Author: Zhida Song-James

Translated by Audrey M. Jiang

Not long ago, The Washington Post released a report on the core values of America. In other words, what unites the divided peoples of America, scattered across thousands of miles and separated by race, class, gender, sexuality, and their personal experiences? At first glance, such a hodgepodge melting pot of people seems incongruous, chaotic– almost like they were hastily thrown together without a second thought– which, in a way, they were. The circumstances of history may have shoved these people together, but their little quirks and differences need not divide them– in fact, it could very well be a strength, as said by one young Utah mother: “One of the best things about our country is the diversity. I love being part of that… meeting people of different backgrounds and cultures and faiths.”

This story focuses on a girl, Ah Cum, left behind by her parents on the opposite side of the world. Throughout her whole life, she never once stopped exploring and expanding her horizons: exiting familiar circles and entering new ones, and as a result gained the richness and vibrancy that comes with a life well-acquainted with the diversity of the world.

Alone on the Other Side of the Ocean

The towering Sierra Nevada range separates the states of California and Nevada, both states whose growth was kick-started by the discovery of rich mineral goods. California, on the western side, is dotted with the remains of gold-mining campsites, evidence of the 1849 Gold Rush. On the east side lie the “silver mountains” of Nevada (where our story is set), which has made Nevada the biggest cumulative producer of silver to this day. In 1859 gold prospectors in northwestern Nevada discovered the Comstock Lode, a deposit abundant in high-quality silver. With that discovery sparked an influx of settlers, so much so that towns and cities seemed to spring up almost overnight. Virginia City, one of these mining towns, was once one of the largest settlements in between Chicago and the west coast.

Ah Cum was born in 1876 in Carson City, Nevada, with the surname Yee. Her father, Non Chong Yee, was a prominent figure in the Chinese community. At the time, Chinese immigrants made up about 23% of Carson City’s population [1], yet were prohibited from mining the rich ore fields. Instead, they turned to cutting and transporting lumber, establishing a formidable presence in the industry– in the ten or so years after 1870, nearly 70% of loggers were Chinese [2]. Lumber went hand-in-hand with the mining industry of the time, as square-set-timbering (a mining technique that requires a lot of wood) was widely used in the Comstock mines. Square-set timbering, invented by Philip Deideshiemer in 1860, allowed miners to tunnel deeper into the mountainside and safely retrieve deeply buried high-quality ore.

Non Chong Yee began his career as a simple logger and worked his way up to become a partner of one of the foremost Chinese American companies, Quong Hing and Company. He used the name Sam Gibson in the business world. No original records of the source of this name have been found, but historical data about the Chinese Americans of Carson City do indicate that he and his wife owned four properties in the Chinese district. Sam was fluent in English, and had close business relationships with major railroad and timber companies outside of the Chinese community. Aside from running his own business, he also worked as a labor agent, and took it upon himself to help non-English speaking Chinese laborers: finding jobs, signing contracts, paying taxes, etc. His kindness made him well known in the Chinese immigrant community as well as in the business world at large [3]. With such a family background, Ah Cum spent her childhood years happily, with nothing more to want for.

With the passage of 1882’s Chinese Exclusion Act, the situation of Chinese immigrants progressively worsened. In 1885, anti-Chinese mobs in Carson City unleashed a wave of boycotts against Chinese businesses to drive Chinese immigrants away, fires were also set to burn down the once-prosperous Chinese districts. Keeping a business as a Chinese immigrant became more and more difficult. Sam, afraid of losing his hard-fought wealth, decided to leave for his hometown. In 1885-86 he and his wife left for China, one by one. When they left, they brought Ah Cum’s two younger brothers with them, but left ten-year old Ah Cum in the care of family friends Hong Wei Chang and Bitsie Ah Too. Were they in too much of a hurry or did they have other plans? We will never know exactly; but what we do know is that Ah Cum was left alone on the other side of the ocean and never saw her parents again for the rest of her life.

The childless couple who took in Ah Cum ran a laundry shop in Bodie for a living. Bodie, at the lofty elevation of about 8000 feet, was a brand-new gold mining town at the time, but is now a historical park in California. During its heyday it was home to hundreds Chinese immigrants and had a Taoist temple in the area. In 1877 the Nevada school system allowed Chinese children to attend the public schools alongside children from other ethinic groups. Ah Cum’s adoptive parents sent her to a local public school, where she gained a mastery of English through her coursework and frequent interaction with other children. In her free time she would also do errands for their white neighbors. She familiarized herself with European lifestyles through such activities. Her interactions with other ethinic groups would form the basis for her reaching out to non-Chinese immigrant communities later on.

Two years later, Ah Cum and her adoptive parents moved to Hawthorne, Nevada, located southeast of Walker Lake. The city of Hawthorne was a railway hub to many nearby mines, and so attracted German, Irish, and Slavic railway workers, miners, mechanics, repairmen, and metal workers, who tended to come and go. Chinese immigrants, in turn, opened many shops and boarding houses to provide for these workers.

In 1890 fourteen-year-old Ah Cum married Chung Kee, a businessman twenty-eight years her senior. Chung Kee, born Gee Wen Chung, arrived in America through familial connections at an unknown date. Upon arriving, he worked in a relative’s shop. While in the U.S., he always used the name “Kee,” which came from the name of his shop. When Ah Cum married him, she took the name he most commonly used and so became Ah Cum Kee [4]. From their union, we can catch a glimpse of the marital situation of the average Chinese American of the time. In 1890, the ratio of males to females in the Chinese immigrant population was 33 to 1. Parents, with a multitude of choices, tended to want to marry their daughters off to established, well-off men who could potentially offer a higher bride-price. To achieve such levels of wealth, most men had to work for years, leading to a considerable age gap between couples. Chung Kee was the typical Chinese groom of that time– he had lived a comfortable life, and miners and railway workers of many different races all came to his shop to buy daily necessities.

Sixty percent of Nevada’s residents came from countries all over the world, due to Nevada’s laws regarding immigrants being quite lenient. Residents, regardless of nationality, race, or skin color could own the right to a piece of land for mining, and could buy, sell, or lease their mineral rights as they wished [5]. Chung Kee made his fortune in this business and eventually became a well-known figure in the area. The local newspaper, the Walker Lake Bulletin, even reported on his wedding and described Ah Cum as “a pretty little Chinese damsel who can read, write, and speak English like a native” [6].

The Female Farm Owner on Walker Lake

Snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada feeds the East Walker River, flowing northeast across the Nevada deserts. Hard-working, capable Chinese immigrants were the ones to utilize the river for dry farming– hence it is well known that “Chinese helped feed early Nevada” [7]. Dry farming anywhere is difficult, but the benefits were never felt more acutely as in a mining town, in the desert, in need of fresh fruits and vegetables. Thanks to the Kee family’s “Chinese Garden,” townspeople now had access to fresh tomatoes, beans, squashes and melons. As a result, Chung Kee became an indispensable figure in the community. After marriage, his family’s business expanded into restaurants and boarding houses for single workers. In addition to selling their produce, they also provided vegetables to restaurants and boarding houses, and the remainder would be canned for the off-season by Ah Cum.

During the windy spring season, Ah Cum and her husband were often seen planting seedlings together. She would then place jars over the young seedlings to prevent them from drying out. In the hot summer season, Ah Cum often brought her children out into the garden– weeding, catching insects; and in the short monsoon season, they collected rainwater for later irrigation of their plants. Sometimes, though, Ah Cum could be seen standing there, silently watching her children working and playing in the garden. Could it be that she was reminded of her own parents and brothers?

During this time, an entirely new group of people appeared in the Kee family’s life– the Native Americans living around Walker Lake’s shores. They belonged to the Paiute tribe, who had long roamed the regions of Arizona, Utah, and the southern parts of California and Nevada, hunting and gathering. After the start of the Gold Rush, large amounts of land were occupied by white settlers, and the federal government attempted to change the nomadic lifestyle of the Paiute by forcing them onto reservations to make a living by raising cattle or farming. The Paiute were not willing to accept this, and many of them left the reservation to find work, in timber industry and elsewhere. Others sold the pine nuts they gathered to white settlers, found that it actually was a profitable business, then made a living off of it. Over the years pine trees were cut down to make lumber for railroads and mining, grasses were cut by cattle ranchers, and the grass seeds the Paiute depended on for their livelihood disappeared. The destruction of the ecological chain also destroyed the last shreds of their way of living, and simply finding sustenance became the biggest challenge.

We do not know exactly how the Paiute came into contact with the Kee family, but we can guess that they might have come to the Kee store to buy daily necessities. According to historical records of Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), this kind-hearted Chinese American family, when they learned of Paiute struggles and poverty, began teaching them how to irrigate and cultivate the arid land. Upon learning how to farm, the lives of the Paiute improved greatly. The contributions of the Kee family were recognized in BIA records [4].

From 1893 to 1906, Ah Cum gave birth to six children. In 1909 the 62-year-old Chung Kee died and was buried in a small cemetery in Hawthorne. The responsibility for raising the children landed on Ah Cum’s shoulders alone. With her children, she continued to run the Chinese Garden, and when the farm got busy, she hired a few seasonal hands. The sale and delivery of the vegetables was handled by her oldest son, sixteen-year-old Charlie. Their most famous product was their stringless white celery. This celery was even sold to the kitchens of first-class hotels such as the St. Francisco in San Francisco and the Utah Hotel in Salt Lake City, and was also coveted by high-end restaurants all over the West. These establishments all praised the quality of the celery, saying that it was the most delicious and tender celery they had ever encountered, calling it “White Gold,” and “Nevada Sun.” According to the 1910 Census data, the land of the Chinese Garden was worth $1000, made even more impressive by the fact that Ah Cum was the state’s only female Chinese American farm owner [4][8].

In order to provide for herself and her children, Ah Cum continued to run the boarding house and restaurant businesses, and it was there that many of her customers got their first taste of Chinese food. Oftentimes European railway workers lined up for packed lunches before they went to work, and you could see Paiute people doing the same, but they often paid in herbs and nuts and other such goods instead of money. In return for the help from Ah Cum and her family, Paiute people would often take Ah Cum’s children into the reservation to fish. When they were done, they would send the children home with woven Paiute baskets full of the fish. Ah Cum would then cook the fish for her children and serve to everyone in the restaurant. At this time in her mind, the differences among white workers, Chinese farmers, and Native Americans did not seem important at all. Interactions with the Paiute also planted the seeds of knowledge of and respect for other cultures in her children’s hearts. Later on, the second daughter, Florence, played the daughter of a Powhatan chief, Pocahontas in her school [9]. Despite the fact that America’s indigenous peoples and the more recent wave of European and Asian immigrants were not truly sitting at the same proverbial table, the coexistence and mutual understanding of many different ethnic groups is emerging slowly out of daily life, little by little.

Bridging Between Cultures

Chung Kee, despite living in the United States, had always harbored plans of returning to his roots in his heart, and so maintained traditional Chinese customs in his home. For example, he frequently sent money back to his hometown Kaiping, and upon the birth of another child, he would send their name and birth date back home to fill in the genealogical records. The change came when their eldest son, Charlie (Ah Yuen), began to go to school. There were few Chinese immigrants in Hawthorne at the time, and when Charlie first went to school he still sported the traditional Chinese hairstyle and clothes. His “strange” appearance led to him being ridiculed by the other kids, which caused poor Charlie a lot of embarrassment. Seeing this, Ah Cum dressed him in Western clothes, just like the other kids. From then on, as her efforts to break the cultural barrier, Ah Cum’s children virtually adopted the same type of dress as their neighbors and used English names. Ah Cum wore similar long dresses as her white neighbors and spent her time planting flowers in the wooden boxes on the windowsill just like her neighbors did. Her English was fluent, her hand adept at baking, her husband had status in the community, and her female neighbors liked interacting with her. Though Hawthorne, with few Chinese Americans, could not give Ah Cum the same sense of belonging and the warmth of the Chinese community that she enjoyed during her childhood in Carson City, such interactions provided her some sense of community, and reduced difficulties to assimilate to or from other groups, as described by David Miller [10].

To maintain a farm in a desert as a woman, alone, is as difficult a feat as you would imagine. After the production of the mines nearby decreased, the Southern Pacific Railroad Company changed its routes, causing Hawthorne to lose its status as a railroad hub. The population dropped sharply. The boarding houses could not be sustained any longer. According to State tax records, Ah Cum was still in possession of a Hawthorne business license in 1913 [11]. Later on she moved several times around Hawthorne, Virginia City, Tonopah, and Reno, hoping to find a stable job and raise the kids. She leased out the farm, bought a house in Tonopah, and found a job as a chef at a Chinese restaurant. She also made some white friends there, the closest of them was Nellie Brissell. The owner of the restaurant, King Louie, had just come to US and still had a wife in China. The American-born Ah Cum did not intend to follow the Chinese tradition of staying faithful to one man forever, but she refused to marry King Louie under these circumstances, even though they had had a daughter, Nellie, born in 1917. She then left Tonopah and returned to Hawthorne. The Hawthorne that she returned to was only a sliver of its former glory: the railroads had shut down, the population had decreased significantly, houses lay abandoned, and all businesses struggled meagerly by. Ah Cum managed to scrape by for a while by employing Paiute people to tear down houses and selling the wood to a nearby mine, but it was not enough. In 1920 she left for Reno to live with some relatives of her parents. A single Chinese American mother with children, roaming the wilderness of the West, trying to find a place to settle down– you can’t help but feel moved, and in awe of her independence and courage.

Ah Cum Kee and her children [9]

Ah Cum’s pioneering spirit was reflected in her attitudes toward her children’s marriages. In 1914, in accordance with her husband’s dying wishes, she sent her son Charlie back to Guangdong province in China to find his bride. There he married a Chinese girl and had a son. However, the American born-and-raised Charlie had trouble adjusting to Chinese life and ended up returning to the United States by himself. From then on, Ah Cum realized that sending her children to China to find spouses was simply not a good idea, and did not require that they be married to ethnic Chinese only either. In 1915, her second daughter Florence fell in love with a young Basque man, Rudolph Espinoza.

On August 30, 1915, the San Francisco Chronicle, Carson City News, and Elko Free Press all published the same story: Florence Kee and Rudolph Espinoza married at sea. This story caught a lot of attention, as marriage between a Chinese American and white person was still illegal per an 1861 Nevada law [12], the same being true in California. This, however, could not stop the two young lovers. They found a ship captain who was willing to take them to international waters and marry them there. Upon returning to shore, the young couple were arrested. Interestingly enough, the eldest brother Charlie was against the marriage but the mother, Ah Cum, was not, she agreed to the marriage in defiance of law and tradition. The newlyweds were later set free by a kindly sheriff.

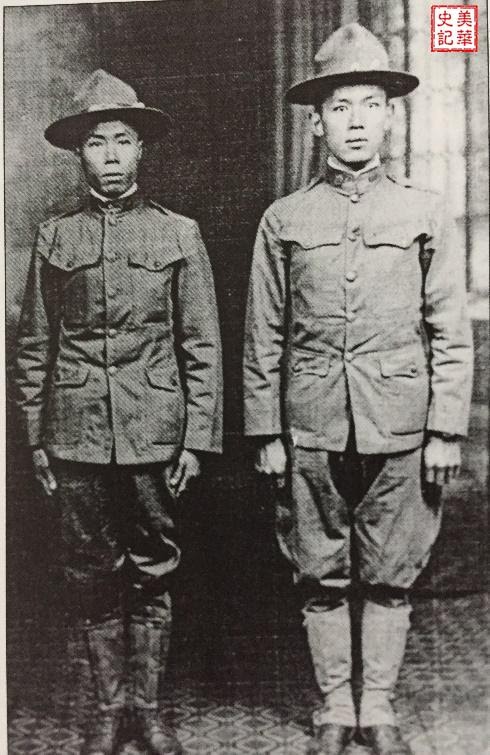

Charlie returned to the United States just in time for World War I. As one of the countries entering the war, the U.S. was working on expanding its armed forces. Charlie enlisted in the U.S. Army. Under his influence, his younger brother Willie and the sons of two of Ah Cum’s friends later also enlisted during World War II.

After 1920 Ah Cum lived in Reno, not far from her birthplace and once again in the midst of an established Chinese American community. King Louie later opened a restaurant and a Chinese medicine shop in Reno. Ah Cum often participated in various activities in the Chinese American community in Reno, and used her English skills to communicate with people of other ethnic groups. Her children once participated in an Independence Day parade wearing beautiful traditional Chinese clothes, catching the eyes of the town. After 1925 she followed her youngest son Frank to Oakland, California, and passed away there in 1929.

Charlie (left) and his friend in US Army [9]

As a child left behind by her parents, Ah Cum had a difficult upbringing; as a mother, she spent her whole life creating better opportunities for her children. In 1974 Charlie returned to his birthplace. The local newspaper, the Mineral County Independent, published a story on his homecoming [13]. From Charlie’s conversations and family documents [14], we can piece together the story of their family: before their father died, the entire family tried their best to maintain Chinese traditions, but they also kept in touch with other races and established good relationships with them. After their father died, Ah Cum led the children outside their little cultural circle, exposed them to the broader world, and urged them to accept “mainstream” lifestyle and culture. Eventually they integrated into the increasingly diverse United States. In this process, their perception of their own identity and society’s perception of their identity shifted from Chinese people in America to Chinese Americans. The most obvious evidence is demonstrated by her children, who, as soldiers, took the responsibility to defend their country.

All the places Ah Cum lived throughout her life

Notes and References:

- Guy Rocha:Myth #57: East is East, West is West and Where Was Carson City’s Chinatown Anyway? Nevada State Library Archives and Public Records, 2000

- Sue Fawn Chung: The Chinese and Green Gold: Lumbering In the Sierras, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, June 2003

- http://uncoveringnevada.weebly.com/wadsworth-1900-carson-city-chinatown.html

- Kriste Lindenmeyer ed, Sue Fawn Chung: Ah Cum Kee and Loy Lee Ford, Between Two Worlds, in Ordinary Women, Extraordinary Lives Women in American History , Wilmington, Delaware:SR Books. 2000

- Don Lynch and David Thompson: Battle Born Nevada, People History Stories, Carson City, Nevada:The Grace Dangberg Foundation Inc. 1994

- Walker Lake Bulletin, October 8, 1890

- Michael Lylel, “Chinese Immigrants Helped Build, Feed Early Nevada” in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, June 22, 2014

- Jan Cleere: Nevada’s Remarkable Women, Daughters, Wives, Sisters and Mothers Who Shaped History, Helena, Montana:Twodot. 2015

- Sue Fawn Chung with the Nevada State Museum: The Chinese in Nevada, Charleston, South Carolina: Acadia Publishing. 2011

- David Miller: On Nationality, Oxford:Clarendon Press. 1995

- Report of Stata License and Bullion Tax Agent. Appendix to Journals of Senate and Assembly, Vol 21 Part 2, Nevada Legislature, 1913

- Kathleen J. Fitzgerald: Recognizing Race and Ethnicity: Power, Privilege, and Inequality, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. 2014

- Mineral County Independent, September 25, 1974

- Kee Family Papers, University Nevada Las Vegas Library, Special Collections.

ABSTRACT

Ah Cum Kee (1876 – 1929) was a second-generation Chinese woman. At age ten, she was left behind when her prosperous parents decided to return to China when anti-Chinese sentiment swept Carson City, her birth place. When she was fourteen, she got married and moved to Hawthorne, a railroad hub where she became a homemaker and a restaurant/boarding house operator. With few Chinese people in her vicinity, Ah Cum not only intermingled with local European immigrant families but also befriended Native American Paiute tribe members. When her husband died in 1909, she continued to manage the family vegetable farm as the first Chinese American female farmer in Nevada.

Compared with her contemporaries, Ah Cum took an active role to assimilate into Euro-American society, and enjoyed the fruits of her efforts. She devoted her life to pursuing a brighter future for her six children, led them into different cultures, and encouraged them to engage in the mainstream society. Under her influence, a daughter bravely broke the inter-racial marriage barrier, and two of her sons joined the US army, fighting in both WWI and WWII. The path she trailblazed exemplifies the gradual but successful transformation from a Chinese person living in America to becoming a Chinese American.