91. Elizabeth never remarried, and Jennie never married.

Wandering Without a Trace

The divorce must have cost Yan Phou Lee some of the friendships and social capital he had built in New Haven and New England over the previous 17 years. He felt he had no choice but to leave a place where he was apt to feel troubled and wandered the country for the following decade, working a variety of jobs. However, distrust, discrimination, and exclusion haunted him throughout.

Lee hosted a Sunday school journal in New York, served as an interpreter in a New York courthouse, ran a vegetable farm in Delaware, owned a country store, was a fortune teller at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (if a newspaper report is to be believed), wrote an exposé for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about gangsters running Fan-Tan games, worked as an assistant of a Chinese school in Wilmington, North Carolina, lectured in the South, briefly attended medical school at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, and organized the China exhibitions at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in 1897 and the National Exports Exposition in Philadelphia in 1899.

Picture 12: Fan-Tan Game Hall in Guangdong, China in 1890. Fan-Tan is a gambling game that was once popular in Guangdong, Guangxi in southern China and Chinatowns in the United States.

Source: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%95%AA%E6%94%A4

Yan Phou Lee met his second wife, Sophie Florence Bolles, in Tennessee. They married in 1897 and had two sons, Clarence Vaille Lee and Louis Emerson Lee. In 1904, the family settled in northern New Jersey.

Picture 13: Yan Phou Lee’s second wife, Sophie Florence Bolles (1876-1960). The couple married in 1897 and divorced in 1933.

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

For many years, Yan Phou Lee worked as an editor for two small-town newspapers in New Jersey and ran a poultry business in Chinatown. In the 1920s, he served as managing editor of American Banker Magazine. Of this job, Lee wrote in his 50th Yale reunion book that he “did my best to make it a good financial journal.” When he resigned before returning to China in 1927, the publisher honored him for his work and awarded him with a watch.

Though Yan Phou Lee’s second marriage lasted more than 30 years, his granddaughter, Penny Lee Winfield, recounted, “It was not a very successful marriage… Sophie Florence was most likely not the nicest woman in the world, and Yan Phou Lee came here so young. He was close to his American host family, but I don’t think he ever developed the interpersonal skills to form close relationships.” His great-grandson, Benjamin Lee, says “I think he was someone who didn’t feel at home anywhere.”

Lee once expressed a cynical attitude about his checkered career. Perhaps it was this very dissatisfaction that eventually led him to leave his family at the age of 65 and return to China alone. In an 1894 interview, he is quoted as saying, “As for my future plans, I have learned not to make any. My motto is ‘Expect nothing, and you won’t be disappointed.’”

Picture 14: Yan Phou Lee in the 1920s.

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

After returning to China, Lee first taught English in Guangdong and later edited the English edition of the Canton Gazette in Guangzhou from 1931 to 1937. In 1938, the Japanese began to bomb Guangdong. On March 29 of that year, he wrote in his final communication with his Yale class, “We are having war here, inhuman, brutal, savage war. Japanese bombing planes raid the city every day—sometimes three or four times. One has to think of saving his life. Little time can he give to such a thing as Class histories.” Lee’s American children received his last letter in 1938. It is presumed that he perished in the bombings, but if his body was recovered and the exact circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

Yan Phou Lee, an outstanding graduate of Yale, lived a life at first filled with hope. But after an embarrassing and frustrating journey, he ultimately disappeared without a trace. We may wonder, if Lee was a stateless citizen – then where is the resting place of his soul? Perhaps it is somewhere between China and America, a distinct place where Chinese-Americans can neither fully fit in nor fully escape.

Appendix: Descendants of Yan Phou Lee and his Second Wife

The two sons of Yan Phou Lee and his second wife, Sophie, grew up in New Jersey. Their eldest son, Clarence Vaille Lee, was a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. He served in the Pacific and Panama Canal Zones in the 1920s and 1930s, and later in World War II. After the war, he returned to Annapolis, Maryland, where he taught celestial navigation until his retirement. He died in 1983.

Their younger son, Louis Emerson Lee, graduated from Yale University in 1927 with a degree in Engineering and worked in construction on Long Island, New York. After serving in the military during World War II, he and his family settled in New Canaan, Connecticut, where he later started his own construction company. He died in 1989.

Picture 15: Yan Phou Lee’s eldest son, Clarence Vaille Lee (1898-1983)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Picture 16: Yan Phou Lee’s youngest son, Louis Emerson Lee (1903-1989)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Clarence and Louis’s lives were not devoid of racism. In Clarence’s college yearbook, his nickname was a racial slur. While serving in the Navy in San Diego, California in 1938, Clarence had to go to Arizona to register his marriage with his white fiancée, Virginia, because intermarriage was illegal in California at the time. Louis and his wife tried to join the New Canaan Country Club, but they were rejected because of Louis’s Asian identity.

Clarence and his wife had a son, Russell Vaille Lee, who died in 2020.

Louis and his wife had a son and a daughter who grew up ignorant of their Chinese ancestry. Their son, Richard Vaille Lee, obtained his undergraduate degree from Yale University in 1960 and his medical school degree in 1964. He was a professor of School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at State University of New York at Buffalo. In the 1980s, he traveled to China on a medical delegation, accompanied by his wife Susan and their sons Matthew Vaille Lee and Benjamin Lee. The trip sparked Richard’s interest in his grandfather and the “Chinese Educational Mission” program. With his efforts, Yan Phou Lee’s book, When I Was a Boy in China, was republished in 2003. Richard also established an exchange program that sent his medical students to Beijing for short-term internships. He died in 2013.

Louis’s daughter, Penny Lee Winfield, had three children and two grandchildren.

Picture 17: Yan Phou Lee’s grandson, Richard Vaille Lee (1937-2013)

Source: http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2013/05/017.html

Picture 18: Yan Phou Lee’s granddaughter, Penny Lee Winfield (1944-)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Richard’s eldest son, Matthew Vaille Lee, graduated from Georgetown University with a degree in International Relations in 1989. He joined the Agence France-Presse (AFP) where he covered the State Department, and served successively as the Kenya-based deputy bureau chief for East Africa and Indian Ocean in Kenya, and bureau chief in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. He currently works as the State Department correspondent and diplomatic writer at Associated Press. He has traveled with every Secretary of State since Madeleine Albright, reporting from more than 120 countries on America’s evolving international interests and priorities.

Picture 19: Yan Phou Lee’s great-grandson, Matthew Vaille Lee (1965-)

Picture 20: Yan Phou Lee’s great-grandson, Benjamin Lee (1968-)

Source: https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

Richard’s youngest son, Benjamin Lee, graduated from Yale University with a bachelor’s degree in 1992 and a master’s degree in East Asian studies in 1999, becoming the fourth generation to graduate from Yale in the family. He began learning Chinese after visiting China with his father in the 1980s. After graduating with an undergraduate degree, he went to China to teach English through Yale’s China Program, then returned to Yale to pursue a master’s degree. He taught in private schools in the United States for many years and was hired as the high school principal of the Pudong campus of Shanghai American School six years ago.

Notes:

【1】https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee

【2】ibid

【3】ibid

【4】https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gdft68sVae8

【5】ibid

【6】ibid,https://youtu.be/Gdft68sVae8?t=2584

Main Reference:

- https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/5324-yan-phou-lee Author:Mark Alden Branch

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gdft68sVae8 Speaker: J. Michael Duvall

Title in English:

Where Could I Mourn —— The Life Story of Yan Phou Lee from the “Chinese Educational Mission” program

English Summary:

Yan Phou Lee came to the United States at the age of 12 via the “Chinese Educational Mission” program. He graduated from Yale University in 1887 and was the first Asian American author to publish a book in English.

Over his more than 50 years spent in the United States, Lee participated in a groundbreaking program that educated Chinese boys in American schools, lectured widely about Chinese culture, wrote and edited for newspapers and magazines, lobbied against the “Chinese Exclusion Act”, and fathered four children.

His story is a tale of Western idealism, virulent racism, bravery, heartbreak, and tragedy.