Author:Xin Su

Translator: Ella N. Wu

My body, my choice, my rights! Ho Ah Kow, an early fighter for civil rights, won a rare lawsuit Queue Ordinance (or Pigtail Ordinance) of the 1870s. It added a touch of brilliance with Chinese imprints to the history of Americans fighting for civil rights.

Ho Ah Kow, a Chinese immigrant living in San Francisco, was arrested in April of 1878 on the basis of violating the Sanitary Ordinance. Thus Ho Ah Kow was subject to either a ten dollar fine or five days in jail. He chose the latter1,2 While in prison, he was forced to have his queue cut against his will, according to the “braid regulation”.

After Ho was released from prison, with the support of the Six Companies in San Francisco, he sued San Francisco Sheriff Mathew Nunan in federal court.3

Ho argued against the Pigtail Ordinance on the grounds that it violated his bodily autonomy and religious beliefs. According to Chinese religious beliefs, the cutting of hair was an act of sacrilege. Ho made it very clear to Nunan that he did not want to cut his hair on the basis of religious beliefs; however, Nunan ignored the plaintiff’s rights and forcibly shaved his head. Ho suffered immensely on a personal level, but he also suffered great shame in the eyes of relatives and friends, and faced rejection by his compatriots.2

The Sanitary Ordinance passed on July 29th, 1870 dictated that every person must occupy at least five hundred square feet of room to themselves. Failure to do so would result in $10 to $500 fines and/or imprisonment from 5 to 90 days.4

The law’s ostensible purpose is to prevent urban development from bringing about unsafe living conditions, but its essence was blatantly anti-Chinese. After the Gold Rush, many areas of San Francisco were overcrowded and overrun. The Sanitary Ordinance was only enforced in Chinatown. The ordinance was supported by the Anti-Coolie Association’s president Thomas Mooney and its vice president Hugh Murray. They represented the anti-Chinese sentiment in American society at that time. They use politicians and the media to spread dissatisfaction with the Chinese. White workers generally discriminate against Chinese people, believing that they have taken jobs that belonged to white people. The Chinese have become scapegoats for social problems. The excuse they found was that the sanitary conditions in the Chinese residential areas were poor, which affected the city’s appearance and infected diseases, and urgently needed to be rectified. With the help of politicians, the Sanitary Ordinance targeting Chinese people was introduced.4

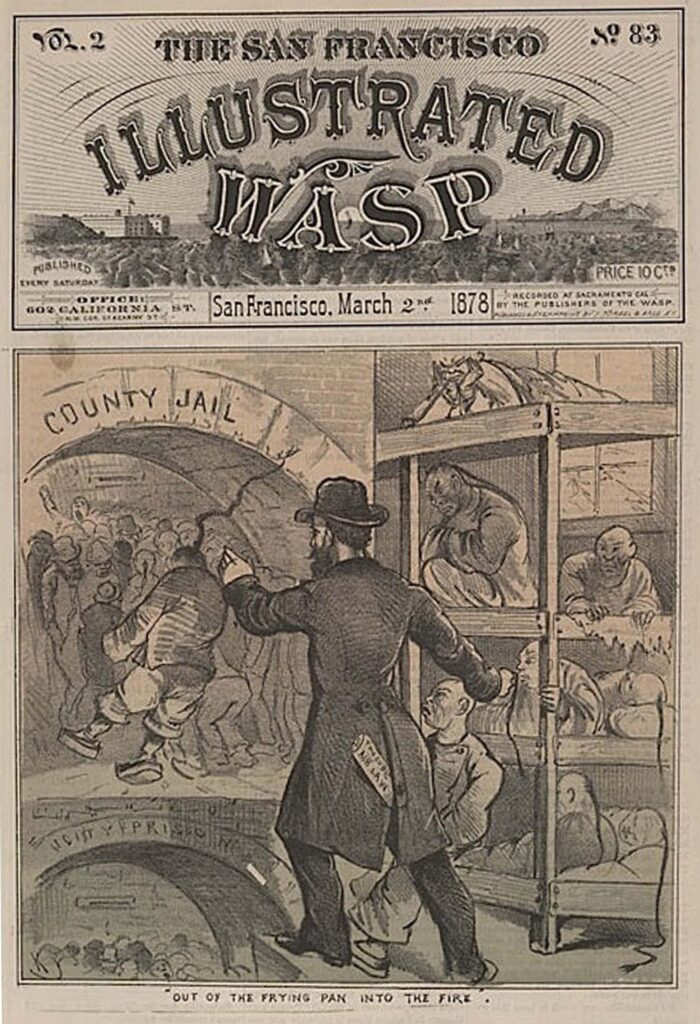

A large number of Chinese were arrested. Because they had no money, they were forced to go to jail. Ironically, the man who was jailed for living in a space of less than 500 cubic feet was being held in a 100 cubic foot prison. Eventually, the regulation had to be overturned due to prison overcrowding.3

Picture 1, The March 2, 1878 edition of the “San Francisco Illustrated Wasp”. The cartoon lambasts Sheriff Nunan for placing Chinese men arrested for violating the “500 cubic foot” law into a County Jail space of 100 cubic feet. Wasp (San Francisco, Calif.), F850 .W18, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The Pigtail Ordinance of 1873 was introduced alongside the Sanitary Ordinance imposed to target Chinese immigrants, forcing prisoners to cut their hair to an inch long.5 The Chinese immigrants chose jail time over paying fines when they were caught violating the Sanitary Ordinance, because they did not have money to spare. Prisons became more and more crowded. They couldn’t hold that many prisoners. To get around this, San Francisco officials began cutting the hair of Chinese immigrants in prison to force them to pay the fines instead.5

Furthermore, the San Francisco government decided they needed at least a surface-level reason to persecute the Chinese immigrants living there. They decided that the Pigtail Ordinance was going to be introduced to “prevent the outbreak of lice and fleas.” Masses of equal rights advocates have exposed the true purpose of the ordinance.6

The Ordinance was passed by the San Francisco Assembly in 1873 but immediately vetoed by Mayor William Alvord, who said, “This order, though general in its terms, in substance and effect, is a special and degrading punishment inflicted upon the Chinese residents for slight offenses and solely by reason of their alienage and race.”

Nonetheless, on April 3, 1876, the San Francisco Assembly passed the Ordinance, which was approved by Mayor Andrew Bryant.

Matthew Nunan, Chief of Police at the time, ran for re-election in 1877 as the Democratic candidate at the same time as Mayor Bryant. Both won the election.

Therefore, it fell to Sheriff Nunan to enforce the Pigtail Ordinance.

He was met by Ho Ah Kow, the Chinese civil rights advocate!

In April 1878, Ho Ah Kow sued officer Nunan. On June 14, 1879, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field commenced the trial.

The accused entered two pleas. He emphasized that according to the ordinance passed in San Francisco on June 14, 1876, every man’s hair was to be cut to under one inch while incarcerated in the county jail. He argued that Nunan was merely enforcing the law, which was well within his power and responsibility.

The plaintiff’s lawyer countered that the sheriff clearly exceeded his authority to enforce the law on these grounds:2

1. The Pigtail Ordance is not a health measure. If the ordinance considered only sanitary supervision, it would apply to all men and women, not just those who were to be trial or convicted.

2. Cutting hair is not a valid disciplinary measure. It would be absurd for the country to use hairstyles to regulate citizens’ behavior. How can the country regulate the hair style of outsiders? If not, is there a right to interfere with the way the prisoners are treated? In other words, in this fact, can one expand state power and criminal law? The notion that a prisoner can be manipulated and disposed of is very wrong and leads directly to abuse.

3. The state has no right to interfere and punish personal fashion as a crime. If men’s long braids are illegal, what about women’s curly hair and men’s beards? Can countries only decide people’s dressing standards according to their own arbitrary standards? Our answer is that the government interferes with things that have nothing to do with it and violates the rights of private individuals.

4. The short hair cut, like the striped clothing, is imposed on the prisoners of the state prison, partly to distinguish them from others so that they can be identified and captured after they escape. These coercive measures are reserved for felons. They are not applicable to misdemeanors. Forcibly shaving the hair of the Chinese goes beyond the government’s statutory powers.

5. Finally, the Pigtail Ordinance clearly violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,7 No person shall be deprived, without due process of law, of life, liberty, or property; nor shall any person be denied, within the jurisdiction of a State, the equal rights of the laws protection. This humiliating punishment is a special legislation for the Chinese as a single group.

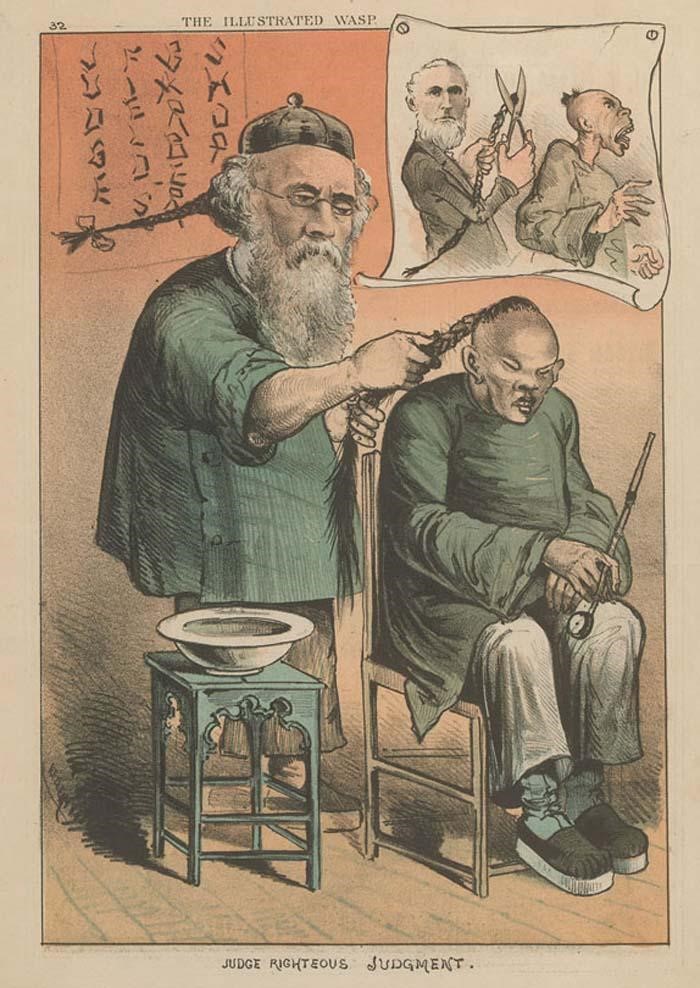

Despite loud opposition from the mainstream media and the public, Justice Stephen of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Pigtail Ordinance is unconstitutional and discriminatory, and therefore illegal. He cited the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The case of Ho suing Nunan concluded on July 7, 1879; He Ajiu won the case and received a huge compensation of 10,000 US dollars.

The court’s decision was “sickly sentimentality”, and stated that any concern for the “souless heathen [Chinese]” “absurd” and “altogether ridiculous.” reported by San Francisco Argonaut.

Picture 2, Under the caption “Judge Righteous’ Judgement” this “San Francisco Illustrated Wasp” cartoon depicts Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field in Chinese garb with a queue. Wasp (San Francisco, Calif.), F850 .W18, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Despite racist outcry over the outcome of case, the Chinese community rejoiced. They saw the hope of an equal society ruled by law rather than prejudice. Ho became a hero in the Chinese community, a humble little man who defeated the sheriff.

Conclusion:

Ho’s victory against Nunan was secured under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution which barred any unreasonable or unnecessary discrimination against different groups of people. Ho’s forced haircut was not only physical punishment, but humiliation and injustice. The violation of this Fourteenth Amendment right was aimed specifically at the Chinese. The Thankfully, the Ho Ah Kow case leaves us with confidence in the dignity of the Constitution.

About Nunan

Matthew Nunan was born in the county of Limerick, Ireland in 1828. Between 1845 and 1852, more than a million Irish poor, men, women and children died of starvation when Ireland suffered a devastating famine. Another million refugees left the country for their lives.3

At seventeen, Nunan joined thousands of Irish immigrants who fled to America. He reached New York City where he found a job on a farm near Lake Ontario, earning $10 a month. In 1854, Nunan became a U.S. citizen.

Enticed by the California gold rush, Nunan left the East Coast for California. Nunan worked mining in Nevada before moving to Michigan Bluffs in Placer County. Noonan and several prospectors made a fortune in a land claim.

In 1859, Nunan arrived in San Francisco. Not long after his arrival, he opened up a grocery store. In 1866, he sold his general store and purchased and operated a brewery, the Hibernia Brewery.

Nunan had always been politically active, a member of the San Francisco Volunteer Fire Department and an officer in the state militia.

In 1875, Nunan, who was still managing his own brewery, ran for sheriff as a Democrat, defeating the current Sheriff William McKibbin by 1,315 votes.

At that time, the sheriff’s term was two years, and his annual salary was eight thousand dollars. Nuna’s tenure as sheriff coincided with a strong anti-Chinese sentiment in California.

In 1876, a new San Francisco mayor, Andrew Bryant, signed the Pigtail Ordinance into law.

In 1877, Mayor Bryant and Sheriff Nunan, both Democratic candidates, secured re-election. Enforcement of the Pigtail Ordinance fell to Sheriff Matthew Nunan and his deputies.

The Ho v. Nunan decision was delivered by Supreme Court justices on July 7, 1879, a few months before the end of Nunan’s second term.

Nunan, caught up in the midst of a controversial anti-Chinese protest, decided not to run for a third term. During this time, the rise of the Workers Party in California was reshaping the political scene in San Francisco. Cal Workers candidate Thomas Desmond succeeded Nunan.

Nunan refocused on his brewery business, which continued to grow. He remained very active in civic affairs in San Francisco and founded a bank. He died at age 87 in his home at 452 Oak Street on January 7, 1916.

References:

- Case No. 6,546, Circuit Court, D. California

12 F. Cas. 252; 1879 U.S. App. LEXIS 1629; 5 Sawy. 552; 13 West. Jur. 409; 20 Alb. Law J. 250; 25 Int. Rev. Rec. 312 - Ho Ah Kow v. Nunan, Accessed December 3, 2022, http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Ho_Ah_Kow_v._Nunan

- Sheriff Matthew Nunan and the Chinese Queues, Accessed December 3, 2022, http://www.sfsdhistory.com/eras/sheriff-matthew-nunan-and-the-chinese-queues

- Joshua S. Yang, The Anti-Chinese Cubic Air Ordinance, Am J Public Health. 2009 March; 99(3): 440.

- Michael R. Godley, The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History, China Heritage Quarterly. China Heritage Project, The Australian National University. September 2011, Accessed December 3, 2022, http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=027_queue.inc&issue=027

- Patrick Joseph Healy, A Statement for Non-exclusion. 1905, pp. 245–251, Accessed December 3, 2022, https://archive.org/details/astatementforno01nggoog/page/n245/mode/2up

- 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Primary Documents in American History, Accessed December 3, 2022, https://guides.loc.gov/14th-amendment