Author: Yu Beichi

Translated by Audrey Jiang

About the author: Yu Beichi (M) was born November 1927 in Taishan county, Guangdong province. Upon graduation from Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangdong, he worked in the Ministry of Labor in Beijing until his retirement. His family consisted of his mother, father, older brother, and younger sister. His grandfather had left in 1907 to work in America. His father, at 15 years of age, followed Yu’s grandfather to America, and afterwards, his older brother, younger sister, and other friends and relatives left in succession. Only he and his mother were left in China. After the establishment of formal diplomatic relations between China and the United States, the author’s son and daughter also left to study in the United States at the end of 1979. After his retirement, the author brought his mother and wife with him to America, thus reuniting the long-separated family. Yu spent 23 years in the United States before returning to Beijing in 2009.

Introduction: At the beginning of the twentieth century, the great Qing Empire of the east was bowing to the ravages of cresting popular discontent. The whole edifice seemed ready to collapse. In the coastal southeastern states of Guangdong, Fujian, and the like, masses of impoverished peasants streamed overseas to find a living. In a speech given on December 9, 1923, Sun Yat-sen once said: “The majority of our party is overseas Chinese. Why are there so many overseas Chinese? Because life on the mainland does not provide for them. They must seek a living overseas. From Hong Kong alone 400,000 to 500,000 a year have headed for Southeast Asia in the last twenty years, and they will only continue to increase and not decrease.”

Crossing the Ocean | Making a Living | Forging Five Generations of Entrepreneurial History

Aside from the aforementioned southeast Asian countries, there were also many people that risked their lives crossing the ocean to immigrate to America. According to historical records, in the reign of the Qing emperor Daoguang there were people from Taishan, Guangdong, that embarked on flimsy sailboats heading for the Americas. The Gold Rush and construction of the transcontinental railroad attracted yet more Chinese workers to the United States to find work.

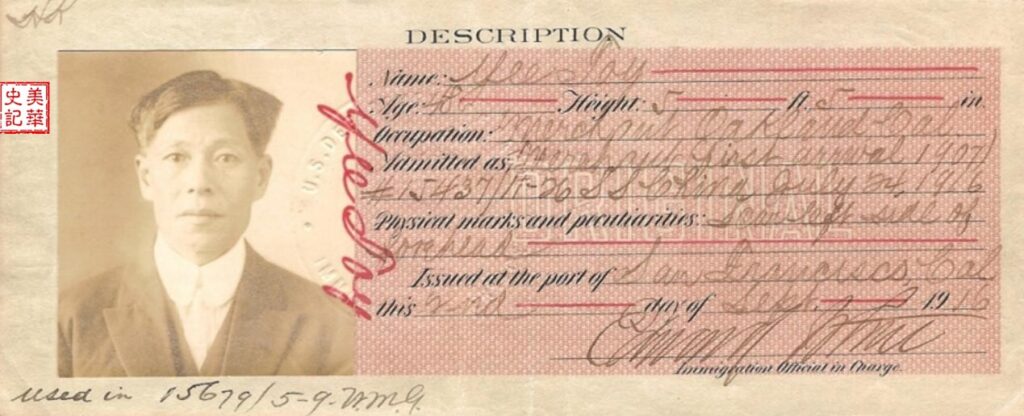

My grandfather Yu Shouhe was one of those plucky individuals. In China, he had less than one mu (an ancient Chinese unit a little less than 1/6 of an acre) of land to his name, barely enough to feed a family. In 1907 he set off from Taishan county in Guangdong province, all alone, to embark on a quest for a better life in America. The three-masted wooden ship he was on weathered all sorts of dangers and difficulties in reaching the United States. Afterwards, he gave rise to a five-generation family tradition of entrepreneurism.

Figure 1: my grandfather’s 1907 immigration certificate of identity

In that time, rural Chinese called the U.S. “Gold mountain,” as if the land was scattered with gold that anyone could pick up. This impression of the U.S. largely came from labor brokers. In reality, by the early twentieth century, the Gold Rush of the western United States had died down, and construction of the transcontinental railroad was already mostly complete. To new immigrants, who were unfamiliar with the land, unfluent in the language, and had no money on hand—people who, like my grandfather, had crossed oceans to get to America – how to survive became an urgent yet difficult problem to solve. The hardworking first generation of overseas Chinese looked to their personal circumstances, playing to their strengths and not their weaknesses. As a result, most of them opened Chinese restaurants and laundry shops. My grandfather was the same—after working in San Francisco for a while, he established his own laundry shop and moved from San Francisco to Detroit.

Because they had few options, the first generation of overseas Chinese unintentionally ushered in a century-long era of expansion of the Chinese restaurant and laundry shop. They offered valuable services to society while also solving many of their employment problems. Today, following the popularization of the home washing machine, the laundry shop industry has fallen, but the star of Chinese restaurants remains bright. However, as the education level and financial status of the new generations of overseas Chinese have risen, so has the number of Chinese people leaving the restaurant industry. Nowadays, many Chinese restaurants are owned and operated by Southeast Asians or other immigrants.

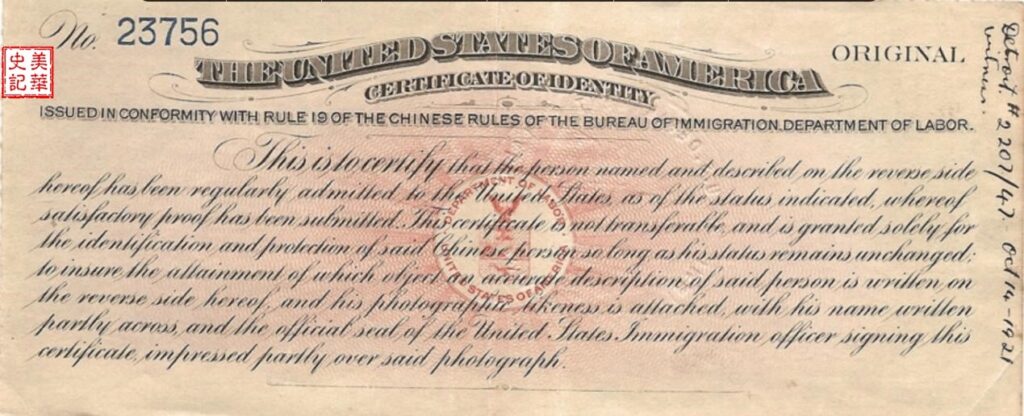

My grandfather Yu Shouhe was a generous, kindhearted man. Once he got on stable footing, he reached behind to help others. To later immigrants, no matter who had trouble, he was always quick to lend a hand. This was the reason why he was selected as a leader in the overseas Chinese community. He was close friends with another famous leader of the community, Situ Meitang (deputy to the first session of the National People’s Congress standing committee, member of the People’s Political Council and Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee, also invited to the founding ceremony of the PRC for his deeds). My grandfather and his friend were familiar names among the old generation of overseas Chinese. During the Sino-Japanese War, overseas Chinese, rallying behind the belief that the state of the motherland was everyone’s responsibility, came together to support China’s cause with an especial fervor. My grandfather was much the same, emptying his pockets to help fund the war effort. Situ Meitang, however, after journeying to China, lamented to my grandfather: “As an old friend, I have to tell you, most of our donations have landed in the hands of corrupt officials!”

Figure 2: My grandfather’s good friend Situ Meitang

Chinese Weakness | The Resulting Discrimination | Steadfast Patriotism

America is a country composed of immigrants, with a complicated racial and ethnic makeup. In the process of racial contact and mixing, it is inevitable that some friction, some collisions are going to occur. In the 20th century, the severest of these “frictions” was racial discrimination. At the time, due to the weakness of our country, overseas Chinese faced discrimination. Before entering the United States, Chinese people had to undergo a health inspection. With a ceramic bowl in hand, they each had to poop in it to certify that they had no hookworms. Only people without hookworms were permitted to enter the country. Europeans, however, only needed a certificate from a hospital in their home country to skip the health inspection. Initially, both Chinese and Japanese people could not skip the inspection. The Japanese were very dissatisfied with this state of affairs and formulated their own policies to retaliate. They mandated that every American undergo a comprehensive health exam before entering Japan. Americans, finding the procedures too cumbersome, agreed to drop the health inspections at each other’s borders. Chinese people, however, were unable to win equal standing in this area.

My father, Yu Yue, followed my grandfather to America at age 15. Upon arriving, he also worked in the laundry business, and would often encounter racism. One time a group of white teenagers came by, singing something like “chink chink Chinatown, eat dead rat.” My father, being young and hot-headed, was unable to tolerate this kind of treatment. He began arguing with the teenagers, and eventually it escalated into a fight. My father was injured, and the police arrived to deal with the situation. Knowing what they did, the white teenagers took the opportunity to flee the scene, and police promptly dropped the matter. According to my father, white Americans had derogatory names for each ethnic group—they called the Japanese “Japs,” and the Chinese “chinks.” There are two different narratives as to how the word “chink” came to be, and the first is that “chink” is a homonym of China’s Qing (qīng) Dynasty. The other is that “chink” developed from 请 (qǐng), a polite phrase that Chinese people liked to use. I lean toward the first explanation, because “chink” has a derogatory meaning, and at the time other countries disdained the useless, decaying Qing Dynasty.

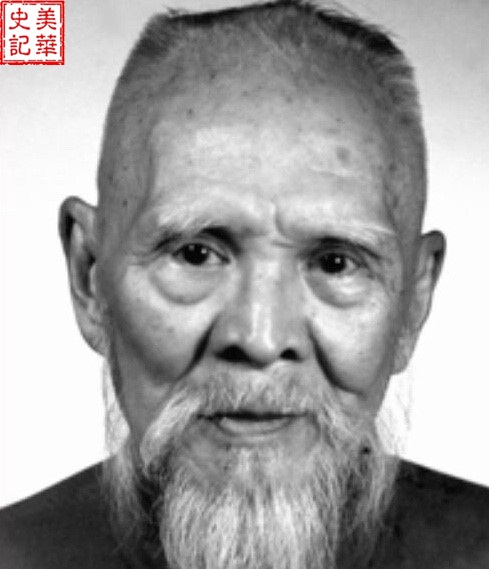

Before coming to the United States, my father had only ever received a few years of schooling at a small private school. After arriving in the U.S., my father split his time between working and his education. He was a diligent student, and was relentless in his studying. When he traveled back to China to marry, he enrolled himself in a correspondence school for traditional Chinese medicine, and devoted himself to researching it. Every time he returned to China to visit relatives, he would squeeze time to prepare various pills, powders, and ointments, turning the house into a pharmacy and providing free medicine and medical treatment to people from the same hometown. He even prepared the most valuable of medicinal materials—tiger bone, bear bile, deer musk, and rhinoceros horn, in case the need for them ever arose. Other times, he would hire people to carry prepared medicine from village to village, delivering them to people in need. In traditional Chinese medicine clinical research, he accumulated much valuable experience.

Figure 3, photos of myself with my parents, younger sister, and cousin in Taishan, Guangdong.

After my father returned to the United States, whenever he wasn’t working, he would help treat the illnesses of other overseas Chinese. People who knew him called him “doctor” (in the sense of a medical doctor but also an educated man). One time, another native of my father’s hometown traveled to China to visit relatives, but had to return before his wife gave birth because his ship ticket was set to expire. Not long after, he received a letter from home that said “the joy of the lintel” had arrived to their family. Unsure what this meant, the man asked many of his acquaintances, but they were unsure as well. Finally, he came to my father, who explained to him the origin of that phrase: In ancient times, there once was a man whose son had not managed to become an official, but whose daughter succeeded in marrying into the imperial family. As a result, a poem containing the line “the son is not appointed as an official, yet the daughter becomes consort/ you can see that the woman is the lintel of the house” (Note: the ornateness of a family’s lintel was indicative of a family’s status, so here the woman being the lintel of the house means that she is the family’s pride) was composed. Therefore, references to the lintel meant that a daughter had been born. The man was overjoyed, and thereafter would always come to my father with questions and problems. As a result, my father and the man became fast friends. My father once said that he led a hard and laborious life as a laundry washer, but he never regretted it. Serving as a doctor outside of work allowed him to improve people’s lives, which provided him much happiness and satisfaction.

China’s weakness resulted in overseas Chinese enduring much suffering and discrimination, but it also spurred them toward self-advancement and patriotism. During World War II, in order to defeat the fascists, protect democracy, and preserve peace, they offered up their strength and sometimes even their lives. At that time, to support the anti-Japanese war effort, overseas Chinese in the United States, in line with the principle of “those with money, give money; those with strength, give strength,” enthusiastically purchased war bonds. My father said he sometimes contributed as much as half his month’s income to buying war bonds. My uncle Yu Ziming even joined Chennault’s famous “Flying Tigers,” zipping through Kunming, Guiyang, and other destinations, charting a path from Myanmar to the Yunnan/Guizhou region, which facilitated attacks against the Japanese invaders and thus supported China’s war effort. Only after the surrender of the Japanese, did my uncle return to the United States with the “Flying Tigers.” During World War II, there were also some Taishan (our hometown) natives that enlisted in the army, who sacrificed their young lives in the battles clearing the outlying Japanese islands, right before the Japanese mainland. Their deaths are worthy of remembrance by future generations.

Figure 4: Chinese aviation bonds (to buy aviation equipment) that my father left behind

Self-improvement | The Courage to Participate | Building a New Home in Another Country

In 1936 my older brother Yu Beiyan followed my father to the United States. Upon arrival, he entered a Ford tech school. After graduation, he stayed in the Ford company, all the way until retirement. Some of his children, upon graduating from college, also worked for Ford. Others worked for GM, and yet others worked in jet engine research.

Prior to the liberation of China (the founding of the PRC), my older brother returned to get married. After the birth of his son, he and his wife were the only ones to come back to America. His son was to be temporarily raised by relatives in China. In 1949, after the liberation, my brother applied for an immigration visa for his not-yet-two-year-old son. His application was rejected, on the basis that immigrants from “red China” were not permitted. My brother was extremely dissatisfied with these unjustified laws, and so hired a lawyer to sue the INS (immigration and naturalization service). His civil lawsuit against the government was fought in the courts, until it caught the attention of then-president Truman. Finally, in 1950, Truman personally approved my nephew’s immigration visa. This lawsuit became a big piece of news—many American newspapers reported on it, greatly boosting the spirits of the many Chinese immigrants who had faced discrimination in immigration laws.

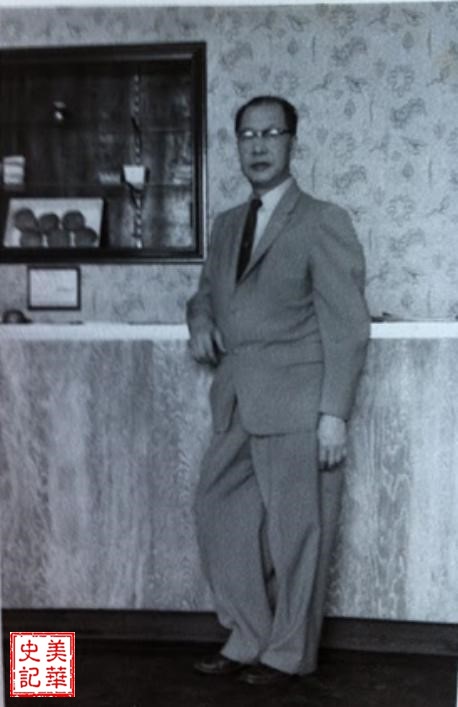

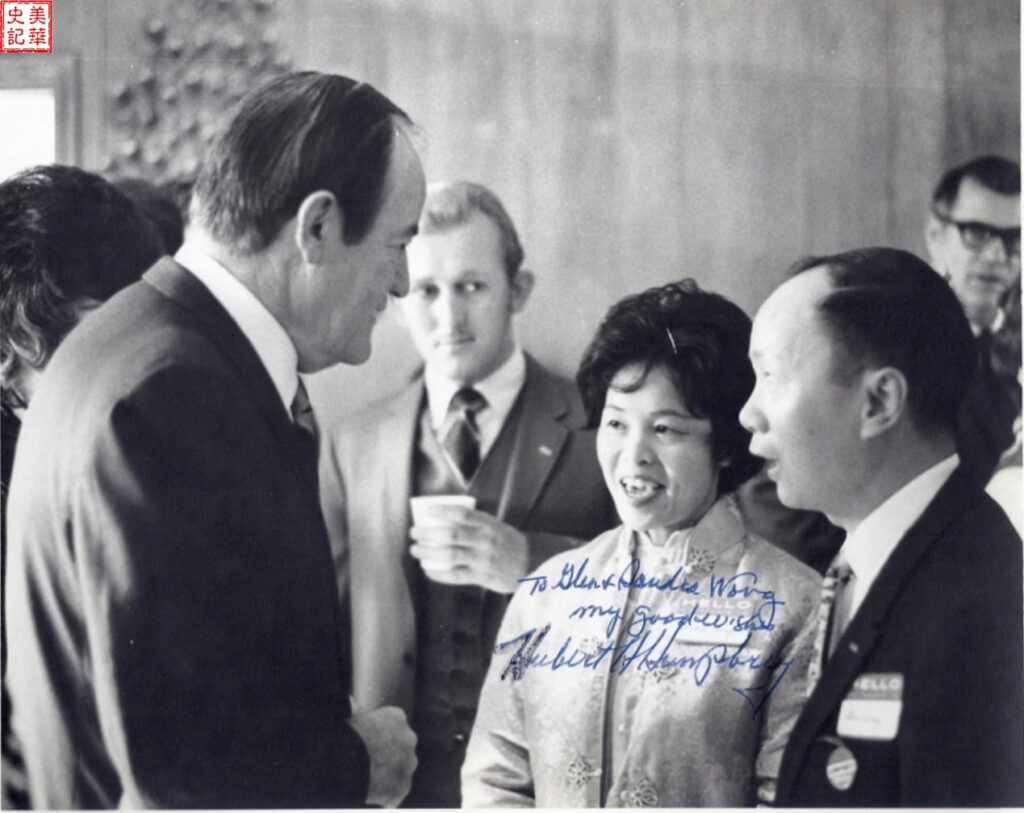

Figure 5: my younger sister and her husband conversing with Vice President Hubert Humphrey

My younger sister Yu Yunxian immigrated to the United States many years ago with her husband. Her husband’s family was also from Taishan. However, his family had been in the U.S. for generations, and my sister’s husband had even served in the Air Force when he was young. After leaving the military, he and his wife ran a Chinese restaurant in Minnesota, one of the first in the state. At that time, visiting Chinese organizations and local Chinese event-planning groups alike would often use their restaurant for their gatherings. In 1969, after a tornado caused serious damage to many residents’ houses and properties, my sister and her husband helped victims of the disaster by providing food from their restaurant. They were also enthusiastic participators in their civic duties, organizing Chinese people to attend the campaign events of political figures. They became friends with Minnesota’s then-senators (and later 38th and 42nd vice presidents, respectively) Hubert Humphrey and Walter Mondale.

Figure 6: my brother-in-law’s Air Force portrait

Cultural Integration | Preservation of Values | Stronger With Each Passing Generation

When I was close to graduation from middle school, my father sent me a letter, asking if I planned to come to America to work or to stay in China to study. I valued education, and had heard of the situation of overseas Chinese from my father and other relatives, and not wanting to experience discrimination, I decided to stay in China to finish my studies. In 1952, I graduated from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong and was assigned to the Ministry of Labor. Once I started, I continued for 34 years.

In the early ‘70s, as Chinese-U.S. relations improved, I finally reestablished contact with my siblings and relatives in America, and letters once again began to flow freely between us. With the resumption of the college entrance exams in 1978, my son and daughter qualified for the Beijing Institute of Technology and Peking University, respectively. At the invitation and funding of my sister, my son and daughter both arrived in America at the end of 1979 to study. They worked hard, overcoming the obstacles that the language barrier, culture gap, and life had to throw at them. Ultimately, they both graduated from the University of Minnesota with bachelor’s degrees in computing, and worked as software engineers in American companies and government departments.

Only after retirement in 1986 did I travel to America to reunite with my decades-separated family members. Although I was already in my sixties, I still experienced many of the various sweetnesses and bitternesses of Chinese American life. In my 23 years in America, I watched the place of Chinese Americans rise in society, far above the preceding generations. We also made quite a lot of American friends in our daily lives. Though they did not understand China deeply, they were willing to speak with us and learn more about China’s development and changes.

The Yu family in America is now quite a large family. From the old generation of immigrants, to the new, and even to the American-born-and-raised descendants; from my grandfather all the way to my children and grandchildren, as well as my great-nephew, the Yu family now spans six generations in the United States. Within a hundred years, this whole family has completed three major leaps: from farmer to laborer, laborer to technician, and finally from technician to high-tech professional. This process has been long in the making. One by one, the family’s fifth generation has moved on to establishing families and careers of their own, in fields as varied as the high-tech professional and the entrepreneur, doctors/nurses and administrators, artists and teachers, government agency workers, and private company employees. All of them, from each of their respective fields, have made active contributions to American society. Their generation has already begun integrating into mainstream American society. Among my relatives, there have been many examples of intermarriage with Japanese, German, and African peoples, which would have been hard to imagine for the previous generations. This new Yu generation, aside from possessing the American qualities of gregariousness, boldness in thought and action, and altruism, also inherited the Chinese values of thrift, hard work, resilience, respect for the elderly, and love for children, combining all of these traits into a new kind of American.

Figure 7: my daughter-in-law (right-hand side of the photo) hosting a local Chinese Spring Festival party