Author: Steven Chen

Translator: Pingbo Zhou

Abstract: One hundred and twenty years ago, who founded the first organization to fight for the protection of rights of Chinese Americans? Who traveled across the country giving speeches to advocate for the Chinese to have equal rights in America? Who wrote countless media articles exposing those who slandered the Chinese, and testified in front of Congress in opposition of the Chinese Exclusion Act? And who engaged in open debate against anti-Chinese politicians, and was even willing to duel to the death?

His name was Wong Chin Foo (Wang Qingfu), and he has been referred to as the Martin Luther King Jr. for Chinese Americans. This pioneer advocate for the protection of rights of Chinese Americans fought his entire life for Chinese Americans to be treated equally. He did not undertake this effort alone. In 1892, he founded and went on to lead the Chinese Equal Rights League. He fought unwaveringly against the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Preface

When Europeans arrived in North America, they referred to themselves as settlers or colonists, and believed that they were the owners of this new land.

When Africans were brought to North America as slaves, they were forced to accept their subservient status and acknowledge that they would not be treated the same as their masters.

When the Chinese came to America as “coolies” or contract workers, many of them saw themselves as foreign laborers and did not believe themselves to be a part of this country.

However, one man among them thought differently and was convinced that America should be a land of freedom and equality. He believed in and fought for the Chinese to have equal treatment and equal rights as other Americans. He often lost and suffered many setbacks, but he never gave up, and his actions eventually established the miracle of the protection of Chinese American rights. This man was Wong Chin Foo.

Early Chinese American History

The Chinese have over two hundred years of history in America, and the first historically recorded group of Chinese to arrive in the Americas came here in 1785[1]. The California Gold Rush that began in 1848 and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad from 1863 to 1869 drew large numbers of Chinese to come to America[1]. In 1882, prior to the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were approximately 100,000 Chinese living in America.

At the time, Chinese laborers were known as coolies. They received the lowest pay, did the toughest jobs, and experienced constant discrimination. Those that were fortunate managed to return to China with what little money they had earned. Those who were unlucky had to rely on companions to bring their remains home for burial. The ones who stayed in America often lived out the rest of their lives in poverty and loneliness.

Below are a few treaties and regulations that severely impacted the fate of the Chinese in America:

In 1868, China and America signed the Burlingame Treaty, establishing formal diplomatic and friendly relations between the two nations. The treaty required that both governments respect the right to immigration. However, before the ink had even dried on the treaty, America had passed the Page Act in 1875. The Page Act prevented Chinese laborers, and especially Chinese women, from coming to America. In 1882, America passed the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act, with a term of ten years. It effectively prevented the Chinese from immigrating to America and also prevented the Chinese who were already in America from becoming U.S. citizens. Ten years later in 1892, the Geary Act extended the Chinese Exclusion Act indefinitely and required the Chinese in America to carry an identification card at all times. If anyone was caught violating this rule, they would be captured and deported to China. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a sneak attack on the U.S. Navy base at Pearl Harbor. The next day, America declared war on Japan. At this time, America desperately needed China as an ally. Under these circumstances, President Roosevelt signed the Magnuson Act in December 1943, which officially terminated the Chinese Exclusion Act. By then, the Chinese Exclusion Act had already been in place for over sixty years.

Wong Chin Foo lived in America in the late 19th century, during the worst days of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

A Heaven-Sent Responsibility – The Chinese American Version of Moses

In Jewish legends recorded in the Bible, Moses was placed in the river in an ark after he was born. An Egyptian pharaoh’s daughter rescued him and raised him as an Egyptian. When Moses grew up, he led the Jews that had been enslaved in Egypt out of the country in search of the promised land. Wong Chin Foo’s experiences have several parallels to Moses.

Wong Chin Foo, who once went by Wang Huanqi and Wang Yanping, was born into a wealthy family in Jimo, Shandong in 1847. His father lost the family’s wealth due to his negligence, and father and son became beggars. They eventually arrived in Yantai. In 1861, the 13-year old Wong Chin Foo was taken in by a local American missionary couple, Landrum and Sallie Holmes. In 1867, Sally Holmes brought Wong to America to pursue an education. Wong Chin Foo studied at what are now George Washington University and Bucknell University[2].

Unlike many of the Chinese who arrived in America around this time, Wong Chin Foo had received an American style education since he was young. Mrs. Holmes hoped that Wong could be an evangelist and spread Christianity in China when he grew older, in order to save the Chinese people. While studying in America, Wong went and gave speeches in many cities, introducing audiences to Chinese culture. Everywhere he went, he was welcomed and respected as an exemplary Chinese. After graduating, Wong traveled to many places in the U.S. before returning to China in early 1871.

Upon returning to China, Wong did not become a missionary as Mrs. Holmes had hoped. Returning to Shandong as a 24-year old, Wong married Liu Yushan, a student and part-time teacher at a local missionary school. After this, he immediately went to Shanghai to work as a translator in customs, before moving to work for customs in Zhenjiang. Outside of work, Wong tapped into the influences of American culture and gave speeches in local communities, advocating for causes like breaking addiction to opium. He also formed social organizations in order to improve the morality of the masses. He promoted the beneficial aspects of American culture and customs and pushed for China to undergo social and cultural reform. Wong’s son Wong Fusheng was born in Zhejiang in 1873.

Wong Chin Foo formed an anti-Qing organization while working at Zhejiang customs and also used the opportunity afforded by his job as a customs official to purchase firearms from overseas. However, his plan was discovered by the Qing government. For this, Wong Chin Foo became a fugitive from the Qing dynasty and was forced to abandon his wife and son, fleeing to America[3]. Thus began his quest for Chinese Americans to receive equal treatment and have equal rights.

Aiding Chinese Women

On September 9, 1873, the steamboat that Wong had taken to America (the SS MacGregor) arrived in San Francisco. On the same day, the San Francisco police department received a mysterious secret letter, saying that there were Chinese women on the SS MacGregor that needed to be rescued[2].

In that era, the vast majority of Chinese in America had come as coolies or contract workers and had extremely hard lives. They were unable or unwilling to bring their families to America, and Chinese women were not useful as labor. This caused the ratio of Chinese men to women in America to be severely lopsided. In 1870, the ratio of Chinese men to women in California was eleven to one. These circumstances made brothels a lucrative industry. The brothels were often under the control of Chinese criminal organizations, which would bring willing or unwilling young Chinese women to America. There were such women on the ship that Wong arrived on, and it was he who had written the secret letter to the police. Because of Wong’s bravery and willingness to step in, a few women who had been forced into coming to America were rescued. Many American newspapers wrote about this event and Wong’s name gained widespread recognition[2].

The First Chinese American

Wong Chin Foo had already thoroughly demonstrated his skills as an orator when he was a student in America. People were willing to pay money to listen to him discuss Chinese culture, the current state of Chinese affairs, and his own experiences. The fame and recognition he immediately gained when coming to America for the second time made it easier for him to pursue a career in public speaking. Under arrangements made by his manager, he went from San Francisco to Michigan, giving speeches along the way. On April 3, 1874, Wong submitted his application for American citizenship at Grand Rapids, Michigan, and became a U.S. citizen that same day[5].

This was a groundbreaking event, because the vast majority of Chinese in America at that time did not want to become American citizens. Wong was one of the first Chinese to become an American citizen, and many American newspapers reported heavily on this event.

At the time, all Chinese in America were referred to as “Chinese”, regardless of whether or not they had obtained American citizenship. It was Wong who coined the term “Chinese American” in order to refer to Chinese people who had American citizenship. Wong encouraged those who were planning to stay in America for an extended duration to become American citizens, learn to speak English, cut off their queues, wear Western clothing, and make friends with those of other races.

In February 1883, Wong founded the Chinese American newspaper in New York City. This was the first Chinese-language publication east of the Rocky Mountains. Because of financial reasons, this newspaper was only in publication for seven months. In the coming years, Wong made many additional journalistic efforts[2].

Image 1: The Chinese American newspaper founded by Wong Chin Foo in New York City. (Source: http://www.firstchineseamerican.com/images/Figure%2015.jpg)

Image 2: Wong Chin Foo’s newspaper was based in this building on Broadway in Manhattan. (Source: http://www.kaiwind.com/culture/hot/201411/15/W020141115308361392554.jpg)

The Defender of Chinese Dignity

At that time, the majority of Americans had no interactions with the Chinese. In order to win support for Chinese exclusion, a group of people purposely slandered Chinese people and their culture, which caused widespread anti-Chinese sentiment. Wong Chin Foo wanted people to see and hear a Chinese person with their own eyes and ears in order to change their prejudices.

Wong made good use of the platform provided through his job as an orator in order to defend the honor of the Chinese. He traveled to major cities throughout the U.S. and even went to Canada to give speeches. His sophisticated manner, humorous rhetoric, and skilled English made him very popular. He gave countless speeches throughout his life – in 1876 alone, he delivered more than 80 speeches. Wong’s English essays were very popular as well. According to estimates, he published at least 192 essays in major American newspapers[6].

Wong’s speeches and essays introduced audiences to various aspects of life in China, including local customs and food. This helped his audiences gain a deeper understanding of the Chinese and erased preconceived notions and biases. One of the arguments to push for Chinese exclusion at the time was that the Chinese ate rats. Wong pulled out five hundred dollars and gambled: if anyone could prove that the Chinese ate rats, he would give them five hundred dollars. In the end, no one stepped forward. After this, Wong wrote an essay discussing a food that Chinese people actually ate: chop suey.

Having been raised by missionaries, Wong Chin Foo placed great emphasis on religion and was particularly opposed to the viewpoint that the Chinese were a people without faith, destined to go to hell after death. He believed that those who believed in Confucianism were the same as those who believed in Christianity, and could also go to heaven. In 1887, he wrote an essay that caused uproar across America, “Why Am I a Heathen”. He strongly defended the Chinese in the article, asking: Why is it that a kind Chinese person, who provides food for the hungry, who provides clothing for the cold, and who has never harmed another person in his life, must go to hell solely because he has never heard of Jesus Christ[5]?

Wong Chin Foo understood that in order for Americans to respect the Chinese, the Chinese also had to do away with certain bad habits. At the time, the gangs, opium dens, and brothels in Chinatown were heavily emphasized by Americans as an example of Chinese moral failings. Wong was willing to risk his life in opposition of these negative Chinese institutions.

No one is perfect, and everyone makes mistakes. As a product of the time he lived in, Wong Chin Foo had his own flaws as well. The Chinese laborers in America at the time primarily came from South China, especially Guangdong province. As someone from the North who was well-educated, and although he did his best to fight for the interests of all Chinese, Wong was unable to avoid having his own prejudices and biases towards Chinese laborers. At times he wanted to separate himself from them and their struggles. While opposing the anti-Chinese racism in American society, he would sometimes reveal his anti-Irish and anti-Black prejudices, which were very common among whites at the time.

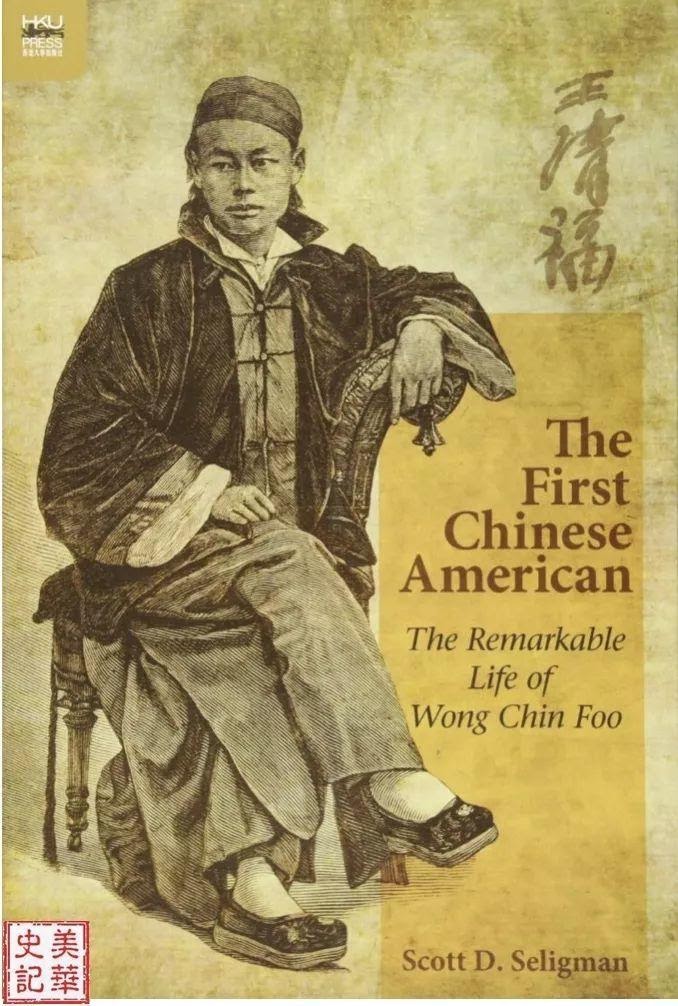

Image 3: A depiction of Wong Chin Foo. (Source: https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51acUxrrULL._SX336_BO1,204,203,200_.jpg)

Duel with Anti-Chinese Politician Denis Kearney

Both American political parties were not above slandering Chinese immigrants in order to win ballots and popular support. Yet the most ardent anti-Chinese voice belonged to politician Denis Kearney, who was of Irish descent[4].

Image 4: Anti-Chinese politician Denis Kearney. (Source: https://s22658.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/denis-kearney.jpg)

The Irish were among the first Europeans to arrive in North America. Between 1820 and 1860, America received two million immigrants from Ireland, of which 75% were fleeing the famine that lasted from 1845 to 1849. Many Irish immigrants came to California to pursue careers in mining or railroad construction, coming into direct competition with Chinese laborers. Denis Kearney of San Francisco was an Irish immigrant and an extremely impactful orator. He went to great lengths to depict the Chinese in a negative light and stir up anti-Chinese sentiment, ending each speech with “And whatever happens, the Chinese must go.” This became the loudest cry for Chinese exclusion.

Image 5: A print of the most popular anti-Chinese slogan, “The Chinese must go”. (Source: https://qph.fs.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-468194e737cc564b46a08f954d9d7cd2-c)

Kearney helped found the Workingmen’s Party of California, which made opposing cheap Chinese labor its primary objective. In 1878, this party controlled the California State Assembly and rewrote the state constitution, making it so the Chinese no longer had the right to vote or take part in the construction of public works projects in California.

Image 6: An anti-Chinese meeting in San Francisco. (Source: https://www.modernluxury.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/story-photo-with-inset-main/members_of_denis_kearneys_workingmens_party_riot_against_chinese_immigrants_in_san_francisco_california_in_1877.___prints_and_photographs_divisionlibrary_of_congress_washington_d.c._neg_no._lc-usz62-27754_.jpg)

In 1883, one year after America passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, Denis Kearney still went to the East Coast to drum up support for his anti-Chinese policies. When he arrived in New York, Wong Chin Foo challenged him via the newspapers, requesting a one-on-one open debate. After Kearney refused the debate, Wong challenged him to a duel. Kearney did not respond. Four years later, in order to win support for a law that closed a loophole in the Chinese Exclusion Act, Kearney came to the East Coast again. Wong once again challenged him to a debate. On October 18, 1887, Wong and Kearney engaged in an open debate which was widely reported on at the time. The majority of newspapers that reported on the debate believed that Wong won[2].

The Chinese Exclusion Act

In 1869, after construction ended on the Transcontinental Railroad, the majority of Chinese railroad workers needed to find new jobs. Their willingness to work for lower pay put pressure on workers of other races. This racial divide deepened when business owners replaced striking workers with Chinese labor. At the time, there were also a number of Chinese laborers who moved to the East Coast in search of work. Under these circumstances, the entire nation engaged in a debate over the Chinese Question. The anti-Chinese faction downplayed the contributions the Chinese had made for America, painting Chinese immigration as a threat to America’s economy and culture. The New York Tribune published a piece written by John Swinton, which comprehensively discussed the threat posed by the Chinese: 1. Business owners would use Chinese labor to gradually replace all other types of labor; 2. In order to compete with cheap Chinese labor, American workers would have to live in the same terrible conditions as the Chinese; 3. If the Chinese come to America in large numbers, they will change the racial makeup of the U.S., and the Chinese are Mongoloids, a lower race; 4. The arrival of large numbers of Chinese will change the American political landscape, bringing Eastern social norms into conflict with American democratic institutions; 5. The Chinese are dishonest and have no faith, they are heathens that carry diseases. These accusations formed the basis of popular support for the Chinese Exclusion Act. In this moment of crisis for the Chinese community, Wong Chin Foo paid no regard for his own personal safety and traveled across the country giving speeches and holding meetings. He refuted these baseless accusations intended to incite anti-Chinese hatred with reasoning and logic.

Image 7: Famous magazine cover that depicted the widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in the American west. (Source: http://americainclass.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Wasp-CapitalStocks.jpg)

Before the great debate over the Chinese Question, California and other states with relatively high Chinese populations had already enacted many state policies that were discriminatory against the Chinese. Prior to 1876, as the presidential election neared, both parties began considering enacting anti-Chinese legislation at the federal level in order to win more votes. At the time, there were less than 100,000 Chinese workers in America, representing less than 2% of the national population. These workers did not pose a great threat to the overall American labor market, but American voters worried that there would be mass increase in the amount of cheap Chinese labor. This motivated nefarious politicians to continually exaggerate the number of Chinese laborers, as well as their potential to increase. Wong Chin Foo debated: America did not need to worry about Chinese laborers significantly impacting the labor market, because there were only tens of thousands of Chinese workers. After working for a few years, these laborers would return to China. Those who remained in America would become Americanized and would request that Chinese workers be paid the same wages as other American laborers.

In 1878, in order to put America’s fears towards Chinese laborers to rest, the largest Chinese association in America (the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, CCBA, also known as the Six Companies) voluntarily suggested collecting a tax of one hundred U.S. dollars on every Chinese who came to America. This money would be used to pay for passage back to China. Wong Chin Foo strongly opposed this suggestion, believing it to be disgraceful to the Chinese.

On May 8, 1882, American president Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The law barred Chinese immigration for ten years and restricted the Chinese in America from becoming American citizens. This was the first law that explicitly targeted a certain race or ethnicity in American history. Ten years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended and made more severe, bringing devastation to the lives of the Chinese in both China and America.

The Geary Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act successfully prevented the Chinese from immigrating to America and also forced many to return to China. Yet the law could not negate the great demand for cheap Chinese labor in America, and some Chinese laborers were able to immigrate illegally. These illegal immigrants had little impact on the rapidly expanding American labor market, but after some politicians distorted the issue, they became a major worry for American voters. The Chinese Exclusion Act was due to expire in 1892 and Congress had to decide whether or not to extend it. 1892 also happened to be a presidential election year. California congressman Thomas J. Geary took the opportunity to propose the Geary Act. This law extended the ban on Chinese immigration for another ten years and added even more imposing requirements. Most objectionable to the Chinese was a requirement that all Chinese in America reapply for proof of residency and carry this proof with them at all times. Those who were found without acceptable documentation would be sent to do a year of hard labor before being deported. One of the requirements for the Chinese to apply for proof of residency was having two white witnesses testify on their behalf and confirm that they had been living in America. The vast majority of Chinese lived in Chinese communities, and this requirement was blatantly intended to make things difficult for them. (In Nazi Germany, only Jews were required to carry identification.)[7]

Image 8: A Chinese certificate of residence after the Geary Act was passed. (Source: https://hawkinsbay.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/certificate.jpg)

When the applications for proof of residency and warnings against disobeying were sent to Chinese communities, the Chinese were outraged. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association requested the Qing government to step in and simultaneously hired lawyers to challenge the Geary Act in court. They encouraged the Chinese to not apply for proof of residency; if any Chinese were arrested for not carrying identification, they would hire lawyers to take legal action and have them released. Wong Chin Foo joined in this battle as well, forming the Chinese Equal Rights League and organizing the “Thousand Man Rally” in New York on September 22, 1892 to protest the Geary Act. The protest was attended by many of other races as well. At the same time, the Chinese Equal Rights League lobbied members of Congress, urging them to overturn the Geary Act. In November 1892, they organized a 500-strong protest in Boston[2].

Image 9: Wong Chin Foo (left) giving a speech to an assembly in Boston alongside another leader of the Chinese Equal Rights League, Sam Ping Lee. (Source: The Boston Globe)

In addition to raising awareness through organizing meetings, Wong Chin Foo also did his best to find allies, including those who were friendly to the Chinese as well as those who did business with them. He built connections with clergy members, businessmen, public officials, and immigrants from other nations who worried that they would become the next target for exclusion and discrimination, collecting their signatures in numerous states including Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. John Forrester Andrew, a member of the House of Representatives from Massachusetts, helped propose a law to repeal the Geary Act and organized a hearing. On January 26, 1893, Wong Chin Foo testified before Congress in support of repealing the Geary Act. This was the first time a Chinese American had testified in a Congressional hearing and was reported on heavily by the press. Although the efforts to repeal the Geary Act were unsuccessful, the efforts of Wong and his allies forced Congress to modify how the Geary Act was enforced. Changes included removing the requirement for identification to have photographs, as well as only needing one white person to testify and confirm that a Chinese was a lawful resident (instead of two white witnesses as originally required).

Opposing the Geary Act may have been the largest act of protest by the Chinese in America. Nearly one hundred thousand Chinese risked deportation and refused to apply for proof of residency. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association hired a strong legal team and challenged the Act all the way to the California Supreme Court[8].

Encouraging Chinese Americans to Participate in Politics

Wong Chin Foo was no stranger to those who were part of the American mainstream and deeply understood the importance of political participation. He once cautioned Chinese Americans with voting rights: “When you don’t vote or don’t wish to vote, he (the politician) denounces you as a reptile; the moment you appear at the ballot box you are a man and a brother and are treated to cigars, whiskies, and beers.”[2]

Wong Chin Foo was good for his word, exercising his right to vote as a citizen and lobbying politicians. He also encouraged the Chinese to apply for American citizenship in order to win the right to vote and organized those who had the right to vote. In July 1884, Wong gathered “all” Chinese who had the right to vote in New York. Around 50 people attended the meeting. In order to build unity among the Chinese in the fight for equal rights, Wong formed the Chinese Equal Rights League along with Sam Ping Lee and Tom Yue in 1892. In 1896, he formed the American Liberty Party[2].

Returning to the Homeland

In the 25 years he spent in America, Wong tirelessly taught Americans about Chinese culture. He started Chinese schools to encourage Americans to learn Chinese and founded Chinese temples. In the World’s Columbian Exposition (World Fair) held in Chicago in 1893, there was a Chinese exhibit organized by Chinese Americans. Wong thought this was a good opportunity to both promote Chinese culture and make money. Thus, when he heard that the Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi International Exposition, another global exposition, was set to take place on June 1, 1898, he put all of his effort into organizing for that event. However, this was a massive and complicated event that required enormous financial support as well as collaboration from both the Chinese and U.S. government in order to import merchandise and recruit workers from China. The most difficult aspect was bringing in workers from China, which required special permission from the U.S. government. The U.S. government also required a security deposit – if the workers did not return to China on time, the deposit would be confiscated. Preparations for the event were disastrous and Wong was imprisoned at a crucial moment for unrelated reasons. His partners took the opportunity to remove him from their organization.

Ultimately, Wong Chin Foo was not able to see the Omaha exposition with his own eyes. On the eve of the opening ceremony, Wong had already boarded a ship that was heading from Los Angeles to Hong Kong. The purpose of this trip was to collect debts from his partners in Hong Kong, and more importantly see the wife and son who he had left behind for 25 years.

On June 20, 1898, the 51-year old Wong Chin Foo arrived in Hong Kong. Due to the turbulence of spending three weeks at sea, in addition to not being accustomed to Hong Kong’s humid climate, Wong fell severely ill. In just a few weeks, he had lost 20 pounds. His efforts to recuperate debts in Hong Kong were extremely unsuccessful and his health continued to deteriorate. On July 18, Wong left Hong Kong and headed home to Shandong, finally seeing his wife and son in Dengzhou. Yet this reunion was to be very short-lived, as Wong had to go to British-controlled Weihai out of fears that the Qing government would harass him. On September 13, 1898, Wong died of a heart attack. He was 51 years old[2]. The place he died, Weihai, was only forty miles away from the home of the American missionaries who had taken him in 37 years ago.

Image 10: Drawing of Wong Chin Foo. (Source: http://www.chinaqw.com/node2/node2796/node2883/node3175/images/0001863044.jpg)

Conclusion

In their darkest time, Wong Chin Foo devoted his life to fighting for the rights of Chinese Americans. However, due to the overwhelming prejudices that American society had towards minorities at the time, his efforts did not manage to bring about widespread support or sympathy from mainstream American society. Yet Wong was not intimidated, and his unwavering spirit set the example for future generations of Chinese Americans. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s finally gave minorities a chance to improve their political status. Starting in 1959, Chinese Americans started winning various elections for mayor, governor, House representative, and senator, among others. Years later, Wong Chin Foo’s dream has finally been realized. However, Chinese Americans still have a long way to go in terms of political participation and involvement, because we and our descendants have even bigger dreams.

Title: Wong Chin Foo -The Pioneer of Chinese American Civil Rights

ABSTRACT

Wong Chin Foo (1847–1898) was a Chinese-American activist, journalist, lecturer, and one of the most prolific Chinese writers in the San Francisco press of the 19th century. Wong, born in Jimo, Shandong Province, China, was among the first Chinese immigrants to be naturalized in 1873. Wong was dedicated to fighting for the equal rights of Chinese-Americans at the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Wong Ching Foo is deemed as the Chinese “Dr. Martin Luther King” because of his tremendous efforts and huge sacrifices to defend Chinese-Americans’ honor in that difficult time.

Afterword

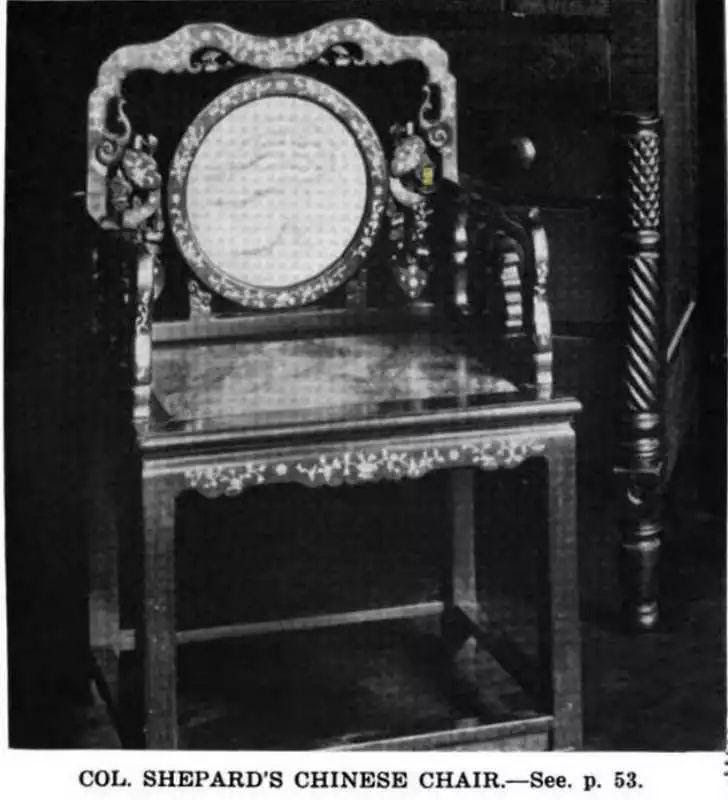

An artifact of Wong Chin Foo’s was recently discovered: After studying in America, Wong lived in China for three years with his wife and child and worked in customs. Because his scheme to oppose the Qing government was exposed, Wong had to flee for his life aboard a ship. In 1873, after receiving help from the Consul General in Yokohama, Mr. Shepard, Wong finally boarded a steamboat headed for San Francisco. Shepard’s family lived in Buffalo, New York. Twenty years later, Wong went to Buffalo to visit Mr. Shepard. Wong gifted Shepard a master’s chair made of black wood and marble. On May 1, 2019, we received confirmation from the Buffalo Historical Society: this chair is currently part of the Buffalo History Museum’s collection. The image description reads: Master’s chair gifted to Mr. Shepard by Wong Chin Foo. The photograph was taken over a hundred years ago.

Citations:

1. http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/collections/chinese-immigration-to-the-united-states-1884-1944/timeline.html

2. Seligman,Scott D.“The First Chinese American-The Remarkable Life of Wong Chin Foo”,Hong Kong University Press, 2013

3. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/riseind/chinimms/holton.html

4. http://www.firstchineseamerican.com/chronology.htm

5. Wong, Chingfoo, “Why Am I a Heathen?” http://www.firstchineseamerican.com/documents/Why%20Am%20I%20a%20Heathen,%20The%20North%20American%20Review,%20Vol.%20145,%20No.%20369%20(Aug.,%201887),%20pp.%20169-179.pdf

6. Wong, Chingfoo, speech from November 18, 1892

7. http://library.uwb.edu/Static/USimmigration/1892_geary_act.html

8. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geary_Act#cite_note-13