Author: Fin Qi

Translator: Joyce Zhao

ABSTRACT

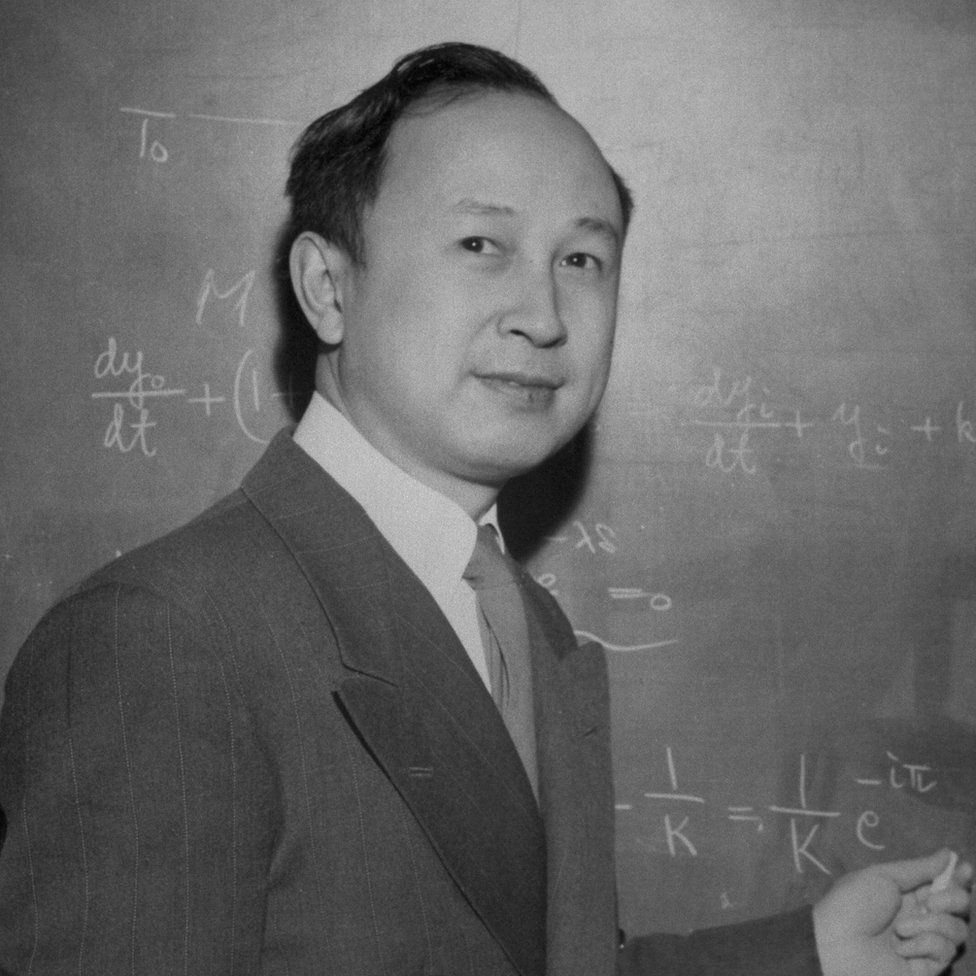

Qian Xuesen(Hsue-Shen Tsien) was a Chinese engineer and physicist who contributed to aerodynamics and rocket science in the United States. Recruited from MIT, he joined Theodore von Karman’s group at Caltech. In the 1950s, the US government accused him of communist sympathies and stripped of his security clearance. He was forced to return to China, but was detained at Terminal Island, near Los Angeles for over 10 days. After spending five years under the fight between the deportation order and house arrest, he was released in 1955 in exchange for the repatriation of American pilots who had been captured during the Korean War. Upon his return to China, he made important contributions to China’s missile and space program.

~~~

This article’s purpose is not to comment on Qian Xuesen as a person, nor does it detail his contributions to China in the latter half of his life. The author wishes to analyze the historical situation in America through the lenses of Qian Xuesen, refraining from praise or criticism, objectively portraying a scientist’s helplessness and struggles under the shadows of McCarthyism. He had dreams, troubles, and pride just like any other ordinary person. Even if that generation has already become a memory in history, the influences of McCarthyism have never disappeared from the ordinary people’s lives.

McCarthyism, are we a cold bystander?

Time is history’s best witness. Let us unfold the history of McCarthyism in America, observing the persecution and damage to the country it brought to innocent citizens through its emphasis on “loyalty”.

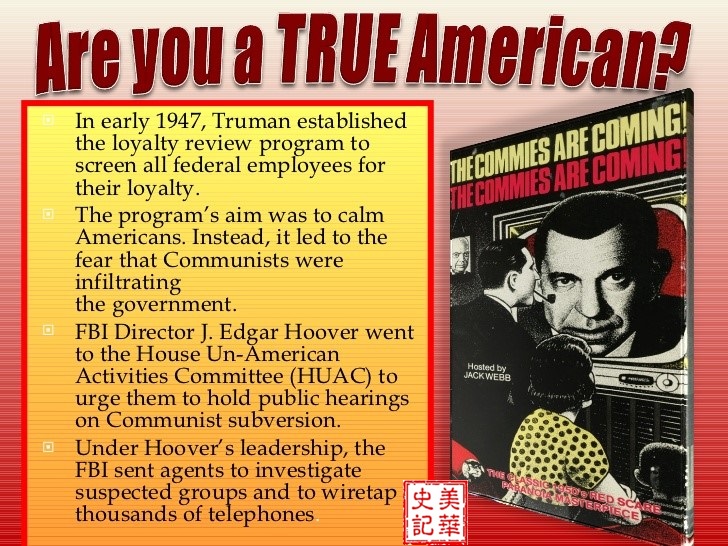

- In 1938, the U.S. House of Representatives created the “House Un-American Activities Committee” (HUAC), and it investigated for communist activities in the government, Hollywood film industry, and other departments.

- On March 21, 1947, President Harry S. Truman (1884 – 1972) signed into effect Executive Order 9835, also known as the “Loyalty Order”. It required the thorough investigation of loyalty amongst 2 million federal government employees. If there was “reasonable doubt” of loyalty, then the worker was fired. [1]

- In 1947, the Ministry of Justice announced that among 4984 “militant communists”, 91.4% had foreign blood. [2]

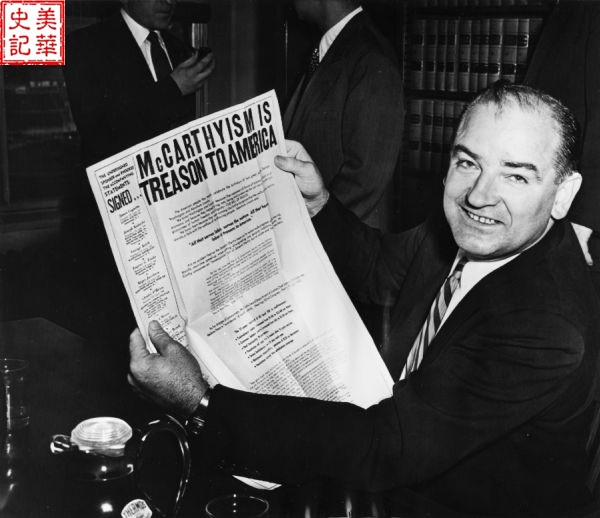

- In February of 1950, Joseph McCarthy, a senator of Wisconsin, gave a speech where he claimed to hold a list of 205 names who were communists working in the U.S. State Government. He accused celebrities, scholars, and anyone who held different political views of disloyalty, causing many to lose their jobs and suffer damage to their reputations. [3]

- The Korean war erupted in 1950-1953, which convinced many American citizens that the red communist ideology was dangerous to America. McCarthy and others fanned the fires of fear. [4]

Figure 1. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director J. Edgar Hoover led a “red” investigation. He began bringing “pro communist suspects” to Congress for questioning. He also created personal files for these people, wiretapping their telephones for supervision.

Figure 2. On February 9, 1950, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy entered the national stage.

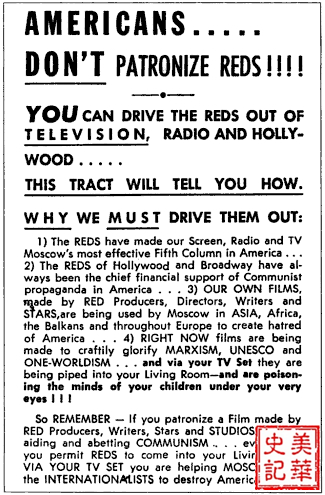

Figure 3. Anti-Red Leaflet. Anticommunist_Literature_1950s

Figure 4. U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy (hand covering the microphone) investigates red infiltration in the government. Byron Rollins/AP

In the ten years that the “Loyalty Order” was in effect (1948-1958), the FBI conducted name checks on 4.5 million people. If anything suspicious came up in these name checks, the FBI would then conduct a more thorough and comprehensive investigation. This type of comprehensive investigation was conducted 27,000 times. Around 5,000 federal employees resigned due to the result of such investigations, and 378 federal employees were fired on the grounds of “espionage activity”. Not only that, some local governments and even private businesses operated in a similar fashion, conducting “loyalty investigations” on their employees. [5]

Under the shadow of McCarthyism, Chinese Americans became dangerous elements. Many reporters and well-known Chinese scholars received calls from HUAC to undergo an investigation. Many Chinese organizations were on the list to be investigated, such as the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance (CHLA), China Daily News, Chinese Labor Mutual Aid Association, the American Democratic Youth League (Min Qing), the Chinese Student Christian Union (CSCA), the Association of Chinese Scientific Workers in America (ACSWA), etc. The reveal of the “paper sons” immigration scam brought danger to every Chinese. [6] Qian Xuesen (Hsue-Shen Tsien) was one of tens of millions of victims under the shadow of McCarthyism.

Figure 5. Qian Xuesen (December 11, 1911 – October 31, 2009).

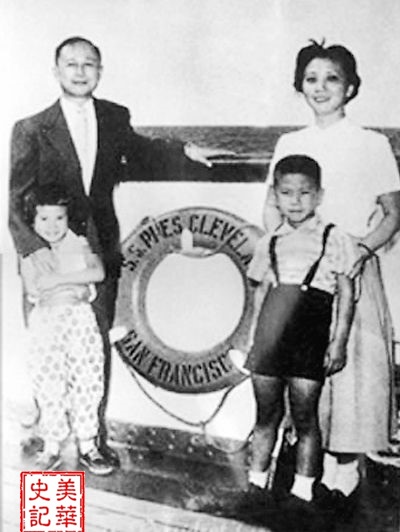

After the attacks of McCarthyism, Qian Xuesen left the port of Los Angeles on September 17, 1955. He bought 3 boat tickets, bringing his wife, Jiang Ying, his seven year old son, Qian Yonggang (Yucon, born in October of 1948), and his five year old daughter, Qian Yongzhen (Jung-jen, born on June 26, 1950). They boarded SS President Cleveland, leaving the country he lived in for 20 years, returning to his birth country — China, but called the People’s Republic of China under the communist party at the time.

Figure 6. Qian Xuesen’s family aboard the SS president Cleveland on September 17, 1955, leaving America.

Standing on the pier, Qian Xuesen told the reporters, “I don’t plan on coming back, and I have no reason to come back. I plan to do my best to help the Chinese people build up their nation to where they can live with dignity and happiness … I suggest you ask your State Department why… I have no bitterness against the American people”. [7]

The political persecution of “Chinese spies”

On June 6, 1950, the sky was filled with clouds. Two FBI workers went to Qian Xuesen’s office in the California Institute of Technology to ask him a simple question: if he was a communist.

Not only was Qian Xuesen not pro communist, he was exactly the opposite. He was married to Jiang Ying, the daughter of Jiang Baili, a high-ranking official of the Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek’s military adviser. Yes, in 1948, he once told a coworker at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that Mao Zedong might triumph over Chiang Kai-shek in China’s War of Liberation. However, this was only his speculation on the war during this time, and was in no way a representation of his support for the communist party.

Then how did he come to be suspected as a “communist”?

The California Institute of Technology gathered many of the top scientists of the world, so it is also a gathering place of free thought. Additionally, their work in defense pertains to national security, so it was easy to be caught in the influence of McCarthyism.

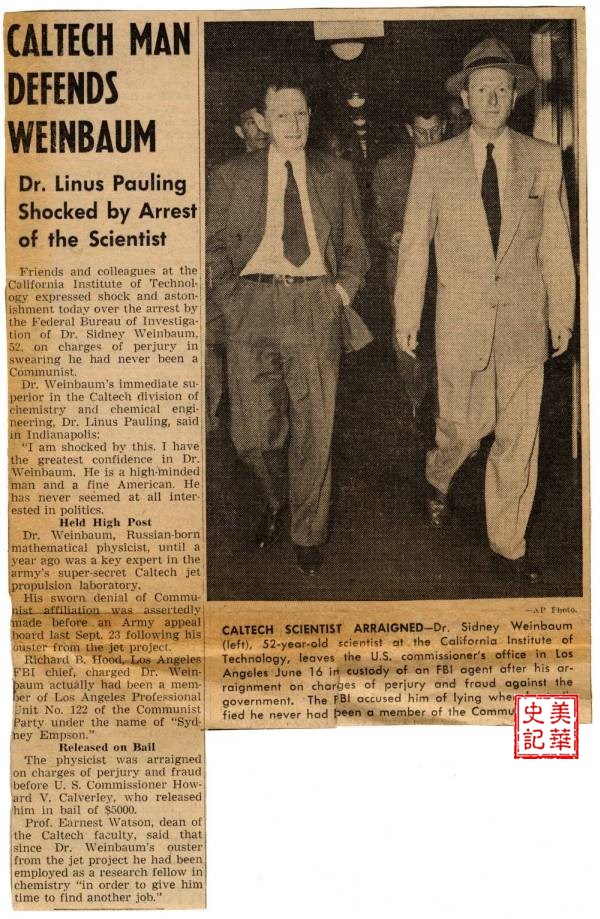

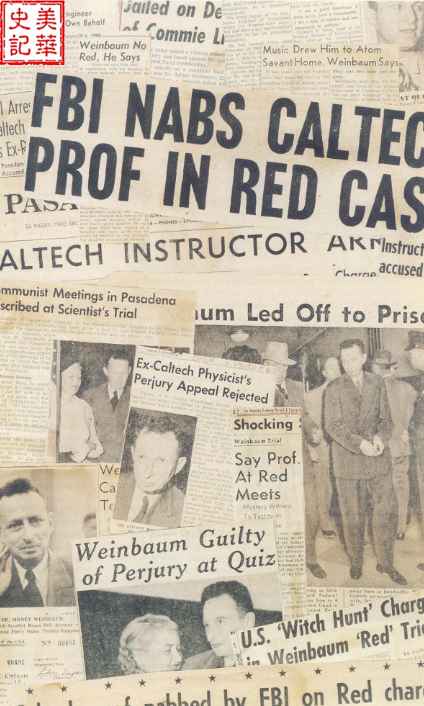

There’s a reason for this. During the war, the U.S. government intercepted a file in Paris that was a technical article written by Homer Joe Stewart, a scientist from California Institute of Technology’s department of aerospace. However, the FBI could not determine who was the spy. The first convicted was Sidney Weinbaum from the California Institute of Technology. The FBI claimed to have destroyed his organization. Weinbaum brought down many of his coworkers, including Frank Oppenheimer, Frank Malina, etc. [9] Qian Xuesen attended a social gathering hosted at Weinbaum’s house, which the FBI determined was a meeting of the Pasadena Communist Party. They said that Qian Xuesen’s name appeared on the 1938 member list under another name of John Decker. The FBI investigated the relationship between Qian Xuesen and Weinbaum. [10]

Qian Xuesen denied that he was a communist, stating that he does not support the communist party’s claims. He also didn’t believe that Weinbaum and other suspects were communists either. He told the FBI that he believed that his friends were loyal to the government. As a scientist, he believed that facts are used to measure one’s value or loyalty, but facts cannot test one’s loyalty or political views, and he cannot speculate. [10]

On June 16th, Weinbaum was arrested in his home. His arrest shocked his mentors, boss, coworkers, and friends. A lot of people gathered to write a petition to prove his loyalty to the country and gather funds to take his case to court. However, even after many appeared on court as witnesses, he was still sentenced to four years. After spending three springs and autumns in prison, because of his good behavior, he was released a year early. [11, 12]

Figure 7. The Los Angeles Examiner reports that Weinbaum, a 52 year old scientist from the California Institute of Technology, is arrested. July 30, 1950.

Figure 8. The arrest and trial of Weinbaum as reported in the local newspaper. From Engineering & Science/Fall 1991.

Because Qian Xuesen refused to concede and expose his friends, the U.S. government removed his clearance to participate in confidential research. All of Qian Xuesen’s complicated emotions bundled into one — anger, confusion, fear, and an injured self esteem. Two weeks later, he made a shocking decision to quit his position at the California Institute of Technology and return to China. [10]

When the FBI learned of this, they were even more confident that Qian Xuesen was a spy. They phoned Qian Xuesen to talk. On June 19th, Qian Xuesen repeated his reason for quitting his job at the California Institute of Technology to the FBI. He said, in the ten plus years he was in America, he always thought that he was welcomed, and he contributed greatly to science in America, especially during the war generation. Now, he no longer felt welcomed, and he didn’t have a reason to remain in America. [13]

In the beginning of July, Qian Xuesen wrote a letter to the International Trade Services Association, asking the association to help him book a flight to China from a Canadian airline. He planned to leave from Vancouver, boarding a plane to Hong Kong.

The president of the California Institute of Technology, Lee DuBridge (September 21, 1901 – January 23, 1994), requested Qian Xuesen to remain. He wrote to Washington, describing how Qian Xuesen was wrongly accused; he was an outstanding scientist. If America let him go back to China, the country would suffer greatly from this loss. [14]

On August 23, Qian Xuesen went to Washington to attend his hearing, attempting to clear his crimes. However, his heart was set on returning to China, and his flight was scheduled for August 28. On this day, just as Qian Xuesen was preparing to board the flight, he was stopped by a U.S. immigration officer. Actually, on August 25, the FBI had already confiscated the luggage he was shipping to China, which included 1,700 pounds of books and notebooks. This action was taken without Qian Xuesen nor his family’s knowledge. [14]

“Secret Data Seized in China Shipment!”

News quickly spread from Los Angeles newspapers to the headlines of The Times, Mirror, Examiner in a shocking article. The Associated Press and United Press International also spread the news throughout the nation, and it was reprinted through the New York Times and countless other newspapers.

A few months before, the media had still been praising the visionary Qian Xuesen — in the blink of an eye, he had become a Chinese spy.

Qian Xuesen’s American Dream

Before the persecution of McCarthyism, Qian Xuesen’s goals in life were all in America.

Even as a student, attracted by the idea of space travel, Qian Xuesen joined the “Suicide Squad” of the California Institute of Technology, a group of five students specializing in rocket research. The U.S. military quickly realized the importance of rockets and provided them with research funding. [15]

As an ally of the United States and a citizen of the Republic of China, Qian Xuesen obtained a clearance to conduct confidential research on classified projects. In 1945, he went to Washington as a consultant to the Department of Defense. He provided expert advice to the U.S. military during and after the war, and he provided the Pentagon with reports on the latest classified technology and its impact on the future. [16]

He contributed to the “Manhattan Project” that developed the first atomic bomb, and he helped develop the first American jet engine. [15,16]

On the European Victory Day (V-E day), he traveled to Germany with top American scientists to investigate German military technology and conduct technical interrogations with Nazi scientists. He interviewed rocket scientists Wernher von Braun and Rudolph Hermann.

As the business magazine Aviation Week pointed out in 2007, “No one then knew that the father of the future US space program [Braun] was being quizzed by the father of the future Chinese space program.” Qian Xuesen was determined as “Person of the Year”. [16]

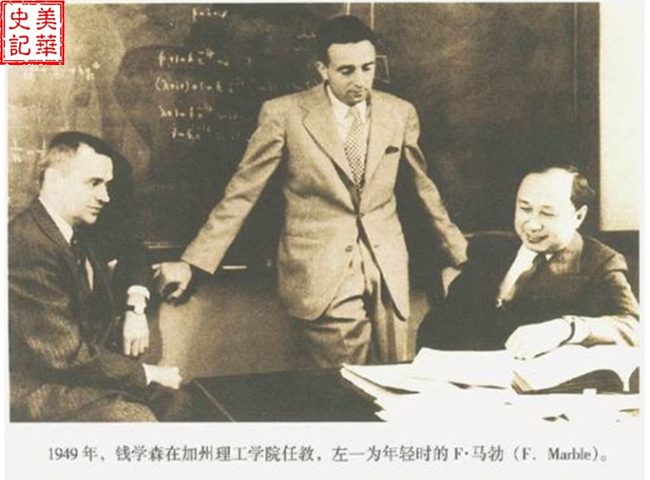

In October of 1948, Qian Xuesen chose to accept an invitation to the California Institute of Technology instead of Princeton. In 1949, he formally took up his post as the first director of the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Jet Propulsion Centre at the California Institute of Technology. [16]

In the summer of 1949, Qian Xuesen, his wife Jiang Ying, and his almost year old son Qian Yonggang (Yucon, born in October 1948), moved to Pasadena, California, where they planned to settle permanently. At that time, there were legal restrictions on buying a house in Los Angeles, and there were “covenant codes” for houses in certain affluent areas that prohibited residents from selling their houses to non-whites. Therefore, in June of 1949, Qian Xuesen and his wife Jiang Ying rented a 1940s house in the beautiful residential area of Altadena — a mahogany partition and a brick-timbered house surrounded by sprawling lawns and eucalyptus trees. [17]

At this time, Qian Xuesen’s career was flourishing, and he had established his position as a leader in this field. Qian Xuesen designed a rocket-like aircraft concept that could fly from New York to California within an hour. In 1949, the New York Times magazine excitedly reported this concept, which became well-known throughout the country. [15]

He occupied an important place in the rapidly developing U.S. rocket program and was one of the scientists who sent people into space. [17]

In 1949, he submitted an application for American citizenship! [18]

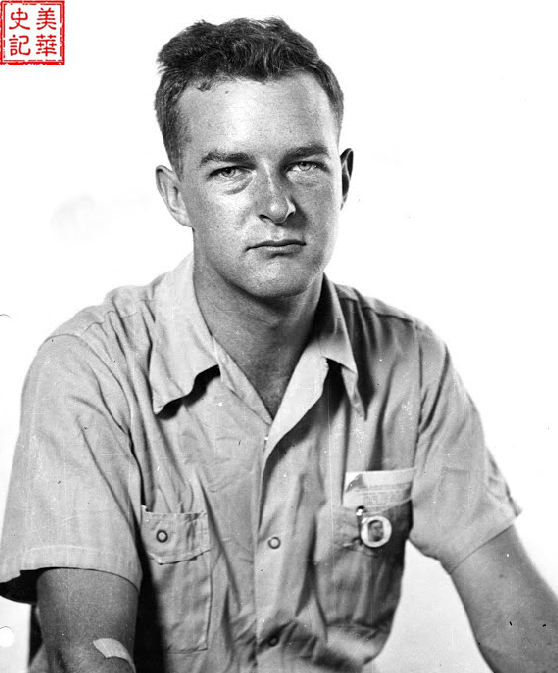

Figure 9. Qian Xuesen at the California Institute of Technology in 1949.

Although some people think that Qian Xuesen’s determination to return to China had long been set, his roommate Yuan Shaowen of the California Institute of Technology insisted instead that “Tsien had no intention of going back to China- Period! Ever! There were no facilities there with which to do research!He went back to China because he was forced to go!” [19]

On September 7, 1950, the Immigration Bureau sent two agents to arrest Qian Xuesen at his home. At that time, his wife Jiang Ying was holding the two-month-old baby girl Qian Yongzhen in her arms when she opened the door, and his son, Qian Yonggang, who was less than 2 years old, hid in a corner tremblingly. Qian Xuesen’s expression said, you are finally here!

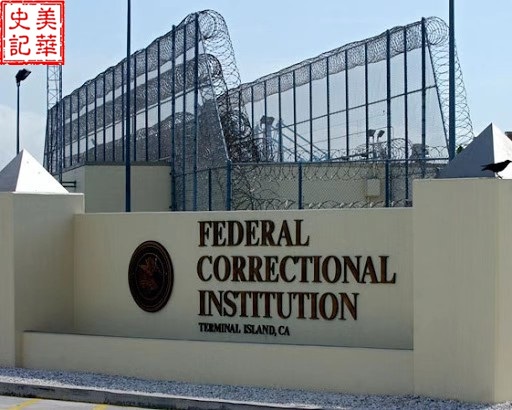

Qian Xuesen was temporarily detained in a prison on Terminal Island. On September 18, he was released on bail from the California Institute of Technology.

Picture 10. Terminal Island prison.

Many years later, when recalling this experience, he said, for more than ten days, I was detained. I was forbidden to talk to anyone. At night, the prison guards turned on the lights every 15 minutes, preventing me from resting. This ordeal caused me to lose 30 pounds in a short period of time. [20]

Although Qian Xuesen wanted to take root in the United States, like many Chinese Americans, he had always been proud of his Chinese identity. However, the political persecution of McCarthyism completely shattered Qian Xuesen’s American dream.

“Deportation Order for Subversion of National Security” collides with “Restriction on the Exit of Persons with Professional Knowledge”

In October 1950, the Immigration Bureau suddenly decided to expel Qian Xuesen from the country under the Subversive Control Act of 1950. Paradoxically, the U.S. Department of Justice prevented him from leaving because his technical research may be used by enemy countries for military defense. [21] Qian Xuesen was caught between two contradictory laws. The Immigration Bureau’s “Deportation Order for Subversion of National Security” collided with the Ministry of Justice’s “Restriction on the Exit of Persons with Professional Knowledge”. Since then, he embarked on a five-year journey to defend his rights.

As the journalist Milton Viorst wrote in Esquire in 1967, he was “free on bail but confined to [Los Angeles] county, not at liberty to go but not welcome to stay.” [15]

In order to clear the charge of “subverting national security,” Qian Xuesen worked with the well-known New York lawyer Grant Cooper to start a lawsuit against the Immigration Bureau.

At 10 am on October 11, 1950, a hearing was held in a small room at 117 West Ninth Street in central Los Angeles to decide whether to allow Qian Xuesen to remain in the United States. The focus of the hearing was Qian Xuesen’s loyalty to the US government.

Figure 11. Qian Xuesen, a scientist at the California Institute of Technology, at the hearing in 1950. On the left is the lawyer Grant Cooper. From the right is a trial reporter, the examiner Albert Del Guercio, and the hearing officer Ray Waddell. Los Angeles Times Photographs Collection.

They asked him: “In the event of conflict between the United States and Communist China, would you fight for the United States?” Qian Xuesen thought for a long time. Finally, he said: “My essential allegiance is to the people of China. If a war were to start between the United States and China, and if the United States war aim was for the good of the Chinese people, and I think it will be, then, of course, I will fight on the side of the United States.” Qian Xuesen repeatedly emphasized that he is not loyal to any political party, he is loyal to the Chinese people. [21]

Figure 12. Qian Xuesen and his lawyer Grant Cooper at the 1950 deportation hearing. https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/chinese-news-54702137

In early November, after two months of scrutiny, the U.S. prosecutors could not find evidence through the confiscated luggage, books, and notebooks that Qian Xuesen was a spy. His only crime was trying to transport technical materials back to China. Because the government believed that his original intentions were in good faith, he was exempt from any punishment.

It was not until April of the following year that Richard Lewis, a professor of chemistry at the University of Delaware, revealed that he had met Qian Xuesen at a gathering and believed that he was a member of the Communist Party. Lewis later confirmed that these allegations stemmed from great pressure from the Immigration Department. On April 26, 1951, the Immigration Bureau made a decision to expel Qian Xuesen from the country. [21]

Figure 13, University of Delaware (University of Delaware) chemistry professor Richard Lewis (Richard Lewis) was sued in federal court in Albany, New York. Picture taken from miSci- Museum of Innovation & Science. Creator: General Electric Company. Date Created: 1951-02-21

Attorney Cooper and the California Institute of Technology were dissatisfied with the verdict. They firmly believed that Qian Xuesen was innocent and were determined to appeal. In the following years, hearings were held repeatedly, and Qian Xuesen spent his life being questioned at any given moment. He was persecuted, and he lost his precious freedom.

By the end of 1954, under the contradiction between the “Deportation Order for Subversion of National Security” issued by the Immigration Bureau and the “Restriction on the Exit of Persons with Professional Knowledge” issued by the Ministry of Justice, Qian Xuesen had no way of predicting his fate.

He was subdued, depressed, and had no friends — only three small suitcases, ready to leave at any time.

If Qian Xuesen ever nursed the idea of continuing to work in the United States, or even becoming a U.S. citizen, it slowly disappeared over the years of battles in court.

China—U.S. diplomatic negotiations

In 1953, China and the U.S. reached an armistice agreement on the Korean War. The Operation Big Switch negotiations freed 75,183 prisoners to return to North Korea, 5,640 Chinese, 22,604 Indians, 7,862 South Koreans, 3,597 Americans, and 946 British. [22]

Figure 14. From August to September 1953, Chinese prisoners of war were transferred from the 765th Railway Transport Hospital to Mushan, North Korea. Photo taken by August “Gus” Firgau.

However, 155 American citizens were detained in China and 450 were missing. Beginning on June 5, 1954, Deputy Secretary of State U. Alexis Johnson held preliminary discussions with Wang Bingnan, secretary-general of the Chinese delegation, on this issue. The United States submitted to China a list of American citizens in China and U.S. military personnel detained by China, requesting that they be released back to America. Wang Bingnan also asked the United States to stop detaining Chinese scientists studying in the United States. There was no substantial progress in the four talks between the two sides.

In the following months, the US government assessed the background of Chinese students and scholars who were barred from returning home. Since World War II, more than 5,000 Chinese students had gone to the United States. They initially screened out about 110 scientists with technical knowledge that pose a threat to the national security of the United States. Among the 110 people, only two of them could not be released. One was David Wang who participated in the Nike Missile project, and the other was Qian Xuesen.

On April 1, 1955, Secretary of State Dulles submitted a memorandum to President Eisenhower recommending the release of these Chinese students and scholars in order to reach an agreement with China to release American prisoners. That year, dozens of Chinese students and scholars were allowed to leave the United States.

One day in June of 1955, Qian Xuesen escaped the surveillance of the FBI and sent a letter to the Chinese government, expressing his wish to return to China [23].

On August 1, 1955, in the famous Wang-Johnson talks, Wang Bingnan mentioned for the first time a request that surprised the United States — the release of Qian Xuesen. In exchange, China agreed to release 11 U.S. military pilots captured in the Korean War.

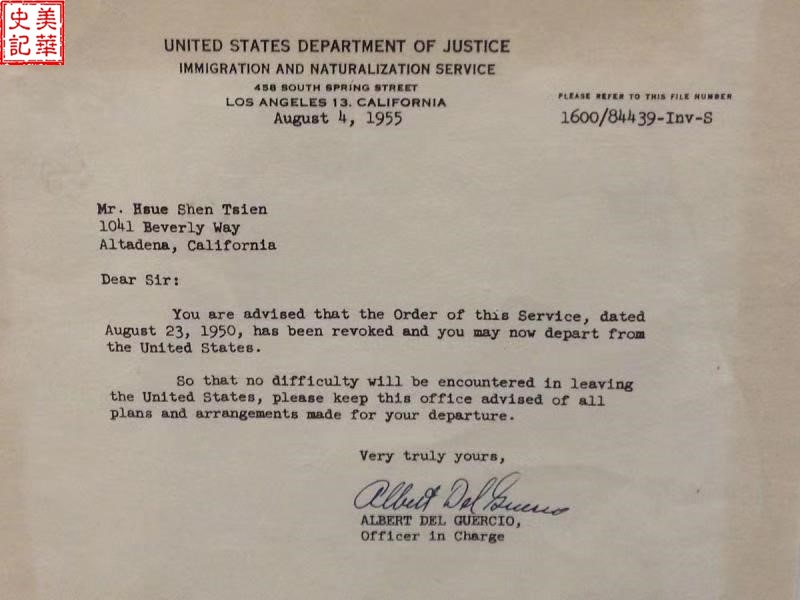

With Eisenhower’s approval, on August 4, 1955, Qian Xuesen received a notice from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), allowing him to return to China.

Figure 15. The notice from the USCIS that allowed Qian Xuesen to return to China.

This historic negotiation contributed to a win-win situation for China and the United States. In August 1955, China released 76 American prisoners, including 41 civilians and 35 military personnel. Except for 13 people, all the others returned to the United States in September 1957. China also received about 94 Chinese scientists who were educated in the United States. This number was half of the key scientists in China’s nuclear field at that time.

According to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, we had won back Qian Xuesen, and this was enough for negotiations. [24]

On October 8, 1955, the Qian family returned to China. In ten years, Qian Xuesen made indelible contributions to China’s aviation development.

• On October 16, 1964, China’s first atomic bomb was successfully detonated.

• On June 17, 1967, China’s first hydrogen bomb air-detonation test was successful.

• On April 24, 1970, China’s first artificial satellite was successfully launched.

On September 18, 1999, Qian Xuesen and 22 other science and technology experts were awarded the “Two Bombs and One Satellite Merit Award” by the Chinese government. Qian Xuesen was the most dazzling light in China’s field of aerospace science and technology.

Grant Cooper, Qian Xuesen’s lawyer, said: “That the government permitted this genius, this scientific genius, to be sent to Communist China to pick his brains is one of the tragedies of this century.” In the scientific community, many people agree with this view. [16]

U.S. Secretary of the Navy Dan A. Kimball claimed: “It (forcing Qian Xuesen to return home) was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a Communist than I was, and we forced him to go.” [25, 26]

References:

- https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/red-scare

- Peter Kwong, Dusanka Miscevic, “Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest New Community”, (The New Press, 2007), p216

- https://www.wpr.org/sen-joe-mccarthy-makes-first-accusations-week-1950

- https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/red-scare

- Ferrell, Robert H. (1994). Harry S. Truman: A Life. University of Missouri Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-8262-1050-0.

- Peter Kwong. p220-226

- Iris Chang. Thread of the Silkworm. BasicBooks. p199, 1995.

- Iris Chang. p141

- Iris Chang. p178

- Iris Chang. p149-150

- Iris Chang. p159

- Oral History, Sidney Weinbaum Politics at Mid-Century. Engineering & Science/Fall 1991. P31-38. Interview, August 15, 20, and 22, 1985, ARCHIVESCALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/664/2/Weinbaum.pdf. ARCHIVESCALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California.

- Iris Chang. p151

- Iris Chang. p154-155

- Tianyu Fang. The Man Who Took China to Space,March 28, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/28/the-man-who-took-china-to-space/

- Martin Childs. Qian Xuesen: Scientist and pioneer of China’s missile and space programmes. Friday 13 November 2009. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/qian-xuesen-scientist-and-pioneer-of-chinas-missile-and-space-programmes-1819724.html

- Iris Chang. p144-148

- Iris Chang. p143. Also, Declaration of intention to become a U.S. citizen (No. 329866 at U.S. District Court in Boston), April 5, 1949, National Archives, New England Regional Branch.

- Iris Chang. p195

- Iris Chang. p161

- Iris Chang. P166 – 171

- https://www.thatsmags.com/shanghai/post/1365/one-day-in-august_1

- Iris Chang. p182.

- Iris Chang. p184-190

- Perrett, Bradley; Asker, James R. (7 January 2008). “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen”. Aviation Week and Space Technology. 168 (1): 57–61. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Judith Goodstein, California Institute of Technology Oral History Project, “Interview with Lee A. DuBridge, Part II”, p31-35, 1981.

Unfortunately he became quite political since beginning the Culture Revolution. He bad mouthed several highly ranked people by making unfounded accusations in the letters to Mao and Mao’s wife.