Author: Fan Jiao

Editor: Michelle X. Li

ABSTRACT

The year of 1982 marked the awakening of the Chinese American Civil Rights Movements. On June 23, 1982, 陈果仁 (Vincent Chin) was beaten to death by two white men in Detroit. The lenient sentence led to an outcry from Asian-American community. Some six hundred miles away in New York City, on November 19, tens of thousands of Chinese New Yorkers marched in the streets of NYC protesting the city’s proposal of building a new prison in the vicinity of Chinatown. Over the next forty years, as the number of jails increased, the political participation of Chinese New Yorkers increased as well. After many years of efforts, Chinese New Yorkers began to win more and more elected city seats.

On a foggy Friday afternoon, November 19, 1982, around 12,000 people poured into the streets of downtown New York City, passing through the Foley Square courthouse to reach City Hall to protest a plan to build a prison near Chinatown. The protest was orderly and peaceful, and the marchers’ spirit was high, accompanied with dragon-dancing and loud drumming. Because of the high turnout of protesters and marchers, the police had to temporarily block the traffic into the Brooklyn Bridge [1].

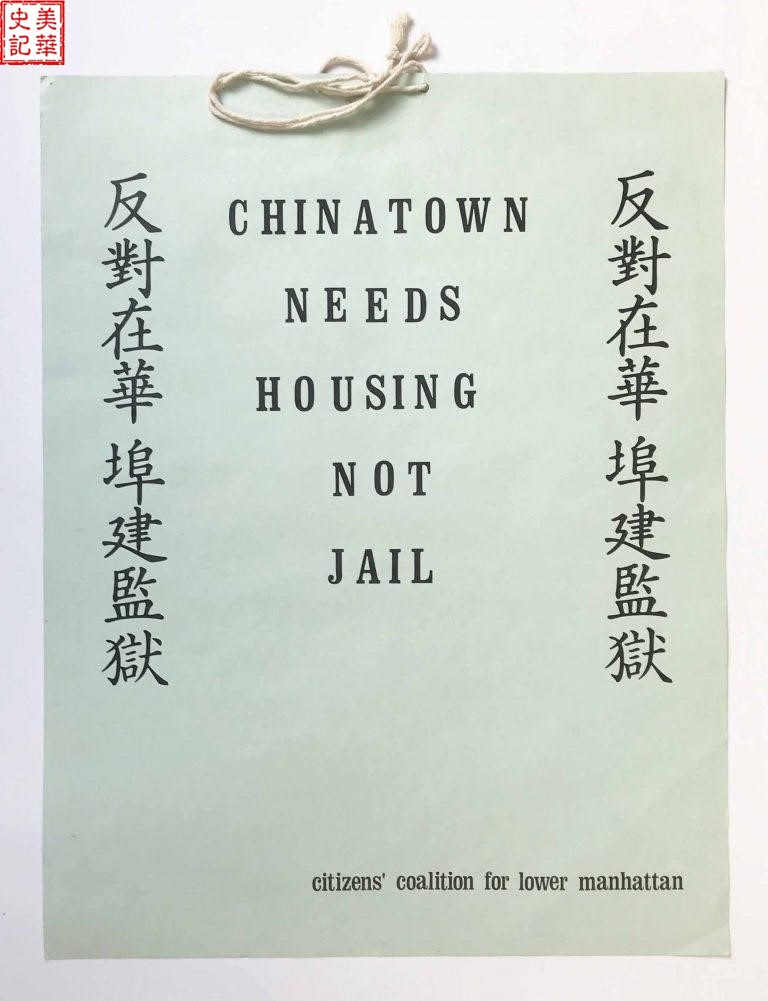

[Fig. 1] Veterans protest against the construction of a prison in Chinatown. Photo provided by Corky Lee (李杨国)

[Fig. 2] Demonstrators’ signs. Source

At the city hall, the city board started discussion of the prison plan at 9 p.m, and continued late into the night. Then, Senate Minority Leader Manfred Orenstein of Manhattan and his supporter, City Police Commissioner Benjamin Ward, raised their objections to the plan. The protesters who packed the board room applauded those who opposed the plan.

The prison was proposed to be built on the streets of Centre, Baxter, Walker and White. Residents and community leaders argued that there were already two state prisons near the new proposed prison. Including the Manhattan Prison in New York, the total number of prisons in the area far exceeded the proportion of the local population and would harm the environment and the lives of the people in the neighborhood.

Hours after the protesters returned home, in the early morning of Nov. 20, 1982, he City Assessment Commission voted to delay the construction of the $101 million prison project in Chinatown, a partial victory for the protesters

Prison reform in the 1980s

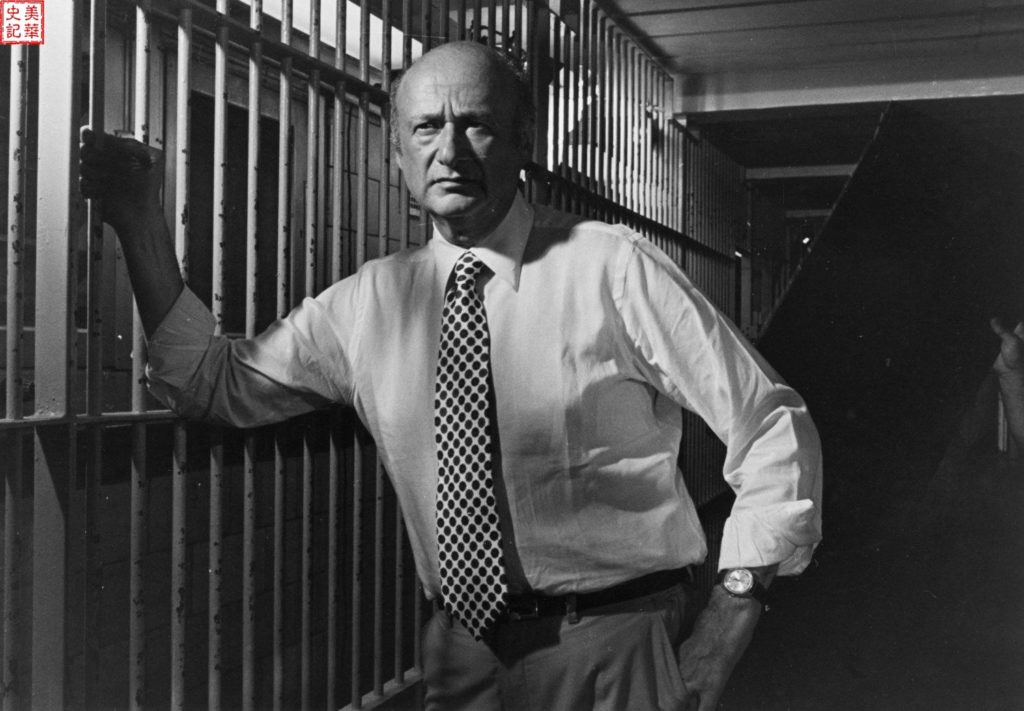

In the fall of 1982, by a court order, New York City closed one of several prisons on Rikers’ Island, the Men’s Detention Center. The city was also planning to close the Spofford Youth Detention Center in the Bronx. In order to accommodate all these new prisoners, Mayor Ed Koch’s government proposed the construction of a new prison in the Manhattan Detention Center near Chinatown (north tower, completed in 1990), adjacent to the older “grave” prison (south tower, reopened in 1983). The facility could accommodate 898 prisoners. At that time, there were already two federal prisons and city detention centers near Chinatown [2].

[Fig. 3] Mayor Ed Koch at Rikers Island Prison. Source

[Fig. 4] Rikers Island Prison. The 413-acre prison contains 11 prison buildings and houses 7,000 inmates. Source

[Fig. 5] The North Tower of the Manhattan Detention Center, built in 1990. Source

When Mayor Koch proposed the construction of the North Tower, the mayor’s office didn’t discuss his plans with the local Chinese community. Therefore, once the news broke, large-scale protests emerged in Chinatown.

The “prison proposal” of the 1980s inspired an activism movement among Chinese New Yorkers . Although the movement did not stop the construction of the nine-story North Tower, their efforts did lead to some compromises from the local government: New York City agreed to build an 88-story high-rise residential area with underground commercial space on the property next to the prison in the Chinatown area.

Inspired Chinese New Yorkers’ Civil Right Movement

Although Asian Americans have resided in New York since its establishment,New York never elected Asian Americans to city councils or city offices before 2000. Mayor Ed Koch dismissed a massive protest in Chinatown in 1983 against the proposed prison. He pointed to the fact that “if you don’t vote, you don’t count.“

Behind Koch’s infamous discounting was the political indifference of Asian New Yorkers. Indeed, at the time, although many Asian-Americans had been naturalized and registered to vote, only 41% voted in the election prior to 2010. Coupled with the 1882 U.S. “Chinese Exclusion Act”, it slowed the development of the Asian-American community, prevented Asian immigrants from becoming citizens, and removed them from New York politics. Although the Chinese community strongly opposed the proposed prison expansion in the 1980s, “If you don’t vote, you don’t count” was a commonly heard phrase in City Hall back then.

The incident became the driving force behind the Chinese New Yorkers’ civil rights movement. Many local leaders today, including Margaret Chin, took part in the protests and have been actively involved in politics ever since. In the 1990s, New York City’s Asian population grew by 54%, and one in ten New Yorkers was Asian-American. According to the most recent census in 2012, 6.3% of New York City was Chinese, with about half a million people [4].

Margaret grew up in NYC Chinatown, and graduated from Bronx High School of Science and the New York City Collegewith a degree in education . She has been a member of several public service groups and organizations. In 1974, she was a founding member of the Asian American Equality Organization; the organization works to “empower Asian Americans and others in need“. She also served as chairman of the board from 1982 to 1986. After 16 years of hard work, Chin won the election for the position of first district councilor of the city council in 2009 [3].

John C. Liu was also an activist at the time. In 2001, he was elected to the New York City Council, becoming the first Asian-American member of Congress. From 2002 to 2009, he represented District 20 in Northeast Queens as a member of the New York City Council. Later, he was elected to the New York State Senate in the 11th District of Northeast Queens. He also served as the 43rd New York City Auditor General from 2010 to 2013 and was a candidate in the 2013 New York City mayoral election [5].

[Fig. 6] City Councilman Margaret Chin made a speech at City Hall. Source

Prison Reform Plan of 2018

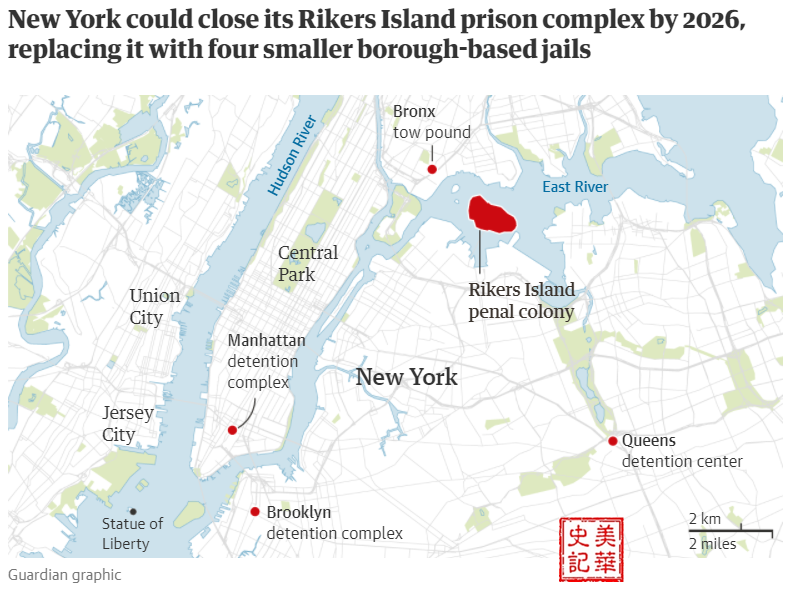

In 2018, to close New York City’s most notorious prison, Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed a four-district prison plan, replacing Rikers Island with four smaller prisons in each district except Staten Island, at a cost of $8.7 billion, with the aim of halving the city’s prison population by 2026.

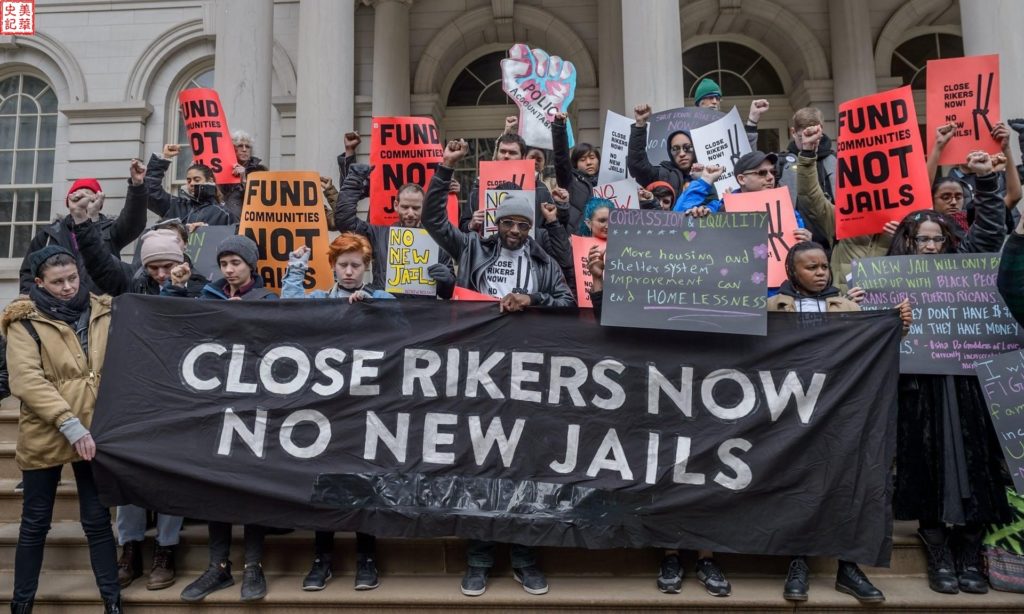

Residents were concerned about the transparency, health and political neglect of the plan. Carlin Chan(陳齡), an activist and campaigner, said to the reporters that the biggest problem was the health consequences of dismantling old prisons and building four new ones [6]. Secondly, the participants in these planned meetings were limited to certain community organizations only, while the majority of the community members were not allowed to participate. In addition, the city by and large ignored the views of the community and moved projects forward without consulting the people who were most affected. The New York City government has refused to recognize and consider the views of Chinatown residents for decades; the controversial discussion about the Chinatown prison in 1982 was just one example of this ongoing issue.

Studies have shown that the demolition of the old prison and the construction of the new one would indeed cause many health problems. A 2018 testimony from the Center for Asian American Health Research at New York University said that the project could seriously affect the health of older people and could even be fatal. The center also wrote that moving elderly people could accelerate the aging of residents and have a negative impact on their mental health. The health crisis caused by the Chinatown Prison plan in the area could continue for a long time after the facility was completed.

[Fig. 7] New York government plans for 2018. Source

[Fig. 8] Members of the community from No New Jails demonstrate at the rally Source

.

[Fig. 9] Carlin Chan and his supporters. source

2020’s Judge Decision

On Monday, September 20, 2020, State Supreme Court Judge John Kelley ruled in favor of Neighbors United Below Canal (NUBC) and other community groups that sued over the Chinatown Prison plan. In the ruling, Kelley based the decision on complaints that the City Council ignored correct procedures and failed to get impact studies and approvals for a plan that was still being formulated. The original height of the proposed jail to replace the Manhattan Detention Complex was about 50 stories, but the city reduced the planned height to 29 floors [7].

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan was to replace Rikers Island with a network of four smaller prisons. The New York State High Court’s decision was a decisive blow to the plan. The mayor’s plan for 2018 was to build four new prisons near courts in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. Less than a year later, State Supreme Court justices effectively canceled Manhattan’s prison construction, which is likely to end the entire program and put a decisive negative score on the mayor’s record.

Additionally, the ruling, along with two other lawsuits against the Bronx and Queens complexes, coupled with budget shortfalls related to COVID-19, has delayed the Rikers prison demolition plan as well, which has had a significant impact on the mayor’s commitment to closing Rikers Island.

In short, from the construction of a new prison in Manhattan in 1982 to the new prison replacement plan in 2018, Chinese New Yorkers continue to unite other community members and charter their own course on the path of social justice and equal rights, which deserves to be studied and appreciated by Chinese Americans across the United States.

Annotations:

- The Protest March in Chinatown https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/19/business/action-on-chinatown-jail-put-off-after-protest.html

- Chinatown’s negative reaction to the prison plan https://documentedny.com/2018/09/25/what-does-chinatown-hate-about-the-plan-to-close-rikers-almost-everything/

- City Councilman Margaret Chin https://www.nychinaren.com/company/task_view/id_15678/% E9%99%88% E5% 80% A9% E9% 9B% AF .html

- The growth of Chinese population in New York City https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City#Race_and_ethnicity

- NY State Senator John Liu https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/personality/personality/john-liu-iron-man.html

- Community Activist Carlin Chan https://www.boweryboogie.com/2019/01/the-mayor-can-sell-his-jail-plan-elsewhere-chinatowns-not-buying-op-ed/

- The judge revoked the new prison permit https://ny.curbed.com/2020/9/23/21451653/rikers-island-de-blasio-chinatown-jail-lawsuit