Author: William Tang

Translator: Ella Wu

The legendary Sun Yun, who is now known as Cecilia Chiang, was given her English name by a professor while studying at Fu Jen Catholic University in Peiping.

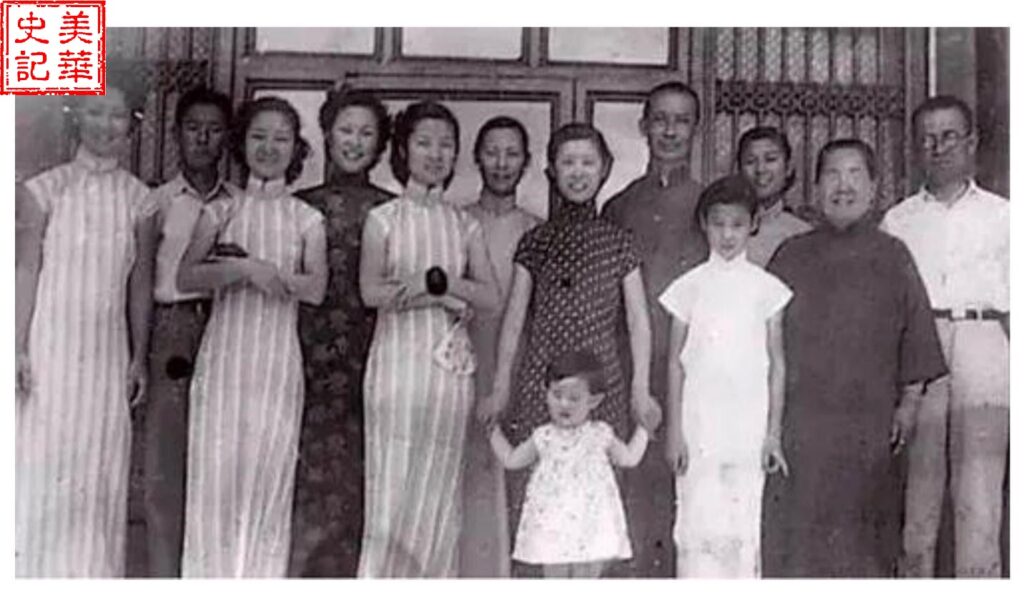

Sun Yun was born on September 18th, 1920 in Jiangsu, China. Her grandfather was the director of the Sino-French Railway, and her father Sun Longguang studied in France as a railway engineer, and later became the director of the Sino-French Railway Materials Factory. Sun Yun’s mother Sun Xue Yunhui led an enriched life and loved to cook. Sun’s parents gave birth to eleven children, two boys and nine girls. She was the seventh daughter of the Sun family.

Picture 1, The Sun Family

The Sun family was very well-off, owning several factories. When Sun Yun was five years old, her family moved to Peiping and lived in the equivalent of a palace with 7 courtyards and 52 rooms.

Her parents adored food. As a testament to this fact, they hired two chefs to cook northern Chinese and southern Chinese dishes for them. During their meals, Mr. and Mrs. Sun would talk about the methods of preparation of the dish. Under this influence, Sun Yun’s interest in food grew by the day. Even though the children were not allowed in the kitchen, Sun Yun familiarized herself with the stories and methods of these dishes and in turn developed a passionate appreciation for cooking.

In 1939, the Japanese army began their occupation of Peiping, and the fate of the Sun family was suddenly derailed by danger.

In 1942, as soon as Sun Yun finished university, she began a journey on foot with her fifth sister to Chongqing, the wartime capital of the Nationalist government. The journey was as precarious as it was arduous. All of her belongings were robbed by Japanese soldiers. She lived on the few gold coins sewn into her clothes. When passing through Henan, she witnessed people living in even worse conditions than herself. They cooked vegetables only with water, no oil. After more than five months and two thousand kilometers of travel, the sisters finally arrived in Chongqing where they stayed with relatives.

Sun Yun went to primary school and high school in Peiping. She was educated at Fu Jen Catholic University where she became fluent in Mandarin and English. After arriving in Chongqing, she found a job teaching Mandarin at the American embassy and the Soviet embassy. During the war against the Japanese, she also served as an espionage officer for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), collecting enemy intelligence and contributing to the International Anti-Fascist War.

In Chongqing, she also met an old acquaintance, Jiang Liang, who was a professor of economics at Fu Jen Catholic University and an executive of a tobacco company. The two eventually became husband and wife, and Sun Yun adopted her husband’s surname Chiang (Jiang). After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, Cecilia Chiang and her husband Chiang Liang moved to Shanghai. They had a son and daughter, Philip and May.

In 1949, Jiang Liang was appointed as the Commercial Counselor of the Embassy of the Republic of China in Japan. The couple flew to Tokyo with their daughter on the eve of the regime change in mainland China. Their son followed Cecilia Chiang’s sister to Taipei. The family was reunited more than a year later.

Chiang was not used to the Japanese food in Tokyo and so cooperated with others to open a Chinese restaurant Forbidden City.

Picture 2, Young Cecilia Chiang

In 1959 she received a telegram from Sun Sun, the sixth sister in the Sun family, who had been living in the United States for only a year when her husband William Hoy (a reporter for the U.S. military during World War II and one of the three founders of the Sino-American English News in San Francisco Chinatown) died of liver disease. When Cecilia Chiang learned the devastating news, she decided to go to the United States to be by her sister’s side.

In 1960, Chiang arrived in San Francisco by ship.

Once in San Francisco, Chiang was, to say the least, displeased by the Americanized Chinese food, mainly Cantonese food, served there. If not egg foo young, it was chop suey (shredded pork and chicken stir-fried quickly with vegetables). The tastes were raucously sweet and sour to meet Americans’ taste. She could in no way eat any of the food.

At the time, Chinese restaurants were plain, dishes were simple, and prices were cheap, thus being considered by Americans as the food for the poor.

One day while roaming the streets of Chinatown, Chiang ran into two friends she met during her time in Japan. They wanted to rent a shop at 2209 Polk Street to start a Chinese restaurant. They asked Chiang to help negotiate with the landlord because the latter spoke English better than they. Chiang was eager to help and even impulsively wrote a check for $10,000 as a down payment on the shop. Unexpectedly at the last minute, the two friends changed their minds and opted out of their plans to start the restaurant. Because the landlord would not refund Chiang’s $10,000, she decided to grit her teeth and start this restaurant on her own, thus committing the rest of her life to promoting authentic Chinese food in the States.

She wanted to juxtapose Western service with authentic Chinese food in the construction of her restaurant as a display of Chinese culture.

She said, “Since the food in Chinatown’s Chinese restaurants is so bad, I’m going to let Americans know what real Chinese food is!”

In the start-up of her restaurant, though, Chiang faced endless struggles and difficulties ranging from lack of funds and lack of helping hands to racial discrimination, sexism, and the struggle of the restaurant industry which was dominated by Cantonese speakers, unlike herself who spoke Mandarin. None of this deterred Chiang though; she was determined to accomplish her goal.

She devoted enormous amounts of time towards the construction and decoration of the shop in order to highlight the charm of Chinese culture. She also began to record all of the two hundred recipes that she learned ever since she was a child. Through advertisements in newspapers and magazines, she employed a Shandong couple skilled in northern cuisine and wheaten food. She herself purchased ingredients and coordinated internal and external affairs of the restaurant.

In 1962, Cecilia Chiang’s The Mandarin Chinese restaurant finally opened at 2209 Polk Street with the occupation of 65 seats.

Picture 3, Chiang had been running The Mandarin since 1962

Business was not very good in the first two years. Owing to limited financial resources and lack of the first two years. Chiang had to do everything on her own; it was truly a one-woman show. She greeted guests, took orders, and even enlightened customers on the cultural connotations of each dish in Mandarin and English. During the day, she would wear a silk cheongsam with elegant jewelry, and at night she would put on her overalls and sweep the floors and clean the bathrooms.

She launched the most popular Chinese traditional dishes in her menu–Peking duck, braised pork, braised lion head, pot stickers, fish-flavored pork shreds and so on.

At the time, many Chinese food seasonings could not be bought locally, so she had to trek to Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan to buy them.

Gradually, Chinese and Americans started filling up the seats regularly.

One evening, Herb Caen, a columnist for the prestigious San Francisco Chronicle, dined at The Mandarin. Afterwards, he wrote an article titled “A Newly Founded Restaurant Serving Real Chinese Food,” in which he said the “little restaurant” served “some of the best Chinese food on the Pacific East Coast.” The Mandarin became famous overnight and swept the whole city off its feet. People lined the streets to get a seat at The Mandarin when it was full.

In 1968, Chiang opened another branch of restaurant in Ghirardelli Square with 300 seats and paintings by Zhang Daqian and Qi Baishi on the walls.

Visiting foreign countries’ leaders like to select this restaurant to entertain guests.

Important people from all over came to get a taste of The Mandarin. Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, King of Denmark, tenor Pavarotti, Hollywood’s Schwarzenegger, Chinese playwright Li Jinyang, the Beatles and other politicians and celebrities went to dine there.

The Mandarin received many honors in the food industry. Honored by Holiday Magazine for 32 consecutive years, it was the only Chinese restaurant that had been awarded the Five-Star Mobile Award for three consecutive years, and won the Ivy Award sponsored by the American restaurant industry. Playboy magazine has featured The Mandarin as one of the best Chinese restaurants.

In 1975, Chiang opened a branch in Beverly Hills, California. Kung Pao Chicken, Stewed Beef, Fish-flavored Eggplant, Beggar Chicken, Twice-cooked Pork, Mugwort Pork, Fried Banana and other dishes became popular.

Picture 4, Delicious set of dishes prepared under Chiang’s guidance

The talent for impeccable Chinese food ran in the family, apparently. Chiang’s son, Philip Chiang, also became a well-known American restaurant owner. In 1989, he bought his mother’s Beverly Hills branch of The Mandarin. In 1993, Philip Chiang and Paul Fleming co-founded P. F. Chang’s China Bistro, an American-style Chinese restaurant, which now has more than 200 chain restaurants in the United States alone.

When Cecilia Chiang was 71 years old in 1991, she sold the first Mandarin and retired. In 2006, the Mandarin shut down at last. The first Chinese restaurant in the history of the United States specializing in authentic Chinese food ended its glorious history of 44 years.

In 2007, the San Francisco Chronicle published a profile on her life’s work, saying that her restaurant “defined high-end Chinese food, introducing customers to Sichuan dishes such as Kung Pao Chicken and Twice-cooked Pork, while masterfully using lettuce pigeon floss and camphor tea duck and beggar chicken, stuffed with mushrooms, water chestnuts and ham and baked in soil, which redefined cooking methods.”

Chiang became a consultant for The Mandarin in the Girardelli Plaza, where she worked diligently into her 90s.

In 2013, the restaurant pioneer received the James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, known as the Oscars of the restaurant industry. At the award ceremony, she wore a red cheongsam and a set of jade jewelry, elegantly representing her culture. She said: “All my perseverance and dedication are to let the world know that the best food is Chinese food, and if it’s bad it’s because it’s not authentic Chinese food.”

Picture 5, Jiang Sunyun’s speech at the James Beard Foundation Awards Ceremony

Director Wang Ying made a documentary about Chiang called Soul of a Banquet, which was released in 2014. In 2016, the KPBS channel of San Diego Public Broadcasting Company (PBS) aired a six-episode series “The Kitchen Wisdom of Cecilia Chiang,” which recounted her extraordinary life.

In 2016, The Mandarin was listed as one of the “Ten Restaurants That Changed America” by restaurant scholar Paul Freedman, introducing Sichuan cuisine and North China food other than chop suey, fried noodles, etc. to the United States. Chiang is known as the “Child of Chinese Cuisine”, as instrumental as Julia Child, the culinary master who introduced French cuisine to the United States.

Chiang published her memoir The Mandarin Way, co-authored with Allan Carr, in 1974. Her personal biography, co-authored with Lisa Weiss, was published in 2007. It’s titled The Seventh Daughter: My Culinary Journey from Beijing to San Francisco.

At 3:40 a.m. on October 28, 2020, Cecilia Chiang passed away in her home at Pacific Heights, San Francisco at the age of 100. The news was front page news on CNN that morning. Since then, the “Queen of Chinese Food” earned her place in the top ranks of Chinese-American history.

James Ho, a good friend of Chiang’s, and former Vice Mayor of San Francisco said that she was a woman who had seen a lot, done a lot, dared to criticize, and did it all with warmth and sincerity.

ABSTRACT

Cecilia Chiang, whose original name was Sun Yun, was born in Wuxi, Jiangsu, China on September 18, 1920. Her father, Sun Long Guang, was a railroad engineer who was educated in France and her mother, Sun Shueh Yun Hui, was from a wealthy family that owned textile mills and flour mills.

When she was a child, her family moved to Peking(Beijing), where she was raised in a 52-room, converted Ming-era mansion that occupied an entire block. She enjoyed elaborate formal meals prepared by the family’s two chefs, though the children were not allowed to cook or go into the kitchen.

She escaped with a sister from the Japanese occupation of Peking by walking for nearly six months to Chongqing, where they settled with a relative. During her time there, she worked as a Mandarin teacher for the American and Soviet embassies. During the war time she was a spy for America’s Office of Strategic Services.

She met Chiang Liang in Chongqing, a former economics professor at Fu Jen Catholic University and they got married. They had two children, a boy and a girl.

In 1949 Cecilia, her husband and their daughter went to Tokyo, Japan.

In 1960 Cecilia came to the United States and later she started her Chinese restaurant business. She successfully brought authentic Chinese food to America.

Cecilia Chiang passed away on October 28, 2020 at the age of 100.

References:

- Belinda Leong. Cecilia Chiang, in Her Own Words. Eater, original on July 20, 2018, Retrieved Oct 28, 2020. https://www.eater.com/2018/7/20/17419118/cecilia-chiang-interview-profile-belinda-leong

- Bauer, Michael (May 25, 2011). “At the Mandarin, Cecilia Chiang changed Chinese food”. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Cecilia Chiang, Lisa Weiss. The Seventh Daughter: My Culinary Journey from Beijing to San Francisco.

- Hilarie Gottlieb. The Journey From Shanghai to Gold Mountain.

- Chang Chiu Chen. Cecilia Chiang: Godmother of Chinese American Cuisine (Oral history of Chinese American Women Series).