Author: William Tang

(Vice President of Arizona Chinese History Association)

Translator: Joyce Zhao

ABSTRACT

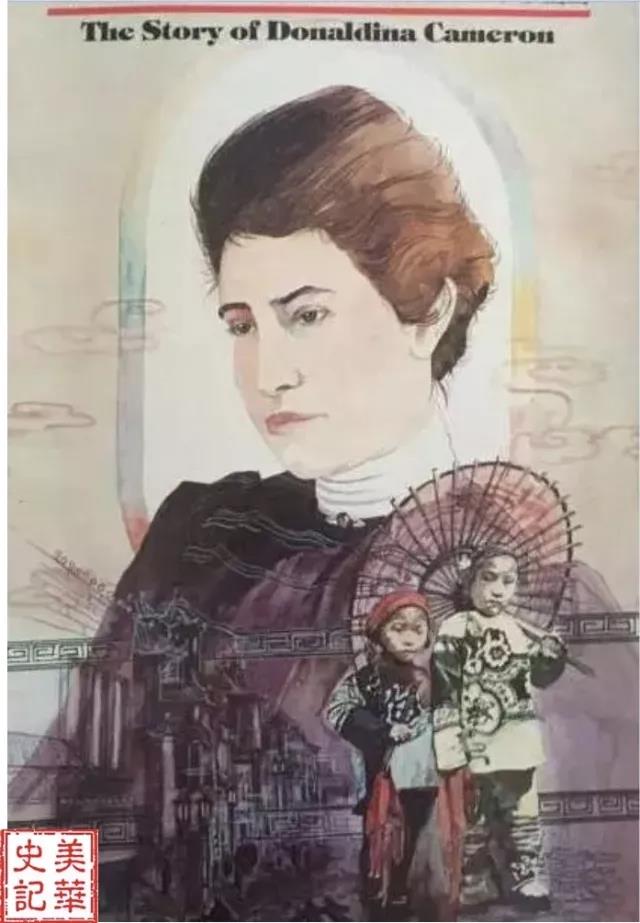

Donaldina Cameron (July 26, 1869-January 4, 1968) was a Presbyterian missionary in San Francisco’s Chinatown, who rescued more than 3,000 Chinese immigrant girls and women from indentured servitude. She was known as the “Angry Angel of Chinatown.”

~~~

Chinatown, also known as the street of Tang people, can be found all over the world. Among them, Chinatown in San Francisco, USA, is the largest, with the longest history and the strongest Chinese flavor. The shops are lined up row by row, the customers are constantly flowing, and the signs are all in Chinese.

San Francisco’s Chinatown, also known as Chinese port, dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, China was suffering from internal and external troubles, and the people were unable to make a living. After the discovery of gold mines in California, the U.S. government recruited cheap labor in China. Their first stop in the United States was San Francisco. Since its formation in the 1840s, San Francisco’s Chinatown has been playing an important role in the history and culture of the United States and even the entire North American Chinese immigrant community. It holds many stories, telling many legends.

San Francisco Chinatown

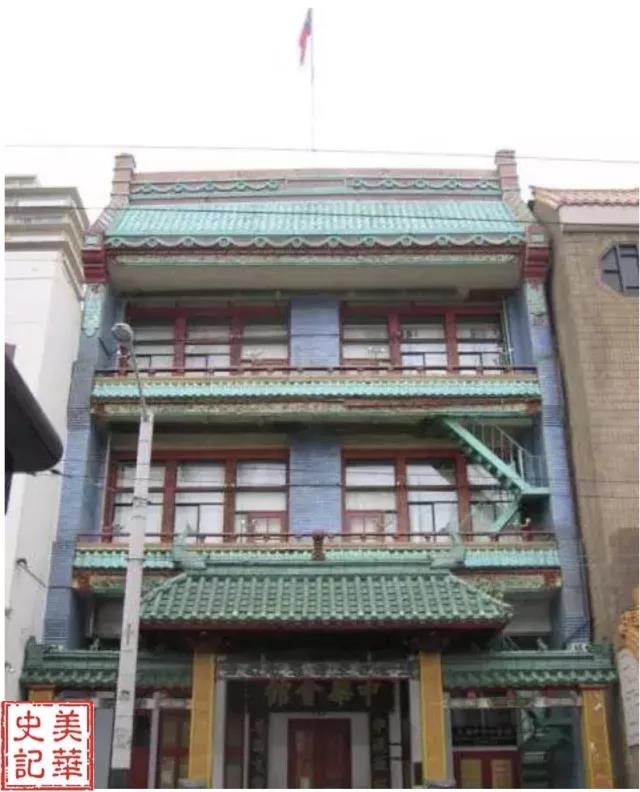

San Francisco’s 920 Sacramento Street is a grand five-story red brick building with a basement below. This building is called Cameron House, which is called Jin Meilun House in Chinese. In the early years, it was the Presbyterian Mission House — a charity organization that supported Chinese women. It was built in 1874 and started its business in 1895, hosted by the missionary Donaldina Cameron (1869-1968, Chinese name Jin Meilun). This building was destroyed by the San Francisco earthquake and fire in 1906, but it was rebuilt in the same place in 1907. It still stands there today.

Cameron in Chinese style clothing

Cameron was born in Cydevale, New Zealand on July 26, 1869. When she was two years old, she moved to San Francisco with her parents and grew up among the wealthy. Young Cameron did not yet understand immigrant groups. Once, Mary P.D. Browne, a friend of her parents, took Donaldina Cameron to the Presbyterian Mission House and let her witness the world around her with her own eyes. It was the first time for little Cameron to see so many Asian girls who were rescued. Most of them were Chinese, but there were also a few Japanese and Koreans. They ate and lived inside, read, and did needlework, forming a small society of only women. This incident left a deep impression on little Cameron.

When Cameron was 22 years old, she worked in this mission house as a sewing teacher. At the age of 25, she became the director of the mission house. From 1895 to 1934 when she retired, in these forty years, she rescued about 3,000 Chinese women who had become slaves and prostitutes and placed them in the Presbyterian Mission House. She taught them English, educated them in housekeeping and life skills, preached to them, made them believe in Christianity, and finally marry a Christian man. Ms. Cameron also won the title of Angel of Chinatown.

Cameron and the Chinese girls

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first immigration law issued by the U.S. federal government. The bill stipulated that Chinese men were not allowed to leave the United States; once they left the United States, they were not allowed to return. The decree also prohibited single Chinese women from entering the United States, with the exception of having a marriage relationship with a man in the United States. This discriminatory bill was not cancelled until 1943, after China and the United States became allies for the resistance against Japan.

If the U.S. government had policies, then the Chinese had countermeasures. This resulted in the prevalence of fake marriages, and a large number of women from the southeastern coast of China entered the United States, manipulated by human trafficking groups. Some less fortunate families, because of their patriarchal ideals and the flowery persuasion of human traffickers, thought that the United States was full of gold. The parents thus rashly handed over their daughters to the human traffickers to send their daughters to the United States. This phenomenon was called the Yellow Slave Trade.

Cameron and Chinese Women

These Chinese women were called “Mui Tsais”. After they arrived in the United States, they found that no man wanted to marry them right away, and there were not many kind hearted people willing to take them in. So the Chinese mafia, through promises of helping them pay the large amount of travel expenses to arrive in America, sold them to wealthy families as slaves. Those that had prettier appearances were sold into brothels as sex slaves. The money that they earned went into advance expenses for the human trafficking groups, which of course had high profit sharing.

Today, the Cameron House also displays a deed for the sale of a Chinese woman named “Xinjin”, written with a brush in the twelfth year of Guangxu in the Qing Dynasty (1886). It says “voluntarily became a prostitute”, the price is listed as 1,205 yuan, and the contract states four and a half years. It also says “silver does not count the profit, the person does not count the work”. If sick, the woman would be sent back to China. If pregnant, the contract would be extended by one year.

Church members of the Presbyterian Mission and Chinese women who received shelter

The girls who waited on the master in a rich man’s house, due to the fact that they were bought with money, could not escape the fate of abuse and domestic violence. These women who were thrown into the fiery pit had an extremely miserable life, and usually died of torture within five years. Therefore, the number of Chinese girls who escaped to seek social assistance increased by the day.

Of course, the San Francisco municipality knew about Chinatown’s trading of “Mui Tsais”, and the Six Companies (Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) also wanted to intervene. However, in the face of the powerful mafia, they all felt acutely powerless.

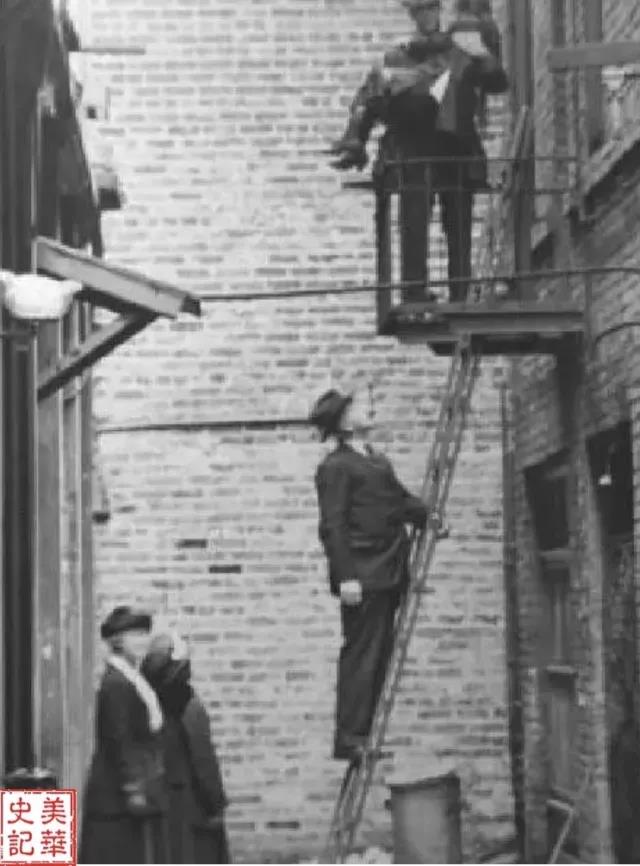

Rescuing the imprisoned Chinese girl

Cameron took over the Presbyterian Mission House in these circumstances. The tragic fate of the Chinese girls shocked her. She was determined to change their methods of help and transformed the Presbyterian Mission House into a home for Chinese women, which was also a shelter for Chinese women. She gave herself a Chinese name, Jin Meilun. The girls in the shelter affectionately called her “Lo Mo”, while human traffickers and gangsters called her “Fahn Quai”.

The Chinese women’s shelter home was often harassed by human traffickers. In addition to turning to the police and the church for help, Cameron also opened a secret passage to the outside of the refuge. Kwong Huixian, the current director of the social service department of Cameron Hall, said: “Human traffickers sometimes came here suddenly to find those women. Cameron helped the women use this passage to escape.”

San Francisco Six Companies

Cameron’s righteous actions soon produced a strong response in Chinatown, and there was a steady stream of Chinese girls seeking help. Some people also handed out a secret note in the middle of the night, saying where there were imprisoned Chinese girls, where there were girls trapped in adultery who needed help, etc. As soon as she got word, Cameron would go out to search for and rescue the girls.

Cameron had a tough face and an atmosphere of righteousness. She was impartial, not afraid of violence, and most people respected her. She abhorred evil, and English newspapers called her “the angry angel of Chinatown”. McLeod, the former administrative director of Cameron House, said: “Cameron is called an angry angel because she is indignant at what happened to Chinese women. Women are treated as goods by their compatriots and sold here to make money. They lost all of their dignity and human rights.”

The influential men at the Six Companies in San Francisco in the early years

Chinese women who were rescued had to reside in the Presbyterian Mission House and could not go out alone. If they wanted to go out, they had to be accompanied by someone. The mission house preached to them, taught them to read the Bible, and made them believe in Christianity. At that time, it was the custom of Chinese society that girls rarely went to school. So after they arrived at the mission house, they had to take a strictly laid out English course and learn the various kinds of work done by American housewives.

After a considerable period of training — only after they married a Christian man approved by Cameron — these Chinese women could leave the missionary school and start their own families.

In 1942, the Presbyterian Mission House, also known as the Chinese women’s shelter, was officially renamed Cameron House to commemorate her dedication over the decades.

Mildred Martin wrote Chinatown’s Angry Angel — The Story of Donaldina Cameron

Cameron died on July 26, 1968 in Palo Alto, near San Francisco, at the age of 98. She rescued and sheltered about 3,000 Chinese women throughout her life, taught them English and life skills, and helped them form families in the United States, but she herself was unmarried for life.

Notes:

1. Chinatown’s Angry Angel by Mildred Crowl Martin

2. Cameron House