Author: Xin Su

Translator: Audrey M. Jiang

“Nothing and no one can destroy the Chinese people. They are relentless survivors. They are the oldest civilized people on earth. Their civilization passes through phases but its basic characteristics remain the same. They yield, they bend to the wind, but they never break.”

–Pearl S. Buck

It was some of the bloodiest ten years of their history, but it was also a time of change, and a time of hope…

The upheaval caused by the Second Sino-Japanese War brought on an unprecedented degree of unity among Chinese in America. They threw themselves with a new fervor into spreading the word of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and some descended into battle to further their cause there. In December 1941, after the U.S. declared war on Japan, the U.S. and China allied themselves in the fight against fascism. The long-suffering Chinese Americans had weathered through the vehemently anti-immigrant political climate of the Chinese Exclusion Act and had finally become welcomed, respected members of society.

If only we are willing to see it, there exists a great commonality between different groups of people. Pearl S. Buck and her husband, both of whom harbored a deep appreciation and compassion for the Chinese people, fought with the Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion to end the Chinese Exclusion Act. Their untiring efforts were critical in dismantling the 61-year-long policy of excluding Chinese immigrants.

1931: Japan Invades China

China: Within 100 days of the Mukden Incident, which occurred on September 18, 1931, the Japanese army occupied all of Manchuria. On March 9, 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Chiang Kai-Shek, the then-leader of the Republic of China, emphasized the dangers of going to war with Japan, instead opting to cede the three provinces of Manchuria to Japan.

The Japanese invasion set Chinese Americans on edge, particularly those who had family in China. As a result of the Japanese invasion, Chinese Americans faced both the abandonment of China by international society and racism from within the United States.

Where then, did salvation lay for China?

What then, was to be the fate of Chinese Americans?

Nobody knew. Nobody came to their aid, so Chinese Americans had to take the reins. They had to save themselves.

Chinese Americans immediately denounced Japan’s invasion of China. Chinese newspaper China West Daily (also known as Chung Sai Yat Po) advocated for China declaring war on Japan [1]. Chinese newspapers also enthusiastically sang the praises of those “national heroes” bravely fighting the Japanese invaders. Northeastern Army general Ma Zhanshan publicly defied Chiang Kai-Shek’s orders not to resist the Japanese army, engaging them in a fearsome battle. Chinese American newspaper Chinese Journal was the only one to report on this matter. As a result, the newspaper’s sales skyrocketed almost overnight, selling 10,500 copies [2].

The oldest Chinese political organization in the United States, Chee Kung Tong, and the New York Chinatown-based organization, On Leong Chinese Merchants Association, published an open letter in which they condemned the Chinese government’s non-resistance policy [2]. The initially Kuomintang-supporting Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) eventually joined other traditional Chinese organizations in opposing Chiang Kai-Shek’s no-resistance policy. They contacted both the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and the Chinese Communist Party, calling on them to work together to fight the Japanese [1]. The CCBA also sent a telegram to the President of the United States, asking him to intervene in Japan’s aggression [3].

On September 24, the CCBA convened all of Chinatown’s Chinese political organizations, forming the Association of Chinese in America Backing Resistance to Japan and National Salvation. The organization promptly organized boycotts of Japanese goods, protests against Japanese invasion, and fundraisers in support of China [3]. In just three months, Chinese Americans raised $625,000, all of which was donated to Ma Zhanshan [3].

The Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance was a left-wing working-class Chinese American organization, of which many members did sympathize with the Chinese Communist Party. They emerged as a leader of the new Japanese resistance movement. After 1934, they became one of the faces of the more progressive side of Chinese American politics.

When the whole world became aware of Manchuria’s non-resistance, Chinese generals who had adopted a strict “no surrender” policy won the love and respect of many Chinese living overseas, including Chinese Americans. In 1932, 19th Route Army commander Cai Tingkai refused to comply with Chiang Kai-Shek’s order to withdraw troops out of Shanghai. He and his army bravely fought the Japanese for many months, thwarting the Japanese army’s plans for a quick occupation of Shanghai. Chinese Americans once again donated a sum of $750,000, of which a large portion went toward Cai Tingkai and relief for Shanghai refugees [2,3]. In 1934, when Cai Tingkai traveled to California to drum up support for his cause, he was welcomed as a hero by the Chinese American community. Patriotic members of the community gathered around Cai Tingkai, cheering whenever he gave a speech. Six Chinese restaurants teamed up to prepare a lavish welcoming banquet. Fireworks were set off, and the lights of the shops of Chinatown glowed golden deep into the night [3].

Meanwhile, Japanese resistance organizations popped up in Chinatowns all across the United States, such as the “Anti-Japanese Association,” “National Salvation Association,” or the “National Salvation Fund Savings Society.” During the 1940s, as the Japanese encroached deeper into Chinese heartland, Chinese Americans continued to raise funds in support of China and urge both the American government and people to support China [1]. This time marked a change in many Chinese Americans’ perspective on their power and rights in government.

The Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance publicly criticized the “luxurious lifestyle” of Chinese Americans, and organized discussions on Chinese current affairs, as well as establishing social clubs (such as Quan Shar) and youth groups [2].

Some Chinese Americans had already established private aviation schools and clubs to train young pilots as early as 1920. Japan’s invasion ushered in an era of rapid development for Chinese aviation. The Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance vigorously implemented and supported the training of young Chinese pilots.

Katherine Cheung (shown below) was the first Chinese woman to be granted a private pilot’s license by the United States[4].

Figure 1:The first Chinese American woman to receive a pilot’s license, Katherine Sui Fun Cheung. The Enping Aviation Museum, Chinese Aviation Museum, and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum all have exhibits on her [5]. In 2016, her life was made into a documentary, Aviatrix: The Katherine Sui Fun Cheung Story.

At that time, Chinese aviation schools did not accept female students. Even in the United States, only 1% of licensed pilots were women. Before Katherine Sui Fun Cheung, only one Chinese American woman, Ouyang Ying, had ever been trained in aviation. Unfortunately, Ouyang Ying died in an aviation accident when she was only 25, before she had an opportunity to achieve her dreams [5].

Katherine Cheung was born on December 12, 1904, in the city of Enping in Guangdong province. While the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect, the immigration of Chinese laborers was restricted, but businessmen, merchants, and traders could still immigrate. Cheung’s father was a businessman who had dealings in America, and so she was allowed to come to Los Angeles to study music at 17.

Cheung’s decision to pursue aviation was completely an accident. When her father took her to Los Angeles’s Dycer Airport to learn how to drive, she became fixated on the idea of learning to pilot a plane.

After getting married and having two daughters, Cheung made up her mind to take flying lessons. She joined the Chinese Aeronautical Association’s aviation class, taking lessons at $5 an hour [4]. She earned her private pilot’s license on March 30, 1932, becoming the first Chinese woman to receive a pilot’s license in America. This news caused a sensation locally, and was widely reported on [4].

Cheung worked hard, and continued to learn and improve. She eventually received a commercial pilot’s license [7] and an international pilot’s license [8]. She became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1936, but still retained dreams of returning to her homeland. She saw huge potential for aviation services in fulfilling the transportation needs of areas with underdeveloped infrastructure, and hoped to return to China someday to teach aviation to these areas [9].

After the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Cheung decided it was time to return to China to open that flight school she always talked about [9]. She promoted her ideas in the Chinese American community and managed to raise $7000 [8], which she used to buy Ryan ST-A’s (a type of plane). But then tragedy struck: In an unfortunate accident, her cousin died while testing her plane [7]. Shaken, Cheung’s father made her promise to give up flying [8]. Cheung did not do so at first. However, following the successive deaths of many of her relatives, she was persuaded to give up flying in order to care for her elderly mother. She retired from the skies entirely in 1942.

During World War II, Cheung served as a flight instructor. After the war, she managed a flower shop, retiring in 1970. In the 1990s, she moved from Chinatown to Thousand Oaks, California, where she would spend the rest of her life. She died on September 2, 2003, aged 98 and is interred at Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills, in Los Angeles [10].

Figure 2: Director Ed Moy and assistant director Katherine Park had the honor of interviewing Katherine Sui Fun Cheung’s daughter. The three reflected on Cheung’s long life. In her lifetime, Cheung must have faced both racism and misogyny, yet resolutely pursued her dreams anyway. In addition to being a pilot, Cheung was an active member of her community. She is an inspiration to Chinese Americans, especially women. Picture source: https://www.msnbc.com/the-last-word/watch/herstory-amazing-aviatrix-katherine-cheung-605367363855

Video: https://vimeo.com/207580570

1937: The Beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War

China: The Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937 led to the fall of northern China, after which full-scale war erupted between Japan and China. On July 26, 1937, Claire Chennault accepted a job offer by the Kuomintang. Chennault was a retired major in the United States Air Corps (a forerunner to the U.S.’s present-day Air Force). While in China, he led a group of volunteer American pilots in helping to train and develop China’s budding Air Force [10].

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident incited the anger of many Chinese Americans.

On the night of July 7, many Chinese American communities met to form war relief committees [5]. In San Francisco, left-wing groups, the Kuomintang, and other political groups met to discuss the situation. In New York, the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance and other left-wing groups went to the Chinese embassy to express a mutual desire to fight Japan [2,5].

The China Daily News reported: In just a few hours, we have mobilized groups from all the Chinese American communities– Chinese Americans from the highest to the lowest social class have united into one, with the goal of resisting Japanese brutality.

Chinese Americans raised money through parades and “Rice Bowl” parties, which proved to be extraordinarily effective [2, 5]. On August 21, 1937, the CCBA gathered 100 representatives from 91 different community organizations. At that meeting, they formed the China War Relief Association (CWRA). CCBA chairman Fang Wenjie was elected as the organization’s leader [3].

Within a week, in San Francisco alone, they had raised $30,000. The biggest individual donation (of $15,000) came from dollar store owner Joe Shoong. It was said that his hundreds of employees pledged one month of their own salaries toward the war effort. Other Chinatown businessmen quickly followed his example [3]. Chinatowns in San Diego, Fresno, Tucson, Phoenix, and New York City all created organizations dedicated to raising money for China [1].

Coercive measures were sometimes used to raise money. For example, every employed person could be required to donate $30, on threat of punishment. Said punishment involved having their names and addresses made public, and in extreme cases violators were paraded through the streets of Chinatown [3].

In November 1937, the CWRA launched a second round of fundraisers. Protests, consisting of about 300 volunteers and students, raised banners and signs on the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Their protest slogans were “Voluntary Giving to Save the Nation” “Military Resistance to the End,” and “Racial Freedom and Liberty Forever.” This last one is notable because it was under this slogan that Chinese Americans combined their Japanese resistance and advocacy of democracy and civil rights into one cause. In this way, the struggle against Japanese invasion became deeply linked to Chinese Americans’ fight against racism in America [1].

On May 9, 1938, with a sponsorship from the CCBA, about 12,000 Chinese Americans from New York City and other East Coast cities marched about three and a half miles through Chinatown in a public demonstration supporting China. It was one of the largest such demonstrations of its kind. The demonstrators came from different walks of life, but came together for this one cause. It was reported in Manhattan that 1,500 Chinese laundry shops, restaurants, and stores closed at five to let everybody have a chance to participate in the demonstration. The protestors were divided into ten divisions of 1000 people each. Above the crowd flew six Chinese fighter planes that had received training at Roosevelt Field. In the demonstration, there were floats, dragon dancing, banners, bands (playing both Chinese and American music), and thousands of flags [1].

Figure 3:Here CCBA leaders are shown holding a “China Defense” sign and a giant portrait of Chiang Kai-Shek. At protests, they would wave placards of “War in China– Made in Japan!” Picture source: http://orientallyyours.tumblr.com/post/79959190693/chinese-humiliation-parade-may-10-1938-new-york

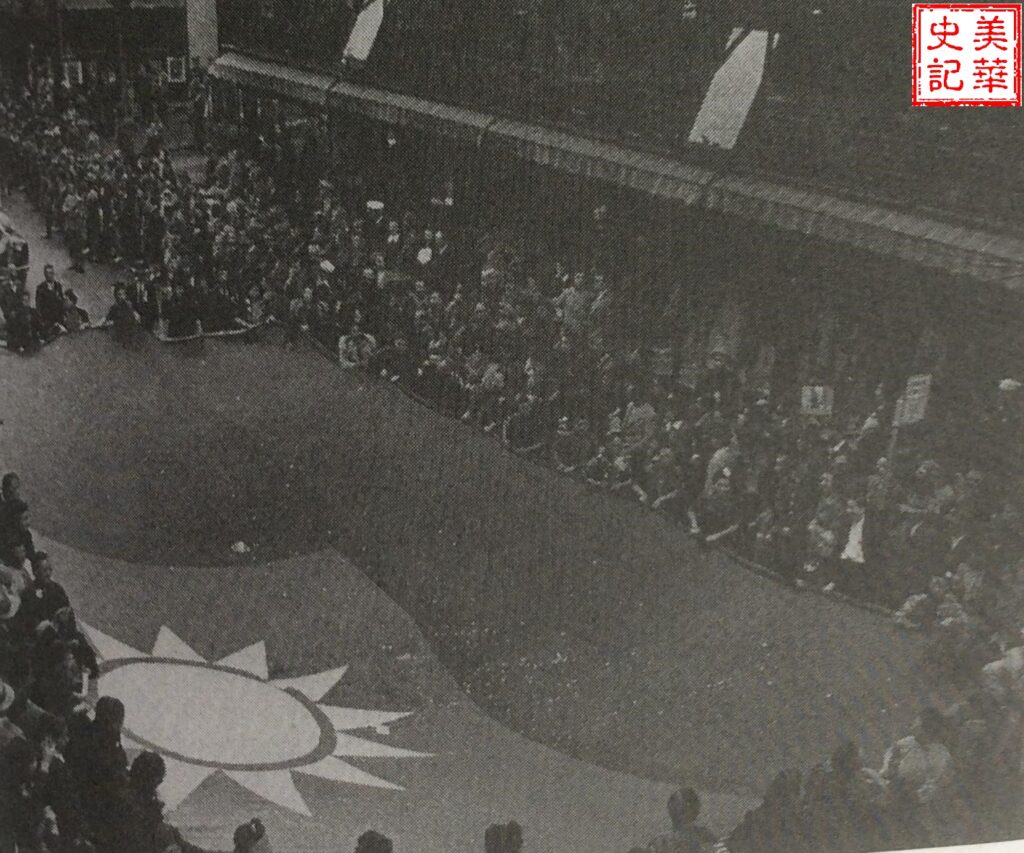

Figure 4:Hundreds of women lift a Chinese flag measuring 75 feet long, 55 feet wide, and weighing 300 pounds. People threw money on the flag in demonstrations. Because so much money was thrown, they had to stop at least 3 times to empty the money before continuing in the procession. Picture source: [3].

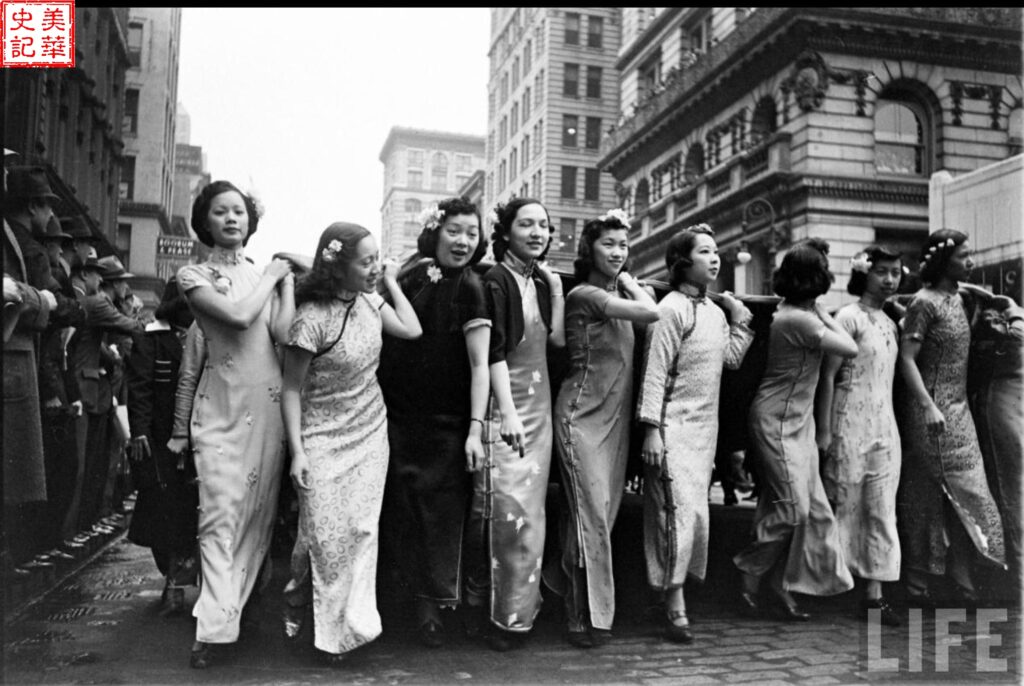

Figure 5:Chinese girls wear qipao to attend the May 9 demonstration. The New York Times reported: “Though no appeal was made for funds, the spectators began showering coins—pennies to half dollars, and even dollar bills—onto the flag. About $300 was collected.” Picture source: http://orientallyyours.tumblr.com/post/79959190693/chinese-humiliation-parade-may-10-1938-new-york

Figure 6:Parades and rice bowl parties proved to be among the most effective methods for raising money. According to Chinese Digest, the first rice bowl parties were held all across the country on June 17, 1938. Over 200,000 people attended the first rice bowl party in San Francisco. These rice bowl parties consisted of a parade, followed by cultural entertainment. This generally entailed fashion shows, dances, Chinese and Western music, theater performances, mock air raids, and dragon dances. Locals would also dress up in traditional Chinese dress, imitating beggars. Children rode floats, raising alms bowls and asking for donations to fill the “Chinese rice bowl.” Because of this, these events came to be called “rice bowl parties.” The first rice bowl parties in San Francisco raised a total of $55,000. A second round of rice bowl parties were held from February 9 to 11 in 1940, which raised $87,000 over the course of three days.

A four-day event, in May 1941, raised $93,000 [3]. Picture source: https://www.sfchronicle.com/thetake/article/Chinatown-charity-79-years-ago-SF-s-Rice-Bowl-10883976.php

In the eight years after Japan invaded China, Chinese Americans donated $20 million toward the Chinese war effort. San Francisco’s Chinese American community was the biggest contributor, donating a total of 5 million dollars [3].

Chinese Americans from all levels and parts of society participated in the Japanese resistance movement. There were new immigrants, American-born second generation Chinese Americans, teenagers, and young adults alike who associated themselves with the movement. Many of them went from door to door, selling war bonds. Chinese American volunteers served under the Red Cross, transporting medical supplies, vaccines, and other such goods to China. Chinese American doctors organized blood banks and offered medical assistance [6].

At that time, Americans living outside Chinese American communities gradually became more aware of Japan’s atrocities in China. They were initially shocked, but that shock was later transformed into support for China.

From 1937 to 1938, the American-dominated Washington Commonwealth Federation (WCF) launched a movement resisting Japanese aggression, based in Seattle and the West Coast. Formed in 1935, the WCF was a left-wing coalition of communists and other activists under the Democratic Party. By boycotting Japanese goods, they hoped to weaken Japan’s advance into China [12].

On July 24, 1937, the WCF published an issue of its weekly newspaper The Sunday News, calling on the United States to ban the sale of goods to Japan [13]. Two weeks later, they published another article urging the boycott of Japanese-made products, as well as demanding that Japan “respect the territorial integrity and sovereignty of China [14, 15].” From November 6, 1937 onwards, The Sunday News regularly published the words “boycott Japanese goods” in their newspapers, [16] and reported on the state of the war between Japan and China.

In the following few weeks, The Sunday News drew attention to the United States’s shipment of strategic supplies to Japan [17]. One chart indicated that the United States had sent $200,000 worth of war materials to Japan in the month of July alone. Most of these goods had been shipped out from Seattle, one of the main ports of the West Coast. The WCF expanded on their position on August 21, in an issue debating the Nine-Power Treaty and the Neutrality Act. The WCF did not seek neutrality in the China-Japan conflict, but rather allyship with China. In the two months afterward, The Sunday News continued to discuss the importance of respecting the Nine-Power Treaty, and demanded an immediate halt of the shipment of war goods to Japan [12].

The boycott, though planned, lacked in economic strategy: in the two years that it was in action, it harmed the finances of small business owners, caused local businesses to suffer losses, and did not even manage to shake the Japanese economy. However, it did raise the awareness of the general American public, who gained a better understanding of Japanese militarism [12].

Chinese Americans also participated in the boycott. They disapproved of American shipments of war goods to Japan, war goods that would ultimately be made into weapons to take the lives of Chinese people. Their methods included preventing American ships (containing scrap metal and other war materials bound for Japan) from leaving harbor.

In January 1938, 39 San Francisco sailors refused to transport a ship’s worth of scrap iron and were fired for it. Within a few months, Chinese Americans from coast to coast followed their example. Together, they managed to successfully halt the shipment of raw war materials to Japan [6].

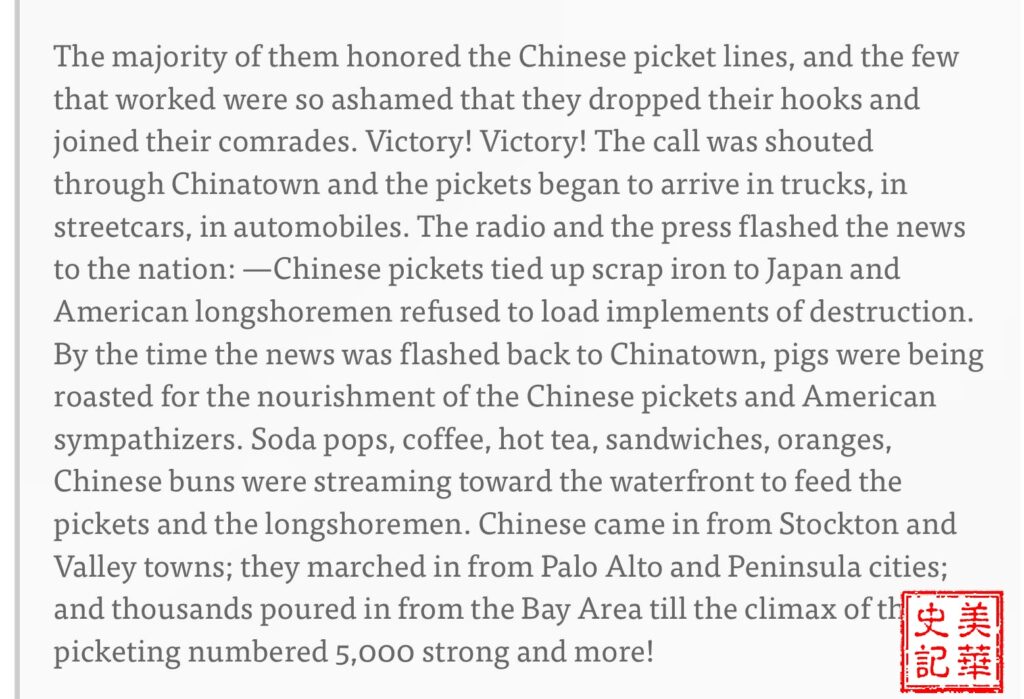

In December 1938, the SS Spyros, a Greek freighter chartered by the Japanese Mitsui Company, docked at San Francisco with 8500 tons of scrap iron bound for Japan. On December 16, under the leadership of the United Chinese Societies, around 200 Chinese volunteers and 300 volunteers from other ethnic groups headed to Pier 45 to stop the SS Spyros. They gave speeches and formed pickets to block the pier. When the longshoremen went to lunch, the crowds shouted at them: “Longshoremen, be with us!” After lunch break, only a small number of longshoremen returned to work– most of them entered the picket lines [6].

Figure 7: An article from Chinese Digest reporter Lim P. Lee. The Chinese picket lines received support from the general public. People in Chinatown supplied the picketers with food. As new people joined the picket lines, the number of people picketing reached 5,000 strong. Picture source: https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2007/julyaugust/feature/parades-pickets-and-protests

The protests continued for four more days, until December 19, at which point there were about 5000 people picketing. The Waterfront Employers’ Association then issued an ultimatum to the protestors: break up picket lines and return longshoremen to work. If the picketers refused, they would not only continue to trade with Japan, they would tie the shipping business of San Francisco and the entire West Coast to Japan. The tense situation was saved by the intervention of the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), which opened negotiations for an amicable solution that would not “let the Chinese down.” Finally, they came to an agreement: they would gather all labor, civic, and religious groups together to study and push for an embargo on all goods to Japan [6,1].

Chinese Americans successfully attracted the attention of people to the issue of the sale of war materials to Japan, and also won the support and cooperation of other Americans in doing so.

On December 20, the United Chinese Societies announced their victory and withdrew all picket lines. They held a mile-long parade in celebration, singing “March of the Volunteers” (China’s resistance song). The parade marched past the wharf headquarters and downtown San Francisco, finally returning to Chinatown [1].

The CWRA, labor and other organizations quickly helped lobby for the end of arms sales to Japan.

From late 1938 to early 1939, Chinese Americans and other Americans gathered in displays at docks in San Francisco, Long Beach, Portland, and Seattle. They sought to educate people that most Japanese war material came from the United States. Speakers of the movement also urged American consumers to not buy Japanese goods in order to cut off Japan’s war funding.

Figure 8:WCF was very successful in its boycott of Japanese goods. They narrowed their scope from a boycott of Japanese goods in general to a boycott of daily necessities only. The WCF Sunday News called on women to boycott silk. Picture source: http://depts.washington.edu/depress/washington_commonwealth_federation_japanese_boycott.shtml

Boycotts of Japanese goods permeated deep into the minds of the people, so that they refused to buy even the simplest of Japanese products. They were steadfast in their belief that they were helping to create peace and combat war crimes [12].

In 1940, the number of Chinese children born in the United States exceeded the number of first-generation immigrants for the first time. Many American-born Chinese did not have a good understanding of China. Because of this difference in experience and perspective, these two parts of the community sometimes found themselves disagreeing with each other. The war, though terrible and tragic, did help unite the Chinese American community [6]. At the same time, the boycott movement also lessened the Chinese American community’s isolation, and intertwined them and other ethnic groups also opposing Japanese invasion. Chinese Americans informed the public of Japanese atrocities in China through rallies. In New York, the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance distributed thousands of English flyers in their laundry shops, urging Americans to boycott Japanese goods [6].

The new unity of Chinese Americans in the eyes of the public caused them to shed their image of tong wars and infighting, bringing forth a new era of integration with mainstream American society.

1941: The Occupation of Taishan, Attack on Pearl Harbor, and China-United States Alliance

China: On March 3, 1941, about 1000 Japanese soldiers on naval ships landed at Guanghai and Sanjia, where they occupied the city of Taishan in Guangdong [18]. From there they moved on to occupy Hong Kong, cutting off one of the most important routes between the United States and China. Chinese Americans could no longer send money to their relatives in Taishan. Many of these Taishan families then lost their main source of income, and were forced to sell their jewelry, furniture, and other possessions to survive. Many wives were forced to become prostitutes or sell their children [6]. In the short four years between 1941 and 1945, Taishan was occupied a total of 5 times. Of the about 150,000 people living in Taishan, about a quarter were killed or went missing during the war.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise military strike on Pearl Harbor. Afterwards, the United States officially declared war. The American volunteers who were training the fledgling Chinese air force became incorporated into the American Air Force. Claire Lee Chennault was appointed as the commander of the Air Force in China, commanding the First American Volunteer Group in China to fight against Japan. This group eventually became known as the famous “Flying Tigers” [11].

The attack on Pearl Harbor further angered Chinese Americans.

Chinese Americans gained a sense of heroism, as well as a sense of purpose. They felt a duty to protect the country that they lived in– the United States– but also to save China, all the way on the other end of the world. Yes, Chinese Americans were finally stepping up…

During World War II, it is estimated that around 15,000-20,000 Chinese Americans joined the army, around 20% of the mainlander Chinese American population. The rate among Americans in general was only 8.6%. The proportion among New York City Chinese Americans, however, was even greater, at an astonishing 40% of the Chinese American population [2,6].

Some Chinese Americans may have enlisted in order to receive American citizenship, but there were also American-born Chinese Americans for whom the only reason to enlist was patriotism.

Chinese American David Gan said: “I had never felt so happy and proud that I was an American, ready to fight for my country even if it meant that I must give up my life [6].”

Regrettably, the era was still deeply entrenched in racism. African Americans and Japanese Americans were strictly segregated from white soldiers in the military. Chinese Americans, however, represented more of a gray area and were allowed to mingle with white soldiers in some parts of the army [6]. To many of the young white men in the military, World War II was the first time that they had ever shared space with people of other races. At times, they forced Chinese Americans to do the heaviest work, or refused to sleep in the same rooms with their Chinese compatriots. Even being in the army, where differences between men are obfuscated through uniform, and the price of disunity is deadly, was not enough to erase the racism so heavily prevalent in American society [6].

Even so, being in the army gave many Chinese Americans a chance to participate in society and strengthened their sense of self-identity. They felt that they were not only Chinese, but also American.

The times demanded for heroes– and heroes there were! Especially Chinese American heroes.

On December 7, 1941, the very day that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, University of Hawaii student Stanley Wilfred Lau was called to active duty. He later joined the newly-formed “Army Air Corps Cadet Program.” After his training, he became a fighter pilot.

Figure 9:Stanley Wilfred Lau. Picture source: http://www.americanairmuseum.com/person/241699

He began his flying career in California, but was soon transferred to Europe and Africa as a P-38 fighter pilot. In that time, Stanley flew more than 50 combat missions, destroying multiple enemy aircraft. In addition to his combat operations, Stanley also served as the Director of Fighter Divisions, Director of Air Defense Plans of the Pacific Air Command, and Director of Air Defense Operations for the Far East (which included Japan, South Korea, and Okinawa). He also developed the Japanese Air Defense System and trained ground and air personnel [19].

Stanley retired from the military in 1964 and returned to Honolulu to begin the second stage of his life. In Honolulu, he was an educator, school administrator, and the Federal Grants and Applications Administrator for the State of Hawaii Department of Education. He retired permanently in 1985 [19].

Figure 10:Gordon Pai’ea Chung-Hoon(July 25, 1910 – July 24, 1979, Honolulu, Hawaii) United States Navy admiral, and the first Asian American flag officer. He was the first Asian American student to graduate from the United States Naval Academy, in May 1934. From May 1944 to October 1945 he was a commanding officer in the Marine Corps. He received both a Navy Cross and Silver Star for his bravery. Picture source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gordon_Chung-Hoon

Another hero that we should recognize is second-generation Chinese immigrant Gordon Pai’ea Chung-Hoon. From May 1944 to October 1945, he was commander of the destroyer USS Sigsbee. In the spring of 1945, the USS Sigsbee helped bring down 20 Japanese planes. On April 14, 1945, while at a radar picket station in Okinawa, a kamikaze aircraft crashed into the Sigsbee. The attack damaged the ship’s engine and steering controls. Despite the sorry state of the ship, Chung-Hoon managed to sustain anti-aircraft fire against enemy air attacks while also successfully directing the Sigsbee into port [20].

When this cruel war descended on the world, Chinese women bravely took up important social responsibilities.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hazel Ying Lee became the first female Chinese American pilot to lay down her life for her country. Because of the scarcity of male pilots, the United States started to recruit female soldiers to fly newly manufactured planes from factories to training bases, docks, and other centers of transportation. Ying Lee was one of these women, servicing Romulus Field in Michigan.

Initially, she tried to join the Chinese air force in Guangzhou, but was refused entry despite the need for pilots in China. When the United States declared war on Japan, she jumped at the chance to finally contribute to the anti-Japanese war effort and so returned to the United States [6, 21].

Figure 11: An instructor evaluates Ying Lee’s performance during training. Hazel Ying Lee was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1912. After graduating from high school, she held a job as an elevator operator in a department store, the only job she could find in a time of few opportunities for people like her. She had an adventurous personality and took flying lessons from the Chinese Flying Club of Portland, receiving her pilot’s license in 1933. Picture source: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/first-chinese-american-woman-to-fly-for-military-died-in-fiery-crash/

Sarah Byrn Rickman, who has written extensively about these female pilots, once wrote: “For women to be flying a nearly 400-mile-per-hour aircraft clear across country, not daily, but almost daily, was mind-boggling, when you consider that most women, in fact most men — we’re talking about the 40s — had never been out of their home state, maybe even out of their home county.”

This job was also very dangerous, because planes fresh off the assembly line were prone to quality problems. Of the 1,102 women who participated in this program, 38 of them died. Ying Lee was the last of them to die. While transporting a P-63 en route from New York to Montana, her P-63 crashed into another P-63. Her flight jacket was still burning when they pulled her from the plane. She died two days later, of her burn injuries, on November 25, 1944. She was only 32 years old [6, 21].

Figure 12:Ying Lee was one of the 38 women pilots who sacrificed their lives to their countries during World War II. Sexism in the military was evidently still an enormous problem, as even though these female soldiers performed military duties, they were not treated as military members. This problem was only addressed 30 years later, when Congress voted that they were eligible for veterans’ benefits. PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Racism for Chinese Americans, as well as many other minorities, followed like a shadow in their wakes. Once, during training, Ying Lee’s plane’s engine malfunctioned, and she was forced to make an emergency landing in a farmer’s field. According to records from the U.S. Air Force, the farmer mistook her for a Japanese pilot and tied her up.

Shortly after Ying Lee’s death, her brother Victor, who was serving in the American tank force in France, was also killed. Their parents wished for them to be buried side by side in a cemetery in Portland. At the time, Asians could not be buried with whites. This was finally resolved later, after much disagreement [21].

1943: The Three Great Allies Issue the 1943 Cairo Declaration, the United States Abolishes the Chinese Exclusion Act

China: In November 1943, the heads of state of China, the United States, and the United Kingdom issued the “Cairo Declaration,” demanding that Japan return all the territories it had occupied in China since 1895. On September 9, 1945, Japanese troops in China (under the leadership of Yasuji Okamura) finally surrendered, bringing an end to a long and bloody war. He Yingqin, representative of the Chinese government and Southeast Asia Allied Forces, was there to accept the statement of surrender. The Chinese battlefield successfully occupied the attention of more than a million of Japan’s main forces, lessening the pressure on American and British troops and helping to secure a victory for the Allies [22].

On November 18, 1942, Chiang Kai-shek’s wife Soong Mei-ling arrived in America to seek treatment for an illness. In her short stay, she delivered many official speeches promoting the anti-Japanese war in New York’s City Hall, Madison Square, Wellesley College, Chicago Stadium, and San Francisco City Hall, as well as Hollywood. In 1943 she accepted an invitation to speak before Congress. Her elegant, lilting English and dignified manner charmed her to the American people immediately, leaving them with a warm impression of the Chinese people. Her speech is credited with helping to change the negative stereotypes about Chinese Americans and allowing them to garner sympathy and support [11, 22]. Soong Mei-ling’s visit also strengthened the alliance between the United States and China during the war, and she herself was instrumental in facilitating the abolishment of the Chinese Exclusion Act [23]. At a dinner party with several important members of Congress, she asserted her belief that the abolishment of the Chinese Exclusion Act would do much to boost the morale of the Chinese people.

Figure 13:1943– President Roosevelt and the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt accompany Soong Mei-ling in front of Washington’s tomb. Picture source: [23].

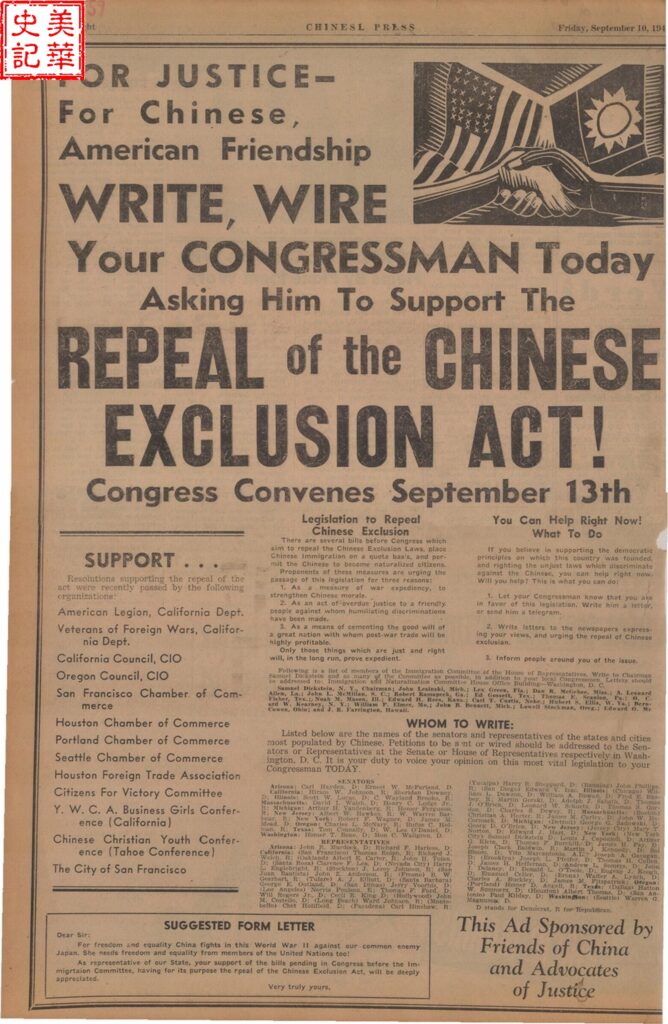

Prejudice against non-Western Europeans was still deeply ingrained in the American public, despite growing sympathies for the plight of China and Chinese people during World War II. To combat this specific problem, a small group of important public figures formed a private committee, the Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion. It was also known as the Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion and Place Immigration on a Quota Basis [24].

The committee sought to use their influence to persuade other organizations, the public, and Congress to abolish the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Among the committee’s famous members were author Pearl Buck and her second husband, prominent New York City publisher Richard Walsh [6]. The committee was relatively small (with a membership of around 240 people), but was instrumental in the abolishment of the Chinese Exclusion Act [6, 23].

Figure 14: Pearl Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973) won a Pulitzer in 1932 and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938 for her novel The Good Earth. She was a core member of the Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion, whose lobbying efforts successfully pushed for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Picture source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearl_S._Buck

Attempts to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act did not begin during World War II. Certain American missionaries had been calling for the end of Chinese exclusion since the 1920s, and Pearl Buck’s literary output during the 1930s, which introduced stories of the struggles of Chinese peasants, caused a sensation in the American public. In addition, Time magazine founder Henry Luce also spearheaded a campaign of sympathy for China. However, it was still the United States and China’s joint victory over Japan in the Pacific Theater that played the largest role in turning the tide of public opinion on Chinese people, enough so that repealing the Chinese Exclusion Act became possible [24].

On one side, the Japanese government raised the Chinese Exclusion Act as an example of American hypocrisy, which they used as an opportunity to promote Japanese imperialism. On the other side, Chinese diplomats maintained that the Chinese Exclusion Act lowered Chinese troops’ morale, negatively impacting the war efforts. The Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion supported public lobbying on moral grounds, arguing that American ideals of equality contradicted with the reality of anti-Chinese discrimination. They, however, also took advantage of the new military situation developing in the Pacific and insisted that repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act was a necessary measure to win the war [24].

The committee was composed mostly of American elites on the east coast and their allies, who utilized their social and professional positions to further the cause of the committee. For example, business groups involved with the committee lobbied in Congress, arguing that the exclusion and mistreatment of Chinese immigrants by customs officials was bad for business. They hoped that the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act would build stronger economic and trade relations between the U.S. and Asia after the war [24].

The committee first met on May 25, 1943, hoping to persuade a larger group of people to lobby with them to win more supporters in Congress. Only seven months after the committee’s first meeting, on December 17, 1943, President Roosevelt signed the Magnuson Act (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943) into law. Thus ended 61 long years of Chinese exclusion [25].

The Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943 was proposed by then-House member (later Senator) Warren G. Magnuson. The act allowed Chinese immigration for the first time in many years, and made it possible for some Chinese immigrants to become naturalized citizens. It was a notable step forward in relaxing racial and national immigration barriers, yet it still left much to be desired. Immigration restrictions on Chinese people were still stringent, allowing only a total of 105 Chinese entry visas each year. The Magnuson Act also continued to deprive Chinese Americans (some of whom were U.S. citizens) by law and de facto the right to property ownership. This persisted until 1965, when the Magnuson Act was finally fully repealed [26].

Figure 15:During World War II, Chinese Americans and their supporters campaigned to abolish the Chinese Exclusion Act. This ad appeared in the Chinese Press. Picture source: Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA).

Roosevelt considered the Magnuson Act highly important to the war efforts and promoting peace. China, as an ally of the United States, had long stood against Japan alone. Now that the United States and China stood together, the U.S. needed to do the much-needed work of abolishing the Chinese Exclusion Act in order to right the wrongs of history and dispel the clouds of Japanese propaganda [3].

Racism and Tests of Loyalty

China: Flying Tigers member Harry Lim was walking with his fellow soldiers on the Shanghai Bund when they spotted a group of Japanese captives walking toward them. This was the first time any of them had ever gotten close to “the enemy.” As they passed each other, they took note of the similarity in their appearances and ages. Lim later recalled that “Except for the uniforms, those boys could have been us.” This experience provoked uncomfortable questions within them– including, “How will people back home treat Chinese Americans?” [6].

Japanese immigrants arrived in the U.S. about 30 years after Chinese immigrants. Most of their history, at the time, was heavily affected by the prejudice and discrimination that Chinese Americans had faced.

In the San Francisco Asian community, there existed conflicts between Japanese and Chinese Americans based on economic interests, which were a kind of traditional method of controlling the development of Asian communities by encouraging them to fight amongst themselves for relatively small benefits [27].

In the 1930s, increasingly bleak economic and social prospects caused persistent worries for second-generation Chinese Americans. At the same time that the Great Depression bore down on their opportunities, Chinatown was also facing competition from Japanese Americans and ethnic groups. Japanese Americans owned most of the antique shops on the major tourist-frequented streets.

The Japanese invasion aggravated the already tense relations between Japanese Americans and Chinese Americans. Some Japanese American elites liked to characterize their business successes in Chinatown as an extension of Japan’s triumph in Asia. In response, Chinese Americans merchants framed their competitors as invaders, urging white tourists to boycott Japanese businesses [27].

In Seattle, Chinese Americans were generally not friendly to Japanese Americans, a problem that only got worse after the Japanese invasion. People stopped frequenting Japanese shops. Chinese employees of Japanese bosses quit their jobs, one after the other. Japanese American author Monica Sone once wrote, “I dreaded going through Chinatown. The Chinese shopkeepers, gossiping and sunning themselves in front of their stores, invariably stopped their chatter to give me pointed, icicled glares.” [1]

After Pearl Harbor, attitudes toward Chinese Americans experienced a drastic change. This change was reflected in the media, where Chinese people were portrayed as loyal friends and Japanese people were characterized as spies and saboteurs.

According to a Gallup poll, Chinese people were seen as hardworking, honest, brave, religious, intelligent, and practical people; while Japanese Americans were described with such terms as “sly,” “treacherous,” “cruel,” and “warlike” [6].

Most Japanese Americans had never killed innocent people in China. Like any other ethnic group, they were students, businessmen, laborers, and ordinary employees. The large-scale boycott of Japanese goods, however, naturally fostered the rise in anti-Japanese sentiment. Protest against Japanese goods spiraled into a protest against Japanese culture– anti-Japanese shows often promoted both the boycott of Japanese goods and culture [12].

The anti-Japanese invasion and boycott movements did not inherently encompass the “boycotting” of Japanese Americans as well, but it did much to contribute to the general anti-Japanese atmosphere at the time. Just like anti-Chinese sentiment in the late nineteenth century, this kind of anti-Japanese sentiment was the catalyst for much of the discrimination Japanese Americans would face in the coming years.

Many loyal Japanese Americans were discriminated against. For example, it was reported that a Japanese American man married to an American woman had been prevented from making simple purchases, such as vegetables and flowers. In another instance, a Japanese American child sustained broken ribs after being attacked at school [12].

Japanese Americans, whose loyalty was severely questioned during WWII, were flung down to the lowest level of the discrimination totem pole.

With the exception of Chinese Americans in Hawaii, most Chinese Americans enjoyed their short-lived status as America’s favorite minority, and said nothing of the trampling of other Asian Americans’ civil rights.

In order to prevent misunderstandings, Chinese Americans employed various methods to clear themselves of the accusation of being Japanese.

Chinese Americans started wearing badges to distinguish themselves from the Japanese. Joseph Chiang, a newspaper reporter, said that in order to make things easier, he would often attach a badge to his lapel reading “Chinese Reporter, Not Japanese Please.” [6]

Some Chinese Americans started carrying ID cards signed by the Chinese embassy. Others fastened pins that read “I am Chinese” to their clothing. Store owners utilized something similar, displaying the same slogan in their windows to ward off any would-be attackers [6].

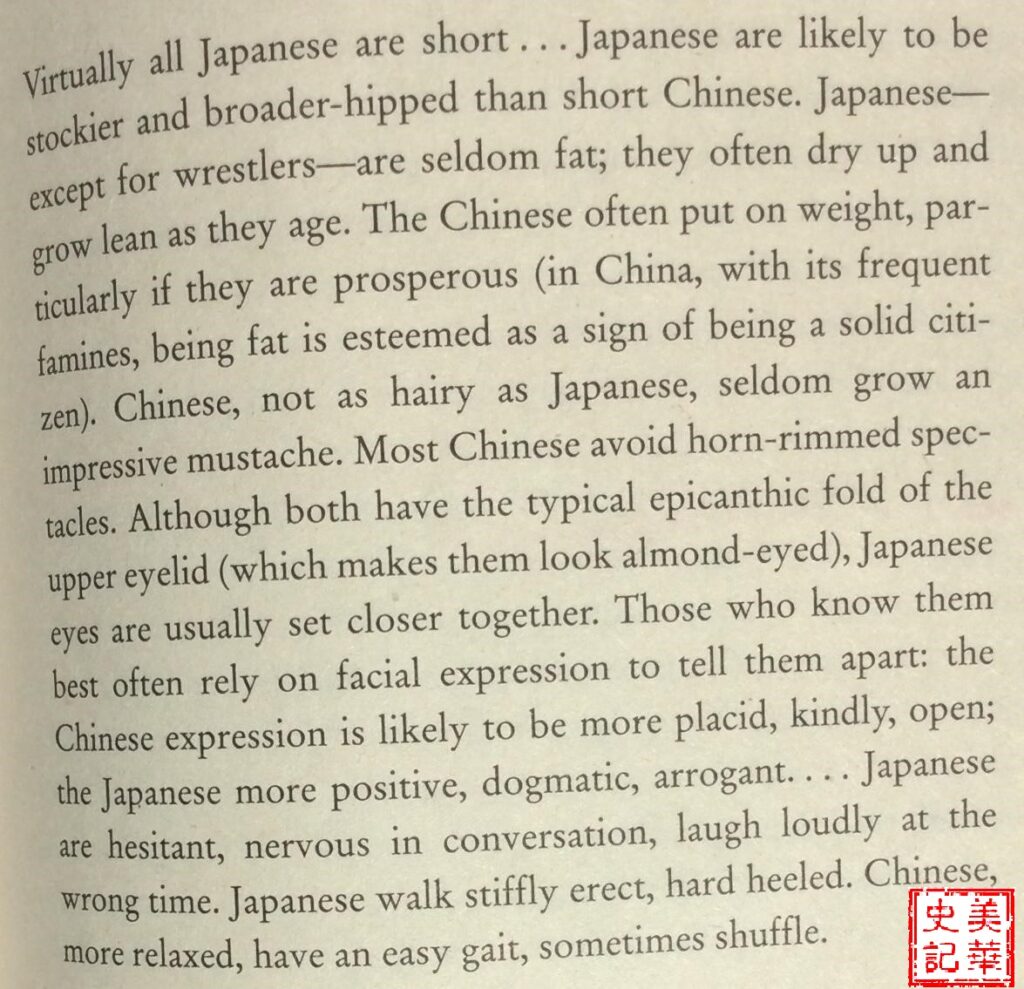

Chinese Americans took great pains to not be perceived as Japanese, but were other Americans really able to differentiate between Chinese and Japanese people?

Figure 16,Time magazine outlines the differences between Chinese and Japanese people. Source: [6]

White Americans ultimately did not care to differentiate between Japanese people loyal to the emperor, Japanese Americans, and Chinese Americans. In the end, all these different groups of people were lumped into one. In one instance, a Chinese American man, Han Yushan, rented a house in Beverly Hills in California. The neighbors called the cops repeatedly, claiming that he was a spy relaying information to the enemy. Chinese Americans in the military were also not exempt from race-related attacks. One Chinese American woman serving in the military recalled that a white man once yelled at her, “You damn Jap, get out of that uniform!” [6]

The similarity of the features which identifies one as East Asian, coupled with other Americans’ ignorance about the differences between Asian cultures, ultimately meant that harm intended for one East Asian ethnic group would land on all East Asian ethnic groups.

The rebound in racism facilitated the widespread rise in anti-Japanese sentiment. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were detained in internment camps.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Between the months of March and November in 1942, about 100,000 Japanese Americans– men and women, old and young, were “relocated” to internment camps from California to Arkansas. These internment camps were located in desolated, isolated areas– places where no one had lived before, and would likely not live thereafter. Ironically enough, though Pearl Harbor took place in Hawaii, none of the 150,000 Japanese Americans in Hawaii were ever detained [27, 28].

Japanese Americans are sent to concentration camps– the Chinese Exclusion Act is abolished. Discrimination and hostility cycle around again, this time with a new victim.

Around 300,000 Japanese Americans fought on the side of the United States during World War II. They proved their loyalty to their doubting country through bloody battle and sacrifice, sometimes of their lives [27]. For Chinese Americans, their never-ending struggle, and undiminished contribution to the country through 61 long years of expulsion and exclusion finally won them recognition.

Of the multitude of ethnic groups that immigrated to the United States, the Chinese and Japanese, the two ethnic groups that were generally at the forefront of “yellow peril” fears, tended to suffer more expulsion and discrimination. However, their bravery and sacrifice in the face of the fight against fascism confirmed their identities and loyalty to the United States, affirming their place in the country which they had spilled so much blood for.

Citations:

- K. Scott Wong, Parades, Pickets, and Protests. Chinese Americans on the Home Front. HUMANITIES, July/August 2007 | Volume 28, Number 4. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2007/julyaugust/feature/parades-pickets-and-protests

- Peter Kwong, Kusanka Miscevic. “Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Community.”(the New Press, New York, London, 2005): P190-193

- Judy Yung. Unbound feet: A social history of Chinese women in San Francisco. (University of California Press, 1995): p223-252.

- Rasmussen, Cecilia (April 12, 1998). “‘China’s Amelia Earhart’ Got Her Wings Here”. The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Aldrich, Nancy (September 12, 2013). “Katherine Sui Fun Cheung”. 20th Century Aviation Magazine. Lakeland, Florida. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Iris Chang, “The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (Penguin, 2003): P215-235.

- Zhao, Xiaojian (2002). Remaking Chinese America: Immigration, Family, and Community, 1940-1965. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3011-6.P60

- Gibson, Karen Bush (2013). Women Aviators: 26 Stories of Pioneer Flights, Daring Missions, and Record-Setting Journeys. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61374-543-4.P80-81

- Driscoll, Marjorie C. (April 1936). “She Will Wing Over China”. Popular Aviation. Chicago, Illinois: Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. 18: 249, 284. Retrieved 31 December 2016.P249

- Woo, Elaine (September 7, 2003). “Katherine Cheung, 98; Immigrant Was Nation’s First Licensed Asian American Woman Pilot”. The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 30 December

- 杨树标,扬菁,宋美龄传,浙江大学出版社。2010年。

- Chris Kwon,The Washington Commonwealth Federation and the Japanese Boycott of 1937-1938. http://depts.washington.edu/depress/washington_commonwealth_federation_japanese_boycott.shtml

- “WCF ask U.S. to Ban Japan Shipments,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 24 July 1937, p.1.

- “WCF asks Boycott of Japan Goods; Schwellenbach Urged For Court Post,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 7 August 1937, p.1.

- “Nine-power Treaty,” HowStuffWorks.com, 27 February 2008, accessed 20 May 2009, <http://history.howstuffworks.com/asian-history/nine-power-treaty.htm>.

- Albert Anthony Acena, “The Washington Commonwealth Federation: Reform Politics and the Popular Front,” unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, (Seattle: University of Washington, 1975), p.199.

- “Japan Aided In Invasion by U.S. Military Cargo,” The Sunday News (Seattle, WA) 14 August 1937, p.1.

- 抗战时期 台山五次沦陷, 2015. http://news.tsbtv.tv/2015/0831/41233.shtml

- Stanley Wilfred Lau, american air museum in Britain http://www.americanairmuseum.com/person/241699

- Chung-Hoon, Former Grid Great at Academy Still Winning Letters on Pacific Navy Team” by Laurie Johnston, The Honolulu Advertiser, 1945.

- First Chinese-American woman to fly for military died in fiery crash. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/first-chinese-american-woman-to-fly-for-military-died-in-fiery-crash/

- 王丰,宋美龄的美丽与哀愁, 现代出版社 2015

- Lon Kurashige, Two faces of exclusion, the untold history of anti-Asian racism in the United States. The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill, P110-111

- Charles F. Bahmueller,“Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion” http://immigrationtounitedstates.org/431-citizens-committee-to-repeal-chinese-exclusion.html.

- The Repeal Act Digital History http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=3&psid=48

- Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. “Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Statement on Signing the Bill to Repeal the Chinese Exclusion Laws.,” December 17, 1943″. The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara.

- Charlotte Brooks, The War on Grant Avenue: Business Competition and Ethnic Rivalry in San Francisco’s Chinatown, 1937–1942 Journal of Urban History 37(3) 311–330, 2011.

- 托马斯·索威尔 美国种族简史 中信中版社 2011年

ABSTRACT

World War II closely linked China and the United States together in the international anti-fascist alliance, during which China was portrayed as a friend and ally by the public media in the United States. Many Chinese Americans actively participated in the anti-Japanese propaganda and war. Not only did they survive the harsh domestic political environment of the exclusion period, but their “popular” role in the war also won them respect and sympathy.

With great love and deep sympathy for the Chinese people, Pearl Buck, among many other notable Americans, formed the “Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion”, whose political leverage was so influential that it successfully persuaded numerous organizations and members of the public to lobby Congress for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Finally, in 1943, Congress passed a new Immigration Act that ended the sixty-one-year old Chinese exclusion.